Sometimes, I feel as if I am on dead-rock-star speed dial.

Ever since publication of Rock and Roll is Here to Stay a quarter century ago (and which you can order here), I get calls from reporters before the body gets cold.

And sometimes, the body is still warm.

After Hurricane Katrina, I got a lot of calls from journalists putting together obituaries. Problem was, Fats Domino wasn’t dead yet. He was rescued from the attic of the house where he’d hunkered down. (Or, considering he was found in the attic, let’s make that hunkered up.)

When Maurice Gibb of the BeeGees died, I was happy to talk about the beautiful harmonies those Gibb brothers spawned. Yet the AP reporter didn’t quote my comment on what I thought was one of the singer’s greatest achievements (“He fought a valiant battle against a receding hairline.”)

When Brian Wilson died earlier this month, I missed the call from the BBC and by the time I returned the message we’d passed another full news cycle. I’m not as diligent about responding during the summer.

The Los Angeles Times didn’t call me, but quoted me anyway. In this piece, they had me saying something I have no memory of saying and affiliating me with the University of Florida, with which I have not been affiliated for 15 years.

It’s just as well that no reporters reached me, since I was blubbering like a baby.

It was a huge loss to the world of music and to my life. Brian has been a part of my world for decades.

All right, I wasn’t really crying. At least I was lucky to get the news from my pal and fellow Brian Wilson believer, Wayne Garcia. Wayne named his firstborn Brian. I’ve never gone that far, but that’s mostly to avoid saddling a child with “BM” for initials.

Brian was the only Beach Boy I never interviewed. In my Saturday Evening Post days, my mentor Starkey Flythe and I collaborated on a profile of the band for the magazine. “The Endless Summer of the Beach Boys” was credited to Samuel Walton, one of Starkey’s pseudonyms. (A plethora of pseudonymns gave readers the impression the magazine had a large staff. This was a time, my friends, before the world at large had knowledge of Walmart and its founder, with whom we shared that pseudonymn. Starkey also masqueraded as F.X. O’Connor. I liked the pen name Captain Asparagus, which I’d seen in a local zine.)

Starkey and I followed the Boys through a couple of gigs to get material for the story.

During the stay in Cincinnati on their annual summer tour, we had dinner with Mike Love and his wife. Mike is a divisive figure with fans, but all I can say is that he was a charming dinner companion, even if he did not accept my revised “California Girls” lyrics for my proposed “Prehistoric Girls:”

Well, neanderthal girls are hip, I really dig the skins they wear

And the cro-mangon girls, with the way they stalk,

They knock me out when I’m down there

The Midwest savages’ daughters really make me feel all right

And the Mayan girls, with the way they kiss,

They keep those temples warm at night

I wish they all could be prehistoric girls

Mike gave me a hard pass. (And yes, I know I am bending science history to put together this paean.)

(Later, in the 1990s, I thought about sending Mike new lyrics to be paired with the “Catch a Wave” music: Get your keyboard and go internet surfin’ with me. The scary thing is, Mike might’ve gone for that one.)

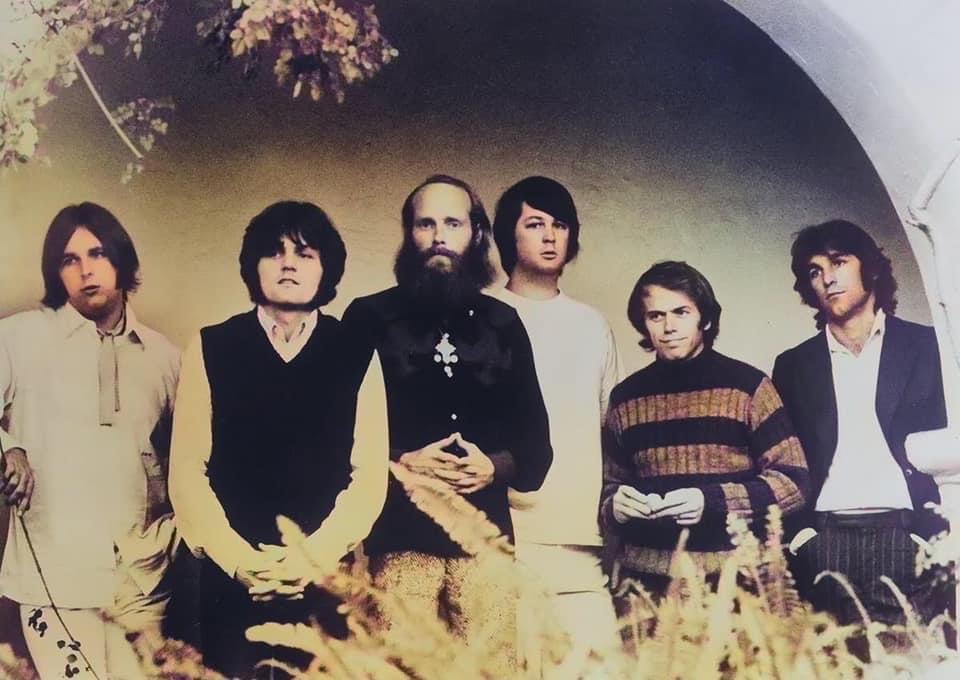

We had a great afternoon interviewing Carl Wilson and Alan Jardine. I still have a song in my head that Jardine was writing about polypeptides. (This was in the days when the Beach Boys were uber-creative, before they were doomed to life as an oldies band.)

Dennis Wilson did not want to be intervewed but asked us to his room to watch TV, then ride with him to the concert venue, Cincinnati’s Riverfront Colliseum. He was a wonderful guy. I ended up interviewing him three times over the years and he was always enchanting and hilarious. He was generous with his time and talent.

I never interviewed Brian, but perhaps that’s just as well. Starkey interviewed him when he was on the West Coast for another assignment. He said it was the weirdest interview he’d ever done. Brian was in his chain-smoking 340-pound period.

Starkey told me he’d mentioned me to Brian.

“Brian,” he said by way of introduction, “I bear greetings from your biggest fan.”

“Who’s that?” bathrobed Brian growled.

“Bill McKeen.”

Brian pondered for a minute, searching the fulsome settlings in his brain. “Never heard of ‘im.”

I have been a Beach Boys fan for nearly 60 years. I discovered them during that lost period after their initial fame and before they were rediscovered as an oldies act.

If you truly love the Beach Boys, then they drive you crazy. You know they are / were capable of greatness. And you also know they can / did produce some sub-par stuff.

Years ago, a writer for the Florida Times Union in Jacksonville wrote something like this:

We can put a man on the moon, but we can’t stop people from wearing spandex pants to the mail. The Beach Boys will drive you crazy that way.

I wish I had kept that artice so I could acknowledge the writer and get the quote right.

I hardly ever listen to the early Beach Boys stuff, much as I liked it. Yet when I learned Brian died, my hand — working independetly from my brain — reached into my record bin for All Summer Long (1964).

Some of those early albums (OK, Shut Down Vol. 2, All Summer Long and Today) were marred by needle-lifting skits that I despise. At least the one on All Summer Long is kind of funny.

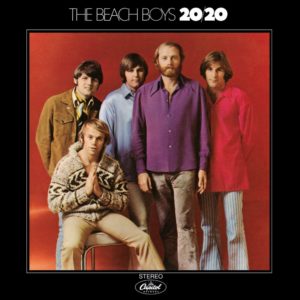

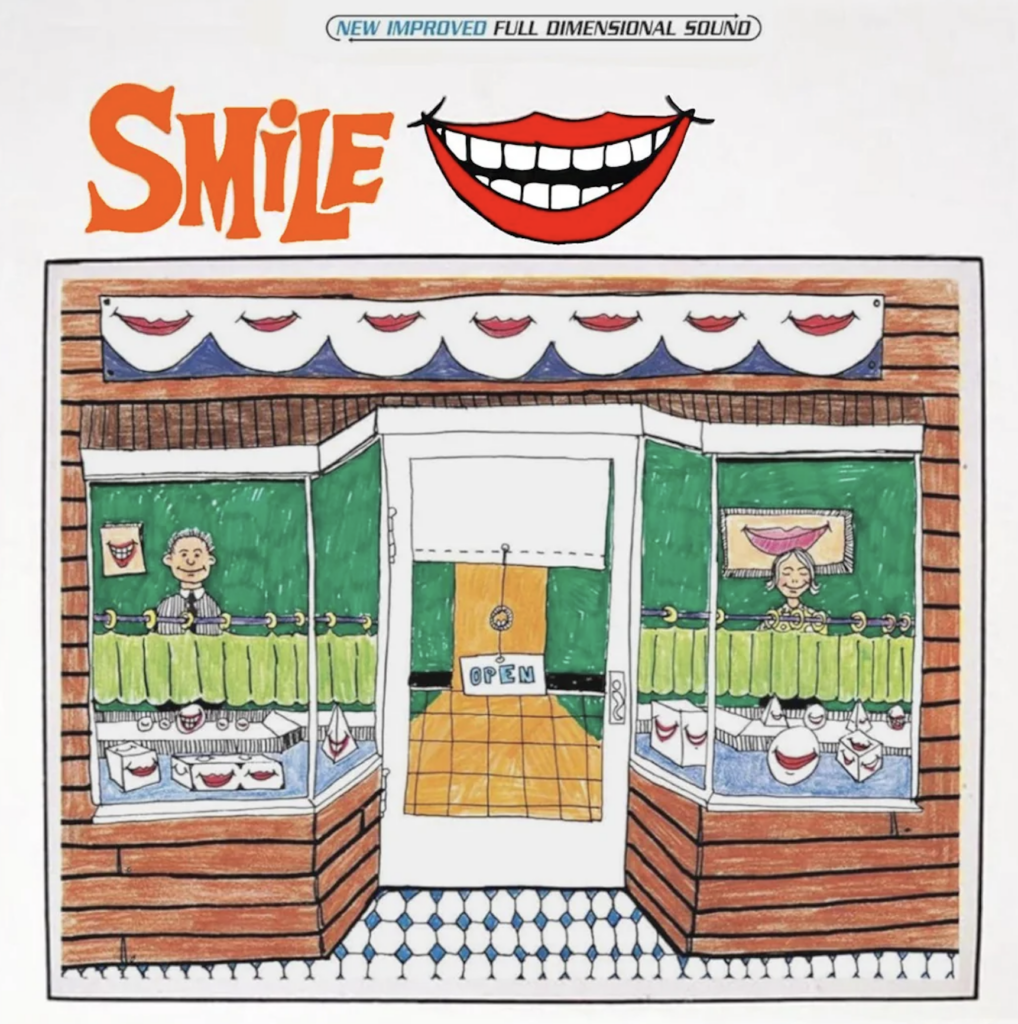

I prefer the albums of the “lost years,” after the huge early fame and after Brian’s magnum opus, Smile, went down in flames (which he resurrected in 2004). Those albums were all commercial flops but they remain pure and beautiful healing music: Smiley Smile and Wild Honey (both 1967), Friends (1968), 20/20 (1969), Sunflower (1970), Surf’s Up (1971) and Holland (1973). I leave out only So Tough (1972) because that album was a mixed bag — and short. (In my old age, I’ve grown to appreciate it more.)

So when I feel like listening to the Beach Boys, those albums are the ones I reach for. The band’s last album, That’s Why God Made the Radio (2012) had some of the most sublime moments in the group’s history. The last three songs on the album are heartbreakingly beautiful. The last song on their last album was, appropriately enough, called “Summer’s Gone.” It was grandly depressing and majestic.

I have reverence for Pet Sounds (1966). Listening to it is often difficult for the emotions it churns up. It has been an indelible part of my life since I was in a teen-ager with an 8-track in my Opal, with Pet Sounds on a continual loop. That tape stayed in the player for a year, and I heard the album so much it seeped into my sinews. Kind of like Steve McQueen in The Blob: this thing absorbed me and became part of my essence.

The album is so good that I can’t listen to it. It takes too much out of me.

Plus, I don’t have to listen to it. Every vocal, every note, every banjo strum, every drum bash, every belching tuba and barking dog is stored in my head.

There’s a lot to be said about Brian. He had an odd (no surprise there) solo career that included the occasional brilliant piece of original work — That Lucky Old Sun (2008) — and intriguing albums devoted to George Gershwin and Disney music.

The Wilson brothers are all gone now. To me, the Beach Boys ceased to be when Carl Wilson died in 1998. With no Wilson onstage, there were no Beach Boys. What’s out there on the road is Mike Love with a very good (I’m told) Beach Boys tribute band.

So. Brian is gone.

We toil in melancholy, but as Brian’s music often helped me to do, I find some kind of joy inside the sadness.

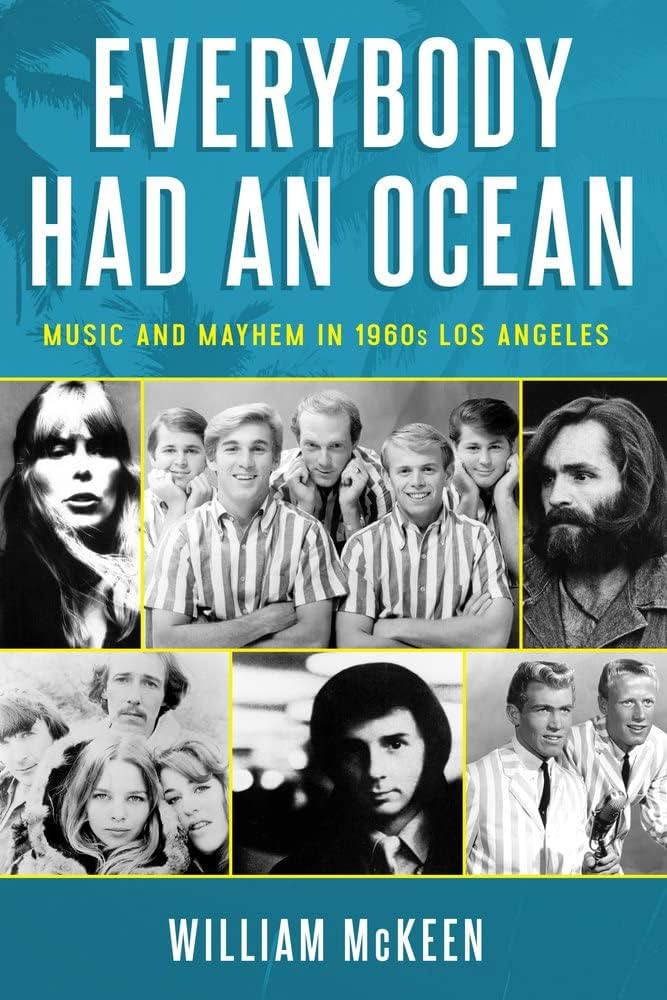

I used the Beach Boys to frame my story of Los Angeles music in the 1960s, Everybody Had An Ocean (which you can order by clicking on the cover at left) and here’s how that book ended:

“Creating art allows us to beat the odds and find immortality, without having to do the whole Doctor Faustus thing. Though Brian Wilson and Mike Love no longer collaborate and Carl and Dennis Wilson are gone, they are all still together on the radio late at night, where they join voices and are young and golden and beautiful forever.”

And now, for fun, here are my favorite Beach Boys songs in chronological order. I realize no one gives a shit about this, but I like to amuse myself.

You will note the absence of “Kokomo” on this list. This is not an oversight. Brian was in California and was told about the “Kokomo” session in Atlanta only 24 hours before the studio was scheduled. He was unable to make the session. Brian was also absent from the recording of “I Can Hear Music” in 1969. That was during a rough period when he had trouble engaging with the human race, and marked sort of a changing of the guard. The Master (Brian) had taught his young grasshopper (Carl) well.

Both “Kokomo” and “I Can Hear Music” feature Carl’s angelic voice. It was funny to see the flurry of posts by fans after Brian’s death. Seems like everyone posted “Kokomo,” a song on which he did nothing.

So here is my list, though no one outside a lunatic asylum cares about this:

1962: “Surfin’ Safari.”

1963: “Surfin’ USA,” “Farmer’s Daughter,” “Shut Down,” “Surfer Girl,” “Catch a Wave,” “The Surfer Moon,” “In My Room,” “Our Car Club,” “Boogie Woodie,” “Little Deuce Coupe,” “Car Crazy Cutie” (musically identical to “Pamela Jean”), “Cherry Cherry Coupe.”

1964: “Fun Fun Fun,” “Don’t Worry Baby,” “The Warmth of the Sun,” “This Car of Mine,” “Why Do Fools Fall in Love,”* “I Get Around,” ” All Summer Long,” “Hushabye,”* “Little Honda,” “We’ll Run Away,” “Wendy,” “Don’t Back Down.”

1965: “Do You Wanna Dance?,”* “Good to My Baby,” “Don’t Hurt My Little Sister,” “Dance Dance Dance,” “Please Let Me Wonder,” “I’m So Young,”* “Kiss Me Baby,” “In the Back of My Mind,” “The Girl From New York City,” “Girl Don’t Tell Me,” “Help Me Rhonda,” “California Girls,” “You’re So Good to Me,” “The Little Girl I Once Knew.”

1966: “Wouldn’t it Be Nice?,” “You Still Believe in Me,” “Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder),” “I’m Waiting for the Day,” “Sloop John B,”* “God Only Knows,” “Caroline No,” “Good Vibrations.”

1967: “Heroes and Villains,” “Vegetables,” “Little Pad,” “Wind Chimes, “Wonderful,” “Wild Honey,” “Darlin’,” “Aren’t You Glad,” “I Was Made to Love Her,”* ” Let the Wind Blow,” “Mama Says.”

1968: “Friends,” “Wake the World,” “Little Bird,”** “Be Still.”**

1969: “Do it Again,” “I Can Hear Music,”* “Cotton Fields,”* “I Went to Sleep,” “Time to Get Alone,” “Our Prayer,” “Celebrate the News,”** “Cabinessence.”

1970: “Their Hearts Were Full of Spring,”* “Slip on Through,”** ” This Whole World,” “Add Some Music to Your Day,” “It’s About Time,”** ” Forever,”** “All I Wanna Do,” “At My Window,” “Cool Cool Water.”

1971: “Long Promised Road,”*** “Feel Flows,”*** “‘Til I Die,” “Surf’s Up.”

1972: “You Need a Mess of Help to Stand Alone,” “Marcella,” “All This is That,” “He Come Down,” “Cuddle Up.”**

1973: “Sail On Sailor,” “Steamboat,”** “California,”# “The Trader,*** “Only With You,”** “Funky Pretty.”

1976: “Palisades Park,”* “In the Still of the Night.”*

1977: “Mona,” “Johnny Carson,” “Good Time,” “Honkin’ Down the Highway,” “The Night Was So Young,” “I’ll Bet He’s Nice,” “I Wanna Pick You Up,” “Airplane.”

1978: “Sweet Sunday Love.”

1979: “Good Timin’,” “I’ll Be in Heaven When My Angel Comes Home,”*** “Love Surrounds Me,” ** “Baby Blue.”**

1980: “Goin’ On,” “Sunshine,” “You Are So Beautiful.”**

1981: “San Miguel.”**

1985: “I’m So Lonely.”

1986: “California Dreamin.’ “*

1993: “Fourth of July.”**

1998: “Soulful Old Man Sunshine,” “Loop De Loop,” “Sail Plane Song,” “Barbara.”**

2001: “Their Hearts Were Full of Spring,”*. “Devoted to You.”*

2012: “That’s Why God Made the Radio,” “Isn’t it Time,” “From There to Back Again,” “Summer’s Gone.”

2013: “Fallin’ in Love,”** “Wouldn’t it be Nice to Live Again.” **

All songs by Brian Wilson, usually with a collaborator (or two). The exceptions are (*) songs written by people outside the group. Other songs written by (**) Dennis Wilson, (***) Carl Wilson and (#) Alan Jardine.

These are in order by release date. “San Miguel,” for example, was recorded in 1969-70, but not released until 1981. “Fallin’ in Love,” another Dennis Wilson gem, was recorded in 1971 but was left off of Surf’s Up (one wonders why) and did not appear on a Beach Boys album until the Made in California anthology in 2013.