Cozumel, 1974

Afterword from The Cozumel Diary by Al Satterwhite (Redcat Editions, 2013)

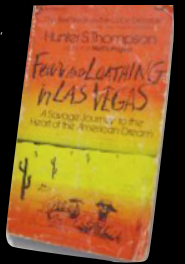

The spine broke almost immediately and soon the cover needed cellophane tape to stay on. The book was pockmarked with punctures, as if someone stabbed it with an ice pick. And before it fell into my possession, someone bit it. The human teeth marks were imprinted all the way up through page sixty-five.

It’s a forty-year-old paperback edition of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The pages nearly disintegrate on touch, so I wouldn’t dream of trying to read this copy again.

But I keep it as a relic of that time when Hunter S. Thompson was king.

I’m not sure who actually bought that book, but it was passed around my newspaper’s newsroom like holy writ. All the reporters read it, usually taking it home and inhaling the book in one sustained gulp. The next day, they showed up in the newsroom starry eyed and laughing. Suddenly, everything was intense. Hunter wrote with such power and ferocity that it was hard to not see the world with his eyes – the “right kind of eyes,” as he put it. He changed the way we looked at the world and how we looked at what we did for a living.

The book was passed on to another reporter and then another one, and then finally to me. I never let it go.

To those of us who were journalists in the early seventies, Hunter S. Thompson was a god. He was Picasso and we were punks with Crayolas. We saw his writing – and the writing of Tom Wolfe and a few others – as vindication of our trade. They showed us the possibilities of journalism, and made us realize that journalism wasn’t just the means to an end, but was a legitimate end. Thompson, Wolfe, Joan Didion and the others made it clear that nonfiction – oh let’s just go ahead and say it: journalism – could become literature.

Reading Hunter Thompson was exhilarating. The problem was, it made all of us want to write like him. Being young and stupid, I tried. I soon realized there was only one guy who could write like that.

Flash forward. I’ve been teaching writing for decades now, and Hunter Thompson still has the effect on my students as he had on that earlier version of me.

Every semester, at least one or two students will tell me they want to do something different for their final piece in the course. “I want to do something gonzo,” they say, “you know, like Hunter Thompson.”

“Sure, go ahead,” I tell them.

When they fail miserably, I tell them, “See: only one guy can write like that, and now he is dead. But only one person can write like you.”

Corny as it sounds, that helps young writers grope toward finding an individual style. That revelation helped me.

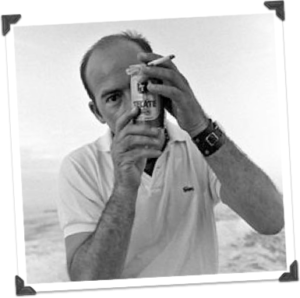

Look at Al Satterwhite’s pictures of Hunter in Cozumel in 1974: He’s mid-thirties, athletic, whip-smart, funny as hell, and at the absolute top of his game. Look in those eyes and you see the confidence of a man who knows what the fuck he is doing.

He was coming off Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and his celebrated reporting of the 1972 presidential campaign for Rolling Stone. He might’ve been the most famous writer in the world when he met up with Al in Cozumel in 1974. He was certainly one of the most admired.

I can’t speak for everybody who fell under the spell of his writing then, but I can tell you that reading Hunter Thompson was vital to my generation and to those who worked for newspapers and magazines. Being young, we took his self portrait at face value. He was always a character in his stories, usually portraying himself as a manic mad dog about to explode with revulsion over some atrocity in Nixon-era America. He wrote frankly about his drug use, his boozing, and his crazed encounters with everyday geeks.

It wasn’t until I met him that I realized he had given us a somewhat exaggerated version of himself. Sure, he did those things. But he was also a polite, courteous friendly Southern gentleman. The “Hunter Figure”would emerge when he walked onstage to do a talk or when he was recognized by acolytes.

People ask for a definition of Gonzo Journalism. The safest one is that it’s whatever Hunter wrote. But it can also be defined this way: it’s a story about Hunter Thompson trying to write a story. This required him to turn himself into a character and the Hunter Figure was, in the estimation of historian Douglas Brinkley, one of the great literary creations of the 20th Century.

The problem was that too many people believed that the character — soon to become the caricature — was the man. A mythology grew that he was a wild beast who could barely walk upright. I remember a college friend saying, only half facetiously, “Hunter probably like takes a hundred hits of acid, then sits down to write, man.”

Obviously, not. Someone who wrote with such skill, with such a gift for craftsmanship, made it look easy by working awfully hard to make it look so easy.

But the caricature grew and soon gave way to Uncle Duke, the comic-strip character in “Doonesbury,” and that became the popular perception of Hunter S. Thompson. The fame — or infamy, as he thought of it — was too much. His celebrity crippled him so much that he could no longer work as a reporter. He was more famous than some of the people he covered.

He could still write, of course, but there was a continental divide in his career when he stopped being a reporter and became a reactor, a commentator — sort of an H.L. Mencken for the new millennium.

The writing was still good. Though he was semi-silent for the late seventies and the early eighties, he was not, as was the conventional wisdom, burned out on drugs. He was ending a marriage and enjoying life with a new girlfriend. His brain wasn’t pickled. He wasn’t writing because whatever money he earned would be split in half with the divorce settlement. So he just lived.

Eventually, he began writing again — first for the San Francisco Examiner, later for ESPN — and then the books started coming. By the time of his death, we might even say he’d become prolific. Critics accused him of trafficking in self parody and there is some of that in his later work. He described himself as a lazy hillbilly, so maybe it was fiscally wise to keep that image out there, sell books to his rabid fans, and sleepwalk through a magazine piece now and then.

But he never lost it. When he wanted to, he could still produce masterful writing. When Richard Nixon died, even enemies stepped forward to offer a few polite words of praise. But Hunter wrote a brutal and brilliant obituary called “He Was a Crook.” In many ways, Nixon was Hunter’s muse and often inspired his best work. When the terrorists attacked on September 11, 2001, Hunter produced a piece on deadline that not only reported on the horrors of that day but predicted the endless war to follow.

He also thoroughly revised his 30-year-old novel, The Rum Diary; oversaw publication of his hilarious and insightful correspondence; and saw himself portrayed onscreen by gifted actors Bill Murray and Johnny Depp.

And then he killed himself, on February 20, 2005. Perhaps it was because of failing health. Maybe he thought he’d written himself into a corner and couldn’t escape the prison of his persona. Perhaps, as actor George Sanders said when he took himself out, he was “bored.”

Whatever the case, we’re still sorting through his life and legacy. I wrote a short semi-scholarly book on him a long time ago: Hunter S. Thompson (Twayne, 1991). He liked it. I know this, because he addressed me as a “shit-eating freak” in his thank-you letter. My purpose was to take the focus off of his public image and focus on the gifts of his writing. After his death, I produced a full-life biography called Outlaw Journalist (Norton, 2008), and again kept my focus on this fine American writer and not on the clownish caricature the public had bestowed on him.

He was a complex and confusing man. There is that seam in his life, when the fame and infamy overtook him, when he was no longer able to be a reporter and had to deal with being too famous to do the job he did best. He became an observer of events from afar. Thank God for satellite television.

So look at these pictures of Hunter S. Thompson in Cozumel. Craig Vetter did much more than interview his subject. Al Satterwhite didn’t just take some great photographs. They both captured the strange and savage Hunter S. Thompson at his peak.

I’ll drink to that.