Another splendid Record Store Day is in the books, and I am still reeling with the giddy high of the music.

Being a geezer, I confess that most of my selections are rooted in the music of my generation.

For example, I got Joni Mitchell’s Rolling Thunder Revue, culled from her performances on Bob Dylan’s gypsy carnival road show of 1975.

I also got The Warfield by The Grateful Dead, taken from two 1980 shows at San Francisco’s Warfield Theater.

But the real prize came later. My favorite record store sold out of it by the time I got there — and I was there by 8:45 am.

Eventually, I tracked down a copy of it.

It was the reproduction of the original version of one of the greatest and most significant albums of my lifetime, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.

That album was recorded and sent out to stores in early 1963, but was recalled by Columbia Records. This was done in part because of a controversial song, but it worked out well for Dylan: He took the controversial song off the album, along with three others. He replaced them with brand-new compositions: “Girl From the North Country,” “Masters of War,” “Talkin’ World War III Blues” and “Bob Dylan’s Dream.” That last is one of my favorites from his early albums. It still gives me chicken skin.

If I had one of those original Freewheelin’s from 1963, one that had been recalled by the record company … why, I could afford to pick up your tab for dinner. Some copies of the original Freewheelin’ have sold for $35,000.

So, with my life enriched by two Freewheelin’s, I’ve jumped down the rabbit hole of Bob Dylan research and I’ve noticed an error that has been fruitful and multiplied.

I must call bullshit.

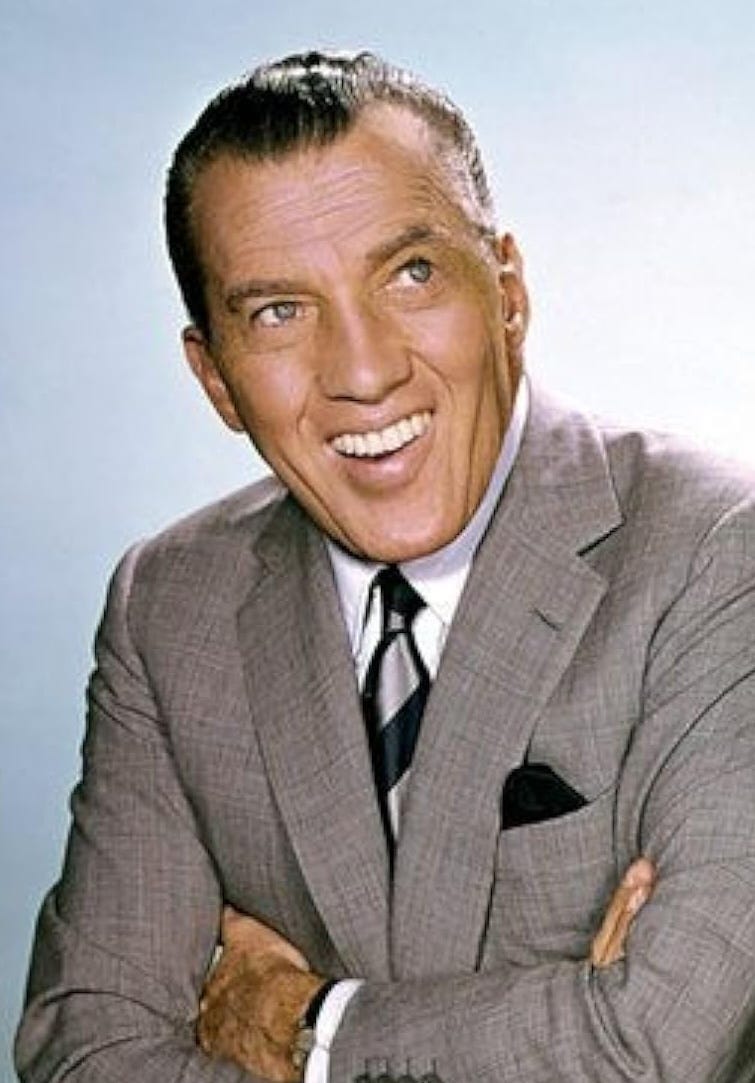

Even Goldmine, that wonderful magazine about music and records, makes the occasional mistake. In its piece on the Freewheelin’ / Record Store Day hoopla, the magazine says “ ‘Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,’ [is] the song that prompted Dylan to walk off The Ed Sullivan Show when Ed wouldn’t let him play it.”

In another story, actor Steve Buscemi makes a comment aimed at the deceased Ed Sullivan after reciting the lyrics to “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues” at a Dylan tribute concert. “With all due respect, you blew it, man!”

I admire Buscemi as an actor, firefighter and humanitarian. But I hope he will understand when I say, “You’re out of your element, Donny.”

Sullivan supported Dylan and wanted him to do the John Birch song. A representative from CBS’ standards and practices office — in short, a censor — said Dylan could not do it. The censor overruled.

Every trusted source in my Dylan library affirms this story.

Ed was a good guy. OK, he was so wooden that redwoods withered in his wake. Speaking did not come naturally to him and watching him try to engage in post-performance smalltalk with his guests was excruciating. He might’ve invented cringe television.

But this man with no discernible talent hosted for a couple of decades the epitome of a television variety show.

And despite the protests of CBS’s affiliate stations in the Deep South, he booked whatever entertainer he wanted.

In the early and mid-Sixties, some stations down south put a sign onscreen when a black entertainer appeared: “Due to circumstances beyond our control, we have lost our programming.”

Sometimes, the stations put up test patterns of stand-by signs. When the black entertainer finished his or her set, the feed from New York would be magically restored.

Ed Sullivan didn’t give a shit. If he wanted James Brown on his show (his “really big show”), then he’d book him. (Ed was especially fond of Brown.)

Here are some of the artists Ed booked, southern affiliates be damned:

Louis Armstrong, Harry Belafonte, James Brown, Cab Calloway, Diahann Carroll, Ray Charles, Chubby Checker, Nat “King” Cole, Sammy Davis Jr, Bo Diddley, Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, The Jackson Five, Mahalia Jackson Gladys Knight, Sidney Poitier, Billy Preston, Smokey Robinson, Nina Simone, The Supremes, Tina Turner, Dionne Warwick, Ethel Waters, Flip Wilson and Stevie Wonder.

Eventually the walls came tumbling down. Down south, viewers began to hunger to see these great entertainers and the affiliates eventually caved.

Don’t believe me? Navigate your television to a Netflix documentary called Sunday Best, which tells the whole story.

So give Ed his due. In your memory, you think of him as comical, talentless man. But the evidence points to the mark he made on our culture. Among his many accomplishments, he stood up for Bob Dylan. He was overruled by the censor, but he was a man of principle. He may have had the personality of a tennis shoe, but he stood for something.