Reader’s Digest used to have a feature called “My Most Unforgettable Character.” When Sonny Bono died, Cher delivered the eulogy and said that Sonny was her nominee for that role in her life.

My choice is Jerome Laizure. I knew him for only four years in the mid-eighties. We wrote or called only sporadically in the years after I moved away from Oklahoma, but he was always on my mind.

He ran the printing operation of the Oklahoma Daily during my years teaching journalism at the University of Oklahoma. His office was on the other side of the building, and we’d often hang out in the no-man’s-land in between, in the journalism school’s main lobby.

Jerry was fearless. The man had no filter, and I loved him for that.

“Hey, Jerry,” I’d say. “Ed Carter wants to talk to you.”

“Well, he can just kiss my cracked ass,” Jerry’d say in that deep-gut twang.

Didn’t matter who was standing within earshot. Jerry was Jerry and he said whatever was on his mind. He never worried about what people thought. He was ill-disposed to kiss any ass on the planet.

He was one of the strongest, most ethical people I ever knew.

I realize that this kiss-my-cracked-ass thing doesn’t endear him to you, but context is everything. You had to be there. He was a Picasso of profanity. I should solicit our shared friends for more examples of his brilliance with blue language, which put him in the same rarefied and profane air as Hunter S. Thompson. But even if I compiled a three-volume catalog of his swears, it would detract from what I want to say.

Rough on the surface, he was unsentimentally sentimental. He could go zero-to-60 with curses in record time. Above and beyond these theatrical qualities, he was an intelligent, sincere and wise dude. He shepherded scores of students into careers as journalists and was, during a difficult time in my life, my conscience and my great friend.

He left the university and started a weekly newspaper in a nearby small town and later went on to a distinguished career in photojournalism. I was gone by then, but could still admire his work. If anything happened in Oklahoma — and lots of things did that made the national magazines — look at the photo credit. Good chance it was Jerry’s work.

He and I were about the same age and so I have to say that when he died some years back, he was much too young. Much.

He’d been dealing with a number of health issues and in our infrequent communiqués, he’d tell me of all the things he could no longer do.

His death was a shock to me, but perhaps not so to those closest to him. He was not tall, but still managed to be a towering figure, larger than life. I didn’t understand how fragile he was.

He was deeply loved. When he died, his Facebook page turned into a tribute, a virtual temple of bouquets left by those whose lives he touched. In the days after his death, I’d look at his page every few hours, to read the new bouquets left by friends. The family posted pictures of the funeral, and his children wrote about how fortunate they were to have him as a father.

A week or so after his death, I checked his Facebook page on a Sunday night. Peggy, his wife — now widow, I suppose — had posted: “Damn it, Jerry. Where’d you leave the remote?”

Man, they loved each other, and they set a high bar. We should all be so lucky to have a relationship like theirs.

Back in the old days, back in the eighties when our children were small, I used to love to hear Jerry talk about his kids. “I got three,” he’d say. “One of each: a boy, a girl, and Jackson.”

Maybe that’s a subliminal reason I have a son named Jackson. (I’d been pushing for Elvis, and the family history is murky on how he became Jackson, but Jerry’s son might be the reason I didn’t put up a fuss when the name was suggested.)

Jerry’s death shook me as much as a death in my biological family. There were few pre-cancer times when I had such a sense of fragility.

I hadn’t seen him in years, but he was there, in my head, and at the other end of the keyboard when we’d exchange messages.

I’d moved away to Florida and always wanted him to come visit, telling him to bring the family, to stay at my house, and have a cheap-ass trip to Disney World. He said he’d come, but it never happened. He was always working.

I wanted to take myself back to the old days, when Jerry would saunter across the lobby to my office. I was doing a term as assistant director of the school, stuck in an windowless box in the administrative suite. I’d hear the outer door open, but couldn’t see who was there. Then I’d hear him gently growl at the receptionist.

“Is that useless dipshit in?”

He was from Bartlesville and had an oilfield twang. The receptionist giggle would follow, no doubt accompanied by her finger pointing toward my office.

Then he’d darken my door: “Are we going to fuckin’ eat or what?”

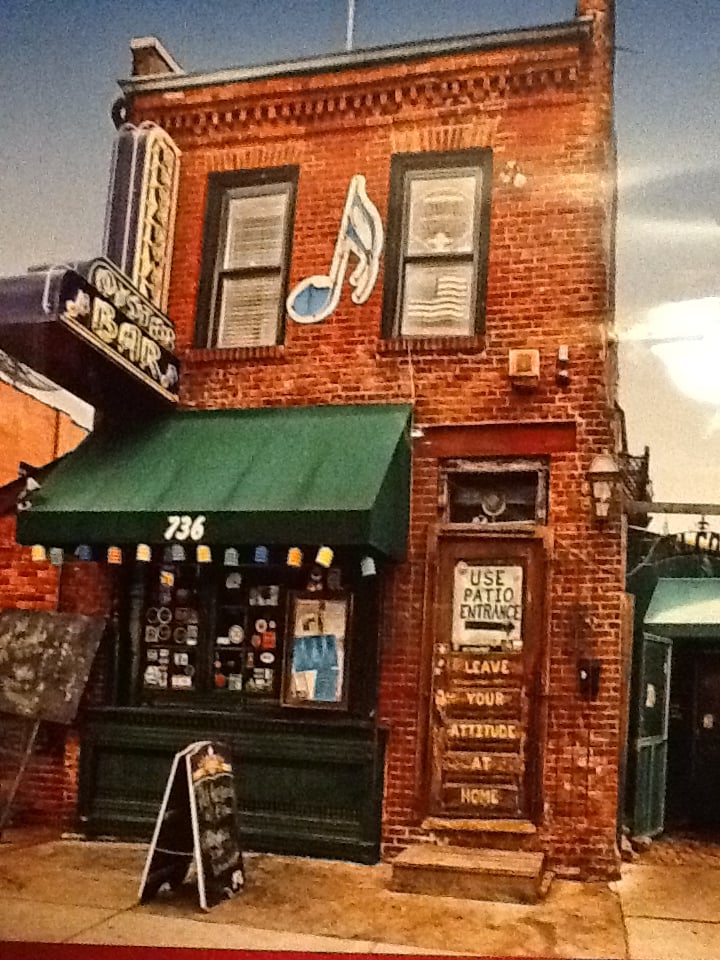

So we’d amble across the street — Jerry never went anywhere with dispatch — to our local burger joint, the appropriately named Mister Bill’s.

We had the menu memorized and each day had a different special — the California Burger, the Grandma Burger, the Salsa Burger and so on. We ordered in kind and, now and then, committed that work-day sin of a lunch-time beer.

Those long lunches and conversations were my graduate education in human studies. Jerry was so much smarter than me when it came to understanding our fellow beings and their psychology. I wrote about people and what they did, but Jerry seemed to know what people would do before they did it, before even they knew what they would do.

Those afternoons at Mister Bill’s were my Paris in the Twenties or my Algonquin roundtable, but with a limited cast of characters.

Jerry and I never tired of talking or ran out of subjects to consider, or world problems we felt called upon to solve. Jerry might be the most genuine person I’ve known. He had a bullshit detector finely tuned by a Swiss artisan and he used it on others and himself. He was no follower of intellectual fashion or abuser of cliches. He could see right through you. He often saw right through me. I didn’t realize I was mouthing bullshit until Jerry called me on it, and forced me to go deeper in my thinking..

We were fine on our own for those lunches, but now and then we’d ask someone else along. He did not stand in front of a classroom but he was more of a teacher than most of my colleagues on the faculty. The students adored him and often wanted to join us.

Of course we’d eat, but the point of the meal was to share time, that most precious of commodities.

When I think of childhood dinnertimes, I don’t think of the food — though both of my parents took great pleasure in cooking. I think of the time spent.

At the time, lunch with Jerry was lunch with Jerry. Only later, decades later, did I realize what Lunch With Jerry had meant.

He always busted my chops. He’d see my empty plate and do a double take worthy of Curly in a Three Stooges two reeler.

“McKeen, you don’t fuckin’ eat — you inhale.”

What I wouldn’t give to have him good-naturedly berating me right now. He always used the expression “stacking shit.” So he would want me to say what I miss is him stacking shit on me.

Yeah, that’s more Jerry-worthy.

What I want to say: Eating is more than nourishing our bodies. We show our humanity across the table, and over food. We break bread. We dine with friends. We talk. We show our love.

I find myself thinking of the song “Bob Dylan’s Dream”:

How many a year has passed and gone?

Many a gamble has been lost and won

And many a road taken by many a first friend

And each one I’ve never seen again

I wish, I wish, I wish in vain

That we could sit simply in that room again

Ten thousand dollars at the drop of a hat

I’d give it all gladly if our lives could be like that

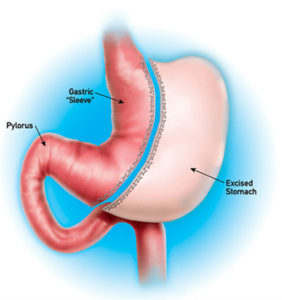

Jerry has been gone for years now. I’m here in the kitchen. The boys are with their mother tonight and this large house is too quiet. It’s raining outside and I stand over the sink in the pathetic dance that we single men do — eating, standing up, trying not to make a mess, trying not to dirty a dish. Now, with my innards rearranged, I no longer have the capacity for a meal. I eat only to stay alive.

The gastric surgery has changed my life, and quickly. Eating too fast or too much means pain. My new body can’t do the job my old body used to do. I must retrain this carcass yet again.

I’ll figure it out, but these first weeks are hard, especially as I stand there at the window, doing the single-man dinner dance I thought I’d left behind.

I think about the great meals of my life — at an open-air bar in the Florida Keys, a table in the courtyard of Joe Garcia’s in Fort Worth, the upstairs at Commander’s Palace, or a long-gone burger joint in Norman, Oklahoma — and think about those moments and those friends and think those are the moments that will unspool (assuming I get the chance for that final midnight showing) on my deathbed.

I wish, I wish, I wish in vain that we could sit simply in that room again

Yet here I am — standing over the kitchen sink, alone.

What I want to say:

Eating is more than nourishing our bodies. We show our humanity across the table and over food.

We break bread. We dine with friends. We talk.

We show our love.

hour before I woke up in the emergency room.

hour before I woke up in the emergency room. I’d had an ambivalent relationship with religion, which was a human construct. Though I grew up in a home with reverence, and been baptised a Methodist, we’d never gone to church and in adulthood I drifted toward Catholicism, mostly because I kept dating Catholic women. I converted at age 34, and for a period I was even a lector at our church back in Florida.

I’d had an ambivalent relationship with religion, which was a human construct. Though I grew up in a home with reverence, and been baptised a Methodist, we’d never gone to church and in adulthood I drifted toward Catholicism, mostly because I kept dating Catholic women. I converted at age 34, and for a period I was even a lector at our church back in Florida.

I rarely used that other F-word, the one about weight. I felt that I was self-aware of my body and its myriad faults.

I rarely used that other F-word, the one about weight. I felt that I was self-aware of my body and its myriad faults.

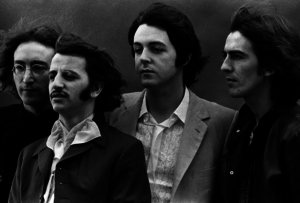

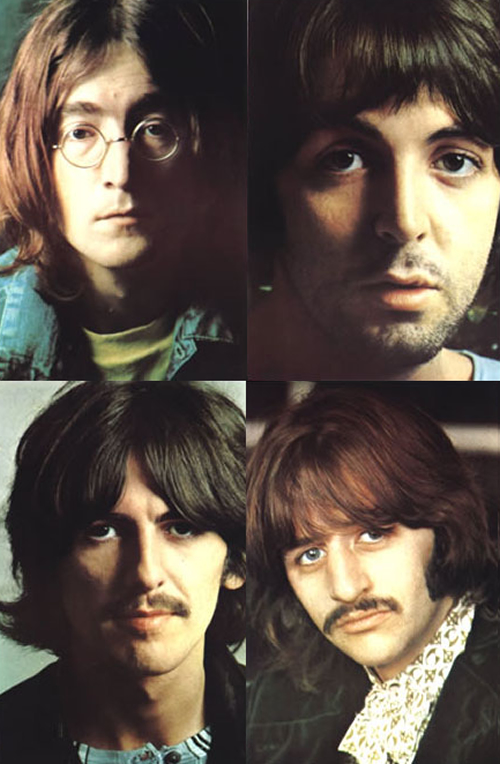

Things had changed by 1968 and I was ready when the White Album hit. Back then, young sprogs, our parents didn’t just buy us stuff and we didn’t get handed an allowance. The folks expected us to work for money. And since the White Album was a double-album, I’d need to work extra hard.

Things had changed by 1968 and I was ready when the White Album hit. Back then, young sprogs, our parents didn’t just buy us stuff and we didn’t get handed an allowance. The folks expected us to work for money. And since the White Album was a double-album, I’d need to work extra hard. Without help, I spent a day working in the back yard. When I called my father outside at dusk, he marveled at my work, then handed me a $10 bill. I rode my bike to the Woolworth’s — luckily, owing to the early sunset of November — only a half mile away. The album was mine.

Without help, I spent a day working in the back yard. When I called my father outside at dusk, he marveled at my work, then handed me a $10 bill. I rode my bike to the Woolworth’s — luckily, owing to the early sunset of November — only a half mile away. The album was mine.

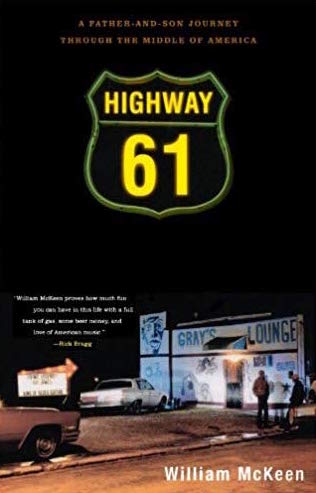

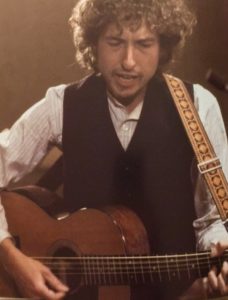

Dylan had second thoughts. He played the acetate of the album for his brother while visiting Minnesota in December. David Zimmerman told big brother he could do better. Or something. But he hired a studio, found some local musicians, and got Big Brother Bob to re-record half of the album.

Dylan had second thoughts. He played the acetate of the album for his brother while visiting Minnesota in December. David Zimmerman told big brother he could do better. Or something. But he hired a studio, found some local musicians, and got Big Brother Bob to re-record half of the album.

There are a few neighbors with whom I converse, but mostly I have smile-and-nod relationships with the people in the houses around me.

There are a few neighbors with whom I converse, but mostly I have smile-and-nod relationships with the people in the houses around me. This girl is in second or third grade, I would estimate, and her younger sister I would guess is in kindergarten. Their parents are nice in a nod-and-smile way, and her father is the only person in the neighborhood, other than me, to do yard work. I am his Brother of the Bramble. Everyone else hires landscape companies.

This girl is in second or third grade, I would estimate, and her younger sister I would guess is in kindergarten. Their parents are nice in a nod-and-smile way, and her father is the only person in the neighborhood, other than me, to do yard work. I am his Brother of the Bramble. Everyone else hires landscape companies.

Beef and Liam interviewed Robbins for the final piece in the book and it contains this wonderful passage:

Beef and Liam interviewed Robbins for the final piece in the book and it contains this wonderful passage: I sent these sets to my mother, brother and sister with instructions that they not be opened until June 14, dad’s birthday.

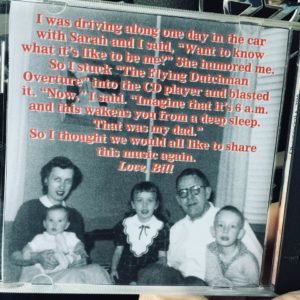

I sent these sets to my mother, brother and sister with instructions that they not be opened until June 14, dad’s birthday. Think of how much of your life is defined and preserved in musical memory. I was driving to the ferry terminal this morning, serenading — at top volume — the sleeping denizens of Nantasket Avenue with Wagner’s ‘Death of Siegfried.’

Think of how much of your life is defined and preserved in musical memory. I was driving to the ferry terminal this morning, serenading — at top volume — the sleeping denizens of Nantasket Avenue with Wagner’s ‘Death of Siegfried.’