My book was called Outlaw Journalist in the English-speaking world. The title was a little more cumbersome in French. I saw that a review of the book appeared in a French publication, so I copied and pasted it into Google Translate and this is what I got. I particularly like the phrase “monkey emeritus.”

Hunter S. Thompson was the inventor of gonzo style: journalism written by a living pharmacy, a way to crack the American dream without skimping on LSD, peyote, Tequila, Chivas Regal and other amphetamines, a columnist who is featured as the character Principal’s reports.

The excellent biography by William McKeen does justice to this monkey emeritus.

The monster was born in 1937 in Louisville, Kentucky, a city providing half the world’s bourbon. Adept of creative vandalism, the juvenile seeks to silence his demons by engaging in the Air Force. Editor of a cabbage leaf for sport pilots, it is already the bombing and the chameleon. He was fired in 1957 for “rebel and superior attitude.”

Here grouillot to Time columnist bowling Puerto Rico goalkeeper villa in Big Sur, freelance for The Observer in Latin America. Adept of hitchhiking in bermuda, the character loves shooting rats with a 357 Magnum. Reader Hemingway at the time of Bob Dylan, this atypical madmen consonant with a new generation of columnists. They call Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, Terry Southern. Their way? Integrating the psyche of a journalist in the article itself, deal with the real weapons of fiction. In this new journalism, Thompson adds a kind of intimate caving with whims and exciting. Set in 1964 in San Francisco, he lives between the world of psychedelic hippies and the leather community while the Hells Angels, which he dedicated in 1967 an essay memorable him to be beaten by those crazy bikers. “Journalism, he said, pays for our continued education.

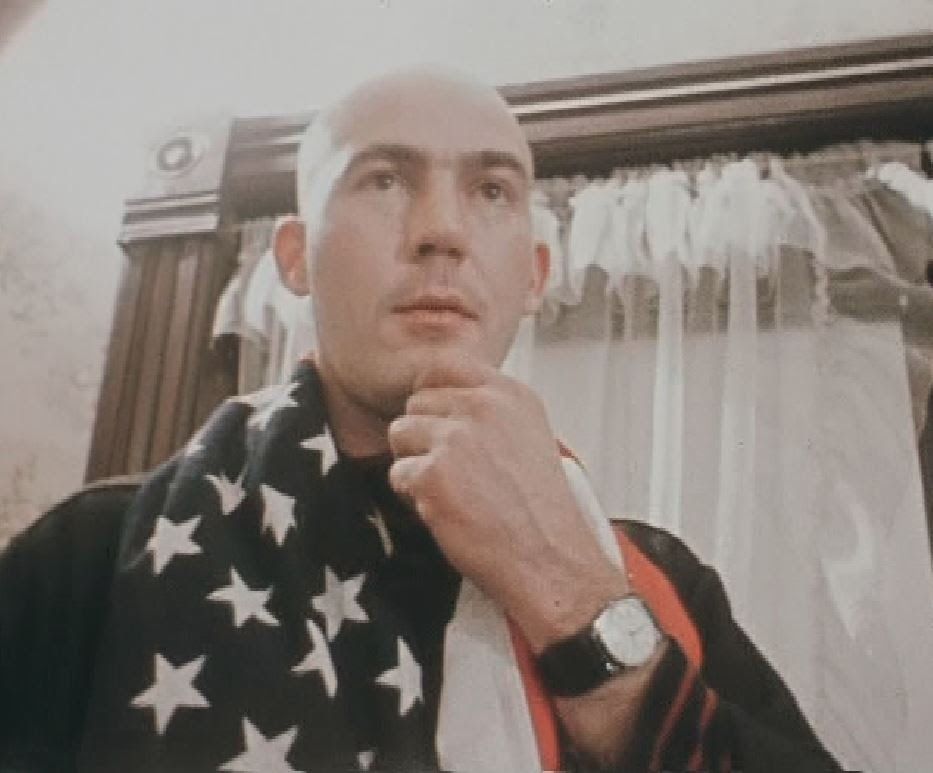

Now camped in his hut in Aspen, Thompson throne with his eternal cigarette holder and his Hawaiian shirt in the woods elk stolen Hemingway. Looks like a kind of Walt Whitman redesigned by Robert Crumb. The brilliant crazy wrote to President Johnson asking him to be appointed Governor of Samoa before embarking on one of his terrible raids journalism. Will pay for the presidential candidates of 1968: Richard Nixon, his staff Antichrist, “a nightmare of intrigue, bullshit and suspicion”, and his rival Humphrey, “an ignoble body electrified.

“Hunter did not commit suicide, Hunter followed the Way of the Samurai” (Iggy Pop)

Freak. Described by one witness as “a cross between half-mad hermit and a Tasmanian devil”, this psychotic Celinian is recruited by the fledgling Rolling Stone magazine, which he made the beautiful days. There he publishes Loathing in Las Vegas, the story of a drift distorted through the game city, wrote to the Dexedrine and bourbon during the summer of 1971. Journalism vision, stretched, torn by lightning psychotropic, as if the Stones put music in the Apocalypse of St. John. The legend of gonzo Thompson begins to take shape. The man, safari hat covers the presidential campaign of 1972 or the fall of Saigon, and sometimes signed “Martin Bormann” on hotel registers, becomes a character in the comic strip Doonesbury Uncle Duke, a reporter with the glasses of ‘Aviator seeing bats everywhere.

After 1976, Thompson patina. Cocaine him gnawing nostrils. His wife Sandy left him. He was fishing for tarpon in Key West, is the portrait of Muhammad Ali, hangs out with Jim Harrison or John Belushi, then resumed a weekly column in the Examiner. Working in his kitchen in the middle of televisions turned on, the super-freak of the Reagan gently invite to vote for Bill Clinton, whom he lent “the loyalty of a lizard who lost his tail.” The man who loved to “dedicate” his books with a bullet becomes the totem of young Hollywood, revered by Sean Penn or Johnny Depp, who will play in the film Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. But, less a prisoner of his mythology, the old hunter scalps in 2005 will choose the end of Hemingway’s heroes: a .45 caliber gun in his mouth. “Hunter did not commit suicide, Hunter followed the Way of the Samurai,” says Iggy Pop. Consistent with this life pyrotechnic is the gun that his ashes were eventually scattered.

Hunter S. Thompson: journalist and off-the-law, William McKeen (Tristram, translated from English by Jean-Paul Mourlon, 496 p., 24 euros).

Hunter S. Thompson