I used to go into a coma when Rolling Stone arrived in the mail. I started subscribing when the magazine was two years old and read it religiously. I wouldn’t look up from those newsprint pages until I’d read pretty near everything.

I think the magazine peaked in the early and mid-1970s. I remember a piece about a guy who was obsessed with meeting his hero, Gene Autry, former singing cowboy of the movies. And there was a great portrait of Sen. Sam Ervin, the country lawyer who led the Senate’s Watergate investigation. Then there was a marvelous book-length tick-tock about filming The Last Picture Show by the great Grover Lewis.

Wonderful storytelling — and it ranged over the culture. It wasn’t all about rock’n’roll music.

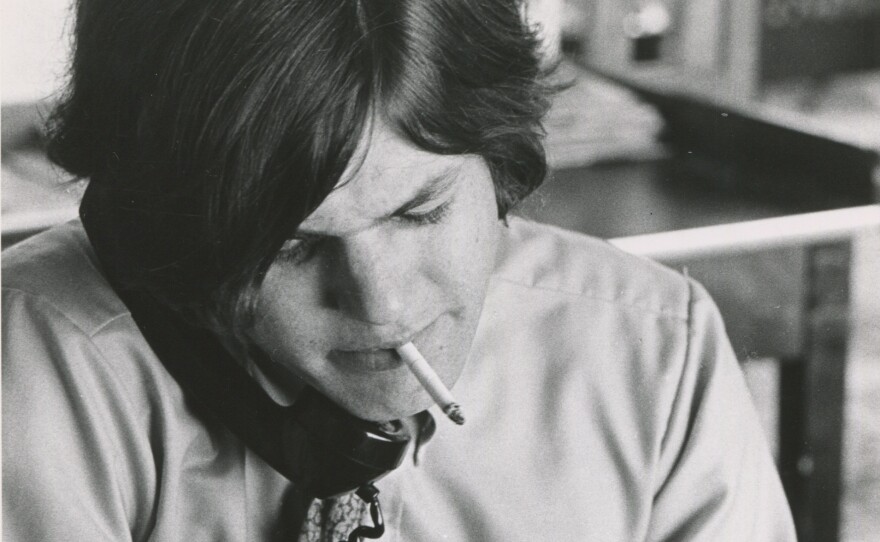

And then — suddenly — a new byline: Cameron Crowe. It didn’t take long for word to get out that he was a real kid, 15 years old — our age.

He thus became our role model. I started working full time for my local daily when I was 14 and stayed on the job until the newspaper folded a few years later.

As a young peach-fuzzed reporter, it was a struggle to be taken seriously. No matter what I did, I still looked my age. But I asked good questions (I think) and my sources soon began talking to me like I was an adult.

I imagined what it was like for Crowe. He was talking to the Allman Brothers and Joni Mitchell and the Eagles. I wanted to know his secret. They obviously took him seriously — the stories he wrote were brilliant.

I was following rock stars on a much smaller scale. These backstage expeditions were in the company of my pal, Neil Sharrow, aka Birdman (sharrow = sparrow). He was much more savvy when it came ti talking to roadies and stage security.

We got into the dressing room for Yes and had a great chat with keyboard wizard Rick Wakeman. As we left, he said, “Best of British luck to you,” and that became a benediction I often use.

We also got to meet Chicago. I interviewed them later, extensively, for a national magazine, but that chat was set up by publicists. I had more fun hanging out with them in the parking lot when they were just breaking through to the mass audience.

And of course, I followed The Beach Boys around and interviewed them several times, and one afternoon, we were sharing backstage airspace with the Boys, the Eagles and Kansas.

Now, this was nothing like what Crowe was doing, but this was a side gig for me. I also had to be a college student and cover the environmental commission’s long running efforts to bring noise-abatement to the city. I spent a lot of time at city hall — more time than I spent on campus. I didn’t hang with Neil Young; I hung with the mayor, whose name was Hooker.

Of course I followed his work — Fast Times at Ridgemont High (first a book, then a film) , then his splendid films, Singles, Say Anything, Jerry Maguire and, eventually, Almost Famous.

That was a nearly perfect movie — so well-written, so well-acted, and a story with the aroma of truth. That’s what it felt like to be a kid reporter, trying to stalk a rock star. It dislodged so many memories of my much-lower-scale life, and hulking brutes at the stage door coming between those rock stars and me.

I think I’ll put this on my tombstone: You’re not on the list.

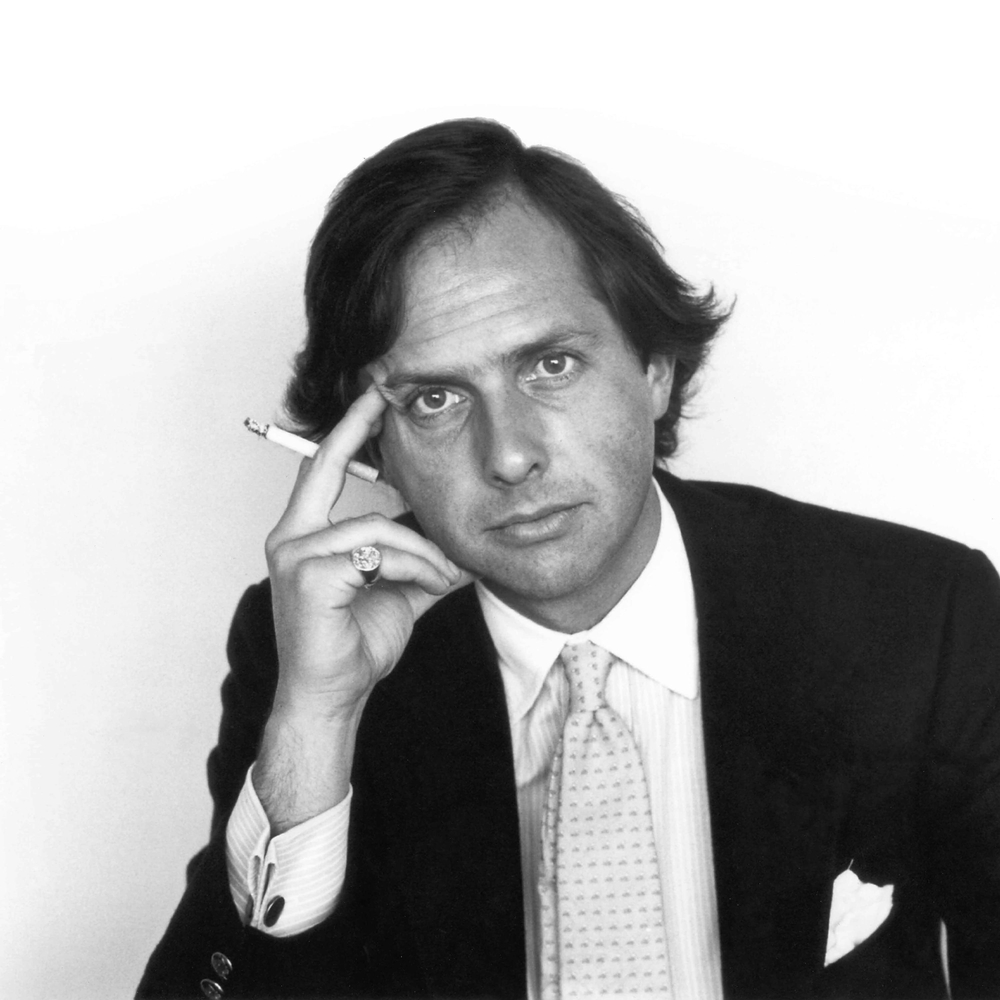

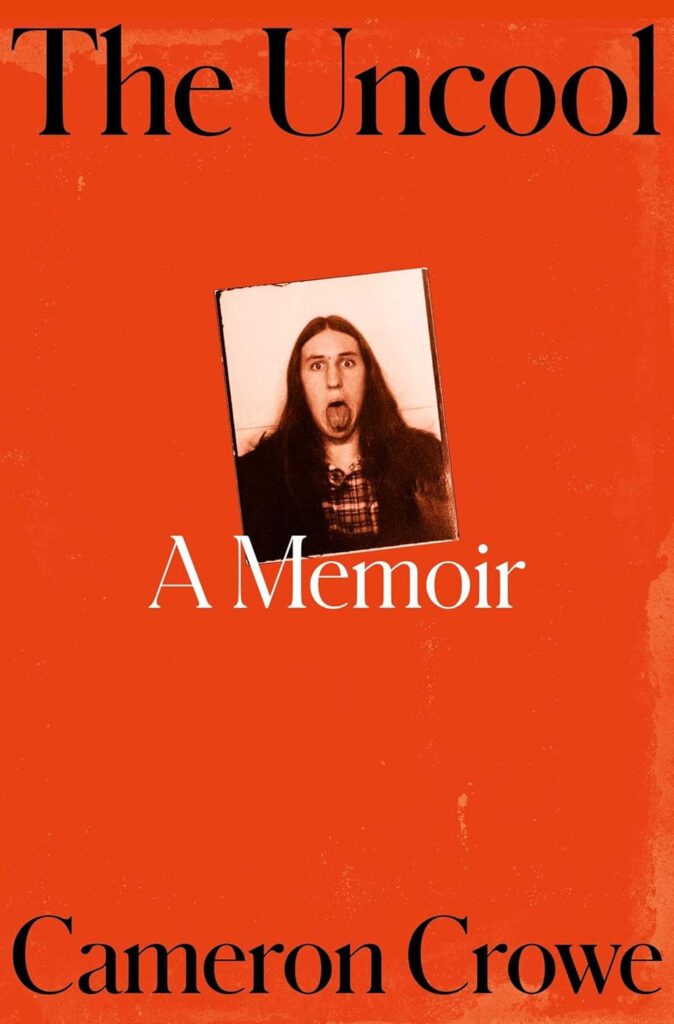

All of these memories began to erupt when I got Crowe’s excellent new book, The Uncool (Avid Reader Press, $35). As he pages through his life, we find the roots of his Almost Famous stories, and we meet the real people behind the characters.

First among his cast of characters is his mother, Alice Crowe. I was also blessed with caring and supportive parents, so when he writes about Alice, I get a little misty. When he filmed Almost Famous, he wanted to keep the actors apart from their counterparts. But Alice ignored her son’s directive and became great friends with the sterling Frances McDormand, who played her.

Crowe is a master storyteller, no matter the medium. The book is peopled with Joni Mitchell, Tom Petty, Gregg Allman, the members of Led Zeppelin and a wonderful cast of supporting players at Rolling Stone. And of course, he writes about his mentor, Lester Bangs, who explained why they were both doomed to be the Uncool.

I inhaled the book and tried to slow down my reading as I got near the end. I wanted to make it last longer. After all, I’ve been reading Crowe and enjoying his work for 50 years.

He’s also done a book on his talks with master filmmaker Billy Wilder. For his next book, I hope he collects this great pieces he wrote for Rolling Stone back in the 1970s, with headnotes that describe his adventures in getting the story.

This is a tremendously entertaining book. I can’t be blamed for wanting more..