Good Stories Well Told

Appeared in the Tampa Bay Times, March 2006

When the talk turns to “the future of journalism,” most of the free world falls asleep. But those with stamina to discuss the subject start squawking about new technologies, radical delivery systems and wondrous ways of beaming information directly into the cortex of the American consumer

But who cares about the delivery system? The future of journalism is really in the past – in great storytelling. From the time our hairy ancestors painted on cave walls, that’s all we’ve ever wanted: stories – good stories, like the stories we heard while curled up in daddy’s lap.

Once upon a time, not too long ago, a bunch of journalists threw off some of the conventions that came with journalism’s middle age as a “profession.” As journalism became more respectable it got more boring. It was time to bring back some fun. It was time to tell some good stories.

Enter Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Hunter Thompson, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer and scores of others. Author Marc Weingarten calls them The Gang that Wouldn’t Write Straight, but at the time (the 1960s) they were called the New Journalists. As Wolfe was quick to point out, though, there was nothing “new” about them. They were telling stories in the manner of their forebears – Charles Dickens, Emile Zola, Samuel Johnson – all of whom did time as journalists.

The New Yorker began experimenting with long-form creative non-fiction back in the 1940s and John Hersey’s Hiroshima, a novel-like telling of what happened in the days after the bomb was dropped, is pretty good DNA for the literary journalism that followed.

But Gay Talese kicked things up a notch when he started writing his profiles for Esquire magazine in the early 1960s – profiles of celebrities such as Joe Louis, Frank Sinatra and director Josh Logan that read less like the usual dig-me-with-the-big-star tell-alls than short stories that delved into character and motivation.

Talese, a New York Times reporter , became the inspiration for Tom Wolfe. At that point Wolfe was a talented reporter on a talented news room staff (The New York Herald-Tribune) but not yet the man in the ice-cream suit with the zip-zam-zowie-and-swoosh prose. He picked up a copy of Esquire one lunch break in 1962 and was eight paragraphs into Talese’s profile of Joe Louis when he tossed the magazine down and said, “What-inna-name-a-Christ-is-this?” Talese’s use of fictional techniques to tell a true story made Wolfe want to play that game.

Wolfe talked the editors at Esquire into letting him cover a custom-car rally, something he thought suitable for a storytelling adventure. But after a trip to California to see this new subculture up-close-and-personal, Wolfe returned to New York to a massive case of writer’s block. Finally, over deadline, the Esquire editor called and said that since Wolfe had failed to write his assigned story he needed to type up his notes and send them over to the magazine office, where some nameless drudge on the staff would turn them into an article. Wolfe sat down to write a memo after work that night. When he got up from his desk, the memo was 49 pages. He delivered it to Esquire the next morning and that afternoon, the magazine’s editor called to say the “memo” would run verbatim in the next issue. Thus Tom Wolfe found his style.

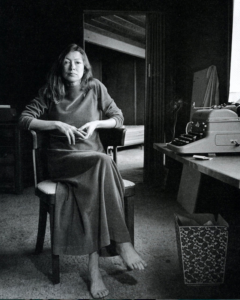

And from the time Wolfe turned his eye to American popular culture in the 1960s, there was no going back. Novelists Truman Capote and Norman Mailer set aside fiction to write about the violence of the 1960s and Joan Didion dissected that decade and performed a psychological autopsy on many of the participants.

These were great stories. Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, though non-fiction, stands as the great American “novel” of its time. Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood got inside the minds of murderers and their victims. Norman Mailer got inside his own mind and turned himself into a historical character in The Armies of the Night. Then Joan Didion turned the truth of the decade into near-poetry in Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

All of these books first saw light in newspapers and magazines willing to give the writers license – and room – to tell stories.

The story of these storytellers makes for compelling reading. Weingarten returns to familiar territory – how this new journalism came to be. Tom Wolfe already told the story in his anthology, The New Journalism. But Weingarten conducts new interviews and tells more behind-the-scenes stories, including the tale of the all-out war between the New Yorker and Tom Wolfe that broke out when Wolfe wrote a story about the semi-cloistered nature of the magazine’s editor, William Shawn. Even J. D. Salinger came out of hiding to heap insults on Wolfe.

Wolfe, Capote and the gang are the stars of the story, but the supporting players – the magazine editors who helped shape the non-fiction revolution – play a significant role.

Harold Hayes, Esquire’s editor in the 1960s, produced the magazine that provides the greatest cultural chronicle of that time. He rose through Esquire’s ranks in the 1950s, outdueling colleagues Ralph Ginzburg and Clay Felker for the top job. Felker went off to the New York Herald Tribune, where he turned the Sunday magazine into a lively showcase for Tom Wolfe. (That magazine, New York, is still with us, outliving the Herald-Tribune by nearly 40 years.) Hayes and Felker both pushed Wolfe, Talese and the others in new directions and gave them all the editorial space they needed. Editors like Hayes and Felker are rare.

The maverick among these mavericks comes along in the third act of Weingarten’s story. Hunter Thompson took a few bites out of New York early in his career, but left the world’s media center just as the New Journalists began percolating on the streets. Off on his own path through South America, the Caribbean, Big Sur and Colorado, Thompson made his name at the end of the 1960s as a participatory journalist – he wanted to write about the Hell’s Angels so he rode with them and eventually got stomped by them. His subset of New Journalism – gonzo journalism – always put himself and his agony of getting the story on center stage. It’s a technique often imitated, but Thompson was the only one who could pull it off. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels, good as it was, became merely a warmup act for his greatest work, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Those same wags who scratch their skulls and ponder “the future of journalism” also mourn the old days of the 1960s, when journalism seemed to matter more than it does today. Maybe that’s because they spend too much time thinking about technology and demographics and costs-per-thousand. Maybe those media gods need to think a little more about storytelling. If they worry about the public turning away from newspapers and magazines, maybe they should give readers what they want: good stories. The next Tom Wolfe or Joan Didion might be out there somewhere. Give them a little time and some space to tell their stories and maybe we’ll have another flowering of great journalism.