Life on the Death Beat

Appeared in The Satellite magazine

I started writing for daily newspapers in 1969, and in those prehistoric days we wrote on manual typewriters and heard the lovely music of iron-clad keys pounding soft, pulpy copy paper.

Today, newsrooms glow with the surreal windows of computer screens and paper isn’t involved until the final step of printing.

The gods of journalism, in their wisdom, began eliminating some key steps in the process from writer’s brain to reader’s eye.

In this ancient time of which I speak, copy was typed by a reporter, edited by an editor, typeset by a typesetter and proofread by a proofreader, all before it got onto the page that would go out into the world.

These days, reporters write their stories onscreen, the editors edit onscreen and typesetters and proofreaders have gone the way of the dodo.

I tell you this because that was the reality of journalism just a few decades ago.

Another reality was that beginners, newsroom proles such as myself, were given the offal (in the sense of butcher’s offal) work no one else wanted: covering the Saturday-morning “meet-the-mayor” sessions in city hall, doing numbskull local-reaction stories and, of course, writing obituaries.

Obituaries were the foot in the door for those wanting to pursue the peculiar craft of journalism. Even the great Edna Buchanan, the Miami Herald’s Pulitzer-winning police reporter, got her start writing obits.

These two elements – the old technology and the pay-your-dues stepping stone (now bypassed by many young reporters, thanks to the 1970s-and-beyond boom of university journalism schools) explain my peculiar fondness for obituaries.

That was my first job on my first newspaper and I took great pride in the work. I learned much by my daily calls to all funeral homes in the region. “Nothin’ today, little buddy,” one funeral director would say when I’d call and identify myself. He seemed happy that no one died, even though that was bad for business.

That was my first job on my first newspaper and I took great pride in the work. I learned much by my daily calls to all funeral homes in the region. “Nothin’ today, little buddy,” one funeral director would say when I’d call and identify myself. He seemed happy that no one died, even though that was bad for business.

Funeral directors generally answered the phone with a grim voice but sometimes became loquacious when they discovered I was only a reporter.

How well I remember the peculiar names of some of my first subjects: Archer W. Fishback and Bushrod Yockey. I kept a file of my favorites.

And it was a moment of sadness for me when I wrote the obituary for 96-year-old Mrs. Charles Schiller. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I need to know her first name,” I heard the funeral director shuffling papers on the other end of the line. “I’m sorry, little buddy – don’t seem to have that information.” Short laugh.

My God, I thought. This woman’s identity has been lost. All she is, after 96 years of life on this planet, is an appendage of someone else.

My God, I thought. This woman’s identity has been lost. All she is, after 96 years of life on this planet, is an appendage of someone else.

But the most telling experience during this short apprenticeship to a glorious reporting career was an error. One of the key elements of every obituary is the listing of survivors. I have never written a sadder sentence than “There are no survivors.”

Sometimes, I thought of going to these funerals because we all need to be grieved. But what was worse was the time when my masterpiece of simplicity “He is survived by his sons” appeared in the newspaper as “He is survived by his sins.” That was probably true, but it was not my intent to be philosophical. I merely wanted to list the names and residences of his sons. I went into the backshop, looked on the spike by the proofreader’s desk and saw that I had gotten it right (sons), but that the typesetter had mis-typed it (sins) and that the proofreader had missed it.

The error was not mine, but that didn’t matter. It was an error – and it must have left the survivors – sons and daughters – mortified.

Used to be, we could be assured of our name making the paper three times – when we were born, when we were married and when we died. The marriage one, of course, is not always a gimme and some papers ,have started charging for wedding announcements. Maybe newspapers will soon start charging for death notices, but the concerns about collecting payment from the dead might be a problem.

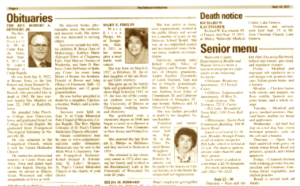

When I hear on television that a great statesman, a celebrated writer or even a television celebrity has died, I’m not really sure they are dead until I read the full, flowering obituary in the New York Times. When I was that young apprentice four decades back, I was stunned to learn that the Times had an obituary staff and that obituary reporters interviewed people about their lives and kept their obituaries on file.

I learned the value of this a few years after I left the obituary beat when former President Harry S. Truman died – right on deadline – and we were able to publish four full pages about his life and presidency. The Associated Press also had obituaries ready to go.

Those New York Times obituaries are often magnificent, even better than those Academy-Award filmclip tributes to fallen film idols.

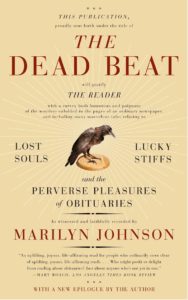

In her wonderful new book, The Dead Beat, Marilyn Johnson explores the fascinating world of obituaries and the people who write them. This isn’t just a book for newspaper people or death junkies. It’s a book at turns comic and respectful about how we report this inevitable fact of life. We can avoid employment, matrimony and responsibility – but we cannot avoid death and so it is always among us, the 600-pound gorilla and most of us don’t talk about it.

Johnson takes us into Obitworld and finds that the people who write obits for the big-time newspapers as well as the obscure publications in the hinterland have developed whole new subsets of language to describe what they do. In fact, since death is a growing business, the good newspapers put more people and money into reporting it.

Some writers have emerged as obituary superstars and obituary writers have begun to gather annually at conventions. There’s almost a competition to out-do each other with outlandish obituaries that dryly compact usual resumes into stentorian sentences that convey much behind the suppressed great-grey smirk.

An example:

Jeannette Schmid, the professional whistler who has died in Vienna aged 80, performed with Frank Sinatra, Edith Piaf and Marlene Dietrich; she had been born a man and had fought in Hitler’s Wehrmacht before undergoing a sex change in a Cairo clinic.

Now that, Johnson chortles, is a masterpiece. Top that, New York Times. (It appeared in London’s Daily Telegraph.) A professional whistler is odd enough, but the other elements of the career, followed by the sex change, are remarkable. The at-a-Cairo-clinic line merely underlines the virtuosity of the obituary writer’s craft.

There’s even such a thing as a “death beeper,” used by obit writers who subscribe to a service that lets them know when celebrities pass on to the green room in the sky. It’s a little heads-up to let them know that it’s time to get to the office and update the obit on file for Ernest Borgnine, Tony Bennett (what a sad day that will be) or the last surviving cast member of “Gilligan’s Island.”

Of course, the changes in technology since the days of typesetters and proofreaders have allowed legends to grow in the obituary field. Obit writers check the competition online and growl when a fellow death writer comes up with a better line or better turn of phrase. The rise of celebrity culture seems to demote the rest of us to mere agate type – the tiny death notices found in the bowels of a newspaper – but a great obituary writer longs to find the ordinary live extraordinarily lived.

Of course, the changes in technology since the days of typesetters and proofreaders have allowed legends to grow in the obituary field. Obit writers check the competition online and growl when a fellow death writer comes up with a better line or better turn of phrase. The rise of celebrity culture seems to demote the rest of us to mere agate type – the tiny death notices found in the bowels of a newspaper – but a great obituary writer longs to find the ordinary live extraordinarily lived.

Celebrities are easy. Turning a neighbor or a local shopkeeper into an interesting obituary isn’t so hard, these writers claim. It’s simply good storytelling and, after all, that’s what journalism is supposed to be. What gives these writers pride is their part in underlining a basic moral principle – that all life has value.

The Dead Beat is often hilarious but Johnson walks a delicate line that never fails to give these lives discussed the reverence they so richly deserve.