You’re never too old to be an orphan.

I lost my father when I was 20 and had just turned the corner to 60 when my mother died.

One would think, at such an advanced age, I’d no longer think of myself as a motherless child. Yet most mornings I woke, and would lie there a moment and reconnoiter with the world, remembering that I was alone.

And I was. My parents were gone and I was, as I say, untethered.

I had finished cancer treatment and found myself suddenly single. I was still defining myself as a solo act, concentrating on work during the week and managing the blossoming social schedules of three young teenage boys every weekend.

Life unfurls in unexpected ways. If ever there was a time to start over, this was it. God had given me another chance.

I’d had a lot of second chances.

Once, as a boy, I was playing at a construction site with some friends — it was a different time, kids — and I fell off a mound of moved earth and nearly down a bottomless (so it seemed to us) hole.

Another time, I fell backward off a swingset and banged my head on the concrete support that had uprooted from the ground. I was unconscious for nearly an  hour before I woke up in the emergency room.

hour before I woke up in the emergency room.

A man lunged in front of my car in a suicide attempt once on an Oklahoma Interstate, but I managed to disappoint him but nearly kill myself. Yet again I survived.

And how many times had I driven all night and fallen asleep, to be awakened by the road’s sudden change in texture and the sound of spitting gravel.

And now I’d had cancer. Note tense. To hear my surgeon and oncologist talk, I was cancer free. I always added “for now” in my head because I knew it was a long road. But if those guys were optimistic, that was a good sign.

Had they given me another chance, or had God? I wasn’t one of those people who’d gotten the diagnosis, then found God. I’d always believed in God — I’m from Indiana, where the license plate reads, “In God We Trust.” But I had not always practiced religion.

I’d had an ambivalent relationship with religion, which was a human construct. Though I grew up in a home with reverence, and been baptised a Methodist, we’d never gone to church and in adulthood I drifted toward Catholicism, mostly because I kept dating Catholic women. I converted at age 34, and for a period I was even a lector at our church back in Florida.

I’d had an ambivalent relationship with religion, which was a human construct. Though I grew up in a home with reverence, and been baptised a Methodist, we’d never gone to church and in adulthood I drifted toward Catholicism, mostly because I kept dating Catholic women. I converted at age 34, and for a period I was even a lector at our church back in Florida.

No matter my wavering attitude toward religion — and I often found myself on the apathetic end of the continuum — my belief in God did not flag nor fail, and I felt in debt.

What would I do with this second chance? I’d take better care of this thing, my body.

I met with Neil Ghushe and we contemplated another hernia surgery. He had just repaired a hernia not even a year before, using laprascopic technology to insert a screen in my belly on my left side. Now I had a hernia on my right.

That’s when I decided to call attention to the elephant hunched in the corner of his examination room.

“It’s because of my weight, isn’t it?” I asked.

He nodded, smiling. The guy had luminous eyes and a movie-star smile. If I’m ever due for some really bad news, I want him to deliver it.

“Could be,” he said, nodding. “Being overweight doesn’t help.”

“And walking hurts like hell,” I told him. “It’s like someone’s been hammering roofing nails into my knees.”

“It’s hard on your joints when you carry some extra weight,” he said. “No doubt about it.”

“And my sleep apnea. My wife used to say that if I’d lose 20 pounds — and I was always up and down on diets — but if I’d lose 20 pounds, my buzzsaw snoring would stop.”

“No doubt about it,” he nodded again. “Extra pounds exacerbate apnea.” He smiled and I felt the sudden urge to put on my shades; the glare, you know.

And that’s when the creature in the corner unrolled his massive trunk and began to bleat with the thunder of a thousand butterfly sneezes.

“What about that other surgery you do?” I asked. “Would I be eligible for that?”

Blinding smile. It’s like he was a surgical vampire — he needed an invitation. This isn’t something he’d bring up; he could only respond to my questions.

The “other surgery,” of course, was weight-reduction surgery.

I knew I fell into the “morbidly obsese” category because I weighed 20 pounds more than I should for my height. Hell, I was 60 or 80 pounds more than I should be.

I rarely used that other F-word, the one about weight. I felt that I was self-aware of my body and its myriad faults.

I rarely used that other F-word, the one about weight. I felt that I was self-aware of my body and its myriad faults.

But I also knew I was not grossly overweight. The kind of surgery Ghushe (it’s said goo-shay, by the way) did was for those extremely large people who couldn’t get out of bed or leave their houses.

But it was also for the rest of us who’d not taken care of ourselves and gotten into situations where the simplest walk was painful, whose guts could no longer be held in and who snored like a motherfucker.

Ghushe agreed to do the surgery and set in motion the approval process from my health insurance provider. Since it was likely that this surgery would solve those three chronic health problems and other yet-to-be-experienced maladies, it appeared to be a good investment.

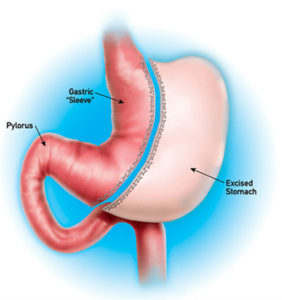

There were a lot of varieties of gastric surgery but Ghushe thought a sleeve gastroectomy was best for me. It would require removing 85 percent of my stomach so that I simply could not eat much at all. I grew up in that prosperous post-war clean-your-plate generation and I always did what I was told.

I liked sweets, but that wasn’t what made me gain weight. I had issues with portion control and sloth.

As I said, I was able to carry the weight well. I was overweight, but never looked can’t-leave-the-house overweight. If I’d told people my weight, they wouldn’t have believed it. I looked big, but not as big as I really was. I took only minuscule comfort in this.

Because I was overweight, I’d made myself into a wallflower — from junior high school on. I just avoided life because I worried about how I’d look doing what the other “normal” people did.

I thought I’d once been a normal kid. I played baseball pretty well and had a healthy bike-riding childhood.

One day my mother had company when I came in from an afternoon playing around the canals that ran though our South Florida air force base. When I came in for a glass of water, my mother introduced me to her friend. “My, what a husky young man,” the woman said.

I handled the minimum of courtesies then went outside and told my pal Paul Franks what the visitor had said. I wasn’t sure what it meant but it sounded grown up. And when you’re nine years old, you desperately want to be grown up.

“That’s not a good thing,” Paul said. “That’s not nice thing to say at all. It’s like she’s saying you’re fat.”

From that day forward, I began to think that’s how others saw me. My mother never talked about it.

Looking back on my school pictures, even up through high school, I see a kid that falls this side of overweight. With my aged eye, I see a kid who’d isolated himself because of a warped sense of self. I was not overweight, not really.

The weight came later.

Being a newspaper reporter was a mixture of a generally active life with long periods of sedentary work, because I doubled as a copy editor.

But I also began drinking in college — some nasty swill, like Strawberry Hill wine — and I began gaining weight.

And that’s when I started my up-and-down career as a dieter.

My first diet was a popular 1970s plan called the Stillman Diet. I drank 64 ounces of water a day and ate one meal – a geometic piece of ‘fish’ every day at 4 pm. Sundays, I’d go home to my parents’ house, do laundry and eat whatever I wanted.

I lost 60 pounds in six months. Once, years later, my brother was showing slides — we used those things then — of some family pictures. I saw a figure on the screen wearing a familiar T-shirt.

“Who’s that?” I asked innocently.

A beat. “That’s you.”

I could not reconcile that emaciated young man with the thick-middled man I had become.

For the next 40 years, there was a frequent weight fluctuation, driven by stress, goofy diets, and random spurts of exercise. Once a decade, it seemed, I’d get in reasonable shape — though I still saw myself as fat, no matter how much weight I’d lost.

The women in my life seemed to accept me as I was and if the issue of weight was raised, it was usually in relation to health.

One girlfriend urged me to try the grapefruit / high-protein diet, which I really liked. She also took walks with me four or five times a week, I was in great shape and she seemed to like my body. I dropped 60 pounds, again, But after five years, we broke up and I again fell into bad habits.

So here I was, post-cancer, grateful for another chance. I was in the downhill run and it was up to me to choose how I wanted to close out my life.

Did I want to be that man who groans walking upstairs, snores on the commuter rail, unable to keep up with the daily demands of life.

Fuck no, I didn’t.

I decided I would enjoy what life I had left, and to do that required something drastic.

I beheld the elephant on the other side of the examination room, and I felt kinship with the beast.