We are dealing with the second anniversary of David Carr’s death. There were so many tributes after this death, so maybe this ‘last interview’ (with Stefanie Friedhoff of the Boston Globe) got lost in the mix. Thought I’d reprint it. We were lucky to have David on the Boston University faculty. He was a gifted teacher and we all looked forward to many years of his friendship. This was published February 13, 2015.

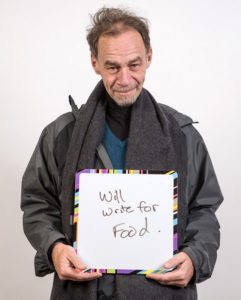

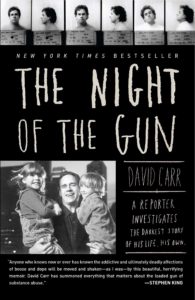

New York Times columnist David Carr, who died Thursday at the age of 58, had a reputation for going after his own tribe with bracing honesty and clarity. With his unusual past as a crack addict, a distinctive scratchy voice, and quirky character, he had become a media figure in his own right as he chronicled journalism’s struggle to reinvent itself in the digital age. Carr shuttled to Boston once a week to teach journalism at Boston University, a routine he had started last fall. In one of the last interviews he gave before his death, Carr talked with Globe correspondent Stefanie Friedhoff in late January about his rookie teacher mistakes and the future of writing.

[Friedhoff’s questions are in bold italic. Carr’s answers are in regular type.]

What was it like, working with this next generation?

The first time they said, ‘Here comes the professor,’ I turned around looking for him, then realized, oh, that was me. I asked them to call me David. I did not feel a huge generational divide. I was not parenting or patronizing them. As long as they didn’t call me professor.

The first time they said, ‘Here comes the professor,’ I turned around looking for him, then realized, oh, that was me. I asked them to call me David. I did not feel a huge generational divide. I was not parenting or patronizing them. As long as they didn’t call me professor.

One generational difference is that they rely on texting, which is not a good business or academic application. I much prefer e-mail, which allows you to keep an archive, send attachments. I also made it clear that there was no texting or Facebooking during class. When someone did it, I would stop and say: ‘Do you need a few moments so you can finish what seems so important?’

The platform you used, Medium, allows for storytelling in all media. Did students experiment with different forms?

Some students included extensive video and audio, and some built stories around photographs, but writing played a distinctive role. Students were far more traditional than I thought they’d be, they were extremely animated by idea of longform narrative. I weighed heavily on blended content but they were not as interested as in big narratives.

Is there a future for writing, for the careful crafting of sentences and narratives, in the digital age?

Well, there are two problems with it. One, if you look at The New Yorker, GQ, and the Atavist or Longreads, there is a good supply of deep immersive writing, but there is an audience problem, in terms of what people are willing to commit to. And two, there is a business problem: getting paid enough to do what may pass for literary journalism.

Some signs are encouraging: Engagement levels, people staying until the end of the story, are quite high. But you have to earn the readers’ interest. Turns out that the phone, which was thought of as the enemy of longform — people read a lot on phones, they have become used to the infinite scroll. I read a lot on my phone, and I am old as dirt.

Did you like teaching?

Oh, this class was like a bomb going off in my life. I thought I could zoom up on an airplane on Monday, teach the class, do office hours, go to sleep, take the train back in the morning and be fine.

That is not how it went. There was a lot of steady communication with students. We produced a lot. Sixteen students wrote over 60 pieces, published in four collections on Medium. Four articles are on their way into the commercial market.

I enjoyed it all. The truth about teaching is, whatever you expect from them, you should be ready to give back. I’m glad I’m like a vampire. I still keep college hours and stay up late.

You have guest taught a lot. What surprised you about teaching a semester-long course?

I made a fair amount of rookie teacher mistakes. I brought in too many guest speakers.

I said ‘I love your personal essays, I will put comments in’ and then I had to really do that. It took me five seconds to say in class but 12 hours to finish.

I learned I talk too much. Every time I went quiet and solicited discussion, wonderful things were said and I thought, ‘Duh, of course.’ Part of the reason was that I wanted to look like a serious academic. I did not want to be one of these newspaper people who show up and tell stories.

There was also an important business lesson: My teaching assistant insisted I give students some class time to collaborate on their projects. I asked, ‘Why? They are doing this online all the time.’ But she was right — face-to-face time led to amazing cross-team collaboration and improvements. We think online communication works, but a well-run meeting has a lot of value.”

Are you a tough grader?

Not as tough as I thought I would be! When I was an editor, my office was known as Cape Fear. I did give out some rough grades to start with, but if kids demonstrated improvement, I gave them better grades. I was kind of torn about what to do when someone was a good writer but didn’t try very hard, versus someone who tried hard but wasn’t so gifted. It was very much a learning curve.

What did you tell students about their future in journalism?

I told them it’s a good time to be looking for a job. There is a lot of money in content in New York. You can’t be too picky about what you want to do initially. And you need to make your own judgments about where you want to [go] — regardless of where you went to school or who you know.

There is no doubt students will be walking into a news ecosystem that has more information, more sources, more providers, and more clutter. And they have to think about what value are they adding that will make them a signal above the noise and make their work stick out and have value — both in terms of who they work for and the kind of work they do. They have to [go] from creating commodities and toward creating things of value.”