I’ve never been to a film festival, but I’ve read about 10-minute standing ovations at the end of a Cannes screening.

The closest I came to anything like that was the night that Annie Hall opened in my hometown. There was an ass in every seat, no loudmouth back-talkers, and everyone laughed in the right places. Then, of course, the Standing O.

It was one of the highlights of my movie-watching career.

Not every Woody Allen film has gotten that kind of reception.

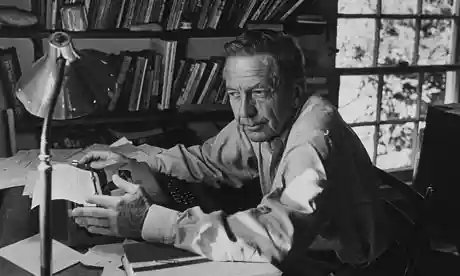

His humor and storytelling were briefly in planetary alignment with mass taste for a few years, but then he spiraled off to his own galaxy, making his quiet, esoteric films — some of which occasionally found a decent-sized audience (Hannah and Her Sisters, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Midnight in Paris, to name a few).

I’ve enjoyed more of his movies than I’ve disliked. That’s wrong. I don’t think I’ve disliked any of them, but now and then I find one a wee bit boring or self-indulgent.

I’ve always found Allen’s prose to be more consistent.

He published three collections of his short stories and comic pieces in rapid succession — Getting Even (1971), Without Feathers (1975) and Side Effects (1980). He began publishing prose in the New Yorker in 1966 and kept up a pretty vigorous schedule of contributions.

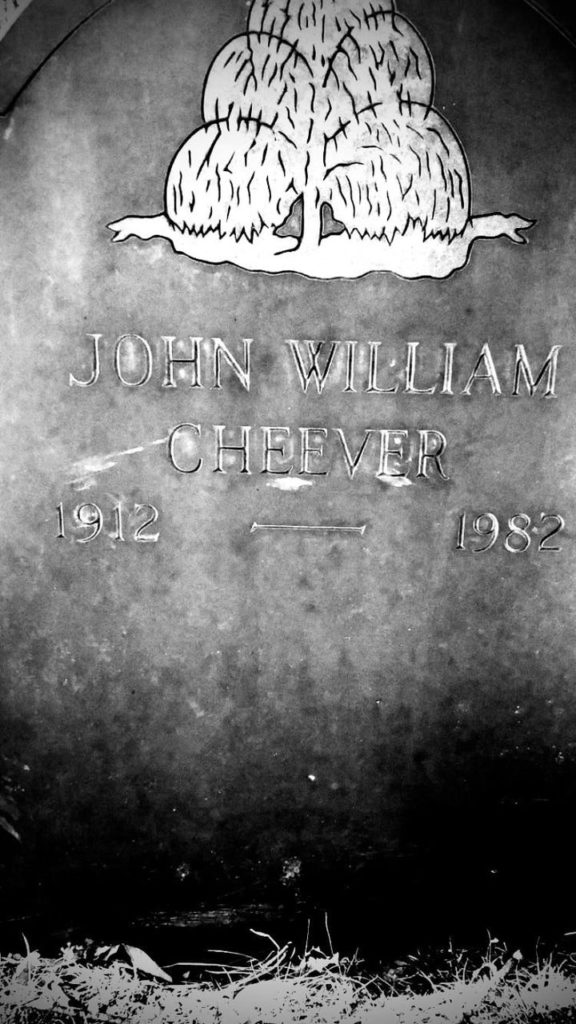

Some of these stories were the kind that made me laugh out loud. Some were honored with recognition that had before been lavished on Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty and John Cheever. (Allen’s “The Kugelmass Episode” won the coveted O. Henry Award in 1978.)

He maintained a film-a-year schedule and still produced short stories — until his prose work slowed to a trickle, then stopped, in the 2010s.

Twenty-seven years after Side Effects, Allen published a collection called Mere Anarchy, but his prose output has ramped up in the last five years. First came Apropos of Nothing, his hilarious and touching autobiography, a collection called Zero Gravity and now, at 89, his first novel, What’s With Baum? (Post Hill Press, $28).

Certain doors are no longer open to Allen. He signed a deal with Amazon Studios but has still struggled to release his films. His previous big-time publishers (Random House, Little Brown) no longer publish his work, so he has aligned with Arcade and Post Hill Press, two smaller pubishing companies.

Too bad that his books and films are not getting the distribution he used to get. His work has not lost a step.

Reading What’s With Baum? Is like watching one of his films. It’s structured that way and has a plot and a narrative approach that lends itself to screen treatment.

Baum is a once-promising writer experiencing several varieties of writer’s block. His third marriage has come with a son who loathes Baum. The boy is poised for success, including magazine and television profiles, and with his new book being hailed as a work of genius.

But Baum discovers a dirty little secret about the boy and the book and becomes, at least among his family and social set, the avatar of ethics.

It is a masterfully written book. Few storytellers have Woody Allen’s gifts. I hope he is able to continue sharing his stories.