Bombarded by communication we may be, but there is still the possibility for something personal within our over-ripe and festering mass media.

We can watch television — doesn’t matter if it’s traditional network or streaming — and not really have a sense of who’s running the business.

Same thing goes with traditional news organizations, those things we used to call newspapers that now have little to do with paper. We may read The New York Times, but where do we see the publisher’s personality reflected?

Those big media conglomerates that produce our music and entertainment are as bland as soda crackers — and could well aspire to be that imaginative and crunchy.

But consider the magazine. Good and important magazines still exist and carry forward the DNA of their founders or longtime editors.

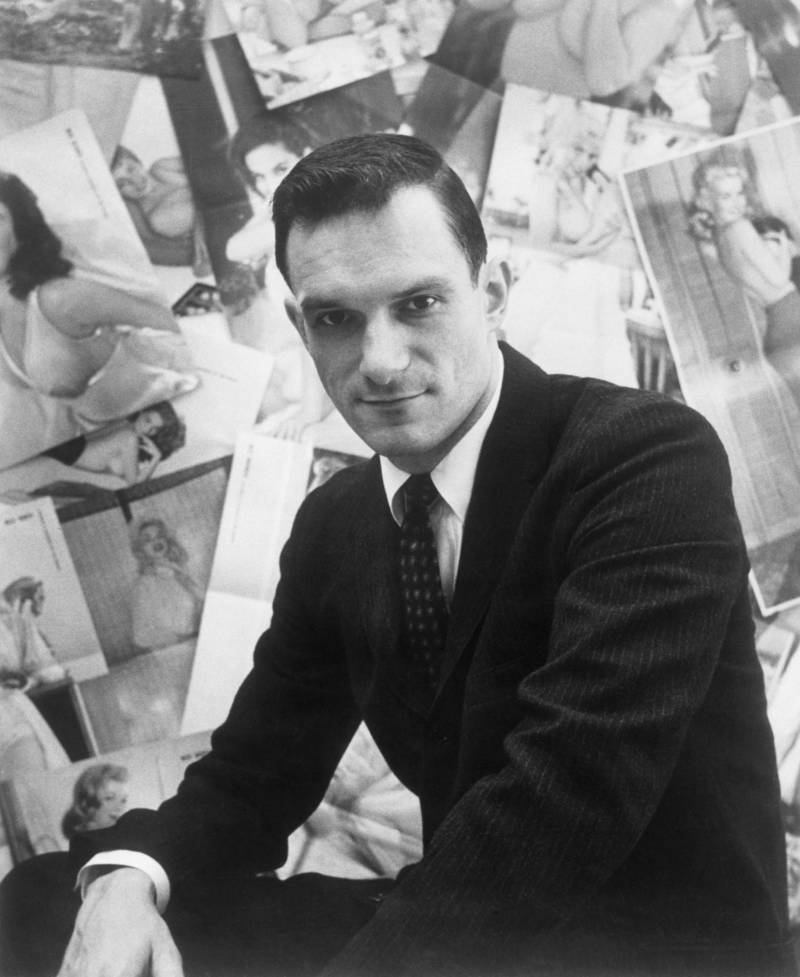

Think of Playboy. Its founder. Hugh Hefner, made sure his magazine reflected his interests and tastes.

When he hopped off to the bunny ranch in the sky, the magazine went into an immediate skid.

Does it still exist? Does it matter? Let me know, will ya?

In the early 1960s, Helen Gurley Brown took Cosmopolitan, a men’s magazine that had published fishing and hunting stories by Ernest Hemingway, and turned it into the bible of the single working woman.

It was a brilliant move because it created an ever-renewing demographic. Brown is getting mani-pedis in the sky, but her work lives on.

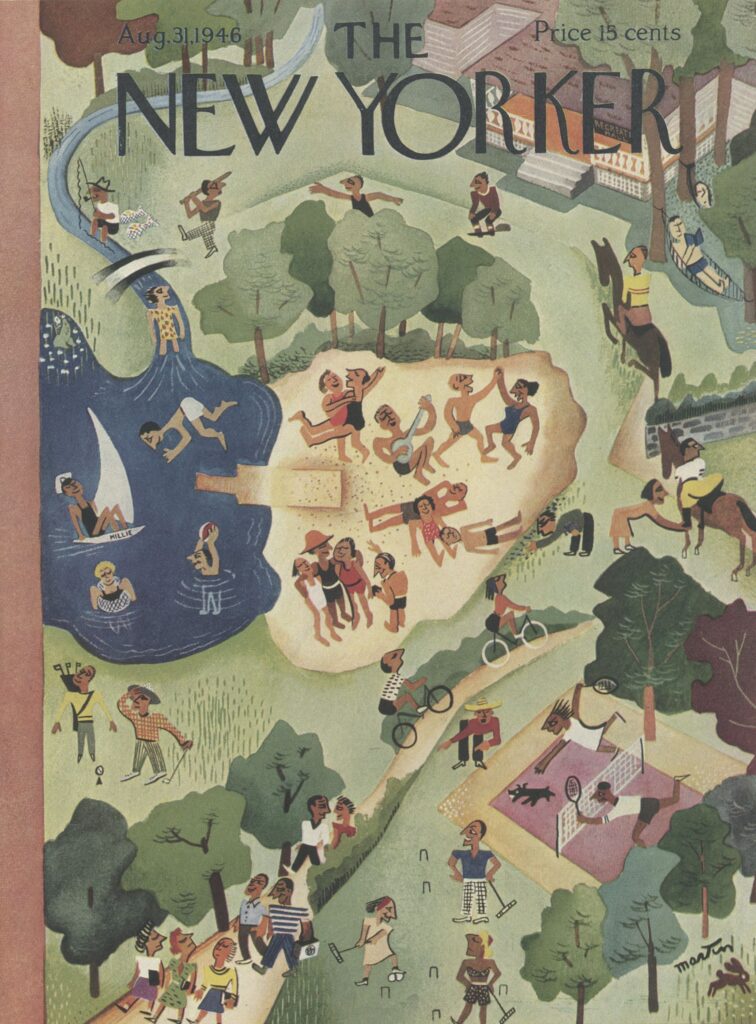

The New Yorker has been blessed with strong editors. Its founder, Harold Ross, liked humor, cartoons and fiction. There was no doubt who ran the place in his lifetime.

But when Ross died, his No. 1 assistant, William Shawn, became editor and changed the magazine as he served for the next 35 years.

Shawn’s interests in long-form nonfiction reinvented the magazine. Few venues of any kind will give storytellers the space that Shawn allowed.

This is a blessing yet also a curse. Some New Yorker writers began writing sentences in the 1980s that have yet to conclude.

Time shuffles on.

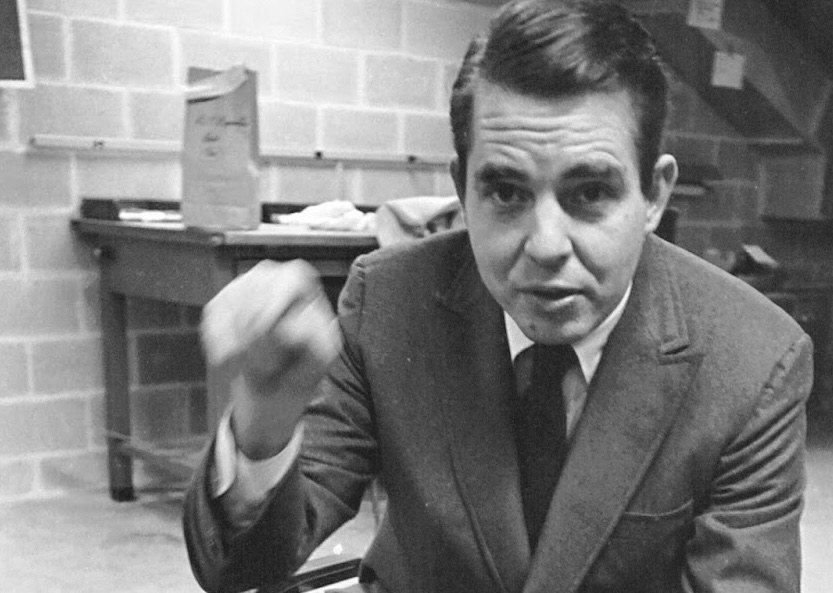

Esquire magazine (under Harold Hayes’s editorship) became the defining voice of the 1960s.

The magazine published so much brilliant stuff in that era that it’s difficult to think of a publication with a better voice for the times.

Its collection of articles from that decade was titled by Hayes: Smiling Through the Apocalypse. (Has there ever been a better title for anything?)

As Hayes was leaving the editor’s chair, along came a rowdy rock’n’roll magazine based in San Francisco that put itself on the cultural map by publishing a full-frontal nude photograph of John Lennon and Yoko Ono. (This exposure of celebrity genitals drew the fans-of-famous-foreskin demographic.)

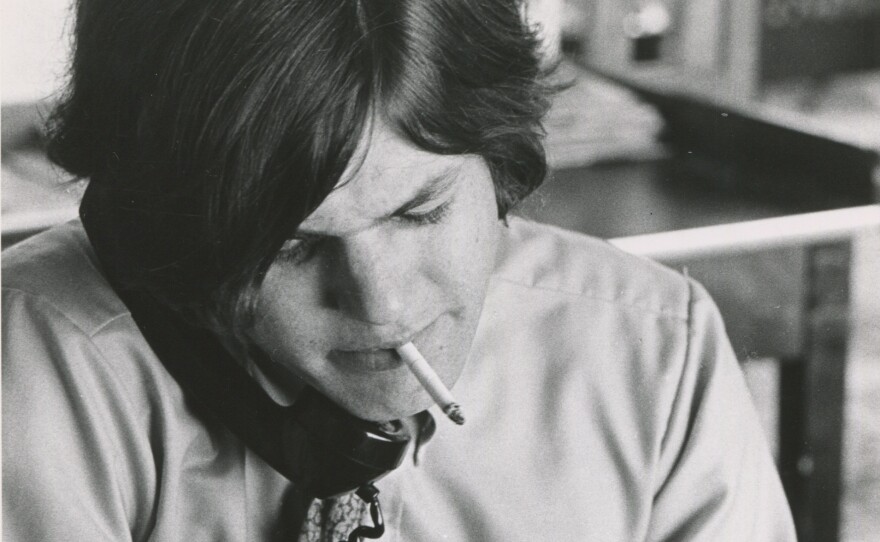

College dropout Jann Wenner founded Rolling Stone in 1967 and for the next quarter-century, under his tight control, the magazine published things he found interesting. Those things became our interests.

Wenner also liked to put his friends on Rolling Stone’s vaunted cover, which was fabled in song.

As Wenner withdrew to the ski slopes and left running the magazine to others, it began losing its way and discovered its problem was the reverse of what happened at Cosmopolitan.

Whereas there will always be single working women to read Cosmo, Rolling Stone was faced with a critical problem: its core readership was tied to a generation that was rapidly aging and dying. In the early years, when Wenner was young, so were his readers. He published the magazine for his peers.

Advertisers looked at Rolling Stone as a clear connection to young, affluent buyers.

But then we got old. The magazine had a core interest in popular music. As the subscribers aged, the magazine sometimes tried to push flavor-of-the-month artists at the Classic Rock audience. It was like the old guy showing up at a college kegger wearing a gold medallion in a desperate stab at youth.

For a while, Rolling Stone was the magazine that defined its times.

I was part of its target demographic from the start. When it would arrive in the post, I used to go into what my then-wife called my “Rolling Stone coma” until I had sucked all of the marrow from all of the worthy articles I found between the covers.

The magazine peaked in the early 1970s, when its roster included David Felton, Grover Lewis, Hunter Thompson, Ben Fong-Torres and Annie Leibovitz, among others.

You’ll notice Leibovitz is the only woman mentioned. The only way a woman could get a job on Rolling Stone‘s editorial staff was to start as a secretary — perhaps another reflection of the founder’s personality. (Leibovitz was the exception. )

Wenner developed so much talent at the magazine, but once the magazine had made it, he sought the big names — Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote and Caroline Kennedy, who acquitted herself in her coverage of Elvis Presley’s funeral. (Her kicker quote was from the Elvis minion who shaved the King’s sideburns one last time before he was planted in the back yard.)

But Rolling Stone’s relevance dried up by the end of the 1970s, around the time it moved from San Francisco to New York.

The magazine that assumed the mantle of most-likely-to-send-me-into-a-reading-coma came along in the 1980s: Vanity Fair.

The original VF had died before the Second World War, and when it was revived . . . who could tell? It was underwhelming.

The revived magazine committed the worst sin in journalism: it was boring.

Fortunately, it was saved by Tina Brown, the British editor brought over to turn it around, two years after its weak re-launch.

For the subsequent three decades and change, few magazines could compete with Vanity Fair.

Brown left the magazine after eight years to breathe life into its sister publication, The New Yorker, which was staggering along after the departure of Shawn.

Brown prepared that venerable publication for the 21st Century by making necessary overdue changes. For one thing, she acknowledged the existence of photography. Until she took over in 1992, the magazine had never published a photo with any of its editorial copy.

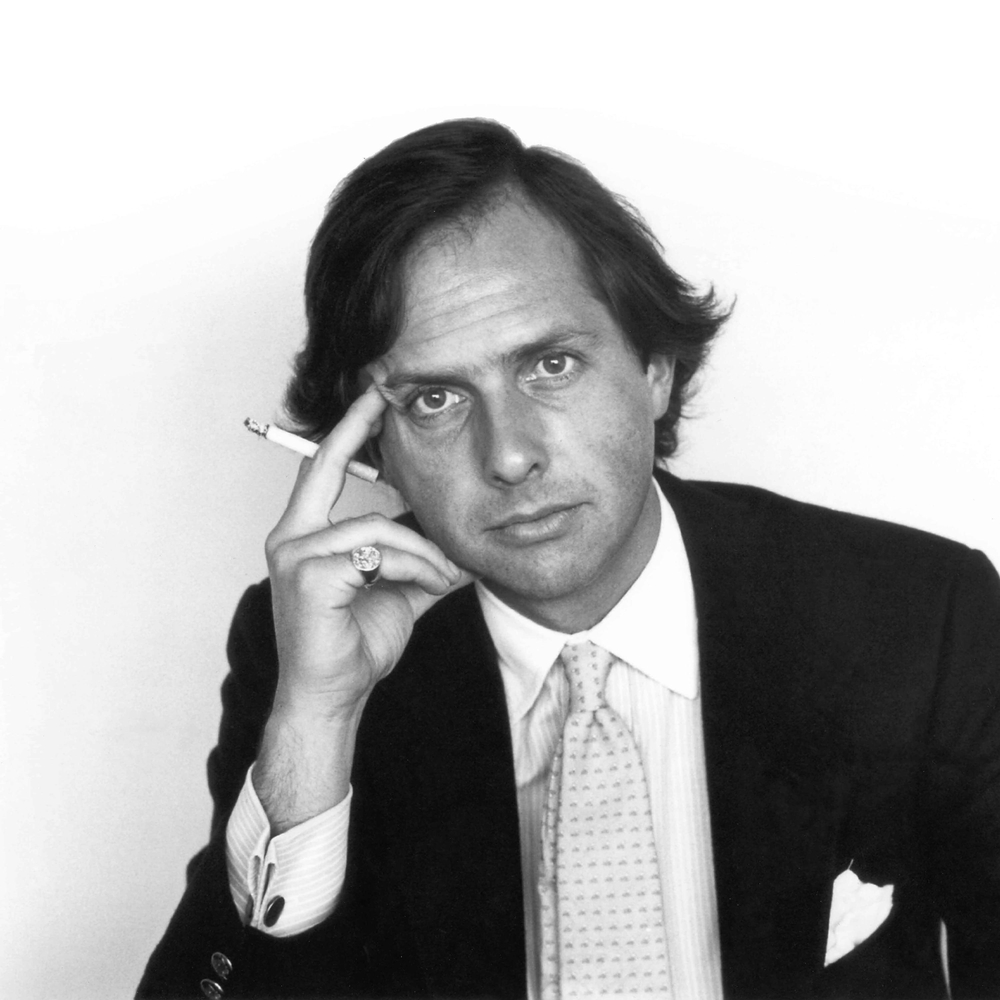

It’s Brown’s successor who deserves the lion’s share of credit for Vanity Fair’s brilliance. He made it into the must-read magazine for a couple of generations.

Graydon Carter recounts his life as a magazine editor in his new memoir When the Going Was Good (Penguin Press, $32).

Journalism is my jam, so naturally his inside baseball stuff is appealing to me.

But I ended up liking the book more for the pleasure of getting to know this guy.

I think this is what I admired the most:

Here is the editor of one of the greatest magazines on the planet. Sure, there are a lot of social obligations and events and dinners and balls. That’s what we expect of the high life, right?

Instead, we find a guy who passes up all of that stuff in favor of a family dinner. He’s home by six every night, and the whole Hee-Haw gang sits down to the table. Everyone talks, everyone learns about what everyone else did all day … you know, wholesome stuff.

Graydon Carter is Ward Cleaver with a better wardrobe. I admire parents who take their job seriously.

He could be hanging out with some boldface names, but prefers family dinners, game nights and fishing in the wilderness with his children.

His tale is a successful story of work-life balance.

Carter was born in Toronto and attended a couple of Canadian universities without graduating. The rigidity of schooling sometimes gets in the way of education, which is something best left to the individual.

He learned on the job, starting with The Canadian Review, which unfortunately went bankrupt.

He moved to New York, worked at Time and Life, co-founded Spy magazine, edited The New York Observer, then took over Vanity Fair in 1992.

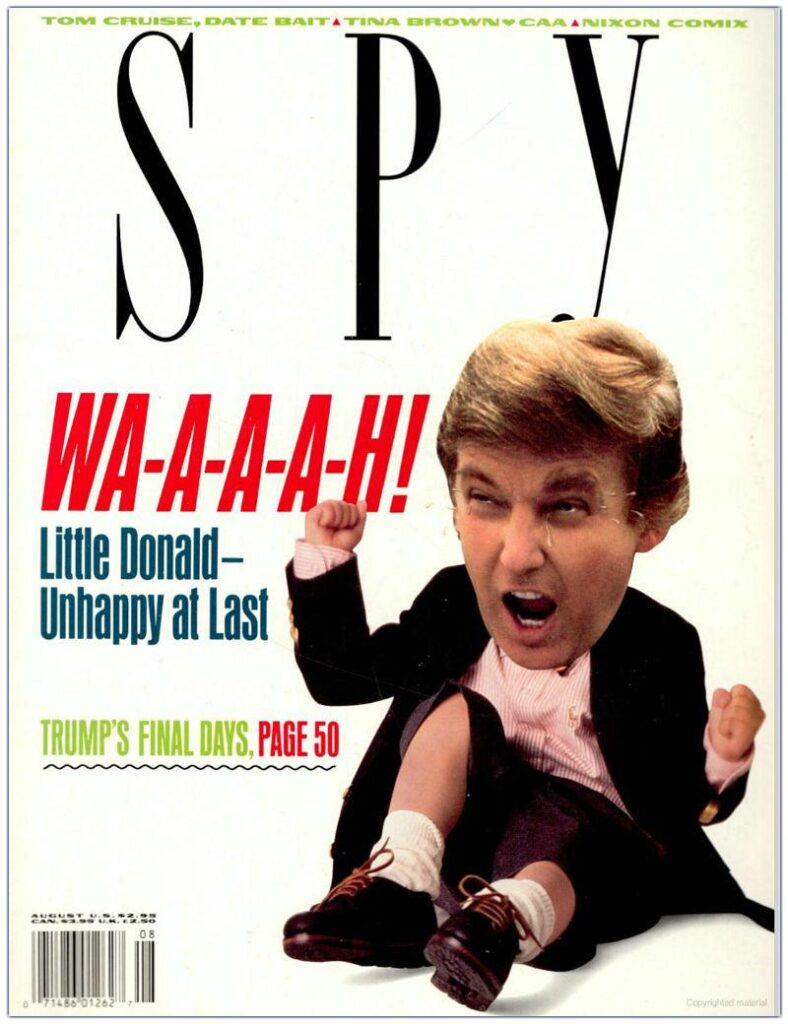

Carter belongs in the history books if for no other reason than this: while at Spy, he coined the term “short-fingered vulgarian” to describe President 45-47. What a rush it must be to have a quip remembered so.

Still, this isn’t a book of journalism gossip. It’s an absorbing, superbly-written account of a well-lived life with a lot of accidents and surprises that led to the pot of gold. It could serve as a guidebook on how to be a good parent.

When Carter edited Vanity Fair it was a work of art, essential to life. Each issue was a king’s feast to be devoured.

Since he left — and started the digital-only Air Mail — Vanity Fair is skidding. It’s no longer a must-read.

Magazines are bound to the personality of the editors. They follow a life cycle, like a human being.

Carter has left the building and that great magazine is having a midlife crisis.

For now, read Carter’s book and remember the great times and the great stories.