Will you look at this beautiful thing?

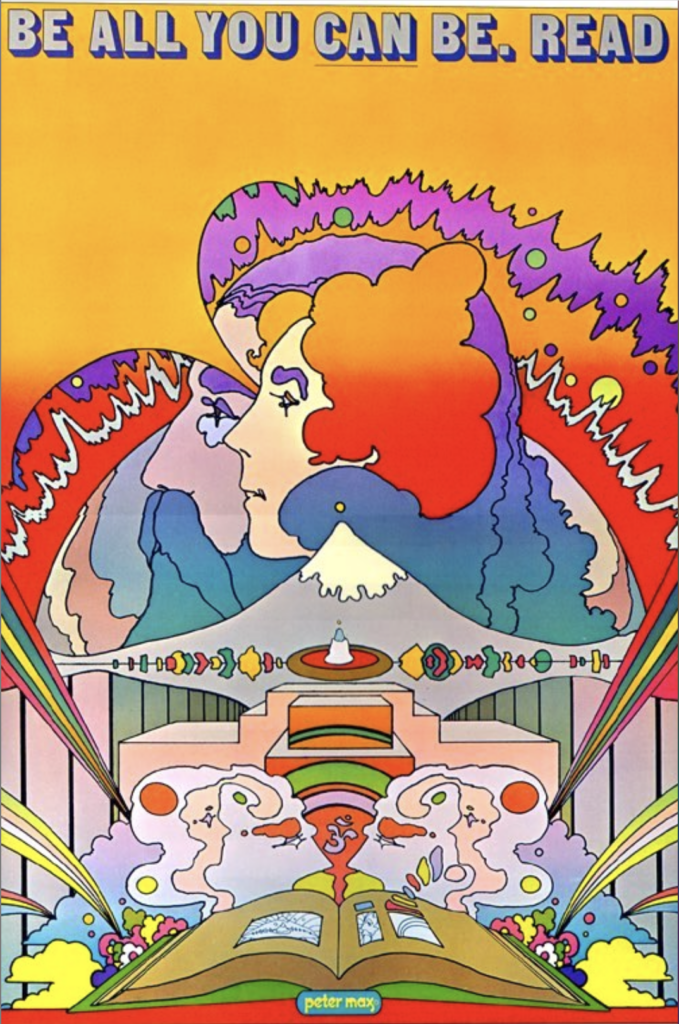

I’ve had this poster, framed, in my house for more than a half century. Before the United States Army co-opted the slogan “Be All You Can Be” for its recruiting efforts, that was the slogan of National Library Week, with that one crucial addition — “Be All You Can Be: Read.”

I’ve always taken that saying to heart. When I think of my father, who died when I was 20, I think of him with a book in his hand. He was never without. There was a book on the arm of his chair and one at the breakfast table and one in the formal living room. He always had one on the front seat in case he got stuck waiting in a parking lot or at a long stoplight.

And now: I have become him.

As the saying goes, “Children learn what they live.” I’m rarely without a book. I start my day with coffee, newspapers (one on paper, two digital), then push back in my tattered leather chair for an hour of quiet, alone and lost inside a book.

This poster by Peter Max was published to celebrate library week in 1969. Max’s work was ubiquitous then. Collectors were paying enormous amounts for his work, but I’m proud to report that I got this beautiful thing for free.

I was a mid-teen that year, transitioning to high school, though it was on familiar turf. I was a student at Indiana University High School in Bloomington, part of a kindergarten- through-Grade- 12 school that had been an experiment managed by the university’s School of Education. Super-secret and newfangled teaching techniques were loosed upon students at the school. In fact, the original team name of the school’s mascot was the Guinea Pigs.

But then, in the early 1960s, the school moved from the heart of the university campus to the fringe. The new school was built with shiny metal roofs and was split into a series of buildings. It always made me think of what a small liberal arts college on Mars would look like.

We also became the Univees. I have no idea what a Univee is,

Soon, we were no longer so experimental and the university passed us off to the local school system and what we called U-School was phased out.

I was in the last class to graduate, the class of 1972.

The building in the heart of our Martian campus was the library.

Let us now praise wonderful librarians. I can’t tell you how much I’ve learned from archivists and librarians over the course of this life. Because of my work, I’m often in the lovely hives of a library.

Whether it’s a towering university library (Indiana boasted for a time of the largest university library west of the Hudson) or a cozy small-town ediface (I thanked the staff of the Cohasset library in Massachusetts in my book Everybody Had an Ocean), I find some of the finest people I’ve known behind the desk, ready to help.

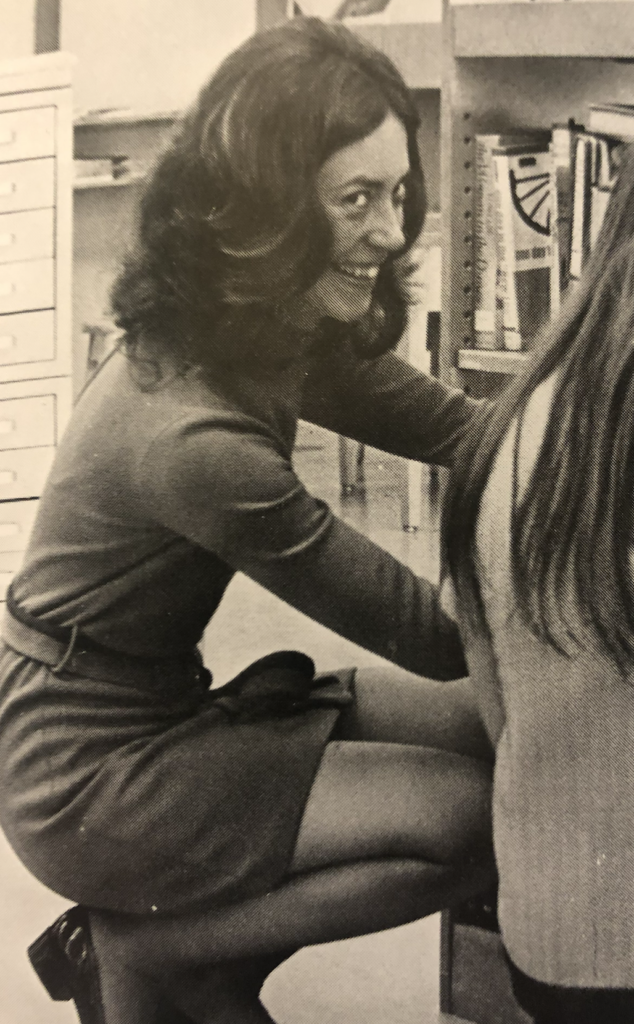

At University High School, we were blessed with two great librarians: Norma Miller was in charge and was assisted by Pamela Brown.

Keep in mind. I was a kid with my hormones on a full, rolling boil. There was a reason I rarely ate in the Commons, but instead spent lunch hour in the library.

I was in love. I ached to be older, to be someone with whom Pamela Brown wanted to spend time, perhaps over a cup of coffee, discussing great literature. Too bad I had not yet learned to tolerate coffee. Too bad — as her courtesy title made clear — that she was already married.

There was a reason all of the boys in my class enjoyed trips to the library.

Mrs Brown was beautiful but also kind and encouraging. (Can’t seem to refer to her coldly as Brown or Pamela Brown. She was Mrs Brown then and always will be.)

One day, not long after the spring semester resumed, I came into the library and she was standing behind the counter, and for once something other than Mrs Brown drew my attention.

“That just came in this morning,” she said, nodding at the poster. “Beautiful, isn’t it?”

I was speechless, a rare thing for me. We both silently beheld the poster for a while, loving the psychedelic artwork, the image of the Youth following a path set by the Seer.

And that slogan. It expressed to me the beauty and splendor of reading, of passing on our legends and tales and knowledge, of learning what it was like to be another.

Not that I was much of a reader then. I’d read a few serious books — let’s say “grown-up books,” since “adult books” has a different meaning —and was pleased with myself for moving past my Hardy Boys obsession from a few years earlier.

Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter had affected me deeply, as did A Separate Peace by John Knowles. I read A Shropshire Lad by A.E. Housman and Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology. Those works of poetry have always stayed with me.

Mrs Brown encouraged me to read Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut. “He’s from Indiana,” she told me, as a special inducement. I was always on the lookout for great Hoosiers. (I later learned that my great Aunt Inez had known Vonnegut since he was a little boy.)

Slaughterhouse-Five was followed by other suggestions. Somehow Mrs Brown sensed, without us really talking much, that I was on my way to being a reader. From that point, I was gone.

(We didn’t talk much because I was pathologically shy. I was often nervous and tongue-tied in her presence. Still, she spoke to me a lot. Her eyes told me she was aware of my infatuation.)

What was important: Mrs Brown recognized the reader gene in me and made sure it was watered and manured to maturity.

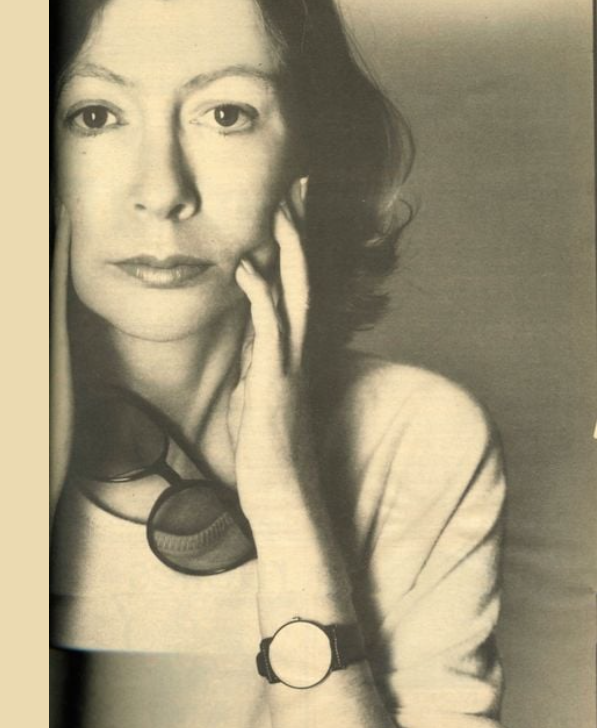

I spent most lunches in the library, usually plopping down in an easy chair to read magazines. ’Twas there, in that library, when I read Joan Didion for the first time.

Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, shared a biweekly column called “Points West” in the Saturday Evening Post.

This particular Didion column was about a young woman so desperate to be a movie star that she used her savings to buy a full-page ad in Variety, announcing that she was going to be famous.

Didion drove to the young woman’s house and took her for a ride, then recounted their conversation in her column.

I saw this as a tragedy in the making and a couple years ago, curious about what happened after Didion’s article, looked up the young woman’s screen credits. She had two: Shattered if Your Kid’s on Drugs and Blood Orgy of the She Devils. No idea what happened to her after that.

For once, I turned the tables on Mrs Brown. At the end of lunch hour that day, I took her the copy of the Post with Didion’s article on the wannabe movie star. “You should read this,” I said. “It’s good.”

When I came in the next day, she said, “You were right. That was a great piece.”

A few years later, I worked at the Saturday Evening Post and loved to steal afternoons in the archive, reading every column (I’m pretty sure) that Didion wrote for the magazine.

I owe so much to that library — to Mrs Miller and Mrs Brown. A word of encouragement and a simple act of kindness can mean so much to a kid that age. As a teacher, I always wanted to be like Mrs Brown. She set the bar high.

I was one of the last days of the school year and everyone was getting restless to get the crank rolling for summer.

I came into the library and before I was much inside the door, Mrs Brown was standing in front of me.

“We’re getting ready to close up for the summer,” she said. “I thought you’d want to have this.”

What she handed me was folded into a neat rectangle. I didn’t need to open it to know what it was.

My face must’ve flushed. She smiled indulgently.

She’s probably in her eighties now. I hope she’s still with us — that she’s out there somewhere, still having a good life. I hope she’s still reading, still helping people.

I want her to know that her gift has been hanging on the walls of every one of my homes over the last half century, and that every time I look at it, I’m reminded of her kindness and encouragement.

Thank you, Mrs Brown. You made such a difference in my life.