Daughter Sarah called the ambulance over my objections, but what else could she do when I had so obviously lost control? I was suffering a cognitive malfunction (I suppose that’s a polite, clinical term for saying I was fucked up) and desperately needed help.

I barely remember the ride to the hospital, too preoccupied by what had just happened.

I was thinking I was all right, but as I sprawled on my couch with Sarah and the two emergency medical technicians and was unable to come up with the names of everyday items — keys, coffee cups, shoes — that they held up before me.

I was in serious trouble..

I’ve always been the kind of guy who doesn’t want to make a fuss and who is embarrassed by attention. I didn’t quite feel myself stepping backward into the fog (as I had when I first died years before, in New Mexico) but the inability to talk or to approach anything with reason, was scary.

At the hospital, I hoped to find out what was wrong — but also was afraid of what I’d learn.

The ambulance arrived at the hospital’s emergency bay amid lots of shouting and scrambling around by all of the nurses and EMTs. As someone who often wilts from attention — everywhere outside the classroom, where I hope for attention — I was on the verge of humiliation. There I was, inert on a stretcher, with a variety of anxious faces looking down at me, asking questions.

With my cognition so impaired — that was the scariest thing about all of this — it was Sarah who answered all of the urgent questions with an efficiency and urgency. The medical staff found her helpful in the extreme.

I was moved to a three-walled room in the emergency suite, shut off from everyone else by a curtain. They allowed Sarah in with me, and she was repeating everything she had told the EMT’s and the first-line-of-defense people at the ER. Now she was talking to the nurse who would actually be overseeing me.

I was oblivious. My head is usually a gumbo of the long-lost jetsam taken residence in my skull. At any time, I have a bubble of remembered literature floating into some long-forgotten song, as well as the images of family and the pieces of time I store, those moments that for good or ill I’ve replayed in my cranial cinema for all of my life.

But all of that was gone. My brain was empty as a white-on-white room. All things were muted. I was in the hospital bed, but when Sarah and the nurse spoke, it was if I was buried under a Kilimanjaro of pillows. The voices came from far away, traveling slowly. Seemed that a question was followed by a full minute of silence before the answer. I’d stepped inside of time and pushed at the walls, like a low-rent Steve Reeves in Hercules Unchained.

Inside this expanding time, I had trouble following the conversation until the word surgery dropped like a ripple in a pond.

Until the coming of this routine (sorry, Dad) knee surgery, I’d never feared going under the knife. I would add up the number of surgeries I’d had in my life, but I can’t count that high.

In a strange way, my previous surgeries had not only worked, but somehow provided an odd kind of comfort. It was always good to know that I would continue to function, that these trained people had opened me up, goofed around with my organs, and that I’d survived and would, no doubt, continue to live.

When the nurse left to go get some paperwork for Sarah, I turned to my eldest (and trustworthy) child, now a woman in her late 30s, and offered my contribution to the emergency-room discourse.

“Please,” I whispered. “No spinal.”

“I’ll tell them,” she said.

“That’s how this all started.”

My father was a good man and would never want to embarrass anyone, especially his youngest son. He’d never say I told you so, but I felt it. It had not been my choice to go through the knee surgery under a spinal block, but I knew I’d never do it again.

I had the usual meds, the ones that make patients relaxed and silly, and then they came to take me away to surgery.

“Who’s the doctor?” I asked. I wonder if they’d called in Clifford Gluck. He was the urologist I’d first seen a couple of years before, when this whole health walkabout began. I visited him to see how it would go if my vasectomy was reversed and I would procreate again.

And then everything happened — cancer and all of the stuff that followed.

“It’s Dr. Tracy,” the nurse said. He’s the urologist on call.

“My urologist is Clifford Gluck,” I said. “Shouldn’t we call him?”

(I’d never felt so old as I did at that moment when I said my urologist.)

“We don’t have time,” the nurse said. “Dr. Tracy is on duty.”

I did not meet Keith Tracy, my new urologist, until after the surgery. He was a busy guy that day.

I’m not sure about what they did during that surgery, but I came to afterward, back in the same room. Before I opened my eyes, I heard the soft sounds of fingers on keyboard.

Was I writing in my sleep?

When my eyess opened enough to focus, I saw Sarah sitting next to the bed, working on her laptop. She is an artist of multi-tasking.

She has a demanding and rewarding job in New York, yet kept up with her work while managing our part of the surgery. She hadn’t even had to take a day off. That’s the McKeen work ethic in practice.

I’d have to spend the night in the hospital, but I felt I was recovering well enough for Sarah to leave. I insisted. I felt like I’d disrupted her life enough. Besides, Nicole had volunteered to help if I needed anything.

My room was comfortable, like all of the accommodations at South Shore Hospital. Too bad hospitals don’t give points for each stay. I would have earned a few medical vacations.

If my brain hadn’t been so exhausted, I’d try to recall all the nights I’d spent at South Shore. But I was too tired.

I settled down into the hospital routine. You actually don’t get a lot of rest in the hospital, since you are awakened every couple of hours for them to test vital signs. Plus, I was catheterized, so the nurses also had to keep track of my urine bag.

The day after the surgery, I met my new urologist, Keith Tracy. He was an affable guy, probably about half my age.

He talked a little bit about the procedure, but he buried the lead, as we say in journalism.

“We came close,” he said. “You were about 20 minutes away from being dead.”

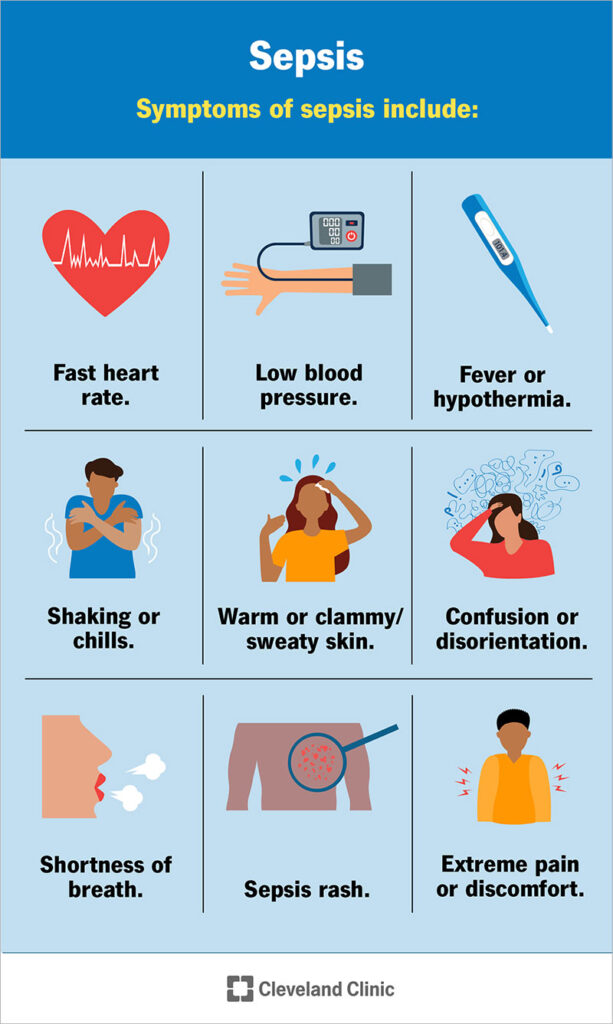

I had sepsis. I knew little about it, but I knew it was serious shit. Thank God for my iPhone. The often moody Siri overcame her grudge against me and offered this definition:

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition that occurs when the body’s immune system overreacts to an infection. This overreaction can lead to widespread inflammation and organ damage. It is a systemic infection with life-threatening organ dysfunction .

So after a few days in the hospital, I was sent home. There was a catheter with a tube down my leg that led to a bag that I had to change now and then.

I could never tell when I was urinating. It was like a tap, turned on all of the time.

I thought, I could live with this. But I knew things were more complicated than that. Of course.

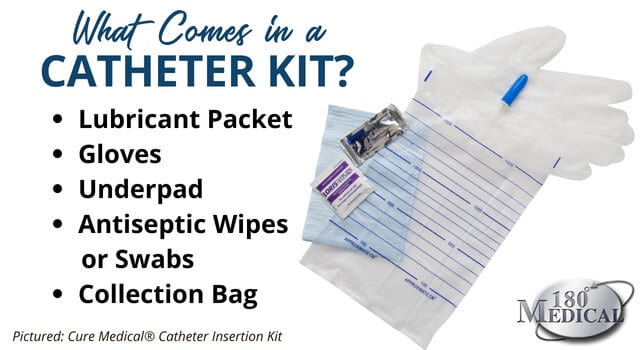

In my follow-up visit at Dr. Tracy’s office, he had one of his nurses show me how to self-catheterize. (Self-cathing as we say in the trade.)

This was tough. First, I had to wash my hands, then put on rubber gloves. Then I had to clean Mr. Happy with an alcohol wipe. Once that was done, I had to face the catheter. It was a plastic tube, about a yard long.

That’s right — a yard. Thirty-six inches of plastic tubing.

Imagine: you insert that thing up the Ol’ Mississippi and it pulls all that pee from your bladder that doesn’t come out the usual way.

You use a lubricant, like KY Jelly, to limber up the catheter, and you add a little bit to the crown of Mr. Happy’s head, to make for smooth sailing as the tube is inserted.

There are many adventures on the journey. At a certain point, the tube has to negotiate its way past the prostate gland. This requires an intake of breath and holding of same. It’s kind of like the Jungle Cruise at Disney World. Once we are safely past the rapids (prostate), we wait for the tube to drop into the pool of urine.

Stop immediately when the flow begins. Push too far and you piss blood. (That happened on several occasions.)

I’d always hated catheterization. I remember my first surgery, a hernia operation when I was 20. The nurse (a male, but insensitive to this procedure) seemed delighted to shove what I was sure was a garden hose up my willy.

That was miserable and peeing was painful for days afterward. From that point on, I asked nurses to delay the cathing until I was under anesthetic. I feared cathing more than any surgery.

All of this happened as the school year was beginning. My administrator and good friend, Sarah Kess, had been managing the office in my absence. There was some concern in the college administration about whether I could return or whether I’d need another medical leave.

I was determined to get back in the classroom.

I was not ready to return immediately, so Sarah K (the K is my Kafkaesque way of keeping her straight from my daughter, Sarah M) covered my classes the first week. She mostly told the students I had had a medical emergency but that I would be back next week.

I wondered if maybe I did need a medical leave. When I looked in the bedroom mirror I didn’t recognize me. There was a haggard, elderly man in my room. Who is that dude and how did he get in here?

But let’s go back a bit, back to when I was still wearing the nurse-installed catheter with the tube down my leg into the bag of whole goodness attached to my ankle.

Dr. Tracy’s nurse had not yet taught me to self-cath when I made it back to the university. I still had the bag at my ankle, still had to visit my urologist’s office to get the catheter replaced every other day.

I was moving slowly. As often happens after surgery, the primary feeling is of fragility, not pain. And that’s what I felt. I used my cane and treaded deliberately.

Thank God for public transportation, which saved me hundreds of steps. I took the ferry from the next town over, Hingham. It was a quiet, often beautiful ride and afforded time and atmosphere for cat napping.

When we arrived at the dock, there was a short walk to the subway. There was one transfer and then the subway came above ground and conveniently stopped in front of my building. A wee bit of hobble and I was at my office door.

That would seem to be a full-day’s work, just getting to the office, but my duties were only about to begin.

When Sarah K saw me, I could see myself in her face. She seemed wary and concerned.

“Are you sure you’re ready to come back?”

“I’ve got to do it sometime.”

I sank into the chair across from her desk, where we habitually indulged in our morning debriefing sessions. Those were often the highlights of my day. I know few people with such a terrific sense of humor.

“You look gaunt,” she said. That was my rare moment of joy in those days. Overweight most of my life, I’d longed to be gaunt. Later, Sarah said it would have been more accurate to tell me that I looked near death. Because I was — or recently had been.

My first class was upstairs — and in the same building. I scored on that one, meaning I wouldn’t have to drag my sepsis ass down Commonwealth Avenue to some basement room without windows.

Just one floor up, but I needed to use the elevator.

When I got to class, the students were already there. I made my way to the front of the room.

“I’ve had some health issues lately,” I said. “Would you mind if I sat?”

No one objected, so my carcass collapsed in the chair at the instructor’s desk.

The class was Literary Journalism, something I’ve taught with great joy and relish for decades. I love the subject, so I spent that first day giving the class the lay of the land and getting them stoked — I thought — about journalism that could endure and become art.

I could feel that I was not all there. It’s as if the sepsis had left scar tissue on my brain. I was still not able to retrieve the words I wanted from my skull. But at least I was much improved over my halting, stuttering performance with the EMTs.

Class was a three-hour block, but I asked if we could end early. No one objected.

“Thank you,” I said. “Does anyone have any questions?”

A hand shot up in the second row. “Yeah,” a young woman said. “Are you going to live?”

Good question. I didn’t laugh it off. I told her I’d do my best.

Class over, I moseyed down to my office where I again planted myself in the seat across from Sarah K’s desk.

I told her more catch-up stuff and then ended with what the student had asked in class. I intended that as my closing line of the update, some comic relief.

But Sarah did not find it funny. She urged me to take care of myself.

Then it all hit me: the cancer, all of those medical procedures, my divorce, not seeing the kids daily, my mother’s death. I thought of all of the humiliations I’d had because of my health condition. I’d gotten through it all, but now I had to face this: the self-catherization. This was it. This was the low point of humiliation. I was at the bottom, clawing to get ever deeper.

I had met my limit.

Poor Sarah. She came to work that day to do her job and now there was a blubbering old man in her office.

I was done. This was it. “I can’t take it anymore,” I told her, choking out the words.

And, for one of the rare times in my adult life, I cried.

(And a few of the apparently used the book as a coaster, a practice I find reprehensible.) Still, this book has been read by many hands — hands of people I loved.

(And a few of the apparently used the book as a coaster, a practice I find reprehensible.) Still, this book has been read by many hands — hands of people I loved. But I was into death. From the time I was in single digits, I had a sense of impending death.

But I was into death. From the time I was in single digits, I had a sense of impending death. The astronauts were played by Jack Klugman, Ross Martin and Frederick Beir. As they debated what to do it occurred to me that I was going to die someday.

The astronauts were played by Jack Klugman, Ross Martin and Frederick Beir. As they debated what to do it occurred to me that I was going to die someday.

For someone who drove so much — long, madman drives between Florida and Indiana when I’d steal long weekends to go visit my older kids when they were little — I had a library of death scenarios from the highways. I certainly saw enough accidents and had a lot of close calls. One time, a guy intent on suicide jumped in front of my car but my cat-like reflexes (if you knew me, you’d realize that’s funny) allowed me to swerve at the last minute. There’s a herd of deer in the world that would not exist had I not be able to respond so quickly.

For someone who drove so much — long, madman drives between Florida and Indiana when I’d steal long weekends to go visit my older kids when they were little — I had a library of death scenarios from the highways. I certainly saw enough accidents and had a lot of close calls. One time, a guy intent on suicide jumped in front of my car but my cat-like reflexes (if you knew me, you’d realize that’s funny) allowed me to swerve at the last minute. There’s a herd of deer in the world that would not exist had I not be able to respond so quickly.