I sing when I’m alone. I have to; no one wants to hear me.

And the song I sing in the shower, or in the kitchen or while mowing the yard — it’s often this one particular song I choose over the others in my cranial repertoire.

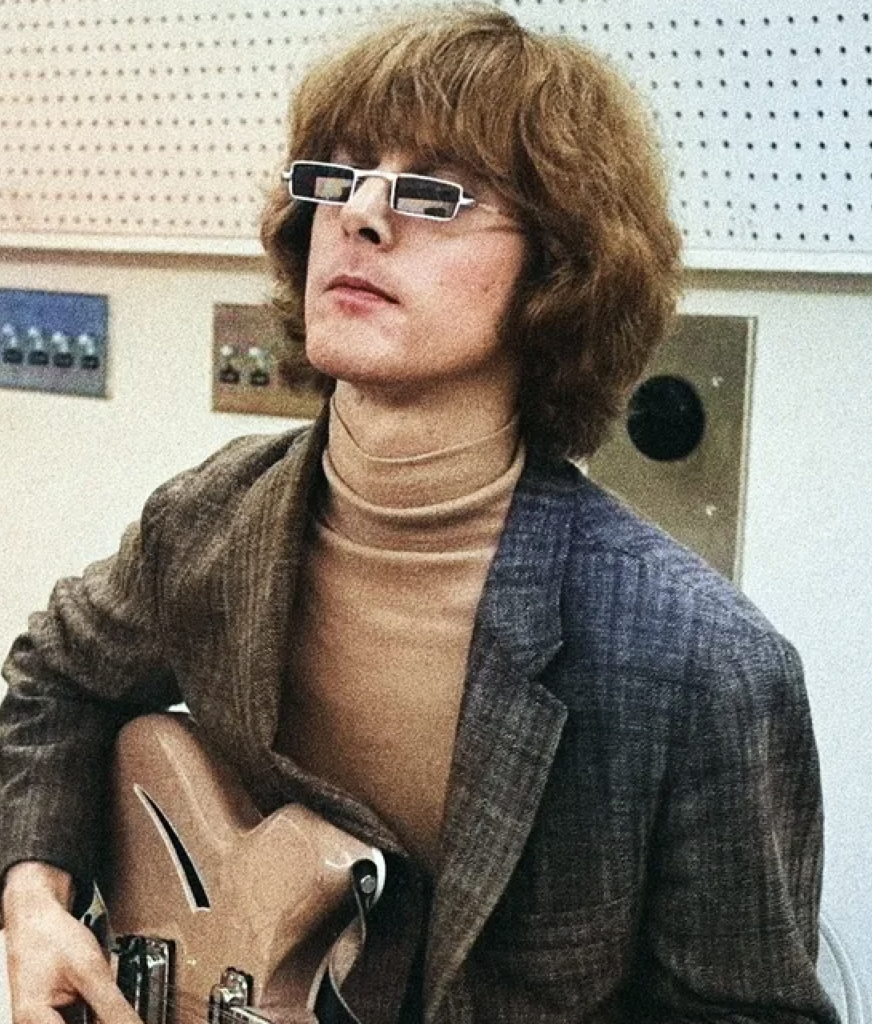

I did not hear the original version first. It came my way thanks to one of my favorite groups, The Byrds.

The Byrds introduced me to lots of things, because the members of the band came from a folk background and weren’t a typical rock’n’roll band.

Thanks to The Byrds, I heard the lovely “John Riley,” a 17th Century English ballad based on The Odyssey.

I first heard the stark and haunting “I Come and Stand at Every Door” on The Byrds album Fifth Dimension. The song was narrated by a child who died in Hiroshima. Now the child appears — “no one hears my silent tread” — to remind us all of the horrors of nuclear war.

It began as a poem by Turkish writer Nazim Hikmet. American writer Jeanette Turner took a translation of the poem to Pete Seeger and urged him to set it to music. With some help, Seeger did so and then The Byrds took the grim message to us kids.

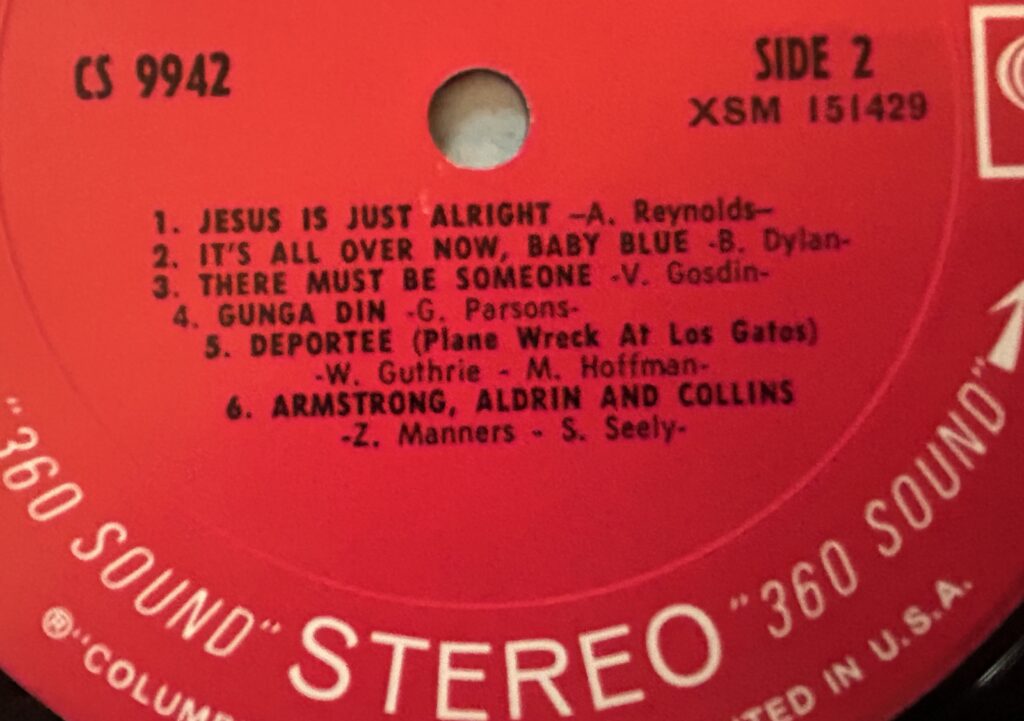

The song I sing when alone was on the 1969 album by The Byrds called Ballad of Easy Rider, where it was titled “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos).”

There have been many variations on the title, and this song also owed its existence in part to Seeger.

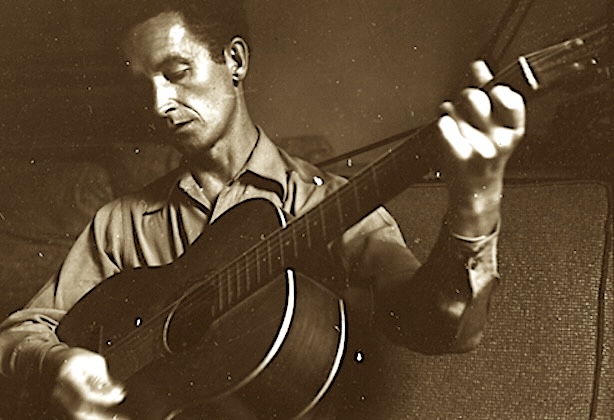

I was a serious student of record labels and I saw the song credited “W. Guthrie — M. Hoffman.”

Woody Guthrie, I figured.

I was an ignorant 14 year old, but I knew who he was. Two years before, I was a junior high student in Fort Worth, Texas. There was a music-loving girl who sat next to me in Mrs Brock’s speech class. She was a non-stop talker and that spring, she was obsessed with Arlo Guthrie, who had just released his debut album, Alice’s Restaurant.

“He’s Woody’s son, you know.”

I nodded; she was cute and I pretended I knew more than I did.

Guthrie — was that the guy who wrote “This Land is Your Land”?

“You know, Woody died the same month Arlo’s album came out,” she said. I nodded again. “I hope Woody got to see Arlo’s album before he died.”

Nothing ever happened with that nice girl, due to my ineptitude with women. But she began to open me up musically.

The first album I ever bought — years before — was The Concert Sound of Henry Mancini. Thanks to that nice girl and her recommendations, by junior high I was beginning to listen to Simon & Garfunkel and a few other rock artists. I still had a lot of catching up to do if I wanted to be a card-carrying Baby Boomer.

Two years later, Texas in the rear-view, Ballad of Easy Rider came out (I refer to The Byrds album and not the Easy Rider soundtrack) and there, in a spot of honor near the end of the album was “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos).” Roger McGuinn, the head Byrd (and the only original band member left at that point) sang the song in his flat-tire matter-of-fact voice.

I was in better company by then. We’d moved to Bloomington, Indiana, and my classmates rated much higher on the hip meter than had my fellow scholars back at Monnig Junior High. [Though the cafeteria at that school served, every Monday, the best chicken-fried steak I’ve ever eaten. Also, our football coach, Spud Cason, was the inventor of the Wishbone offense.]

I began listening to a lot of stuff. I discovered Bob Dylan and Neil Young and Crosby, Stills and Nash. And, of course, The Byrds.

McGuinn sang “Deportee” in a somewhat neutral voice, and didn’t need to push any buttons to elicit a response. He wanted us to hear this story, which Guthrie had written as a poem, and he wanted us to feel. He did not want to feel for us.

His stark singing gave the song heart-breaking power. It was also in my vocal range. I think.

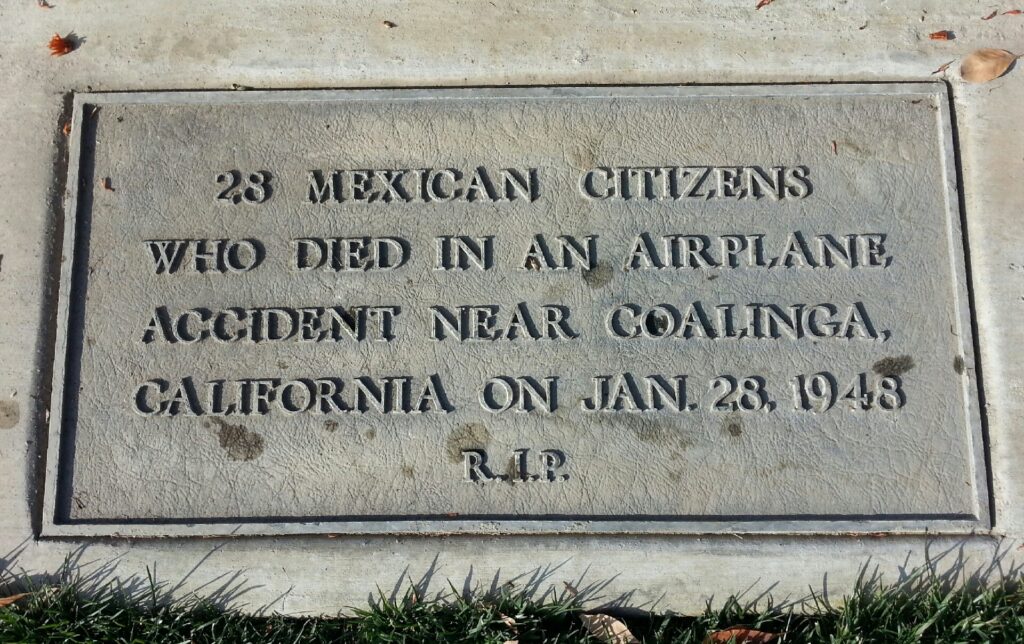

What we learned: a plane had crashed in a California canyon. In addition to the small flight crew, there were migrant workers on board, being deported to Mexico after the end of harvest. Without being told the story was true, we could tell this crash had really happened. Later, we’d learn that the plane caught fire and crashed on January 28, 1948.

There was a problem with a gasket in the left engine. As the plane lost altitude, it splintered into flame and the left wing fell off.

Witnesses to the crash said they saw some passengers jump from the plane before it hit the ground.

When Guthrie heard news of this on the radio, he was enraged by the off-hand way the announcer dismissed most of the passengers on the plane. As he told it:

The sky plane caught fire over Los Gatos Canyon,

A fireball of lightning, and shook all our hills,

Who are all these friends, all scattered like dry leaves?

The radio says, “They are just deportees”

Guthrie had long championed the cause of migrant workers. One of his best songs, in my mind, is “Pastures of Plenty.”

In the angry verses of that song, Guthrie spoke in the voice of farmworkers addressing those who lived off their backs and labor:

California, Arizona, I harvest your crops

Well it’s North up to Oregon to gather your hops

Dig the beets from your ground, cut the grapes from your vine

To set on your table your light sparkling wine

Further back in my musical history, I recalled third grade in South Florida, on the southernmost military installation on the mainland, during the Cuban Missile Crisis. (But that’s another story.)

When the denizens of Air Base Elementary congregated in the cafetorium, we sang Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” and other American songs, including the spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.”

When I was a kid, I’d hear rumblings now and then about “This Land is Your Land” becoming our new national anthem. Everybody, it seemed, hated “The Star Spangled Banner.” Me, I always liked it because we only sing one verse of the song at ballgames and it ends with a question we can ask ourselves every day: Are we still the land of the free and the home of the brave?

What I didn’t learn until much later was that “This Land is Your Land” was an angry answer song to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.” That uber-patriotic song infuriated Guthrie.

The original chorus to what became “This Land” was: “God blessed America for me.”

And, in another key verse, Guthrie may have been supplying a Marxist answer to Irving Berlin’s jingoism:

There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me.

The sign was painted, said ‘Private Property.’

But on the backside, it didn’t say nothing.

That side was made for you and me.

Some might say his songs were bitter, but to me they carried the fragrance of optimism. We can do this, we will endure. Those were the sentiments I took away.

Often attributed to Guthrie: “A folk song is what’s wrong and how to fix it.”

But then: “Deportee.” There was no optimism there, just human beings whose lives were devalued because of their skin color.

The passengers, the friends scattered like dry leaves, do not even earn the dignity of being known by name. They were “just deportees.”

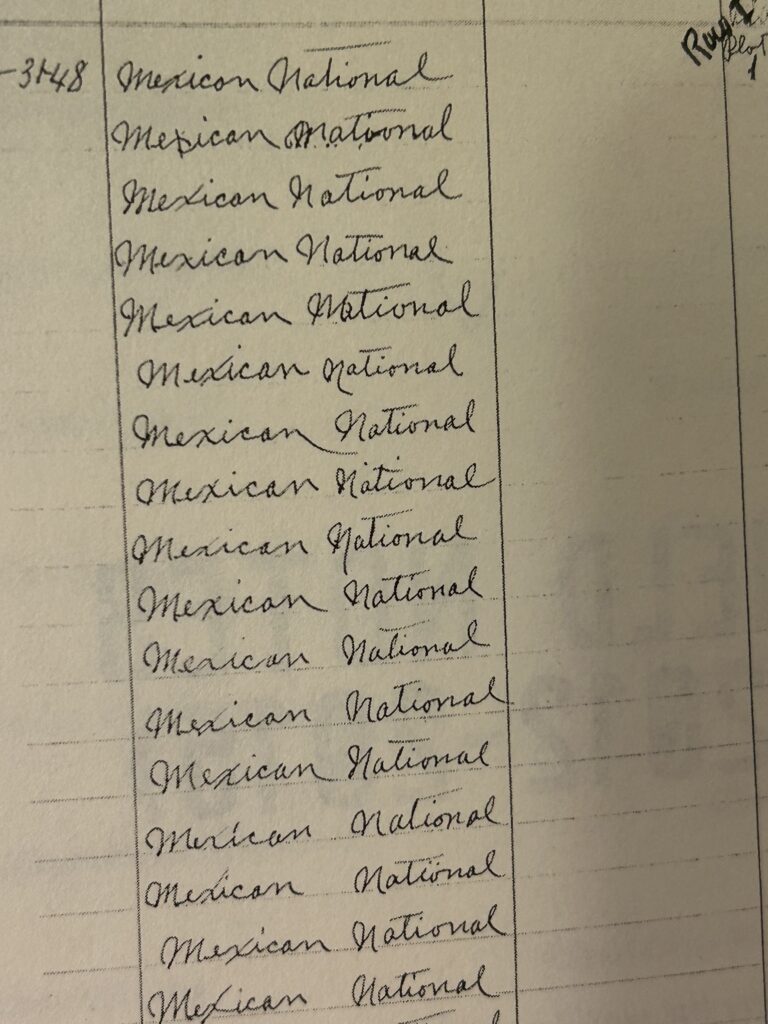

The plane’s manifest named the crew, but for passengers, they were listed as a group of “Mexican nationals.” The passengers were buried in a mass grave.

Demonize the immigrant, demonize the undocumented. It’s the American way. The more things change, they don’t.

Guthrie wrote the “Plane Wreck at Los Gatos” poem on his kitchen table, within hours after hearing of the crash. He didn’t write it as a song because he was beginning to lose his musical ability, as the degenerative neurological condition known as Huntington’s disease began its destruction of his body. He was beginning a long, slow decline that within a few years would leave him without his voice.

It took 20 years to kill him.

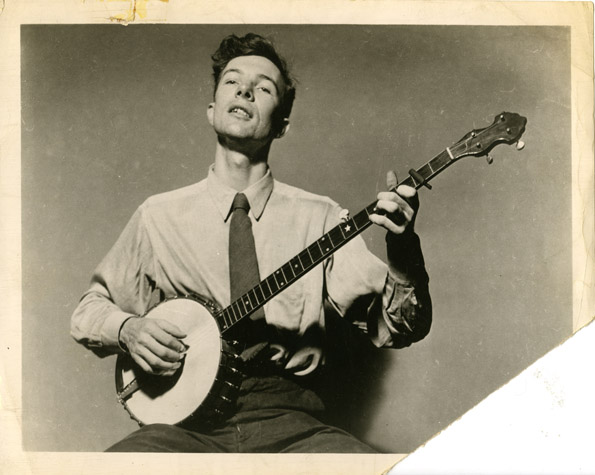

A decade after the crash, Pete Seeger was on a campus tour, singing the songs that had gotten him blacklisted during the McCarthy Era.

At Colorado A&M in Fort Collins, he did his show then gathered afterward at the home of a member of the college’s folk song club. Seeger played more songs, the students played some songs, and Seeger was about to fall into slumber on the couch, when one of the students — it was his living room — said he’d taken a poem of Guthrie’s, the one about the plane crash, and set it to music.

Martin Hoffman based his melody on a Mexican waltz, which made such sense with the words. Seeger listened as Hoffman sang “Deportee” but didn’t say much. He was tired.

But when Seeger got back to New York, he called Hoffman and asked him to send a tape of him singing the song, so he could get it copyrighted, with authorship split between Guthrie and Hoffman. That was 1958.

And then Seeger began performing the song. Judy Collins recorded it. Arlo Guthrie recorded it, as did Dolly Parton, Bruce Springsteen and Joan Baez. And so did The Byrds.

Recently, a 1948 recording of Guthrie talking / singing “Deportee” has been unearthed. He was losing his ability to sing, but he got through it. It was not long after the crash and he wanted to make sure his poem would live longer than he would.

Hearing that voice from 70 years ago, despite Guthrie’s pain and ravage, the song that began as a poem still has its power.

And the question returns: “Who are these friends who are scattered like dry leaves?”

It began with a poem, so it’s fitting that a poet answers the questions in the song.

Tim Z Hernandez is an associate professor in the creative writing program at the University of Texas at El Paso. He is a renaissance man, producing art in a variety of media.

Hearing “Deportee” had the effect on Hernandez that it had on me, but he did something about it. He set up a website to solicit donations to his project to make a documentary about the crash and the plane’s passengers.

He found out who those dry leaves were and he told their stories. No longer were they “just deportees.”

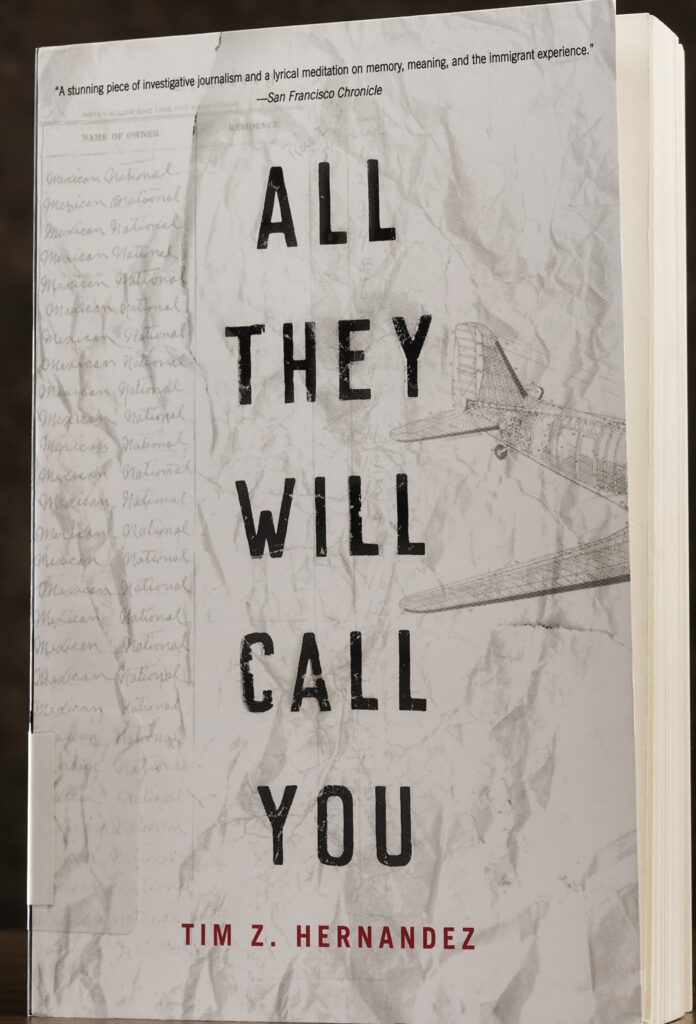

Hernandez produced an excellent and compelling book a few years back called All They Will Call You (University of Arizona Press, $13.35).

He deserves to add “historical researcher / journalist” to his list of talents.

Where the passengers had been listed a “Mexican Nationals” on the manifest, he now offered names and stories of the passengers — what their lives were like, what dreams they had, how their families carried on.

With his poet’s license, he indulges in speculation about the last moments on the plane, but he has researched the passengers enough to know them and his conjecture is not out of line.

Hernandez is transparent in the book, bringing readers into his interviewing process and gathering stories from descendants of the crash victims.

Across the decades, Hernandez answers the song’s question about the doomed passengers. Guthrie would approve of this other poet’s work.

Writer Joe Klein called “Deportee” Guthrie’s last great song before the disease crippled him. Guthrie recorded it with only the whisper of accompaniment, chanting the words, unable to sing as the disease began its torturous dance on his body.

The words waited a decade before they were found by Hoffman and his Mexican waltz, which gives the song its razor edge of tragedy and beauty.

One evening in 1971, Martin Hoffman walked through his neighborhood and knocked on doors, telling his friends how much he appreciated them.

Then he said goodbye.

The next evening, he played guitar, took a slug of Scotch, then went into his bedroom, pulled out his double-barrel shotgun from under the bed. He put the barrel square in front of his face, then pulled the trigger with his big toe.

The song leaves us another mystery.

With the grace and beauty of a poet, Hernandez tells the story of the passengers, the small crew, Guthrie’s life and work and Hoffman’s short and tragic time on earth.

I marvel at his achievement. The storytelling tribe can do great things, right past wrongs, and find the truth behind the stories.

If just for a moment, Hernandez brought those friends back to life, honoring them by giving us their names and telling their stories.

All They Will Call You is a beautiful piece of work.

The passengers: Ramon Perez, Jesus Santos, Ramon Portello, James A. Guardaho, Guadalupe Ramirez, Julio Barron, Jose Macias, Martin Navarro, Apolonio Placentia, Santiago Elisandro, Salvadore Sandoval, Manuel Calderon, Francisco Duran, Rosalio Estrado, Bernabe Garcia, Severo Lara, Elias Macias, Tomas Marquez, Louis Medina, Manuel Merino, Luis Mirando, Ygnacio Navarro, Roman Ochoa, Alberto Raygoza, Guadalupe Rodriquez, Maria Rodriguez, and Juan Ruiz. The pilot was Frank Atkinson and the co-pilot was Marion Ewing. Both Atkinson and Ewing were deeply experienced and flew with distinction in the Second World War. The regular flight attendant had called Atkinson that morning and said she was unable to fly. Bobbie Atkinson — the pilot’s wife, newly pregnant — said she would fill the flight-attendant role. She’d get to spend more time with her husband. There was another passenger: Frank E. Chaffin was with the Immigration and Naturalization Service. He was to escort the passengers back to Mexico. His job was to make certain the farmworkers got safely home.