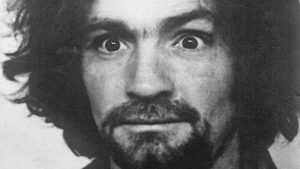

When Charles Manson was a boy, his mother traded him for a pitcher of beer. He was fetched home by an uncle and returned to his mother, who merely shrugged. She was a prostitute and a small-time thief who passed trade secrets to her son.

Manson was jailed for the first time at 13, for burglary. By the time he was in his early 30s, he’d already spent half his life behind bars.

As he was being released from California’s Terminal Island prison in 1967, he panicked and asked the jailer not to turn him out into the world. The guard laughed, but Manson was serious. Prison was the only real home he’d known.

When the lifelong con man hit the streets, much had changed since 1960, the year he had last tasted freedom. It was the Summer of Love and Manson drifted to San Francisco, epicenter of America’s cultural revolution.

There he found docile flower children — easy marks, even for an inept crook. He adopted the hirsute look of the tribe, recycled some of the Scientology babble he’d picked up in the joint, and started building a “family” of followers drunk on his flattery. He preyed on lost and damaged young women — wounded birds — and made them think they were beautiful, as long as they followed him.

He sought fame. He deserved fame, he reasoned, and he needed to make the world notice him. “His followers had no idea that Charlie was obsessed with becoming famous,” biographer Jeff Guinn wrote. “He told them that his goal, his mission, really, was to teach the world a better way to live through his songs.”

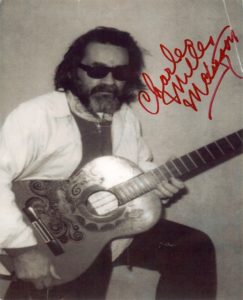

He figured the fastest route to fame was through music. He knew a few chords and could reasonably mimic the peace, love and flowers ethos in his lyrics. If he looked the part and acted the part, he could bask in the fame he felt he was owed.

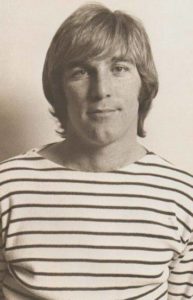

He brought his “family” of damaged goods to Los Angeles and sent his women to scout for men who could either help Charlie find fame or money. While hitchhiking one day, a couple of the girls found an easy mark: the big-hearted, generous and sex-obsessed drummer for the Beach Boys, Dennis Wilson. He picked them up, took them home for milk, cookies and sex, then left for a recording session. When Dennis returned home in the middle of the night, the girls were still there, along with Charlie Manson and 15 other young women, all mostly nude. For a sex junkie like Dennis, it was paradise.

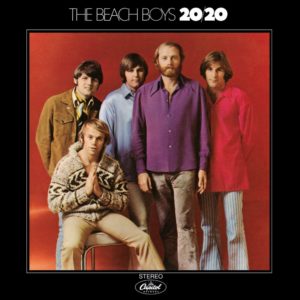

Manson saw Dennis — and his Beach Boy brothers Brian and Carl — as his entrée to the music business and international fame. Although the group’s star was dimming by the late ’60s — they were no longer the hip boy band they had once been — it was at least a moccasin in the music industry’s door. Through his time as Dennis Wilson’s roommate, Charlie had gotten to know record producer Terry Melcher, Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas, Neil Young and Frank Zappa.

Convinced he would make Charlie — whom he called the Wizard — into a star, Dennis urged his brothers to record the fledgling singer at the Beach Boys studio in Brian Wilson’s home. Wherever Charlie went, of course, his “family” followed. Marilyn Wilson, married to Brian at the time, had the bathrooms fumigated after every session, fearing the filthy girls were spreading disease. (And they were, though not the kind that showed up on toilet seats. Dennis ended up footing, for the Manson women, what was jokingly referred to as the largest gonorrhea bill in history.

When Dennis’s efforts bore no fruit, Manson glommed onto Melcher, who had produced the Byrds and Paul Revere and the Raiders. Melcher and Wilson introduced Manson to L.A.’s music society, largely through lavish parties at the estate on Cielo Drive that Melcher shared with actress Candace Bergen. At Cass Elliot’s parties, Manson played whirling dervish on the dance floor, entertaining all with his spastic monkey moves.

When Neil Young heard Charlie sing his compositions during a drop-in at Dennis Wilson’s house, he called Mo Ostin, president of Warner-Reprise Records, to urge the boss to give the guy a listen. Young warned him that Charlie was a little out there and spewed songs more than sang him. But still, Young insisted there was something there.

And there was. Manson’s voice was good enough that he had a reasonable expectation of getting a recording contract. His original compositions were good enough to be recorded: The Beach Boys adapted one of his songs into something called “Never Learn Not to Love,” which they performed on the supremely wholesome “Mike Douglas Show.”

Manson’s lyrics, unfortunately, were mostly honky gibberish, bad enough to justify Ostin’s rejection and for Melcher to tell Charlie he couldn’t get him the record contract he so desperately wanted.

But it was too late to stop now. Charlie had drunk from the trough of fame. He mingled with rock stars and thought he was entitled to be a rock star.

The American Dream used to be described thus: Come to America with nothing and, with the great freedoms and opportunity offered by the country, exit life with prosperity. It has also been described as simply the ideal of freedom — of living in a free and robust society, with nothing to impede people but an open road.

At some point, this changed. In the post-war world of abundant leisure and instant gratification, an ethos of opportunity, hard work and the gradual accumulation of wealth fell away, replaced by a longing for instant fame and fortune. Perhaps it was a result of the conspicuous wealth so visible on the new medium of television. Maybe these new celebrities burned so much brighter because their images slipped through the cathode ray into millions of American homes, turning the house into the new movie theater.

Either way, for millions today, the American Dream is simply the delirious pursuit of fame. Ask a school child what he wants and it’s simply to be famous — by any means necessary.

Charlie Manson was an early avatar for this new concept of the American Dream. He sought fame at any cost. He tried to achieve celebrity through music and, when he didn’t reach that goal, he turned to crime. Sure, he would spend 61 of his 83 years in prison. But the cameras rolled, the papers were printed, the books were sold. No one would ever forget his name.

Manson achieved his goal, becoming so famous that his name replaced those of his victims. The crimes became known as the Manson Murders.

Look to the media today to see Manson’s ideological descendants, thirsting for fame at any cost. Some don’t just risk humiliation, they court it. Remember the early rounds of “American Idol” with jarringly dreadful performances giving the reprehensible “singers” their 15 seconds of fame?

Other, more deadly offspring, could be the boys who shoot up schools and coffee shops and prayer-group meetings. They might be dead, they might have left a trail of destruction in their wake and they aren’t mourned. But like Manson, they are remembered. That’s certainly more than most failed con men can claim.

Unfortunately, Manson achieved his goal: fame. Perhaps the best way to honor his victims is to forget his name.

Recommended reading: I don’t reference it in this piece, but I’d like to mention a great book by Ed Sanders called The Family (Dutton, 1971). This was one of the most important books in my life — not because of Manson, but because it made me want to be a writer. I know the book has had the same effect on a lot of other people. Of course, any dive into literature about Manson includes Helter Skelter (WW Norton, 1974) by Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry. Jeff Guinn’s biography, Manson (Simon and Schuster, 2013) is superb.