Welcome to the season of loss. I’ve lost some close friends recently. At this age, perhaps it’s expected, but that makes it no more welcome.

My friend Tom Corcoran has died. Let me tell you about this wonderful, generous man.

One morning many years ago, I awoke to an interesting message in my email inbox. “I put ‘Bob Dylan’ and ‘Hunter Thompson’ into Google and your name came up. Why?”

I told this unknown correspondent that I’d written books on Bob and Hunter and was, in fact, in the middle of writing another book on Hunter. He’d killed himself the year before and I wanted to write the first whole-life biography of Hunter Thompson. I wanted to talk about his work and the real man, whom I’d met years before and with whom I maintained an intermittent correspondence. To much of the world. Hunter Thompson was a drug-addled clown. I was revolted by that and sought to write a book that would focus on his art and craftsmanship.

So anyway — after the email from a stranger, then came the phone.

After several minutes of banter, Corcoran revealed that he knew Hunter well. He’d babysat Hunter during the time he lived at Jimmy Buffett’s Key West home in the late Seventies.

In return, Uncle Hunter babysat Corcoran’s young son, Sebastian. Hunter was reliable, if eccentric, caretaker. A bullhorn was essential to his surrogate parenting style. (For more details, read Outlaw Journalist.)

So now, years later, a pre-breakfast email and a phone call. A Potsdam conference was in order.

Corcoran lived squarely in the middle of Florida. I was upstate at the University of Florida, so I took a day off and made the two-hour drive to meet this guy.

Visiting Corcoran was like two middle-aged men having a play date. He had so much stuff – books, art prints, mementos – that he had two houses, side by side, to hold it all. I also discovered that in addition to a rich archive – this dude saved everything – that he had a steel trap mind.

While everyone around him had been snorting coke and getting drunk, Corcoran had managed to remain relatively clean and sober.

There’s no doubt that meeting Corcoran enriched my book. Historian Douglas Brinkley served as Hunter S. Thompson’s literary executor. After Thompson’s suicide, there had been a lot of books devoted to the iconoclastic writer. But Brinkley said my book stood out, in part because I was the only one to deal with the “missing years” of Thompson’s life in Key West.

All credit, of course, to Corcoran.

I was nearly finished with that book (Outlaw Journalist, available wherever fine books are sold) when Corcoran began telling me that I needed to write a book about Key West in the Seventies.

He even showed me a message from Thompson, dated less than two months before the suicide, suggesting that such a book must be written.

“Why don’t you write it?” I asked.

He was too close to it, he said. It needed to be written by someone on the outside. It needed to be me, he said.

It didn’t take a lot of convincing. I’d married a woman from Key West and both of her families went back several generations on the Rock. I had always wondered what a life hatched there would be like.

Yet my wife spoke of “getting out” of Key West, as if it was something bad, a place to be avoided. It was paradise, yes, but also dangerous.

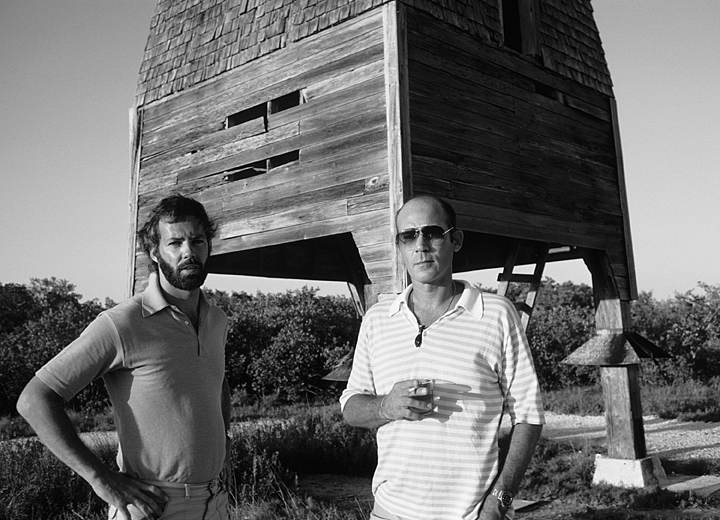

As I thought about that era and considered the writers working and playing in Key West, I began to see it as a parallel to Paris in the Twenties, when Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and the others redefined the landscape of American literature. Key West in the Seventies even had Thomas McGuane, the writer so often called the “new Hemingway” that he probably flinched at mention of the name.

Even before I’d read a book by McGuane, I knew who he was. Like Thompson, he was a writer so famous in his era that even people who didn’t read books knew who he was.

McGuane was portrayed as that drug-crazed new Hemingway they talked about in all the magazines, the one who was doing all that crazy stuff and getting married every 20 minutes or so down there in Key West.

That had been the public portrayal, at least. I’d seen what being a celebrity writer had done to Thompson. Yet I knew McGuane and his friends not only survived but prospered.

Whether that press portrayal was accurate or not, it intrigued me enough to want to know how McGuane, novelist/poet Jim Harrison, painter Russell Chatham and the others lived their lives.

I’d gone on to read their books and saw writing this book as an opportunity, among other things, to revel in their work.

I saw the potential of the story that Corcoran had told me. After generously giving me the idea, he stepped back. I think he had no interest in being the focal point of the book. That part was my idea.

That book, Mile Marker Zero, could not have been written without Corcoran’s monumental help, cooperation and steadfast kindness.

After Outlaw Journalist, I wanted to write a book with a happy ending. (Spoiler alert: Hunter Thompson kills himself at the end.)

I saw the Key West book as a redemption story. After earning fame as the greatest drug and alcohol user of his generation, Tom McGuane got sober. After being wed three times in 18 months — once to my dream woman, actor Margot Kidder — McGuane was thirty years into what he called a “jubilant marriage” with Laurie Buffett. (Yes, Jimmy’s sister.)

That was the story I wanted to tell. Redemption. A happy ending, on a Montana ranch.

But as I wrote the story, weaving together the adventures of McGuane, Harrison and Chatham, I realized it was really a book about Tom Corcoran and how he held together this world.

Over the years I’d worked on the books, I learned all about Corcoran’s life, including his marriage to Judy. They’d had problems — don’t we all? — but in his case, that relationship was unresolved. Judy went missing. She was with friends, sailing on a spectacular afternoon in the Keys. Everybody jumped in the water to take a swim. All were high.

They never found Judy.

So much for a happy ending. Before I turned the manuscript into the editor, I sent it to Tom, for fact-checking and editing suggestions. Corcoran was a brilliant writer and when he gave me a compliment — “You write like a pro, Bubba” — it made my heart soar like a hawk (Apologies to Thomas Berger for that one.)

When he read the section about Judy, he was taken aback. He’d told me the story but didn’t think it would be in the book. I was ashamed of hurting him and said I’d take it out.

“No,” he said. “That’s part of the story.” This was followed my a long sigh. I offered again to take it out but he said the story was mine to tell.

We remained friends. When I was in cancer treatment, he sent me messages of support … and some good books.

He died of cancer, but we never knew he was sick. It wasn’t like him to share his pain. I have two extremely wonderful big brothers (one’s a brother in law, but he’s been in my life since I was 9.) But Corcoran was a big brother to me. I admired him so much.

I wanted to be like him when I grew up. To quote Paul Simon, “Who’ll be my role model now that my role model is gone?”

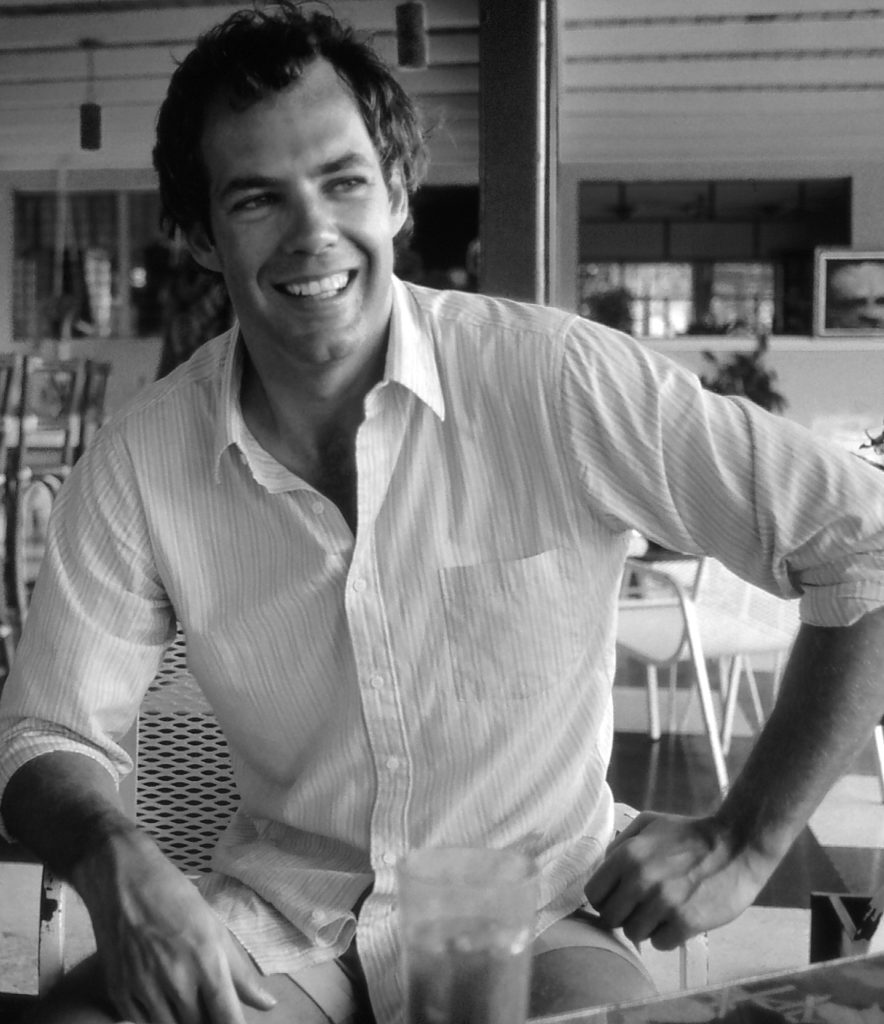

Perhaps I ramble, so let’s gather the facts: Tom Corcoran has died. He was gifted as a writer, a photographer, a songwriter, a pal and a human being. He touched so many people and we all loved him.

Maybe I should just end this with the ending of Mile Marker Zero — one of our nights together, when we went out to dinner and had another evening of spectacular conversation.

Here:

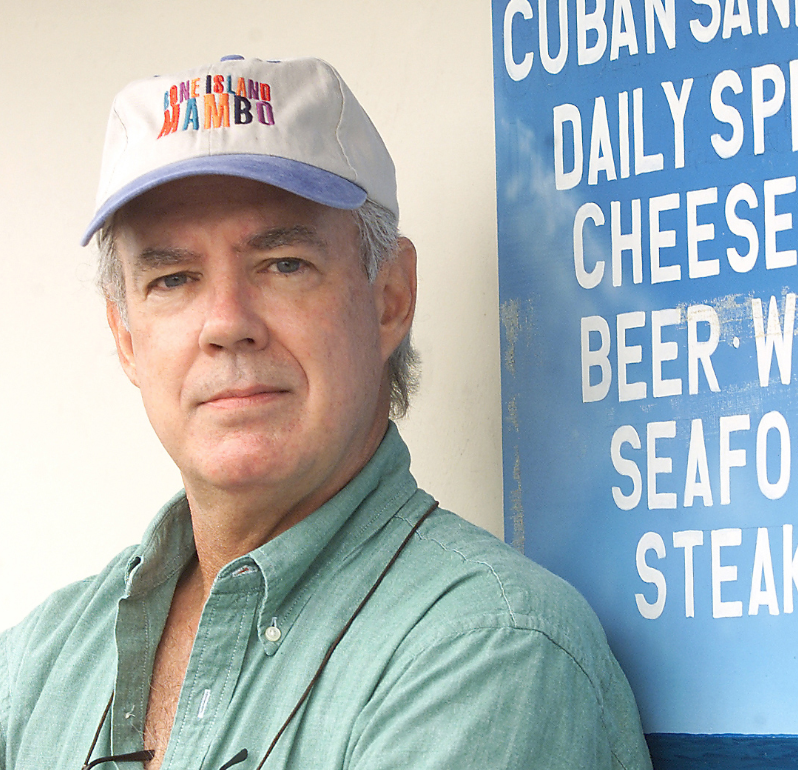

Tom Corcoran now owns two houses, side by side, in a central Florida town at the outer reaches of Orlando’s gravitational pull. His adult son, Sebastian, lives in one, presiding over Corcoran’s huge, moody Russell Chatham lithographs and some of the artifacts from his life and career. Corcoran lives a few steps across the manicured yard in the house he reserves for his other possessions – a magnificent collection of books, more lithographs, more of his beautiful photographs of a golden age of Key West.

Corcoran sleeps here.

It’s hard to find a seat. The place is more warehouse than home. It is also where Corcoran works. There are no couches, no tables, no bar stools. The dining room holds most of the inventory for his small publishing business, The Ketch and Yawl Press. More books and boxes of Jimmy Buffett calendars, another Corcoran enterprise, fill the living room.

There are two chairs in the larger of the three rooms devoted to his library. One is a remnant from Buffett’s Waddell Street apartment. Corcoran could put a plaque on it and sell it to the Hard Rock Café: “Jimmy Buffett Sat Here.” It could also say, “Tom McGuane Sat Here” or “Hunter S. Thompson Sat Here,” but so far, no one has devised a theme restaurant built around literature.

In the office, where Corcoran writes his novels, there is a desk chair and a small chair for visitors, usually covered in piles of manuscript pages.

Tom Corcoran was long ago priced out of Key West, and lived in Fairhope, Alabama, for several years. Eventually, he found work writing about automobiles and became editor of a magazine about the cult surrounding the Ford Mustang. That job brought him back to Florida and he settled smack dab in the middle of the state this time. He published three books about cars, but knew it was time for him to realize that long-dormant ambition to be a novelist. His muse, of course, was Key West.

He couldn’t afford to live there, but when he left the magazine job, he moved to the Keys in the Nineties, buying a home on Cudjoe and finally beginning to write the novels he’d always planned to write. They were mysteries set in Key West, built around a photographer who knew the island and all of its history. The character, Alex Rutledge, gets pulled into solving crimes.

“How much of Alex Rutledge is Tom Corcoran?” a visitor asks.

“Quite a bit,” he says.

In his fiction, he’s dealt – tangentially, mostly – with a lot of the real mysteries of Key West, including the disappearance of Bum Farto. He has not, and will not, write about the disappearance of Judy Corcoran. That would cause a raft of pain.

When his first novel, The Mango Opera, was published, his friends lined up to praise his books with dust-jacket blurbs that would be the envy of any American writer: Tom McGuane, Jim Harrison, Hunter S. Thompson, Jimmy Buffett. He became one of the best mystery writers in America. Though he does not sell books by the truckload, as does a Michael Connelly, he earns the praise of such masters of the craft. Connelly called one of Corcoran’s books “the reading highlight of my year.”

He gave up the Cudjoe Key house some years back and now shares the twin houses with Sebastian. He goes to the Keys a half dozen times a year, usually staying with Dink Bruce. He also writes songs with John Frinzi and Keith Sykes. He still collects a handsome royalty each year for a few minutes of collaboration with Jimmy Buffett three decades ago.

Out at dinner, he is kind and solicitous to his young waitress. The talk turns to music and Corcoran’s dinner companion tells her, “This dude wrote songs with Jimmy Buffett.”

“Really?” she asks. Though he’s grandfather age to her, you can see that celebrity remains a powerful aphrodisiac.

“Not only that,” the companion says. “He once wrote a movie with Hunter Thompson. And he’s a big-time mystery writer.”

“Really?” It’s drawn out three or four extra syllables.

It’s dark in the restaurant, so it’s not clear if Corcoran is blushing, but the smart money is on it.

He tells her a few stories about Buffett and Thompson in the old days in Key West. She’s smiling, ignoring all of her other tables.

“I’ve never been,” she says. “Key West, I mean. I’ve lived in Florida my whole life, but I’ve never been.”

“You should go.” Corcoran’s matter of fact, serious even. “It’s not what it was in my day, but you should still go.”

She smiles.

“I can’t finish this,” he says, nodding toward his plate. “Could you bring me something to pack it up in?”

“Yes, sir.”

Back at his house, he’s getting out of his car when he hears a hello as a bicycle speeds past in the dark. It’s Sebastian, home from an evening with friends. Corcoran walks over to his other front yard.

“Hello, Son,” he says. “I couldn’t eat all my dinner. Would you like it?”

“That’d be great,” Sebastian says. “I haven’t gotten around to eating yet.”

“It’s Italian. It’s good. I just wasn’t that hungry.”

“Thanks, Dad.”

Corcoran turns back toward his other house. “Goodnight, Son.”

“Good night, Dad.”

But Corcoran isn’t ready for bed just yet. If he didn’t have a visitor, he might be at work on his next Alex Rutledge novel. Instead, he looks through his files of photographs of Key West. He’s published one book, a limited-edition art book, of black and whites. Now he’s contemplating a companion book in color.

The photographs are sharp and vivid, not faded and blurred with time. Corcoran examines each one carefully, seeing occasional flaws, remembering the instant each photograph was taken.

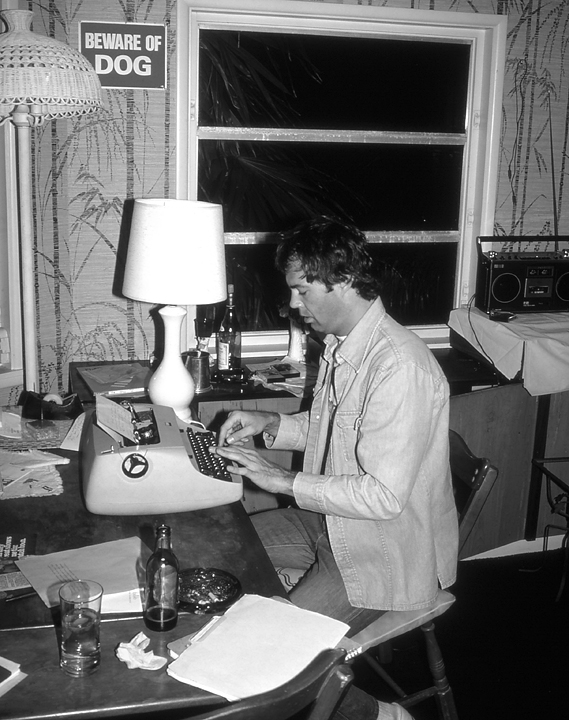

Here’s McGuane, serenely high from the look in his eyes, with Richard Brautigan and Guy de la Valdene. That was on Duval, he thinks. Here’s Hunter S. Thompson, probably in 1978 or so, looking over a manuscript page in Buffett’s apartment, sitting in that chair that’s in the next room. And speak of the devil, here’s a young and hairy Jimmy Buffett, wearing the smallest of cut-off shorts, hanging off the side of his sloop.

Must’ve been 1974 or thereabouts. He wasn’t the multi-millionaire entrepreneur then, but aside from the hairline and the income, Corcoran isn’t sure all that much has changed.

He treats everything with surgical care: photographic prints are in plastic slipcases; valuable books have mylar covers. He has a whole bookcase devoted to his Key West collection, many of them rare, precious and beautiful.

You should turn this into a museum, the guest says.

He nods. “Perhaps I will.”

It’s well after midnight when he finally puts away the pictures and announces he’s ready for bed.

He locks the front door, turns out the lights, crosses the hall to his bedroom, and gets between the covers.

Thinking about Key West again invigorates him, but he’s tired, so he falls asleep quickly, slipping into a dream before very long. Soon, he could see the blue water.