Eight Miles High

Here’s a little bit from a planned project on The Byrds, one of my favorite bands, and a band that I don’t think gets as much attention as it deserves. This was to be the first chapter.

. . . . . . . . . .

Copyright © 2025 William McKeen

Funny how they vibrate. He watched, absorbed, as the string throbbed, slipping from a blur back to its finite shape. A haze, a mere impression, slowly pulling back to become taut filament. Then again, with the thumb, and the deep, rich tone of the Martin resonated. He wanted to crawl inside the guitar and wrap himself up in the rich blanket of its sound. Once more, the thumb pulled the nylon string. Sharp, piercing, then . . . flattening out. He cocked his ear and listened as its firm note faded and receded back to silence.

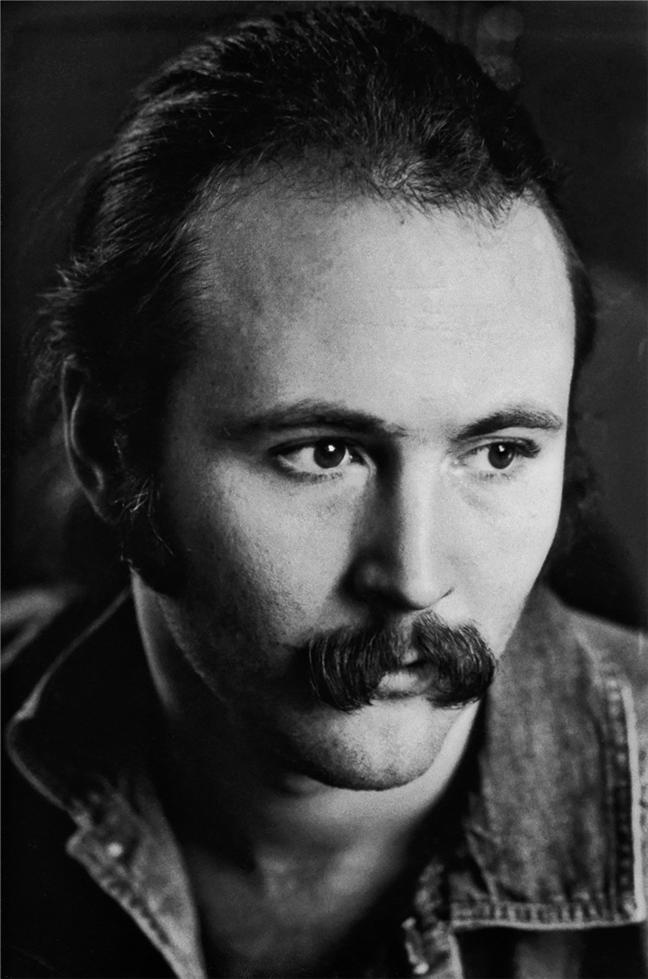

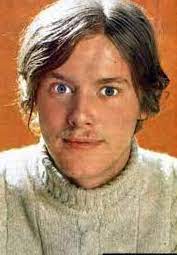

As he beheld his view from his perch overlooking Beverly Glen Canyon, David Crosby – rock’n’roll star, citizen of the world, and, at that moment, thoroughly stoned human being – fixated on the sound emanating from his acoustic guitar and pondered his place in the world.

Where exactly was that place? He was here, in the living room of his house in Los Angeles. This was home, where he roared through the streets in his Porsche, drank from the trough of rock-star fame, and where he strode around the living room with with two – sometimes three – naked young women in tow. Croz had the world by the balls. This was the American Dream. Fuck Horatio Alger. Fuck the idea of a girl in every port. That was amateur hour. He had a girl in every room. In so many ways, David Crosby’s world seemed perfect in September 1967.

Perfect until it wasn’t. He was alone now, but it wasn’t the absence of his usual gaggle of young nubiles that had him dull and contemplative on this late-summer afternoon in Southern California. He was steeped in despair, as if a long love affair was unraveling and he was trapped in the miasma of lost romance and unquenched desire. But it wasn’t with a woman, this affair. It was with his livelihood, his raison d’être, his joy, his platform . . . his rock’n’roll band, The Byrds.

The band was breaking his heart. He knew what he wanted, and sometimes it seemed that the other guys wanted something completely at odds. It had gotten to the point where if Croz was for something, the other guys were against it, just because.

They’d started out three years before – a geologic age in the ash-heap world of popular music – as five. One left and the others carried on, but with less joy. With five of them, there had been arguments and power struggles and constant conflict. But something magic rose from the ashes of incendiary sparring. The fire of back-and-forth had produced some of the greatest and most meaningful music of the decade.

But then Gene Clark left. That had been the first ending.

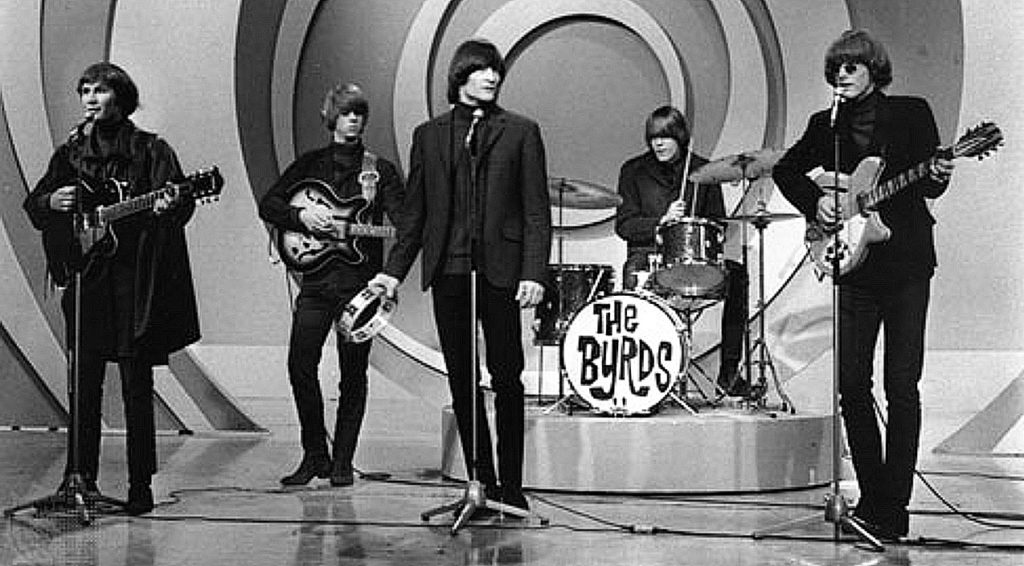

The Byrds had been “America’s answer to the Beatles,” back in 1965, when such a thing was needed. The year before, Crosby had been drifting around Los Angeles when he reconnected with Greenwich Village folkie Jim McGuinn.

McGuinn and this long, lanky fellow named Gene Clark started playing acoustic Beatle songs in the entry way of the Troubadour on Sunset. Iron-jawed and magnetic, Clark was pure cornpone from Bonner Springs, Kansas. Crosby liked what he heard and asked to sing. Clark was game, but McGuinn knew Crosby and thought he was a gold-plated asshole. McGuinn was hesitant, but then he heard what they sounded like together.

Crosby made them a trio and after seeing the Beatles romp onscreen in A Hard Day’s Night, the trio decided to become a rock band. Feeling it their patriotic duty to reclaim the American art form of rock’n’roll from the Beatles and scores of other Brits, they found a rhythm section and tried to meld their five personalities into one coherent unit. They came up with the name Byrds, using the Y to be kind of a British thing and kind of a Bob Dylan thing.

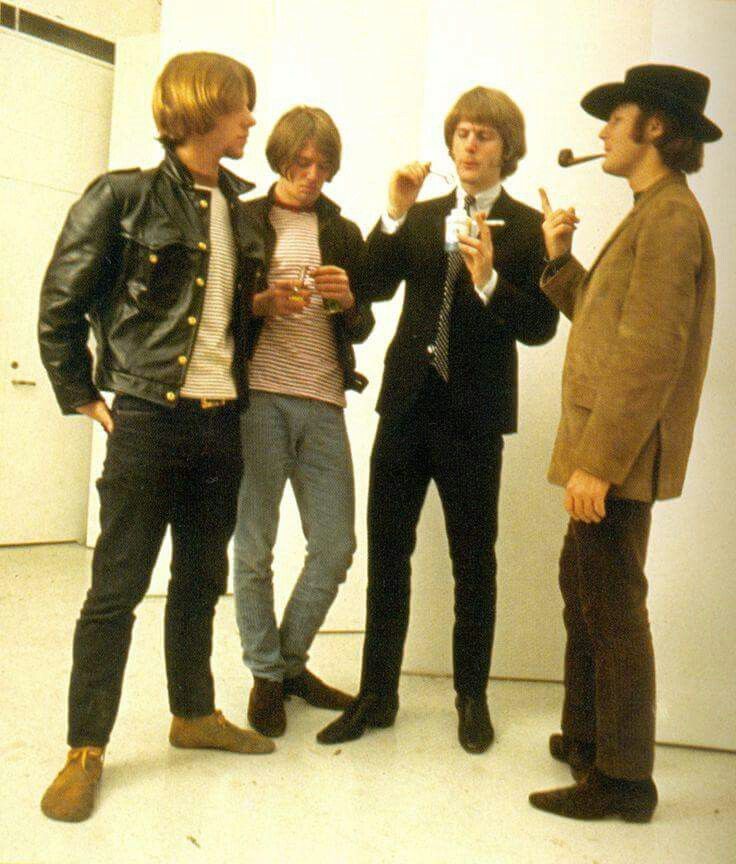

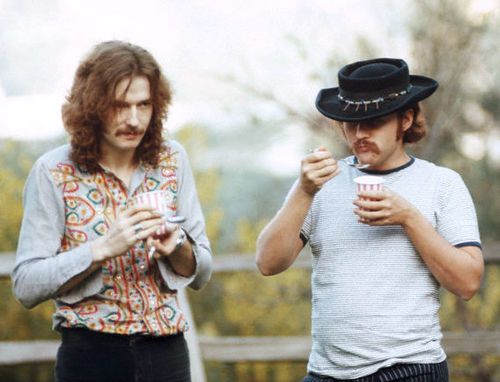

Success didn’t happen over night and there was a lot of fighting from the start. Crosby and McGuinn butted heads constantly. They’d never much liked each other, but saw advantages in pooling their talent. Then there was their bass player who wasn’t a bass player. Chris Hillman was a bluegrass guy, a mandolin prodigy, dragged into the band by the fledgling group’s manager. And then there was Michael Clarke – Dick was his real last name (and so appropriate, Croz thought) – who’d been hired because he had cool Brian Jones hair and looked like a drummer.

In short, the Byrds were a mess. But thanks to that Dylan guy and an early acetate of his song “Mr. Tambourine Man,” in the spring of 1965, the Byrds got Dylan to number one before Dylan got himself to number one. The Byrds were harbingers of a new genre, called Folk Rock by the wags, and seemed to promise a new, smarter kind of rock’n’roll. America’s answer to the Beatles. Take that, you British swine.

But that was so long ago—two years, an eternity in the modern world. So now Crosby sat, stoned, plucking his guitar, wondering where he was going, and if he was going there with his band.

And that’s when he heard the engines in the driveway. He looked up and there they were: twin Porsches. McGuinn and Hillman got out of their cars and slowly started up the walk toward Crosby’s front door.

Back in 1965, Crosby hadn’t wanted to ride the Dylan coattails. He thought the guy was overrated anyway. He’d spent some time in the Village and did a stint as part of a pansy-ass faux folk group called Les Baxter’s Balladeers and was known onstage as L’il David. To Crosby, Dylan was just a guy who wrapped up a lot of music traditions and repackaged them in hipper, contemporary language. He’d just gotten lucky. Crosby stewed because he figured he could have been That Guy. He also stewed because he was stuck in some show-biz schlockmeister’s concept of folk music for the masses. He hated Les Baxter’s Balladeers and he really fucking hated being L’il David.

When Crosby had been out on those awful road trips with the Balladeers, freezing his ass off on the back of the tour bus, he’d hear the other performers and the audiences buzzing about this Dylan guy. The great new face of folk music. He’s a phony, Crosby would grumble. He’s no better than me; he just got lucky.

But the Dylan stuff didn’t go away and even though he wasn’t selling records by the truckload, his influence was felt. Every step of Dylan’s ascendancy was like a railroad spike in Crosby’s spine. So when he and McGuinn and the others formed a band and their manager said, Hey, I got an acetate of this cool new Dylan song, Crosby did not get a hard-on about recording it. So what, he told his bandmates, we can write our own songs.

But they recorded “Mr. Tambourine Man,” releasing it the same spring that Dylan finally put it on an album, as an acoustic track on the back side of Bringing it All Back Home. Six verses in all, sung by its composer with a majesty that belied no interest in cow-towing to the conventions of American popular music. The Byrds weren’t Dylan, however, and so they cow-towed. Their arrangement cut the song down to chorus / verse (the second one) / chorus. In and out in two minutes and 16 seconds.

That was the beginning of rock stardom for David Crosby and the rest of the Byrds. So now here he was in Beverly Glen Canyon, with his guitars and his women in every room — except that he was alone now and knew, from engine roar and tire squeal that two other Byrds were coming to his door.

It had been tense. Crosby knew that and knew he was the cause. There had always been trouble, but if Crosby wanted to pinpoint where the latest run of anger came from, it started a couple months before, up in Monterrey.

The Monterrey International Pop Festival, back in June, was a meeting of the cultures: the Los Angeles rock’n’roll community went north to meet the San Francisco bands nearer their home turf. It was a quintessential peace-love-and-flowers moment and should have been a high point for the Byrds. By 1967, with four fine albums and two number-one singles, they had achieved elder-statesmen status in rock music.

But then Crosby opened his mouth. Just as the band was about to sing McGuinn’s rewrite of “He Was a Friend of Mine,” which had been turned into a tribute to the late president, John F. Kennedy, Crosby — wearing a Cossack hat to cover his eroding hair-line — addressed the crowd.

“They’re shooting this for television,” he announced. Indeed, the stage was crawling with camera operators. “I’m sure they’re going to edit this out,” Crosby continued. “I want to say it anyway, even though they will edit it out. When President Kennedy was killed, he was not killed by one man. He was shot from a number of different directions, by different guns. The story has been suppressed, witnesses have been killed, and this is your country, ladies and gentlemen.”

McGuinn was visibly furious. Not the time or place, Croz, he said with his withering glare. But then they leaned in and sang into the same microphone, and the song rarely sounded better. Anger somehow brought out harmony.

But Crosby wasn’t through. When the song ended, he told the crowd: “As I say, they will censor it I’m sure. They can’t afford to have things like that on the air. It’d blow their image.”

Crosby also encouraged the crowd to give LSD a try, if they hadn’t already, and handled most of the “host” duties for the band. McGuinn, the group’s nominal leader, was not amused. Crosby was right about one thing: because of his rants (and a relatively lackluster performance), the Byrds were not featured in televised coverage of the festival or the marvelous D. A. Pennebaker documentary Monterey Pop.

On the festival’s next night, Crosby committed musical adultery, further infuriating his bandmates. He performed with Buffalo Springfield, which was down one member — guitarist Neil Young — because he was feuding with Stephen Stills, another guitarist in the group.

McGuinn watched the performance, anger building. Crosby hadn’t said a word about appearing onstage with another group and now came this public humiliation.

There had been rumors before, about Crosby going to San Francisco to hang out with the bands there, who carried themselves with a hipper-than-thou attitude. A lot of those groups — Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, the Electric Flag — looked down on the L.A. groups as being merely showbiz. Watching Croz onstage with the Springfield made McGuinn realize the rumors were true. It was like watching a lover giving deep tissue massage to a neighbor.

And then there was Crosby’s music. He thought he was avant garde and cutting edge, but McGuinn just thought he was boring. Their last album, Younger than Yesterday, was a tour de force that included some of the group’s finest songwriting. Since Gene Clark had left, the renegade mandolin player Chris Hillman had stepped to the plate as a songwriter and singer and made massive career-changing contributions. Crosby did too, but he also had “Mind Gardens,” his attempt at being avant garde.

“Mind Gardens” was so bad that to call it a piece of shit was an insult to pieces of shit. McGuinn and Hillman tried to talk him out of putting it on the album, but Crosby was determined. And so there it lay, a festering turd on side two of the magnificent Younger than Yesterday. All across the country, the cognoscenti of rock’n’roll lifted the needle after “Thoughts and Words,” skipped the festering turd, and put the needle back down for “My Back Pages.”

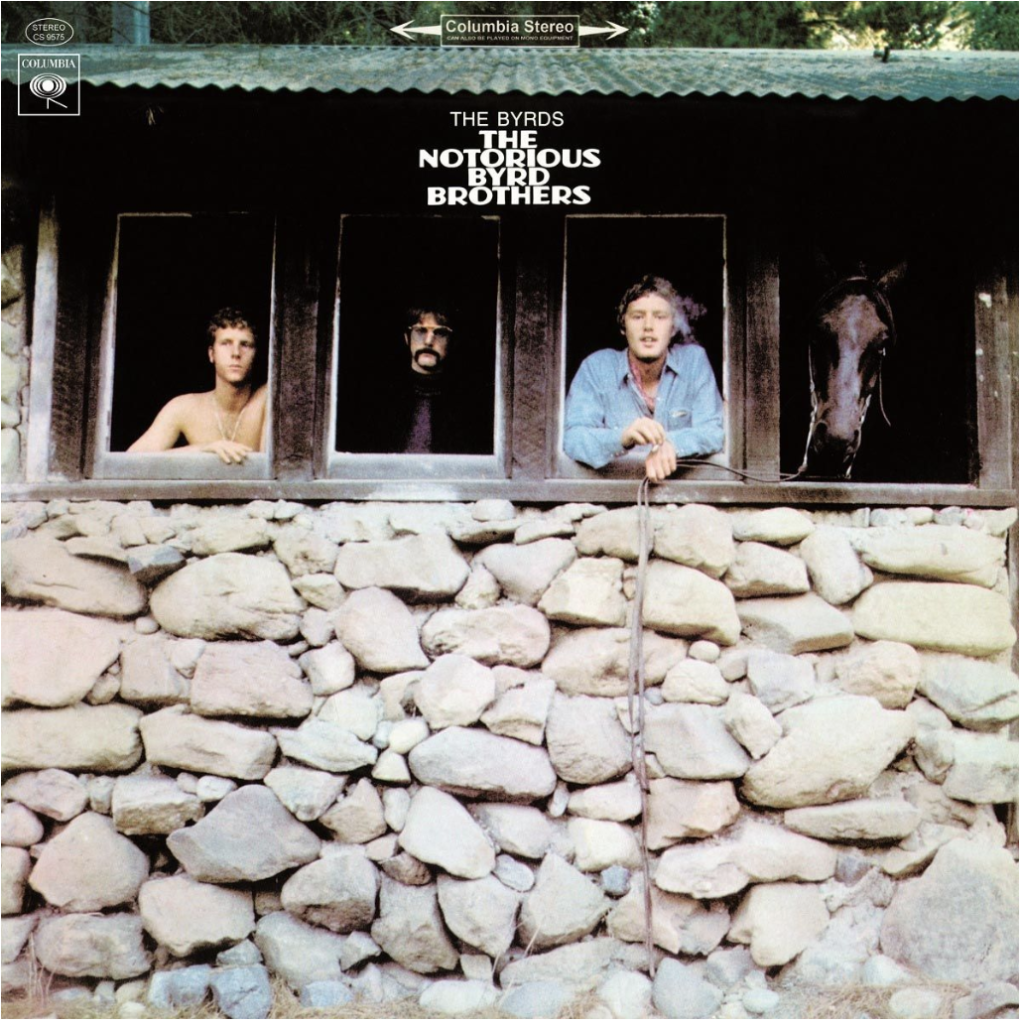

But “Mind Gardens” was just the beginning. Now, in the waning days of late summer 1967, the Byrds were at work on their fifth album and Crosby was in full irritant mode in the studio, insinuating his opinion was the only one that mattered.

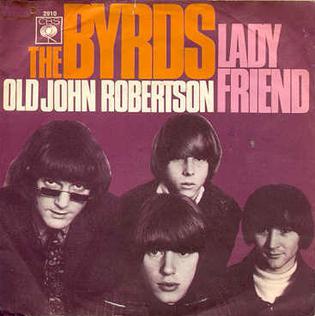

The summer single from the group was “Lady Friend,” a Crosby composition featuring vigorous vocal and brass harmonics. The group’s voices had not been good enough for Crosby, however, so he had producer Gary Usher erase the other Byrds from the track and multitrack his voice. The result was a beautiful piece of music that inspired yawns among consumers. It staggered to number eighty-two on Billboard’s chart. (The single’s flip side for the British market was “Don’t Make Waves,” a McGuinn-Hillman composition for a film of the same title, starring Sharon Tate and Tony Curtis. At the end of the song, Crosby offered a sarcastic on-microphone comment: “Another masterpiece.” The smirk was cut before release.)

From the start of the sessions for the new album that summer, Crosby was at Michael Clarke’s throat. He’d never been satisfied with Clarke’s drumming, considering him a belt notch above an amateur.

Crosby argued over everything. He was most opposed to recording songs from outside composers. The Byrds chose to do “Goin’ Back,” a beautiful song of childhood recollection from songwriting veterans Gerry Goffin and Carole King. Fearing that inclusion of a Tin Pan Alley tune might keep one of his songs off the album, Crosby boycotted the track, refusing to sing on it. McGuinn recorded the song and it became one of the Byrds’ most beautiful performances.

It was 1967, the year when — as McGuinn said — musicians “were all trying to out-weird each other.” The Beatles set the standard with the studio whiz-bang effects of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and even groups that should have known better—the Rolling Stones being the primary example with Their Satanic Majesties Request—jumped into the spacey, flower power studio trickery. No one pulled it off as well as the Beatles.

But the album the Byrds were fighting over would be one of the finest of the 1967 weirdness competition. When not insulting each other, Crosby, McGuinn, and Hillman wrote terrific songs and sang exquisitely.

Then Crosby brought in a new song to record called “Triad,” an enthusiastic endorsement of group sex. The group recorded it, McGuinn and Hillman pulling a Crosby and not singing on the track. It just wasn’t right for the band, McGuinn and Hillman argued. But Croz was adamant.

Out of the group’s continuing dysfunction came other songs, including the anti-war “Draft Morning” (complete with battlefield sound effects); “Dolphins Smile,” one of Crosby’s jazziest and most lyrical songs; and a McGuinn science fiction epic called “Space Odyssey.”

As the four Byrds worked on “Dolphins Smile” at Columbia Recording Studios on August 14, Crosby’s frustration with Clarke’s clumsy playing boiled over, though the fight started meekly enough.

“Michael? Uh, can you,” Crosby began, trying to get the best work from Clarke that he could. He considered, then backed up and started over. “Maybe I’m not right. . . . If you really wanted to, you could really do it.”

“You mean the first time I ever play it?”

“Ah, sure man,” Crosby said. “I’ve heard you do stuff first time really good.” Clarke mumbled disgust, and Crosby offered some ideas how to play. “Instead of that fast, choppy stuff, see, it’s supposed to be a long, smooth slow-floating thing, like a boat.”

Clarke mumbled more discontent, but Crosby cheered him on: “Come on, let’s try it.”

After a couple bars, the next take broke down and Gary Usher, the producer, spoke over the talk-back from the control room, encouraging Clarke to glide over his drums instead of doing a choppy style.

“Come on, fellas,” Usher said. Usher had been in the Beach Boys’ orbit a few years before, so he knew of the producer’s role as cheerleader.

Crosby continued to push Clarke, miming the drum sound he wanted: chicka chicka boom boom chicka chicka boom boom . . . .

Clarke, grumbly and sullen, sat behind the drum kit. This was not the first time David had told him how to play his instrument.

“Try something gentle,” Crosby implored. “Try something pretty. That’s what it’s supposed to be. It’s not beyond you, Michael. You don’t like anything, man, until you get it down right, and then you like it a lot.”

Usher chimed in again, trying to encourage the pissed-off drummer. “Let’s try it a few times, we got plenty of time,” he said.

Crosby still insisted that Clarke didn’t have it, and then the argument turned into a shouting match.

“Try playing right!” Crosby finally yelled at Clarke.

No longer mumbling, Clarke exploded. “What do you mean, ‘Try playing right’? What do you know what the fuck’s right or what’s wrong? You’re not a musician.”

“I know you’re just fucking up when you’re playing,” Crosby said. “Dig it.”

McGuinn tried to intervene, but it was too late. Crosby would not back down. “You’re just fucking up,” Crosby yelled at Clarke. “You’re doing your number.”

Despite the tension, the group attempted a couple more takes, which soon dissolved into chaos.

Crosby threw up his hands. “Can’t you play the drums? Shall I learn you how to play?”

“If you don’t like me,” Michael shot back, “send me away.”

“We love you man,” Crosby said, sincere as a used-car salesman. “We want you to play the drums right!”

“Send me away. I don’t even like the song.”

“What are you in the group for?” Crosby asked. “The money?”

Clarke stormed from the studio.

That night, Crosby called a friend for a recommendation. The next day, session drummer Jim Gordon was hired and he played on the rest of the album.

Crosby was proud of “Triad.” his ode to group sex. The melody was at once lilting and abrupt, jerking through a languid beat. The lyrics described two women, nearly interchangeable in looks to hear Crosby sing it. Then came the key line, repeated at the end of each verse:

But I don’t really see

Why can’t we go on as three

Times were changing. On that he could agree with that asshole Dylan. But his bandmates, McGuinn and Hillman — they didn’t seem to get it. This wasn’t Buddy Holly’s rock and roll anymore. The audience was different now. They didn’t want the boy- and-girl moon-and-June stuff anymore. It was time to push the barriers, to be honest, to reach the audience.

We have just crossed over into The Crosby Zone.

McGuinn and Hillman stood at the door. Crosby blocked the frame. They weren’t looking him in the eye. He didn’t invite them in. They filed past him, too impatient for a sit down. They stood in the living room. Crosby realized he was still holding his guitar.

It was Monterrey, it was the rap about the Warren Commission. And then it was playing with the Springfield — and not even giving them a heads up. I didn’t know it was happening until it was over, McGuinn said. So this is about indignity — his humiliation. What kind of bandleader was he if he couldn’t keep his rhythm guitarist in order?

McGuinn was doing most of the talking. Hillman stood there, arms crossed over his chest, looking at his shoes when Crosby looked his way.

So we think this is for the best, they said. We think we’ll be better off without you.

And then they were gone. The Twin Porsches roared away and David Crosby was alone with his broken heart.