John Cheever came up with an interesting premise for one of his greatest short stories.

In “The Swimmer,” Cheever’s protagonist, Neddy Merrill, lounges, hungover, poolside at a friend’s home on a Sunday afternoon.

It’s a muted gathering, suburbanites recovering from the night before, questioning the wisdom of drinking so much.

As he sits there, Neddy hatches a plan: he will swim home.

All of the homes in his neighborhood have pools, so he will follow a chain of them to home.

It’s an odd story that takes a surreal twist and ends in a gut-punch of sorrow and devastation.

If you haven’t read it, you should. It’s a brilliant piece of work.

Last week, I decided to follow Neddy’s lead, but with my own twist.

I never learned to swim and few homes in Massachusetts have pools anyway.

But I found myself in my former town for a doctor’s appointment.

When I was done, it was a brilliant summer day and I thought, “I’m going to do a Neddy.”

Instead of driving straight home, I decided I would go home via the libraries in each of the small towns that freckle the South Shore.

Every library has a Friends of the Library book sale. Maybe I’d find some books for sale — books for which I have no more room in my house (but that’s another story).

Here’s some of what I found.

. . . . . . . .

John O’Hara, The Big Laugh (Random House, $4.95)

Before you get all excited about that bargain price, I should point out that $4.95 was the list price when the book was published — in 1962.

I got this one at the Scituate Library, which has the best second-hand store of all the South Shore libraries.

I’ve read a lot of John O’Hara — a lot. Yet I’d never encountered this novel. How did I miss it on the “Books by John O’Hara” pages?

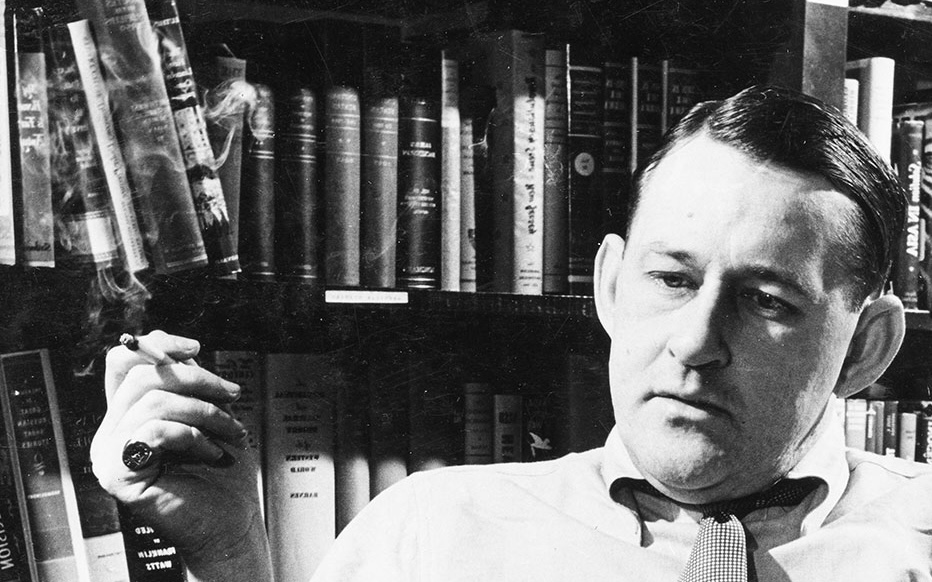

O’Hara seems to be largely forgotten today, which is a shame. He’s been credited with sort of inventing the New Yorker short story, and was an early and prolific contributor to that magazine.

His writing was tight. I’ve read some stories of his that were all dialogue, yet he managed to describe without describing.

He’s one of those writers I encourage students to read. There’s nothing flaccid in his work. Reading him [and James M Cain, Robert B Parker, Michael Connelly and others], I tell my class, is like giving your mind a suppository. You empty your brain of needless words, in the manner of a colon cleanse.

In addition to his terrific short stories, I’ve read his big novels — Ten North Frederick and From the Terrace — but The Big Laugh was a tremendous surprise. It told a stirring tale over the course of two decades and never did it drag. Turned out to be a quick read, unlike some of his other novels, which went on too long.

It’s the story of a shithead who goes from black sheep of his family to one of the reigning movie stars in the early days of talking films.

Don’t wait for a redemption arc, though the main character does prove himself to be more likable by tale’s end. There are some surprises along the way, and O’Hara keeps the story moving. He was a master at that.

Now to folks of the current generation, whatever your moniker may be: you did not invent sex.

Same goes for my generation. We Baby Boomers like to think that various carnal acts were unknown until our arrival and that we invented many non-Euclidean variations on the basic premise.

So here is a novel written by a man who was there in the 1920s and 1930s when the novel takes place. And the characters fuck like monkeys. There’s a lot of fucking here.

A lot.

I was a little surprised — not that people sportfucked so much back then but that the novel was so frank, being as it was published in 1962.

That’s either a note of caution or encouragement.

For me, I’m always happy to find a book by a favorite author that I have not read. The presence of so much fucking is like finding a bonus track on an album.

. . . . . . . .

Ben Mezerich, The Midnight Ride (Grand Central, $29)

This one caught my eye at the Norwell library.

I knew of Mezerich from his nonfiction books — The Accidental Billionaires and Bringing Down the House, two books I have not read.

But he’d always gotten good reviews and I was curious how he was as a novelist.

Turns out he is deeply entertaining.

This novel takes place in Boston, and those sorts of stories are always of interest to those of us who trudge through that insane city’s streets daily.

The book also focuses on a local mystery — the unsolved theft of priceless artwork from the Isabella Gardner museum decades ago. It brings together a plucky card-counter who makes her living at the gaming tables of the Encore casino, and an ex-con trying to start over.

These protagonists — Hailey Gordon the card counter and Nick Patterson the ex-convict — have an unusual meet-cute: it happens over a dead body in a hotel room.

The Gardner theft is only part of the story. The rest is steeped in Boston’s rich history and, as the title suggests, Paul Revere plays a part.

It has echoes of The DaVinci Code and National Treasure, but it’s a lot more fun.

Hailey and Nick returned in The Mistress and the Key, which came out last fall.

Looks like it’ll be back to the library-swim to find that one.

. . . . . . . .

Mario Puzo, The Fortunate Pilgrim (Random House, $25.23)

I read Puzo’s The Godfather not long after it was published and always considered it kind of trashy, because of one particular narrative thread.

Turns out Francis Ford Coppola felt the same way about that part of the book and it was a reason he initially balked on making a film of Puzo’s book.

We both were repulsed by the subplot that led to a character paying for his girlfriend’s surgery. He had this young woman go under the knife so she would be tightened up — in the non-Archie Bell & the Drells meaning — giving, presumably, greater sexual pleasure to both of them.

As I learned more about Puzo’s back story, I’d heard of his first two novels, The Dark Arena and The Fortunate Pilgrim. Both were tagged as “literary fiction” and both were failures.

So he wrote The Godfather strictly to make money. It was a paycheck book, so the trashier the better.

(In the years since, I’ve relaxed more and found The Godfather to be a generally entertaining book and I skip over the surgery scenes.)

I happened across The Fortunate Pilgrim at the library in Hanover and grabbed it immediately.

I’m not sure I’d say this was literary fiction, but it was a compelling story of New York’s Italian population in the 1920s and 1930s. Putting this story next to Puzo’s own, we can see the elements of autobiography.

The primary character is Lucia Santa, an emigre from the farms of Italy, who comes to the New World and is deposited into poverty in Manhattan.

She marries, has children, and is left to raise a family herself on the mean streets. It’s a tough, often tragic, life.

Puzo made no secret of the fact that Lucia is based on his mother and that the protagonist of his most famous novel, Vito Corleone, is also based on his mother.

It’s a good and enthralling novel that shows how much American lives have changed in the last century. The violence and the spectre of death look over the shoulder of us all.

This is an entertaining story and becomes a tribute to the immigrants who built America.

But it also has some irritating touches. Puzo has a group of elderly Italian women who sit on the tenement stoop and form sort of a Greek chorus. Puzo calls them crones. One use of “crone” is probably okay. He uses it six or seven times over the course of a couple pages early in the book.

Consider this your crone warning.

. . . . . . . .

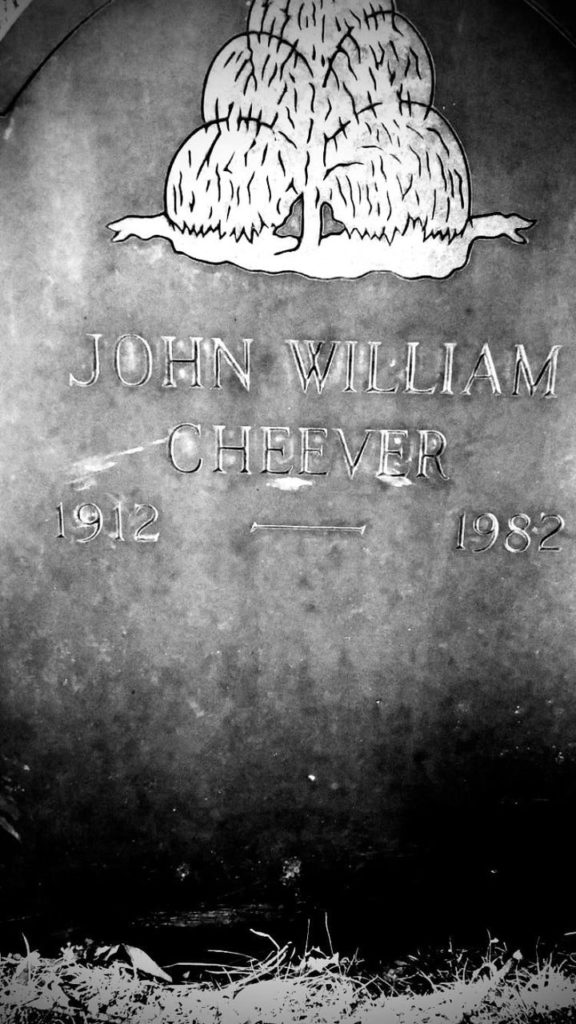

I couldn’t go by the Norwell library without stopping at John Cheever’s grave.

A few years ago, I discovered that his body rests just a few miles from my house, and across the street from The Tinker’s Son, a Irish pub where my youngest son has worked for the last four years.

Odd, to find one of your literary heroes buried just six feet away from a parking lot serving a convenience store.

Fortunately, Cheever was honored by a local denizen of business who built The Cheever Tavern adjacent to his grave.

I have the feeling he would approve of the place named in his honor. The food and the booze are excellent.

If you’re nearby, visit the place and seek out his grave. Then you can say you were truly (an) over a Cheever.

Back to the swim.

I recently picked up a few more books during my swims– State of Wonder by Ann Patchett and a Pete Townshend novel. I have a lot of good reading ahead.

Come on in; the water is fine.