Chicken Skin Music was the title of a Ry Cooder album of long ago. The title referred to music that gave you chills.

Since we waste time on social media with lists, I decided to list the songs that unfailingly give me this feeling.

Goose bumps. Hair on the back of the neck. That stuff.

I’ll try to be specific and point out the parts of songs that affect me so.

This is just today’s list. Another day might be radically different. For instance, Celtic music is absent here, yet I listen to it a lot at home and have that strange and magical chicken skin feeling.

Great collection of songs here. You can thank me later for giving you this wonderful afternoon of listening.

Let’s start with Ryland Peter Cooder.

“Rally ‘Round the Flag” by Ry Cooder. He sounds like the last survivor of Chickamauga. He can barely mutter the battle cry of freedom, but he’s determined to try, This might get us off to a slow start with our musical program, but so what? I believe that’s Van Dyke Parks on piano. Great slide playing, of course. Ry Cooder, duh.

“My Back Pages” by the Byrds. The whole thing, but especially McGuinn’s evocative solo. We could also add “Chestnut Mare.” To me, the solo carries the emotional weight of the brilliant lyrics. This has become my motto — I was so much older then; I am younger than that now.

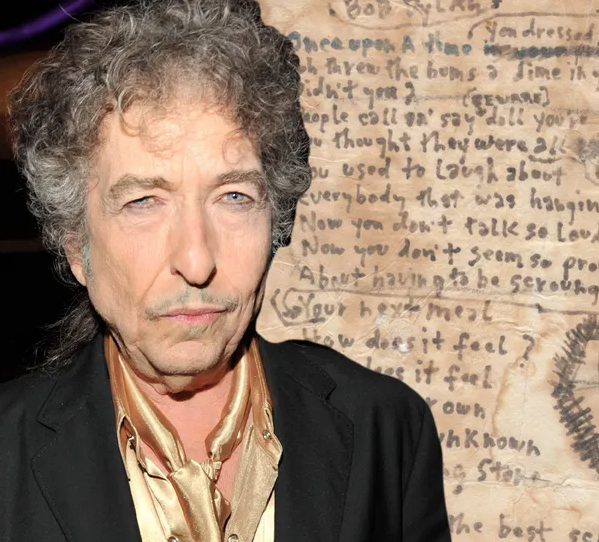

“Series of Dreams” by Bob Dylan . Especially his buildup to the fade and the fade. There’s something swirling and mythic and wonderful about this song.

“The Dark End of the Street” by Aretha Franklin. There are so many great versions of this song, from James Carr‘s original to the version by the songwriter, Dan Penn. But the bridge of Franklin’s version takes us to Jupiter. It’s truly, deeply otherworldly. And that desperation: “They’re gonna find us, they’re gonna find us.”

“Mother Country” by John Stewart. Especially the second verse about the blind man in the sulky. I don’t like narration in songs, but John Stewart pulls it off. From the opening strum, this song has me.

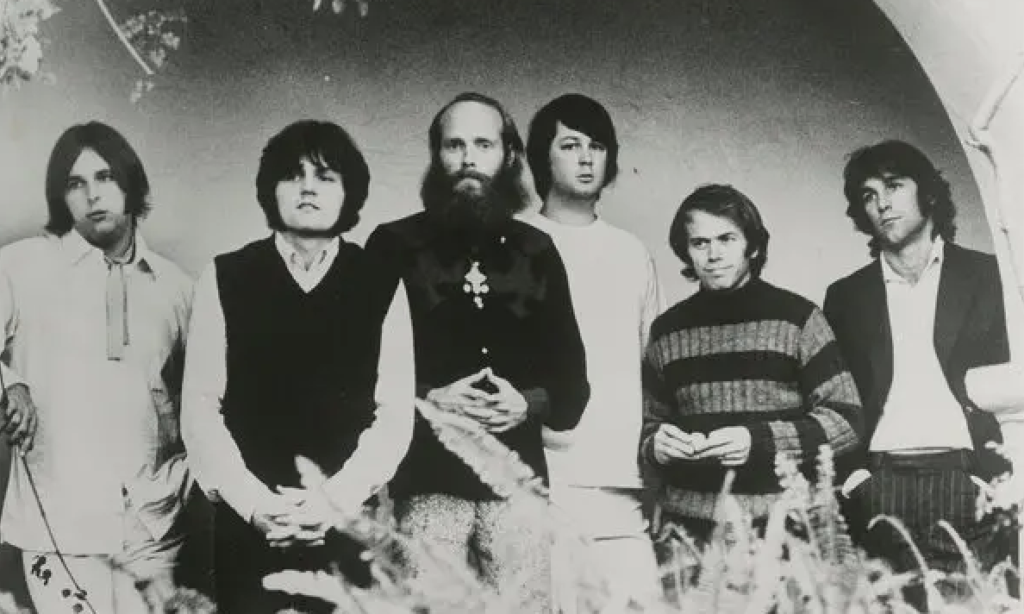

“This Whole World” by the Beach Boys. Brian Wilson’s moment at the end, when the instruments drop out and it’s just him. Or maybe that’s Carl Wilson. They give us this whole world … and they bring it in under two minutes. This is beauty and craftsmanship.

“Not Fade Away” by the Rolling Stones. The opening chords. I fucking love Buddy Holly, but dude, the Stones beat you at your own game on this one.

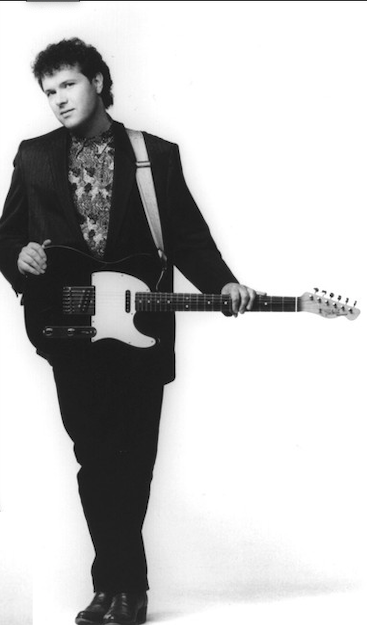

“Gulf Coast Highway” by Nanci Griffith. She kept re-recording this, but she got it right in the 1989 recording with Mac MacAnally. When she gets to the final verse, I nearly go into a coma. If only she ‘d spelled her first name Nancy, she would have been perfection.

“Candy’s Room” by Bruce Springsteen. After the whispered introduction, Max Weinberg’s drums explode into the song and create one of those Great Moments in Rock’n’Roll History.

“Sweet Old World” by Emmylou Harris. Just about everything on the “Wrecking Ball” album gives me chills. It’s that Daniel Lanois fellow, her producer. He knows how to push those buttons. For more Emmylou chicken skin, listen to her Christmas album as Neil Young flies in from Mars to warble ‘hallelujah’ in the background of “Light of the Stable.”

“Four Strong Winds” by Ian and Sylvia. The whole damn thing. A nearly perfect recording. Ian Tyson gets the testosterone boiling. This is a beautiful blend of male and female voices. Sylvia Fricker sings so beautifully on “Someday Soon.”

“Add Some Music to Your Day” by the Beach Boys. A pleasant enough song until midpoint, when Brian (or is it Carl?) sings, “Music, when you’re alone, is like a companion for your lonely soul.” Then he soars. Poultry time, my friends. Pawk, pawk.

“Bugler” by The Byrds. Sung by Clarence White. A boy tells us how his dog, his best friend, died. This reminds me so much of my childhood in Texas … and that old movie, Biscuit Eater. (Don’t get me started on Old Yeller.) When one of our family dogs died, we were not allowed to utter the dead dog’s name again. Dry your eyes and stand up straight — Bugler’s got a place at the pearly gates.

“That Lovin’-You Feelin’ Again” by Emmylou Harris & Roy Orbison. Lord, I’m a mushpot. But I can’t deny that I love this song. What beautiful voices.

“Like a Rolling Stone” by Bob Dylan. Yes. Every time I hear it, I’m slayed. I’ve never been able to hear this without turning it up. I especially like it as the song roars toward the conclusion and Dylan makes that sound, as if he can’t himself believe what he’s in the middle of doing. Fucking awesome. Every time I hear it.

“Making Love (at the Dark End of the Street)” by Clarence Carter. He used only one verse from the original song, and spends the first part of the song preaching about cattle copulating. Never have I heard the ridiculous and sublime so well married in a song. After talking about mosquitos fucking, he manages to achieve some kind of majesty at the end of the song. Chills. And marvel: how did he do that?

“Hello in There” by John Prine. Thinking about my late grandparents. Prine’s whole body of work is chicken skin music. Sometimes, his songs are so good that I can’t listen to them. I’m afraid I’d collapse. On The Tree of Forgiveness (2018), his last album, there’s a song called “Summer’s End.” It destroys me. From beginning to end, John Prine had it.

“2000 Miles” by the Pretenders. The way Chrissie Hyde’s voice rises as she sings “it must be Christmastime.” I have a firm tactile memory of this song — driving cross-country through a blizzard to see my children. I always associate this and Dylan’s Infidels and Emmylou’s Wrecking Ball as cold-weather albums.

“Me and the Wildwood Rose” by Carlene Carter. The best and most autobiographical song on an album dealing with her considerable family legacy. The last verse moves one to tears. Great storytelling. If you loved a grandparent, you’ll understand.

“The Lakes of Ponchatrain” by Trapezoid. Feel free to assassinate me while this song is playing. It’s so beautiful, I won’t mind. Really. The dulcimer solo carries home this song of doomed and impossible love.

“Mama Tried” by the Everly Brothers. On the great Roots album, this follows a snippet from an Everly Family radio broadcast when Don and Phil were in single digits. That moment, when the broadcast ends and the opening of this Merle Haggard cover begins, is one of many high points on that great album. Also: a slow remake of their early song, “I Wonder if I Care as Much.” Sorry, Merle, this is the odd moment when a cover version beats your original — but just by a badger hair.

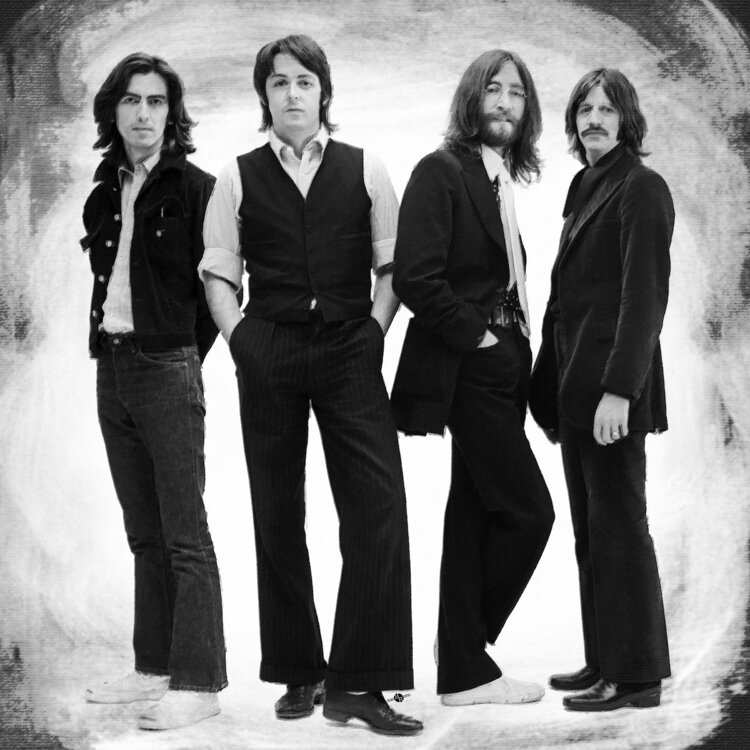

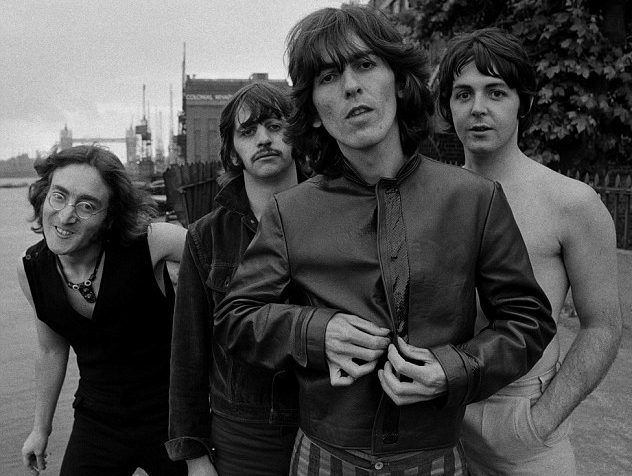

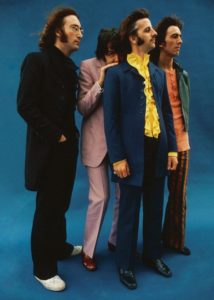

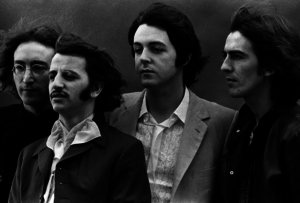

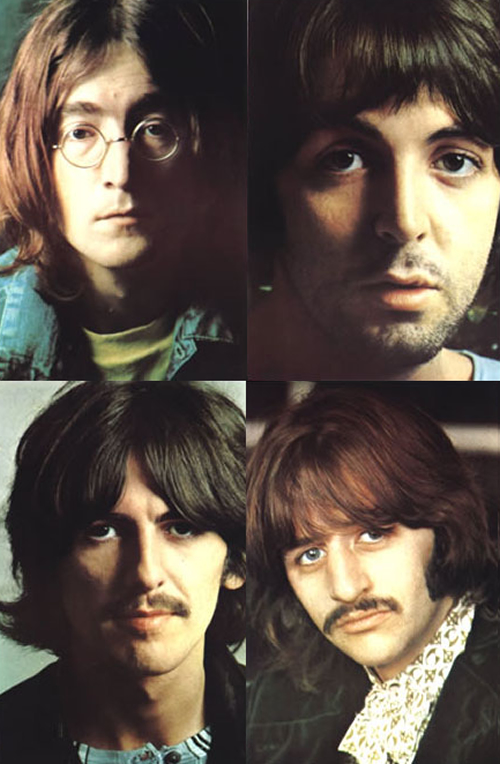

“Hey Jude” by the Beatles. My favorite Beatle song, especially for the fade – and for the time and place where that song came in my / our history. This song is so connected to that tumultuous, overwhelming year, 1968.

Pet Sounds by The Beach Boys. The whole thing. A cop-out, I know, but when I hear “Wouldn’t it be Nice” — especially the fade –- “Sloop John B,” “God Only Knows” and the rest of it, I’m both exhilarated by the beauty of the music and saddened that the world is without the angelic voice of Carl Wilson. Carl could even take a weak song – Mike Love’s “Brian is Back” comes to mind – and turn it into a thing of beauty. When I hear them fading away at the end of “Wouldn’t it Be Nice,” they truly are forever young.

“Spanish is the Loving Tongue” by Michael Martin Murphey. The singing and playing is beautiful and the song even manages to overcome one verse that is spoken, not sung. I’m a mushpot, so this one always gets to me. You know who you are.

“Born to Run” by Bruce Springsteen. Sorry to be so obvious. This is the best Phil Spector record that Spector never made. Phil would have crammed this whole world into a shorter record. Too bad how it ended with Phil. I’d like to see his remix of this. I bet he’d bring it in under three minutes. It would be a tight, claustrophobic record.

“Blind Willie McTell” by Bob Dylan. Hypnotic. Masterful. This song never fails to get to me. Wonderful use of language and image. And to think – it was an outtake. “Lord, Protect My Child” is another beautiful Infidels outtake.

“Highwater (for Charley Patton)” by Bob Dylan. One last Bob song. This is of a piece with “Series of Dreams” and “Blind Willie McTell.” This is Dylan’s whole history of the doom and dread of the 20th Century. I’m utterly drained after every listen.

What’s Going On by Marvin Gaye. The whole thing. When I got the original LP, I thought, “This album is so great that if there isn’t a Side 2, I’d still be happy with it.” That suite on Side 1 is so beautiful, especially when Gaye preaches and begs us to save the babies! save the babies!

I can’t type anymore.

Chills, dude, chills.

Things had changed by 1968 and I was ready when the White Album hit. Back then, young sprogs, our parents didn’t just buy us stuff and we didn’t get handed an allowance. The folks expected us to work for money. And since the White Album was a double-album, I’d need to work extra hard.

Things had changed by 1968 and I was ready when the White Album hit. Back then, young sprogs, our parents didn’t just buy us stuff and we didn’t get handed an allowance. The folks expected us to work for money. And since the White Album was a double-album, I’d need to work extra hard. Without help, I spent a day working in the back yard. When I called my father outside at dusk, he marveled at my work, then handed me a $10 bill. I rode my bike to the Woolworth’s — luckily, owing to the early sunset of November — only a half mile away. The album was mine.

Without help, I spent a day working in the back yard. When I called my father outside at dusk, he marveled at my work, then handed me a $10 bill. I rode my bike to the Woolworth’s — luckily, owing to the early sunset of November — only a half mile away. The album was mine.

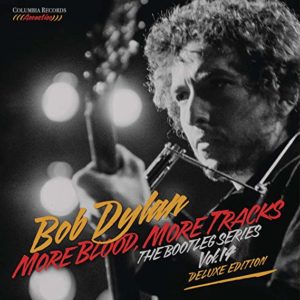

Dylan had second thoughts. He played the acetate of the album for his brother while visiting Minnesota in December. David Zimmerman told big brother he could do better. Or something. But he hired a studio, found some local musicians, and got Big Brother Bob to re-record half of the album.

Dylan had second thoughts. He played the acetate of the album for his brother while visiting Minnesota in December. David Zimmerman told big brother he could do better. Or something. But he hired a studio, found some local musicians, and got Big Brother Bob to re-record half of the album.