My father died when I was young, and there are a few million things I wish I could talk about with him. He was 53 and I was 20. I’ve significantly outlived him.

I inherited most of his books — and it’s daunting. He had everything. Go into my living room, where I keep this prized library, and you’ll find an impressive collection of world literature. Run your fingers over the spines: Thuycides, Plato, Aristotle, through all of Jane Austen and Henry James, and that fun couple, Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

I have a beautiful edition of Leaves of Grass, printed (appropriately) with a grass leaf cover. I have his copy of The Bible as Living Literature.

He loved Vladimir Nabokov, and could recite parts of Finnegans Wake from memory. He was a huge fan of James Joyce and so the portrait of Joyce next to the living-room bookshelves — which I purchased from a Dublin street artist — is there in tribute to him. I’ve appreciated Joyce’s short stories but never made it through Ulysses or Finnegans Wake.

I have such strong memories of my father performing passages basso profundo.

But his tastes were so catholic. Note lower case.

My father was one of those guys with a book in every room — living room, family room, bedroom, bathroom. Different books for different moods.

I share one of his addictions, though mine did not appear until many years after his death. We both love(d) detective fiction.

I remember when we were stationed in England in the 1950s. Dad had a lot of paperback mysteries strewn around the house. My brother got custody of those books when Dad died, so I’ve been playing catch-up.

The recent HBO series devoted to the Perry Mason origin story got me reading the Erle Stanley Gardner omnibus my son Jack bought for me last year at a garage sale. Mom and Dad used to devour those books.

I bought a few Raymond Chandler collections from eBay. Dad, in particular, loved Chandler.

And there was a less-well-known writer, named John Dickson Carr. I remember so clearly my father reading his book, The Problem of the Wire Cage. I await the arrival of a battered 60-year-old paperback from eBay.

I wish I could talk over these books with my Dad. I was so unformed when he died. In the last year of his life, he bought me two books that meant so much to me — The Boys on the Bus by Timothy Crouse and In Cold Blood by Truman Capote. I was the only member of the family who showed no interest in following him into a medical career, so he wanted to support me in the work I chose.

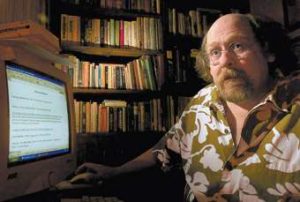

Somewhere along the way, I became a fan of mystery novels. Maybe it started with Carl Hiaasen’s books, back in the 1980s. I’m not sure those are traditional mysteries — they’re more like farces with undertones of ecological skullduggery.

His latest book, Squeeze Me, spoofs the crimes against humanity at the Palm Beach White House, where the president is known only by his secret service code name: Mastodon.

Hiassen’s novels have only a couple of continuing characters. Alternating novels feature Skink, the renegade former governor of Florida. War hero and patriot Clinton Tyree returned from Vietnam filled with idealism and entered public life. He was elected governor, but then became frustrated by the rampant corruption in the state, and so disappeared.

But he didn’t exactly disappear. Tyree went underground as an eco-terrorist, subsisting on roadkill.

Thankfully, Skink appears in Squeeze Me. (He has also appeared in one of Hiaasen’s entries in his best-selling series of young-adult novels. Hoot is the best-known of his YA books.)

Squeeze Me got me laughing during this pandemic, and I wrote about that book a few posts back. Find it here.

But my old man would have really loved books by two writers whose work is like crack to me: Michael Connelly and Tom Corcoran.

Both are known for their long-running series of novels with continuing protagonists. Connelly and Corcoran are so expert at their craft that it does not matter in what order you read the books. You can read the latest Connelly novel about Harry Bosch and not feel left out.

Bosch is the character to whom Connelly most often returns. He was introduced 30 years ago as a Vietnam veteran, born to a prostitute and a (then) unknown father. His mother is murdered, Bosch grows up in foster homes, serves as a tunnel rat in Vietnam before becoming a cop. With each case, he avenges his mother’s murder. “Everybody counts or nobody counts.”

Along the way, Connelly has introduced other continuing characters, including FBI profilers Rachel Walling and Terry McCaleb. He had to kill off McCaleb several years back, because Clint Eastwood bought the rights to a novel featuring McCaleb. The character was around 40, but when he was played by the Great Squinter in Blood Work, Connelly realized he had to dispose of his creation. In a meta moment, Connelly addressed the issue of Eastwood’s major plot twist that perverted the relationships in the Blood Work novel. This showed in conversation, when McCaleb notes — not long before his demise — how it sucked to be played by a geezer in the movies.

Along the way, Connelly created another character. Since he showed a great affinity with police stories, he decided to master the courtroom thriller. Thus was Mickey Haller born. Turns out he’s the half brother of Harry Bosch — we finally find out the identity of the father — and works out of the backseat of his car. Connelly inaugurated a series of Lincoln Lawyer novels, then two years ago, introduced a young detective who lives in a lean-to on the beach, Renee Ballard.

Another continuing character, Jack McEvoy, harkens from Connelly’s days as a newspaper reporter. He appeared in The Poet, The Scarecrow (one of Connelly’s very best) and Fair Warning. Once a mad-dog journalist, these days Jack works for a non-profit reporting collective. Connelly keeps up with the times. His characters often show up in each other’s novels. Bosch might appear in a McEvoy book and Bosch makes frequent walk-ons in the Mickey Haller stories.

(FYI, Bosch is the excellent Prime Video series starring the perfectly cast Titus Welliver as the detective. If you have not seen it, six seasons await your binge. The seventh season is in production.)

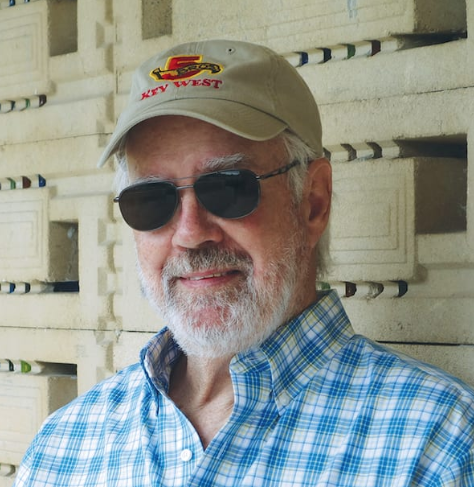

A few years back, the jacket of a Tom Corcoran novel bore a quote from Connelly that said Corcoran’s book Air Dance Iguana was “the reading highlight of the year.”

That is high praise.

Corcoran’s protagonist isn’t a police detective. Alex Rutledge is a Key West photographer well connected to cops and reporters and gets roped into solving mysteries in America’s southernmost city.

Corcoran’s books have the added attraction of their setting. He gives us the underbelly of Key West, not just the tourist version. His books are fecund with sights, sounds and tastes of Key West.

As an even further added attraction: the setting, the heat, the lack of clothing, the island breezes . . . they all combine to make these Corcoran books sexier than your average detective novel.

I’ve read all of his books and his new one, The Cayo Hueso Maze, is his best. Again, you can start with this Alex Rutledge novel, then read the rest of them — and trust me, you’ll want to — in any order.

Corcoran was an Ohio boy, but was assigned to Key West in 1968, and he’s spent most of the last 50-plus years in the islands, and he knows the town’s deep history, having palled with Tennessee Williams, Thomas McGuane and Jim Harrison. He wrote a couple of songs with new-kid-in-town Jimmy Buffett (whom he also housed when Buffett lacked a place of his own) and co-authored two unproduced screenplays with Hunter S. Thompson.

(Of course, if you’re interested in Corcoran’s life, you can always read my swell book, Mile Marker Zero.)

We are in the middle of a global pandemic, so reading a Tom Corcoran book might be the only way to take a trip to the island.

Click on these links to buy the two latest books — Connelly’s The Law of Innocence and Corcoran’s The Cayo Hueso Maze.

Michael Connelly’s website: www.michaelconnelly.com

Tom Corcoran’s website: www.tomcorcoran.net