May God Bless

and Keep You Always

From The Gainesville Sun, May 24, 2001

Dylan is in his eighties now. I wrote this for my then-local newspaper on the occasion of his 60th birthday, just before leaving on my Highway 61 trip, which was partly inspired by his music.

……….

Maybe Bob Dylan likes to keep secrets. Maybe he just likes to be mysterious. Maybe he thinks his songs should speak for themselves.

Whatever the reason, His Bobness doesn’t talk about his songs very much. But he did say this about “Forever Young,” his 1973 composition: “I wrote it thinkin’ about one of my boys and not wantin’ to be too sentimental.”

“Forever Young” is every parent’s prayer, a wonderful song that transcends greeting-card wisdom because of Dylan’s magnificently ravaged voice.

Leave it to Dylan, in one of his rare public comments on a song, to belittle it. It’s as if Leonardo said of Mona, “Oh yeah, that thing . . . . Just some sketch I did once.”

May God bless and keep you always

May your wishes all come true

Was it about “one of his boys” or was it about himself? Seems Dylan’s still young. He’s always on the road, playing rock’n’roll with the fervor of an artist half his age. But in case you’ve missed the media blitz of the last week, here’s some news for you: Bob Dylan turns 60 today.

(Pause for a case of mass Baby Boomer shock.)

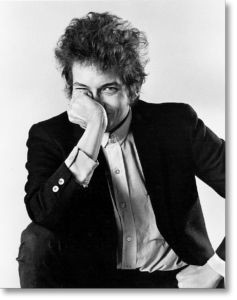

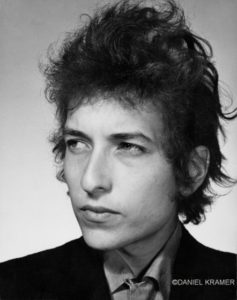

Yes, this is that big-haired, polka-dotted, drawn-out-voweled boy who shook up the popular culture of the 1960s with his challenging songs, his abraisiveness, his mocking of popular-music conventions. Yes, that Bob Dylan turns 60 today. He’s had a Modern Maturity subscription for five years now. He’s a grandfather several times over. No one in his band was born when he released his first album. Hell, none of them were born when he released his 10th album.

May you build a ladder to the stars

And climb on every rung

And may you stay forever young

He came out of Hibbing, Minn., as Bob Zimmerman, but transformed himself into Bob Dylan somewhere on the way to dropping out of college his freshman year. He took his new name from television western star Matt Dillon of “Gunsmoke,” but didn’t mind it when people thought it was after the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, so he spelled it Dylan. He sang in coffee houses, performing folk songs and Woody Guthrie songs and spinning yarns about his life on the road as an orphan hobo – all lies if we’re talking about Bob Zimmerman. But as Bob Dylan, he could be whatever he wanted. As he once said, “I’m only Bob Dylan when I want to be.”

And so he went to New York in 1961, met Woody Guthrie – then dying of a degenerative disease – and, apparently in a matter of seconds, got himself a recording contract. He was nearly dropped from Columbia Records when his debut album stiffed, but then his muse showed up. The songs wouldn’t stop: “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” “The Times They are A-Changin’” and the song for his muse, “Mr. Tambourine Man.” He took prolific and squeezed it until it screamed for mercy. He once said of a composition, “Man, I didn’t write that song; I vomited it.” However he expectorated them, his songs were overwhelming. When all of the big-time rock’n’roll songwriters of the 1960s first heard Dylan (we’re talking Lennon-McCartney, Jagger-Richards, Brian Wilson, etc.), the reaction was always the same: this guy scares me; he’s going to transform popular music. They were right.

May you grow up to be righteous

May you grow up to be true

He was the darling of the folk crowd in the early 1960s, with his finger-pointin’ songs about racial injustice and the depravity of war. He sang at the March on Washington, as preface to the “I Have a Dream” speech. He also sang in the front yards of sharecroppers. He was the keeper of the flame for good old-fashioned activism.

Or so it seemed. The arrival of the Beatles in 1964 annoyed Dylan. Here was a bunch of British guys who’d cut their teeth on American rock’n’roll and now, it seemed, the Brits had taken over the airwaves. American rock’n’roll was dead and no one wanted to fight the British Invasion. It was time to plug in.

And so Dylan went electric in 1965, with a series of three masterful albums – Bringing it All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde and Blonde (in 1966) – that took rock’n’roll from moon-and-June rhymes to something much more complex. Part of the 1965 assault was his six-minute rant called “Like a Rolling Stone.” It’s apparently aimed at a child of privilege forced to learn the lesson of being judged on her merits, not those of her parents. Or is it? Dylan doesn’t talk much about his songs, but he said a few years ago of this song, “Did anyone ever consider that maybe it’s an interior monologue?”

Kind of puts it in a whole new perspective.

A motorcycle accident in 1966 got Dylan off the rock’n’roll / concert tour / drugs treadmill that had already given him a death sentence. He got a reprieve – a family life (a wife, two girls, three boys) and a bucolic existence in country-estate exile for the end of the 1960s. He fully re-emerged in the mid-1970s, with concert tours and albums that matched his earlier work. His conversion to Christianity at the end of 1970s shocked millions of his fans and drove them away, many never to return. Yet Dylan’s music was always full of Biblical references; in many ways, the conversion was the next logical step.

May your hands always be busy

May your feet always be swift

He’s been many Bobs over the years – young Protest Bob, angry Rock’n’Roll Bob, Country Bob at peace with his family, Gypsy Bob in the mid-1970s, Gospel Bob . . . and, in the last decade, he’s been just Good Old Bob. No one writes better songs about the complex majesty of aging. No one is a more fearless detective of the heart. And no one in popular music sings with a greater depth of feeling. When he was young, he used to strain to sound like an old man. It comes easier these days, and it sounds wonderful.

When I was in high school, my father used to come into my room when I was playing a Bob Dylan record. “That guy can’t sing,” he said. I had my answer ready: “You’re right, Dad. He can’t sing, but he’s a great singer.”

May you always do for others

And let others do for you

I’ve seen him many times over the years. I often go, expecting to be disappointed. I never have been. I’ve taken friends, my kids and other people, mostly younger. They sit through the first few songs without reaction before it hits them. Once, a concert companion grabbed my sleeve and said, “My God! I’m in the same room with Bob Dylan!” It’s kind of like waking up and finding Mount Rushmore in your back yard.

Bob Dylan is the sweeping American musical experience wrapped up in one fairly short, curly-haired dude. He knows his contribution to our culture, even if we don’t (yet). Like Walt Whitman, he’s a pure product of America. There have been a lot of “new Bob Dylans” over

the years – John Prine, Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello. Thankfully, most of them had the talent to be themselves. Dylan’s 40-year career and his 42 albums make it clear he didn’t need to be replaced. He’s made his bad albums, but he’s also made good albums, great albums and masterworks that belong in every American home.

I’ll honor Bob Dylan’s birthday today with friends by having my annual Bob Dylan birthday lunch at a Bob-worthy diner. And then I’ll pack for a road trip with my 19-year-old son. We’re traveling from Thunder Bay, Ontario, to New Orleans on Highway 61. That’s Bob’s highway, running from Main Street of his hometown in Minnesota through the places that gave him the music that inspired him on his high-school bedroom radio: St. Louis, Memphis, the Mississippi Delta and New Orleans itself. This is for a book I’m writing steeped in Dylan, the blues, the country’s racial divide and the changing nature of the American family – all in all, a very Boblike experience.

Tonight, Bob Dylan takes a rare night off. He said he truly learned the joy of performing from Jerry Garcia in the 1980s, when he toured with The Grateful Dead. Since then, he’s been on the road over a hundred nights a year, tearing down the house with his blistering rock’n’roll, moving audiences to tears with his country-blues laments. It’s as if he’s taken a page from that other Dylan (Thomas). He will not go gentle into that good night. From a hundred stages every year, he rages against the dying of the light.

May your heart always be joyful

May your song always be sung

And may you stay forever young

So maybe he was talkin’ about his boys in that song. Maybe it’s a song for himself, his prayer as a man and an artist. But I’ve got to wonder – maybe he was talking about us. Maybe that song was for his audience. You can’t ever be sure with Bob Dylan. I wrote a book about the guy, but I don’t want to suggest that I know. I just wrote this thinkin’ about Bob and not wantin’ to be too sentimental.