Henry David Thoreau was a rank amateur, to hear Christopher Knight tell it.

Sure, Thoreau spent some fine time alone in his cabin by Walden Pond, but he still allowed himself human contact. He’d hit up some friends for dinner now and then. So yeah, in Walden he painted a picture of himself “as solitary as a dervish in the desert” for his two years at the pond.

Hold my beer.

Knight was on total radio silence with humanity for 27 years. Top that, Hank!

Knight was on a drive in central Maine and when his car ran out of gas, he got out and walked into the woods.

Police caught up with him nearly three decades later and in all of that time, Knight told investigators he spoke only one word (“Hi”), when he happened to run into a hiker.

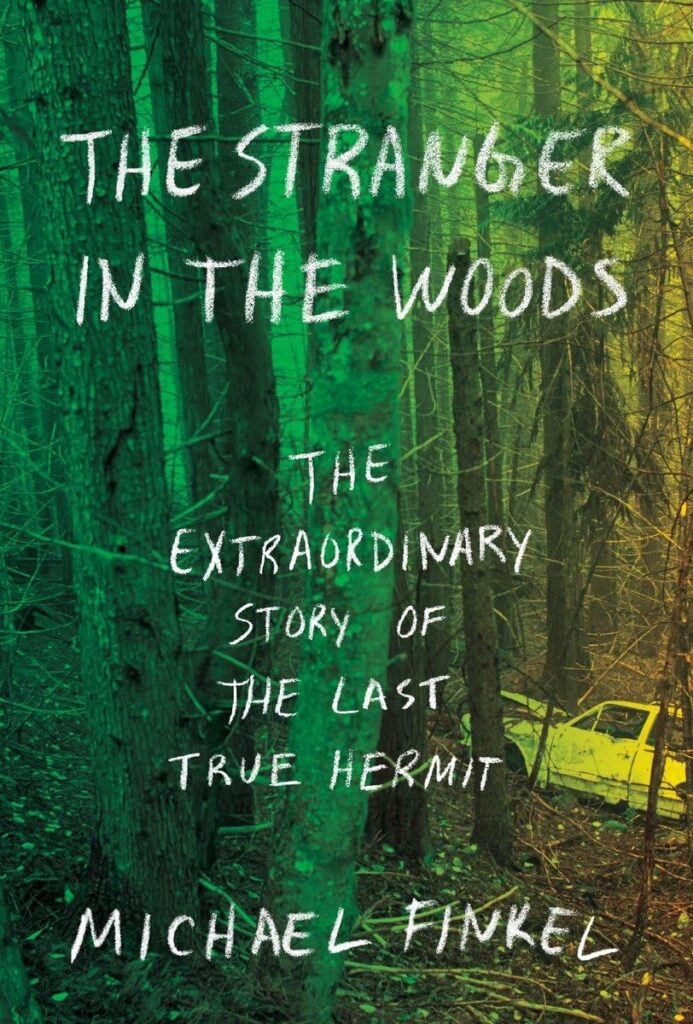

It’s unclear why Knight did all of this. Michael Finkel spends most of his book, The Stranger in the Woods (Knopf, $24.95) trying to get an answer, but the reality is out of his reach, still planted somewhere in Knight’s noggin.

Knight’s family was mildly reclusive, but functional. By all accounts, it was a loving family, just not touch feely, as Knight says. Though all the residents of the area where Knight camped called him “The North Pond Hermit,” Knight disdained that word. He was a stoic, he said, in the classic sense.

I would’ve learned none of this had not Finkel’s book hit me in the nose.

I was reaching for a book off the top shelf in my office and I dislodged The Stranger in the Woods. It caromed off my nose and landed on the floor. I picked it up.

As far as I could recall, I’d never seen this book, had no idea how I got it. But I opened it, read the first sentence, and did not stop until I was finished with the story.

I wonder how the book — published in 2017 — got on my shelf.

I was aware of Finkel. I read his earlier book, True Story, and knew that several years ago he was dismissed from the New York Times for creating a composite character in a story on modern-day slavery in Africa.

When the whistle was blown on that story and the editors sent Finkel packing, he learned that a murderer in Oregon had been operating under the name Michael Finkel. The unraveling of that man’s story was the basis of True Story, later turned into a film with Jonah Hill as Finkel and James Franco as the killer.

I’d liked True Story simply because Finkel was so readable. I often talk about narrative velocity in class and Finkel writes like an X-15.

(I also trusted him. He spent much of True Story apologizing and admitting his shame and remorse. I gave him a chance, and the rest of True Story won me over.)

Knight’s story is still a mystery. Why, at age 20, did he walk into the woods. He hadn’t planned to. He had nothing with him — no clothes, no camping gear. To live, he stole.

He was a polite burglar. He never trashed the homes he entered. He didn’t take the usual valuables — electronics, jewelry, etc. He’d take a can of tuna from a stack of cans in the cupboard. He’d just take one. He might take a tarp out of a shed.

He earned the Hermit nickname early on, and he hated it. He also hated it when people began putting bags of food and supplies on the doorknobs of their cabins. He didn’t want charity.

A lot of those cabins were for weekend or summer use, so they were often empty. Still, Knight never slept in one. He slept outside for 27 years. Did I mentioned that this was in Maine, where they have significant winters.

Yet he never built a campfire in the boulder-shaded home he set up. He stole a propane stove and that was all he had for cooking. He didn’t use it for heat.

When police finally caught up with him — he was spotted on the live feed from a video camera at a camping complex — he asked that his family not be contacted. He had been raised right, he told the cops. He knew that stealing was wrong and he did not want to bring shame to his family.

The story is fascinating. We all make choices. Knight’s was unusual, but you get the sense it was, in some strange way, the right decision for him.