The Back-Country Boy Genius

This was part of Prankster, a planned biography of Ken Kesey that never took off.

. . . . . . . . . .

Copyright © 2024 William McKeen

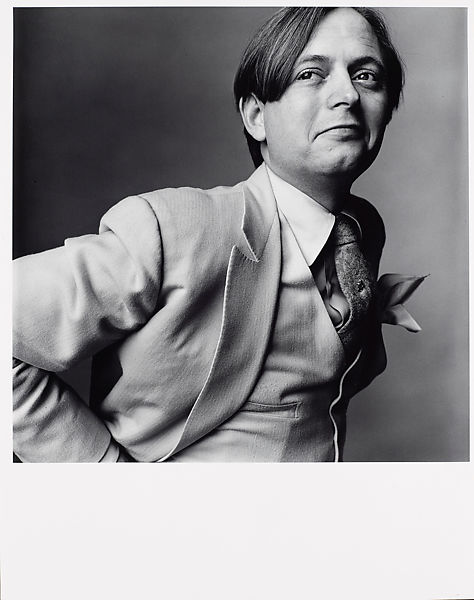

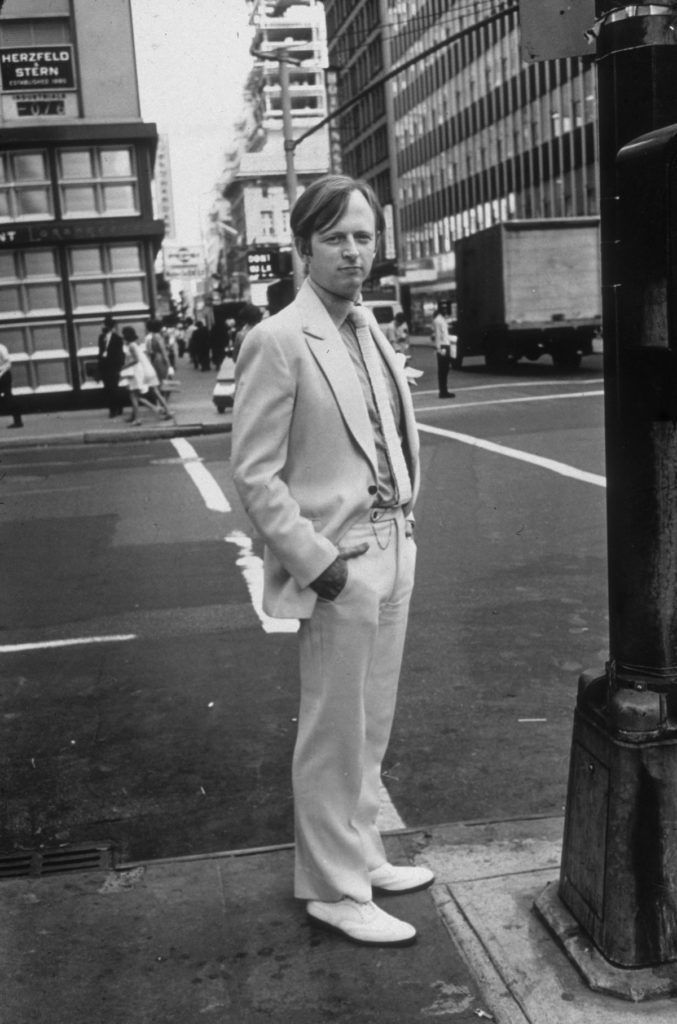

He stepped off the elevator and was suddenly in the waiting room; no hall, no doorway, no reception desk, no big-haired receptionist, nothing. Just right there in the waiting room with his new friends from the elevator. They wore jeans and untucked shirts and gave him the stink eye when he’d wedged in with them down in the lobby, as if he was the one absent of couth, and all because of his white suit. What’s so wrong about wearing a white suit in October?

When the elevator doors closed, his fellow traveler’s eyes narrowed as they stole — robbed, is more like it — glances at him, in his high, celluloid collar and spats. (Spats? Who outside of George Raft’s closet even owned spats anymore?) He’d caught their furtive what-the-fuck eyeballs in the elevator and, like any good son of the South, he smiled politely. He got a couple pained grimaces in return, then all eyes returned to the numbers above the elevator doors, all hoping, perhaps, that the numerals would rearrange themselves.

His elevator pals dumped him when the doors opened on the third floor, and the man in the white suit was left on his own, as the others scurried by him and scattered across the worn linoleum. They knew the drill; they weren’t rookies here at the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office in Redwood City, California, on this fine autumn day in 1966. Tom Wolfe was the lone San Mateo rookie that afternoon and as he got his bearings – which always included adjusting his cuffs and collar — the others walked up to their side of the booths where their fathers / boyfriends / sons awaited behind thick glass, phones already at their ears. The children / girlfriends / mothers sat down, picked up their phone on their side of the glass and began their jabber, much of it in adrenalized Spanish.

At first, Wolfe wondered if he’d be able to hear over the din — at least well enough to take notes. That was his job, after all. He was here as a professional journalist, looking for a story to tell, and for a moment, he’d been so concerned about these logistics and the volume level that he didn’t realize that the man he came to see was standing opposite him, back against the far wall, looking through the triple-thick glass at the over-dressed writer.

The man stood there, arms crossed over his ridiculously burly chest, staring at Wolfe – or was it through Wolfe? His resolute eyes drilled holes in the concrete over Wolfe’s shoulder and he appeared to be made of that same substance, this Superman with X-Ray eyes. He acknowledged Wolfe with a languid, lizard-like blink, and that was when Wolfe first laid orbs on Ken Kesey.

Kesey was in the pokey for marijuana possession, his second bust. After this latest pinch, he’d gone missing and the word back in New York, where Wolfe was one of the leading shakespeares of American journalism, was that he had gone undercover in Mexico. Writing was such a sedentary act and so much sedentary time behind typewriters, that Wolfe found it pretty exciting that one of his tribe should light out on his own, into the wilderness, becoming a fugitive from the law. A writer … actually doing something interesting, off the keister and daring.

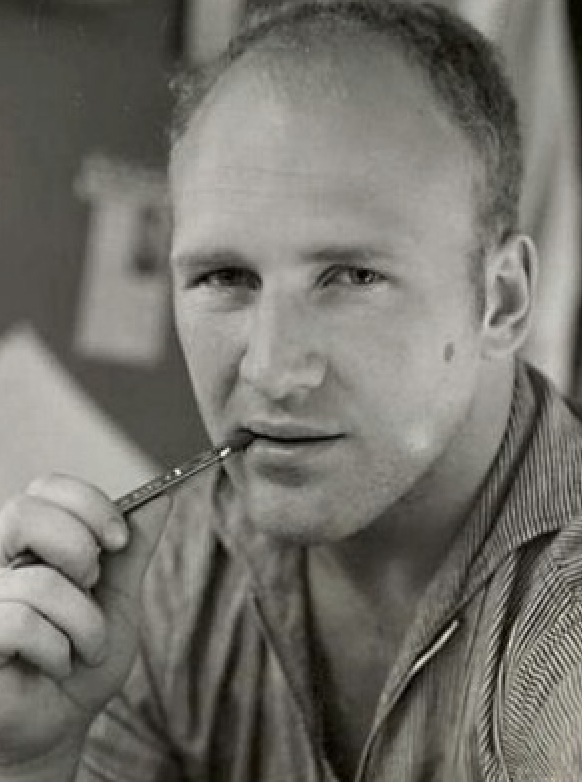

And it was Ken Kesey. If anyone would seem to have it going on at that point in the history of American life and letters, it would be Kesey. He’d come out of the University of Oregon as a star athlete and scholar, a writing wunderkind, and settled down right away to become a junior-varsity Hemingway. If anyone else could come close to the old man as a Great American Writer, it might be this golden-jock country boy from Oregon.

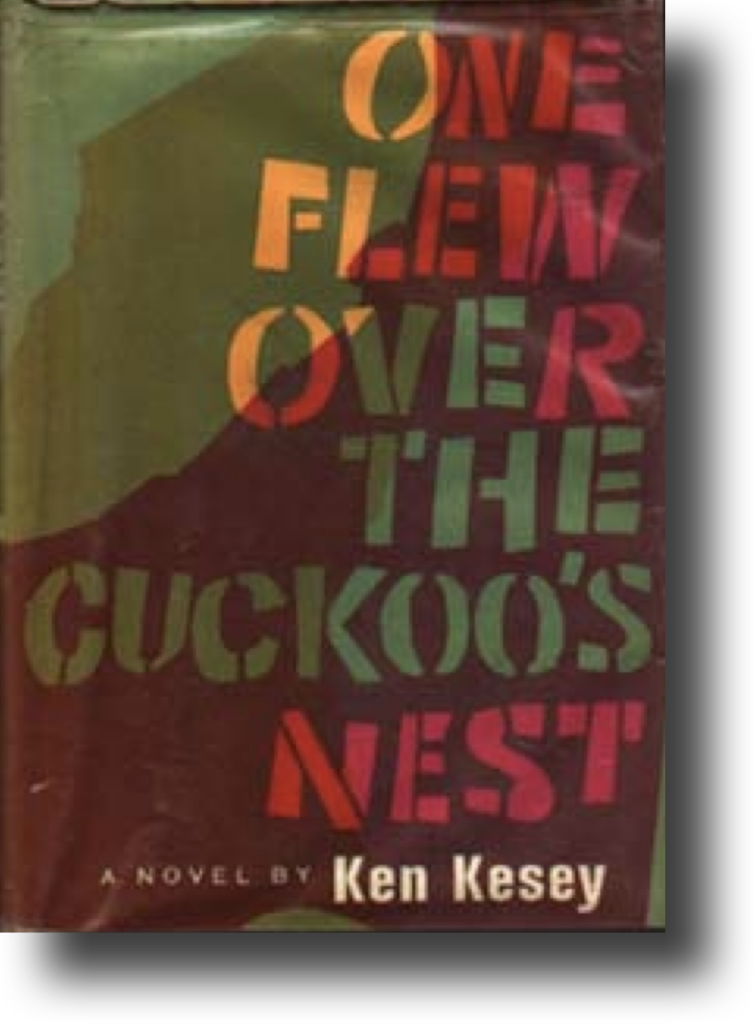

Right out of the block, he published One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (in 1962) and then, two years later, Sometimes a Great Notion. That one-two punch made it clear his apprenticeship was over and he was ready for his closeup. He’d made the varsity.

But then. Yes … but then. Then came the bus trip, the drugs, the parties, the affairs, the goddam rock’n’roll, the bust, then the writer-on-the-lam in Mexico, then the writer in the San Mateo County Jail.

Ken Kesey, man of great literary promise, had it all but was pissing it away and now here he was, across the glass from Wolfe, big and burly, 31 years old and in deep shit. But a smile shadowed his face and he did not act like a man in deep shit. His face said I got it by the balls, and Wolfe realized he probably did.

Tom Wolfe loved stories of class and status and mislaid dreams. Face to face with his subject, he was thinking, this is a hell of a story. You had it all, Kesey. Wasn’t that enough for you?

They were from opposite sides of the country, these two. At that moment in the jail, they were down the coast from Kesey’s stomping grounds in Oregon, where he became known as a backcountry boy genius. But he’d been born, mid-Depression, in rural Colorado, in a little village that was once the trading post where the Santa Fe Trail split into northern and southern routes. La Junta was scattered along a southward bend of the Arkansas River, 60 miles east of Pueblo, and a 130-mile razor-straight shot west of Holcomb, Kansas, in bone-flat Eastern Colorado.

That part of the state was indistinguishable from the monotony of the west Kansas plains. Never much of a town to begin with (it flirted with a 10,000 population, never quite making it), it became even less so during the Depression, and then the primary crop thereabouts — sugar beets — was slowly replaced by corn syrup as a sweetener in processed foods. The town eventually earned a listing in the Encyclopedia of Forlorn Places.

Fred and Geneva Kesey gave up on La Junta in 1941 and moved their small family cross country, eventually settling near Springfield, Oregon, when oldest son Ken was eleven. Fred Kesey established a business to serve fellow dairy farmers and fortunes began to improve in time for Ken and younger brother Chuck to enjoy a golden childhood in the American West.

Springfield, on the mirror-like McKenzie River, was a prime spot for rainbow trout, in unspoiled forests on the verge of the Cascades. The looming mountains reminded the Kesey boys they weren’t in the flat plains anymore. Ken and his brothers swam in ponds and rivers, caught fish, played every sport imaginable. Ken emerged as the golden jock, a star athlete at Springfield High School. He was a lineman on the football team and an exceptional wrestler in the 174-pound class.

Though he set high school wrestling records, it was as a football player that Kesey earned a scholarship to the University of Oregon, picking journalism for his major and diligently turning in class assignments and working on the school newspaper. Along the way, he married Norma Haxby — they called her Faye — his high school sweetheart.

He seemed ready to begin his career as an ace reporter when another kind of writing beckoned. The journalism had shown him that he had the gift of lucidity and now he turned it toward the writing of fiction. Before long, he’d earned a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship at Stanford, and he was veering sharply away from the simple-farm-boy’s course.

He was then deep in the bohemian world of graduate school and long talks about Great Things, punctuated by marijuana. Then, as a surprise out of left field — courtesy of the Central Intelligence Agency — came offers to experiment with lysergic acid diethylamide, soon to be known and beloved as LSD. The agency was researching the posibility of using acid as some sort of weapon, so they tested it out of the perpetually needy population of graduate students. Maybe it was a weapon, but not the way the spooks at Langley thought of it. Kesey saw it as a weapon too, but of a different kind. It would be a great tool in his fight against emotional faciscm.

After LSD, Kesey was never quite the same.

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe, Jr., came from the opposite side of the country, from the former capital of the Confederate States of America: Richmond, Virginia. That went part of the way toward explaining the white suit. Young Southern gentlemen were practically issued the things, but that wasn’t the only reason he wore them.

At an autumn lawn party on Long Island, not long after he’d landed in New York in 1962, Wolfe was rifling through his closet, trying to figure out what to wear for this Sunday afternoon get-together. He discovered only one clean suit, the trusty old white one.

So he wore it to the party. As he passed through the house, picking up a cocktail, he stepped into the back yard and could immediately feel the eyeballs on him. The other guests kept their distance and the harumphers stopped harumphing. He was aware that they were watching him.

Still, he made his way across the lawn, not certain what was going on, until one old crone approached him, her cocktail shaking in her tremblng hand, and said, “How dare you!”

Of course! White after Labor Day! How gauche!

Wolfe could not have been more pleased. He hadn’t said a word, yet pissed off not only this hummocky old woman, but also the rest of the crowd.

He thought: I didn’t even open my mouth, and they are furious. He loved to piss off people. The next week, he went to a tailor in Manhattan to have white suits made in every style and fabric so he could piss off people no matter what the season. Clothing was, he often said, “harmless aggression.”

He’d started as something less than a dandy. His father was an academic and editor of a scholarly agricultural journal called The Southern Planter. To young Tom, this made his father a Serious Writer and that was something he admired from an early age. His mother made sure he was exposed to the arts, but young Tom didn’t mince around the house in leotards. He took part in all the usual masculine activities, becoming in his own way something of a jock. He was good enough to earn a tryout as a pitcher at the New York Giants’ spring training camp, but he blew out his arm and was sent home.

At Washington and Lee University he majored in American Studies under Professor Marshall Fishwick, who had an unusual approach to his subject, a hybrid of literature and history. To learn about America, Fishwick told his students, we must be out in it. So they learned masonry and worked construction one week, then carried garbage the next, to understand the country from the bottom of the social order to the top.

After the brief and failed stop with the Giants, Wolfe headed off to Yale’s doctoral program in American Studies, where he focused on the meaning of class and status in modern (1950s) life. The world had been turned upside down. Wolfe observed that to publish something that resonated and affected a lot of people was to fail in the minds of the intelligentsia. True success and academic status was instead earned by reaching a microscopic, elite audience.

After finishing his course work, Wolfe left school to work while completing his dissertation. After so much schooling, he longed for the real life, so he got a job delivering office furniture and — it being the late 1950s — he dressed in the cool-guy wardrobe of the time: beatnik black. He thought he’d meet some girls while carrying furniture around offices but soon discovered that his physical efforts left him sweaty and ripe and decidedly unattractive.

So he fell into a cave of ice: the dissertation mouldered on the kitchen table in his tiny apartment and he lounged on his sofa, steeping in his rank juices, drinking beer and watching television until he passed out.

But then there it was on the late show: His Girl Friday, the classic newspaper movie with Cary Grant as the hard-charging newspaper editor and Rosalind Russell as his star reporter (and ex-wife) Hildy Johnson. Wolfe fell in love. That looks like fun, he thought. That’s what I want to do.

He finished off his dissertation and with his doctorate in hand, applied to 153 newspapers, assuming that all of them would want to have someone with a PhD on the staff.

He got no response. Oh, he was offered one job — as a copy boy on the New York Post. But when he heard some editors through the wall joking about their PhD copy boy, he realized he would just be a gag.

Eventually, he got a reporting job on the Springfield Republican in Massachusetts, where he covered — among hearings on sewage treatment and utility rate hikes — the rise of Senator John Kennedy as a serious presidential condender.

After a couple of years there, he was hired by the Washington Post. It was not yet the great, president-toppling newspaper it would become and was, in fact, something of a mess. I.F. Stone once said of the Post in that era, “It’s an exciting paper to read because you never know on what page you will find a page-one story.”

The Post had no idea what to do with Wolfe, who already was showing a skewed and screwy way of looking at the world.

By 1962, Wolfe had arrived at the premier writer’s paper in New York, the Herald Tribune. Finally, he thought, he was in the real world. He looked around the newsroom and saw some of the best and the brightest minds of his generation. And they weren’t all closet novelists, using journalism to pay the bills while they worked on the Great American Novel, stashed in the bottom desk drawer. These people weren’t using journalism as the means to an end. It was the end.

He soon became a national figure when he began moonlighting for Esquire magazine, the great cultural chronicle of the time. He went to cover a custom car rally in California — his big break for Esquire — and when he got back to New York he faced a writer’s block the size of K-2. When managing editor Byron Dobell called up with his where-is-it question, Wolfe had to tell him he couldn’t write the damn thing.

Okay, Dobell told Wolfe. Type up your notes and send them over. We’ll have someone else write the story.

So Wolfe sat down that night and spewed out a 49-page memo that began “Dear Byron,” and continued to offer stream-of-consciousness observations about the car-customizing subculture in California. He finished the memo at six in the morning, showered and shaved, and dropped it off at Esquire before going to work at the Herald Tribune.

Byron Dobell called that afternoon. He’d crossed out two words — “Dear Byron” — and was running the rest of the memo, uncut, in the next issue of Esquire. Tom Wolfe and what was in that time known as “new journalism” had arrived.

Wolfe’s style could clear a room. Filled with sound effects, tourette’s-like ejaculations and odd, outer-space punctuation, his pieces fell into the love or hate piles. There was no in-between. He soon developed a following and by 1965 published his first book, a collection of magazine articles called The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.

And then, one day in 1966, some letters came across his desk at the Herald Tribune. A young writer named Larry McMurtry — at that point, principally known as the author of the source book for the Paul Newman film Hud — sent them to Wolfe because he thought there was a good story in the correspondence.

And there was. There were two letters, both written to McMurtry by Ken Kesey. The name rang a bell with Wolfe — oh yes, that Cuckoo’s Nest fellow. As Wolfe read the letters, he was drawn in. Kesey had gotten into some trouble with the California authorities and he was now, according to the letters, on the lam.

Wolfe thought in headlines: FUGITIVE NOVELIST ON THE RUN IN MEXICO. He talked to his two great editors and mentors — Clay Felker at the Herald Tribune’s Sunday magazine, New York, and Harold Hayes, the visionary at Esquire. Both encouraged him to prusue the story. Just as he was booking his flight to Mexico City, where he planned to go find this fugitive novelist, Kesey was captured. He was being transported back to California.

And now, here we was, on the other side of the glass.

Wolfe was full of questions, but he had only a matter of minutes. He was still driven by the fugitive-novelist narrative but he could tell Kesey had clearly moved on. He was beyond that; far beyond that.

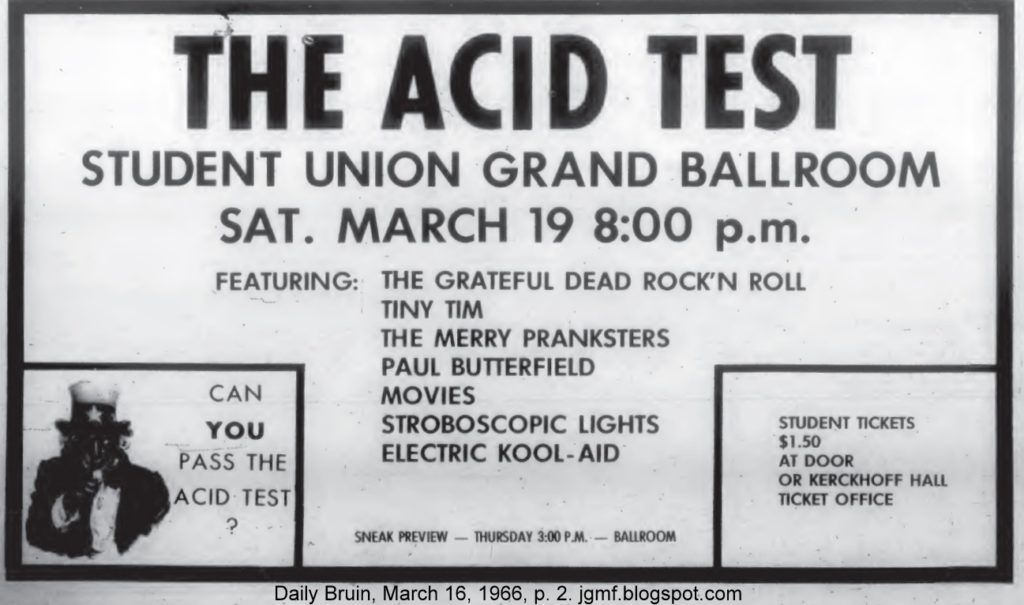

In those days after his experiences with LSD, Kesey had become some kind of high priest of acid and had even led a bunch of … well, there was no other word for them … freaks on a coast-to-coast ramble in an old school bus painted all kinds of goddam colors. And he was preaching the gospel of acid and having parties called acid tests with all kinds of godawful rock’n’roll music.

So Wolfe thought, as he held his phone to his ear and watched Kesey, phone to his ear, but scant inches away, what about that.

But he wasn’t finished asking the acid question when he could tell Kesey was as bored as if he was watching a rerun of seventh grade math class.

Kesey spoke patiently in his country-boy drawl, sounding six thousand miles away through the tinny connection, instead of six inches through the glass.

“It’s my idea that it’s time to graduate from what has been going on, to something else,” he said matter of factly. “The psychedlic wave was happening six or eight months ago when I went to Mexico. It’s been growing since then, but it hasn’t been moving. I saw the same stuff when I got back as when I left. It was just bigger, that was all. There’s been no creativity and I thnk my value has been to help create the next step.”

He speaks slowly, as if Tom Wolfe, PhD, was a dim-bulb child. “I don’t think there will be any movement off the drug scene until there is something else to move to.”

Wolfe, taking notes and nodding, had no idea what this guy was talking about. Is he out of his mind?

“I heard you don’t intend to do any more writing,” Wolfe said, moving back to the narrative he’d planted and feritilized in his skull. “Why?”

Kesey smiled. “I’d rather be a lightning rod than a seismograph,” he said slowly.

Then Kesey was back talking about these “acid tests” he planned and how there would be no distance, no separation, between himself and the audience. And to Wolfe it was more stone gibberish. That’s it, he thought, this man is bonkers. Kesey talked about what these events would be and what form they would take.

Wolfe saw an opening, a way to bring the story back to a recognizable narrative for a hot-shot journalist from New York City.

“Oh, you mean something on the order of what Andy Warhol is doing?” he suggested.

The slow-burn smile was back on Kesey’s face. “No offense,” he said, talking to the dim bulb again, “but New York is about two years behind.”

Touche, you New York motherfucker!

The guards came along and hustled the visitors out to tearful goodbyes and kisses pressed to the glass.

Kesey hung up and stood, showing his fatherly patient smile. Wolfe rose and nodded, wondering what the hell he had gotten into and what the hell was the deal with this Kesey fellow.

“I had gotten nothing,” Wolfe recalled, “except my first brush wth a strange phenomenon, that strange up-country charisma, the Kesey presence.”