I miss writing book reviews.

In the 1980s, I became a prolific book critic for the Orlando Sentinel. Around 2000 or so, I began writing for the St. Petersburg Times (now the Tampa Bay Times) and then added Creative Loafing to the list by the mid-2000s. They even designated me book editor for a while. Since moving to Massachusetts, I continued with Creative Loafing for a few years and wrote a dozen or so reviews for the Boston Globe.

Alas, the Sentinel, the Times and the Globe have cut back much of the space that used to go to books.

I miss the reviewing and I miss working with book editors, especially the late Nancy Pate (Sentinel) and Colette Bancroft (Times).

I also miss being able to tell people about good books to read.

So, if you have interest, I’ll give you one-or-two sentence reviews of the stuff I’ve read so far this summer. (And it’s been a good summer — Michael Connelly, Carl Hiaasen and Stephen King all released new novels in May.)

. . . . . . . .

Mark Twain by Ron Chernow (Penguin, $45)

This book is huge (1,174 pages) and it sometimes difficult to read because of its size. We need to have a lecturn and a page turner to read this.

But the content? Can’t remember if I’ve read any biographies of Mark Twain, though I did read the first part of his autobiography, about his early days in journalism.

I can’t imagine any biography topping this one. Ron Chernow has amassed an enormous amount of information and woven it into a rich, lively narrative.

He’s also assessed Twain — Sam Clemens, of course — by today’s standards, discussing the question of his racial attitudes and his banning by school boards.

This is a tremendous book and will be the fastest 1,174 pages you’ve ever read.

. . . . . . . .

What Kind of Paradise by Janelle Brown (Random House $30)

This is a wonderful novel.

Imagine: the Unabomber took his 4-year-old daughter to the cabin when he went off the grid. Fourteen years later, she leaves behind the only life she’s known in order to discover the free world.

That’s essentially the plot of What Kind of Paradise by Janelle Brown.

There are few novels where I feel I am absolutely inside the head of another human being. I recall Sam, the adolescent girl in the middle of Bobbie Ann Mason‘s brilliant novel, In Country. Fatherless, she seeks to learn about the identity of the man who died in Vietnam before she was born.

Yea, me, an old guy … I feel that I am inside a girl’s head at a time of turmoil.

This is why we read — or at least, that’s why I read.

This book so well recalls Mason’s ealier masterpiece, which came out in the mid-1980s.

I thank both authors for taking me into a world so unlike my own.

. . . . . . .

To Anyone Who Ever Asks by Howard Fishman (Dutton, $32)

Speaking of disappearing, this nonfiction book tells the story of a unique and much admired singer-songwriter, ahead of her time, who just … disappears one day, never to be heard from again.

It’s another huge book, so well done that you find yourself ripping through this telling of Conne Converse‘s life.

It makes us thirst to hear her music, much of which is difficult to find. This calls for a significant eBay seaarch.

Howard Fishman tells her story with grace and does not waste a word. It’s another huge book so well done you are propelled through the narrative.

This book came out a couple of years ago. You’ll probably have to order it from your friendly neighborhood bookseller.

. . . . . .

Fleishman is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner (Random House, $27)

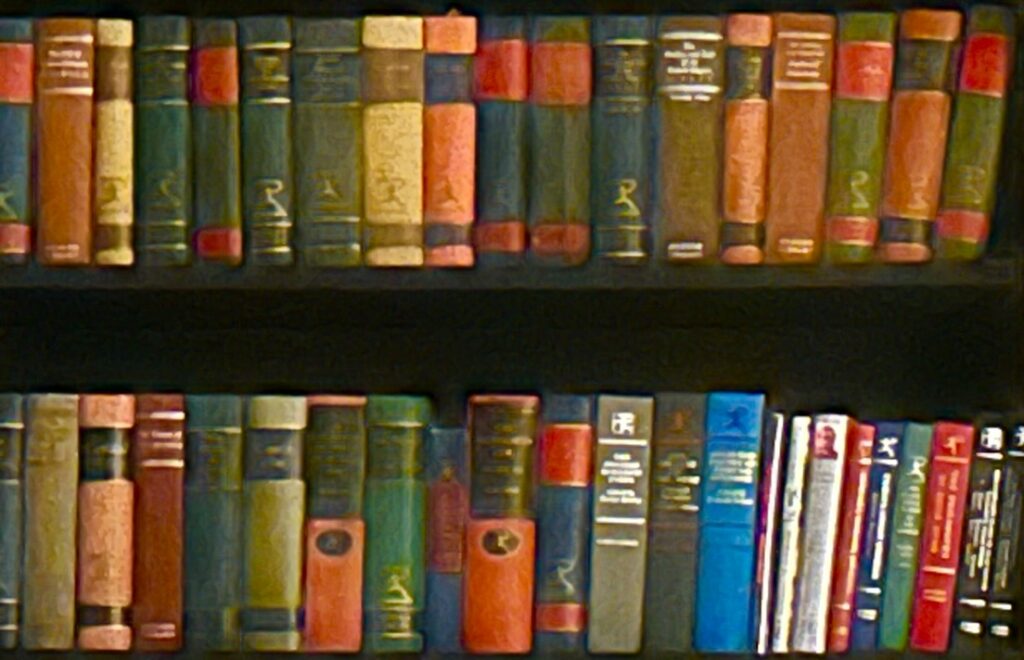

I’ve read both of Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s novels this summer. (You can see Long Island Compromise at the right in the picture.) Fleishman is her first novel, and it came out in 2019. It’s the story of a marriage falling apart and a spouse who disappears.

This book was utterly absorbing. I carried it with me wherever I weant and would steal moments at long stoplights to jump back into the story.

By the way, it was adapted by its author, whose unwieldy name invites typographical errors. The television adaptation (which starred an excellent Jesse Eisenberg) is on Hulu, if memory serves.

If you’re not married, this book will make you sink to your knees and thank a higher power that you are single.

. . . . . . .

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler (Knopf, $27)

I’m an Anne Tyler junkie and have read all of her novels. Those books are like three-course meals as she explores the minds of characters caught between the familes into which they were born and the families they choose.

This novel is short, yet full of the characteristic Tyler insights and observations. It’s not that huge meal, but more like sampling a few appetizers. Tapas! Short enough to read in an afternoon.

Her writing is perfect. I urge you to read all of her work. Start with Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant or Saint Maybe.

I’m so glad I had a friend who turned me onto Tyler because she said I reminded her of the protagonist in Saint Maybe. I had to read that book to see if I too saw the resemblance. I did (it as a compliment) and I was hooked by Anne Tyler.

. . . . . . .

Nightshade by Michael Connelly (Little, Brown, $30)

Michael Connelly is my crack. I confess my addiction up front.

I’ve never met a Connelly novel that I did not immediately devour.

Connellly has so many great characters — Harry Bosch, Renee Ballard, Mickey Haller, Terry McCaleb, Jack McEvoy and others. This book introduces a new character — Stillwell, a detective who’s been exiled from downtown LA to Catalina Island.

I’ve never been to Catalina, but after Conelly’s evocative writing, I feel like a local.

Seriously: this guy’s writing is intoxicasting as a drug.

Light up! Enjoy, before his novels are designated controlled substances by the DEA.

. . . . . . .

Fever Beach by Carl Hiaasen (Knopf, $30)

Carl Hiaasen‘s books are propelled by rage humor. He’s so angry at injustice that he can only channel his operatic temper through vicious comedy.

How many authors — after 30 years of writing novels — are still peaking? Hiaasen’s last novel, Squeeze Me, was his masterpiece. Fever Beach is a suitable follow up.

The world sucks and it’s being run by assholes. You will enjoy his rage against the machine.

And by the way, you will not find a word out of place. This man is an immaculate storyteller.

. . . . . . .

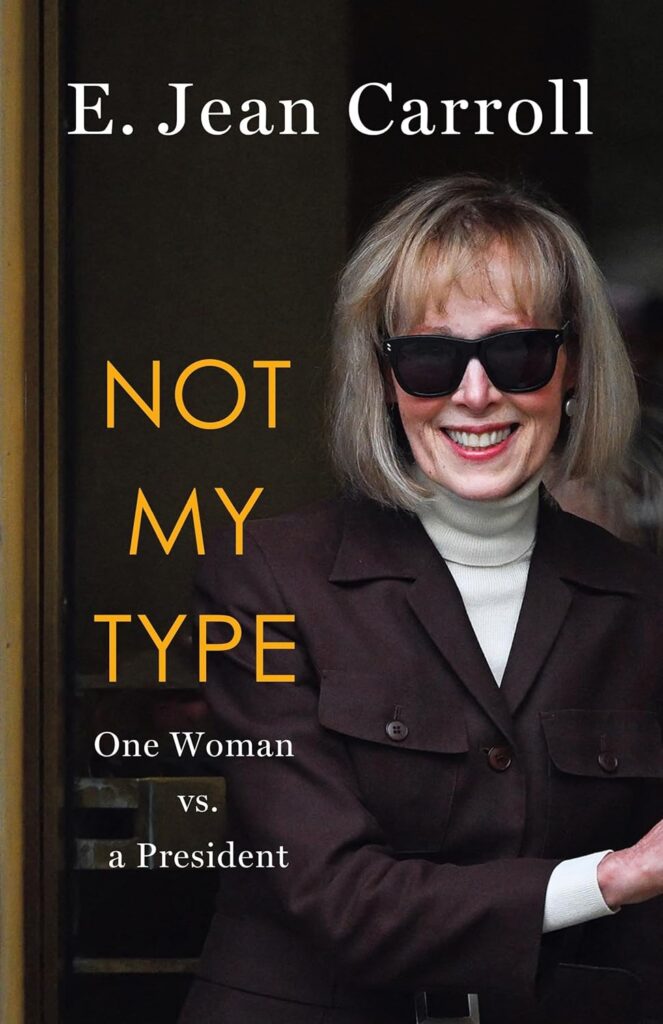

Not by Type by E Jean Carroll (St. Martin’s, $30)

E Jean Carroll reached out to me in the early 1990s after I’d published my first book on Hunter S. Thompson and she was working on hers.

We crossed paths online again years later when my BU administrator turned out to be E Jean’s former PA. Plus, E Jean is an Indiana University graduate. And … a cheerleader! There’s a good chance I lusted after her when I as a high school kid in the stands and she was jumping like popcorn on the sidelines.

Not My Type is Carroll’s account of her Trump trials. It’s unsparing, brutal and quite funny at times.

And I have always liked E Jean’s humor. I now also admire her resiliance and restraint.

I’ve read a lot of Trump Porn, including excellent books by Bob Woodward and Maggie Haberman. This book is a must-read for all of you out there preparing articles of impeachment.

. . . . . . .

A Few Words in Defense of Our Country by Robert Hilburn (DaCapo Press, $34)

It’s been a Randy Newman summer here at the ol’ homestead.

What a great artist! Has there ever been a more vicious song than “Sail Away”? His songs should be used to teach American history.

Robert Hilburn gives us the blow-by-blow of Newman’s life and gives us a new appreciation of this American treasure.

Hilburn’s writing is exceptional.

Alas, I wish the publisher had a better copy editor. I was shocked by not only the copy editing but the presece of a few minor errors of fact. Minor they may be but if newspaper and book publishers paid and respected excellent copy editors, it would be an even-more-groovy world.

. . . . . .

Hold the Line by Michael Fanone (Atria Books, $28)

I’ve been interested in this guy ever since he came into mass consciousness after the January 6 attack on the nation’s capitol.

Michael Fanone has written a powerful memoir. He was defending the Capitol on January 6 and was tasered by the rioters. He suffered a heart attack and a brain injury.

The first part of the book deals with his earlier career as an undercover cop. It’s nice to see the lid lifted on policing and Fanone does not shrink from telling the bad along with the good. This part reminded me of Serpico by Peter Maas.

Fanone holds back nothing. He drops a lot of fucks and motherfuckers here and there, and does so deftly.

Some of these words are used to describe such weasels as Jim Jordan of Ohio and Lindsay Graham of the great state of South Carolina. Those guys are botches of humanity. Same goes for Kevin McCarthy.

When you finish this book, you will want to call Fanone and ask him to run for congress.

He holds nothing back. He is a great American.

. . . . .

Never Flinch by Stephen King (Scribner, $32)

Steve, Old Boy, I enjoy your work but can you cut back on the appositives and all the off-on–tangent parenthetical stuff?

Minor bitches, these.

Stephen King once again gives us his wonderful protagonist, Holly Gibney, who first showed up in Mr Mercedes.

King said she was planned as a minor character who soon grasped his heart. he has confessed that he fell in love with her.

That’s understandale.

King just keeps getting better and better.

These Gibney novels are catnip. Read them in whatever order you want. The Mr Mercedes trilogy is a good place to start. Or you can start with The Outsider.

Get off your ass and read one of these books!

. . . . .

I’ve also been reading a lot of older stuff this summer.

I’ve been on a hard-boiled crime-fiction binge, reading James M. Cain, Jim Thompson and Raymond Chandler. I love the way those dudes write. I believe they can clear out all the useless stuff in our brains. Reading their books is like using a mental supposiitory.

I also read the only major work of Flannery O’Connor‘s that I’d never read — The Violent Bear it Away. I’d read her stories, her only other novel (Wise Blood) and even her prayer journal. I was surprised by the fluid nature of this narrative. It was one of those novels you inhale.

If you’ve never read any of her work, I urge you to read Flannery O’Connor. She is life-changing.