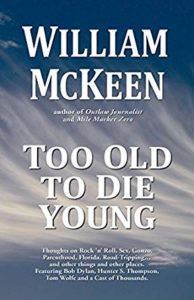

Too Old to Die Young

From Too Old to Die Young (Dredger’s Lane Press, 2015)

I hope I die before I get old.

PETE TOWNSHEND

Well, Pete – old buddy old pal – you didn’t make it. You’re over 60, but you were barely 20 when you wrote that famous line in “My Generation.” And, dude, I’m not saying 60 is old. Not at all. Time is relative, as Dr. Einstein would say, and the older I get, the younger 60 (or 70 … or 80) seems to me. It’s all a state of mind, right?

But back then, maybe 60 seemed old. With the invincible fury of youth, anyone over 30 was ancient. But from where we sit today, 30 is a whippersnapper and 40 is a punk.

As those of us in the baby boom generation lurch toward our assumed retirement, it’s interesting to ponder that those icons of our youth … our rock ‘n’ roll stars … are getting there just before us, maybe (once again) giving voice to our feelings, as they did back in the 1960s.

Popular music is an industry built on youth – which is to say on sand – and so when a rock ‘n’ roll artist reaches a milestone, we all feel it, because we’ve marked our time by their lives.

Maybe we first fell in love to Rubber Soul, and so when George Harrison died, it was a personal loss. An old girlfriend I hadn’t spoken to in 10 years called me that day, to talk about George. He was the quiet one, the most reserved of the Beatles, and he sang the standoffish and self-protective “If I Needed Someone” on Rubber Soul. (I had courted that girl with Beatle music.) Love was so simple for John Lennon and Paul McCartney. It was more complex for George, who seemed to understand us.

Maybe we felt our first rush of independence – and all the joy and fear that it meant – when we heard the confusion and anger in Bob Dylan’s rant, “Like a Rolling Stone.” He might have just been telling us to grow up (as our parents always did), but he said we must do it on our own terms and we must do it now.

And maybe, after our hearts were broken the first few times, we began to feel the premature resignation and weariness of Joni Mitchell in “The Circle Game,” looking back on her fractured life from the vantage of an ancient 24-year-old. The seasons, they go round and round.

Music is a great and mysterious motive force in human life, so it’s no surprise that musicians have come to represent more than mere entertainment to those of us in the pampered and largely affluent postwar generation. Maybe we’re selfish, thinking this is just a baby boom thing and that earlier generations didn’t invest so much of themselves in their artists. To us, Bob Dylan, John Lennon and Joni Mitchell were people who spoke for us when we couldn’t form the words. Unlike the musical icons of before – Rudy Vallee, Bing Crosby, even Elvis Presley – the Dylan/Lennon/Mitchell generation sang songs that they wrote. It was all very personal.

And so now, those of us who fall into the two-decade-wide window of baby boomer, are beginning to turn 60 this year. Those who provided the soundtrack of our youth are – mostly – no longer in the arena. Some are dead, some are retired, some are shunned by the marketplace that celebrates youth – the youth they used to have, the youth their lives and music used to embody.

A few are still on the road, heading for another joint, playing new music or flogging their oldies.

These are the artists who made the music of our odd generation – in many ways we are selfless and altruistic, in other ways narcissistic and coddled. How will we handle aging? I suspect it won’t be pretty. Vanity, thy name is boomer.

No, we never met Pete Townshend, but after 40 years of listening to him, he seems like an old buddy. The records he made with the Who are the soundtrack of any teenager’s frustration: “I Can’t Explain,” “My Generation,” “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

Bob Dylan, then and now, is a cipher, yet after four decades, we comfort ourselves with the illusion that when he croaks his ballads of mortality, he is speaking just to us.

Joni Mitchell has content herself to stand on the side of the stage, making cogent and illuminating observations about the ridiculous parade of life, and in our darker moments, we think she has been reading our e-mail.

It’s hard to age gracefully in a culture of youth. It’s hard enough just to live. Even rock stars have a tough time of it. Townshend is a rock icon, but he’s also a sexually confused recovering substance abuser who may or may not have issues with child pornography. (Life ain’t pretty.) Chuck Berry, a founding father of rock ‘n’ roll, has been busted spending some of his rocking-chair years watching surreptitious videos of women in the restroom of his nightclub. James Brown, the hardest working man in show business, schooled such pupils as Mick Jagger and Michael Jackson in the art of entertainment, yet seems to have issues with firearms and speed limits.

Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys is one of rock’s greatest eccentrics, and for a long period a near-Greta Garbo-like recluse. One of his collaborators once said of him, “He is a genius musician but an amateur human being.”

That seems to describe a lot of these people.

Every day, I stand in my den and look at the photograph framed over the couch. It’s a signed, limited-edition print of an Elliot Landy picture instantly recognized by anyone of my generation – five young men standing on a hillside. It’s sepia-toned, adding to the feeling that we are looking at some relic of the old, weird America.

There’s a 19th century feel to it, even though this picture of The Band was taken in early summer 1968, on a hill near Woodstock, N.Y. It appeared on the cover of Music From Big Pink, the 1968 album that changed the direction of rock ‘n’ roll music, taking it from the precipice of studio weirdness and hippy-dippy pretension back to the basics of three chords and the truth. The five members of the Band stood on that hillside, dressed – so one wag said – like frontier rabbis, giving us a calm, reasonable and reassuring voice in times of insanity.

Where are these boys of summer now? Rick Danko died of a heart attack in his sleep; Levon Helm battled throat cancer; Richard Manuel committed suicide in a Florida motel room; Garth Hudson retired from performing, but still works as a session musician; and Robbie Robertson retired from performing to create a film score now and then.

On that hillside, their lives held so much promise. They’d paid their dues as a bar band but they were poised for greatness. They exuded confidence and potential. Their eyes were fearless.

America is a culture that sanctifies youth and we cannot stop that culture from devouring those who have served their purpose. We try to hold on to youth with medicine and suture and plastic surgery. If our icons can’t hold back aging, what makes us think we can?

Their emergence marked a return to the simplicity of basic American music, an embrace of tradition after the madness of psychedelia. Although four or the five members were Canadian, they understood America better than most of us. Few artists, other than the Grateful Dead, could embody that communal ideal of music, peace and love as well as the Band. And now, Levon Helm and Robbie Robertson won’t even speak to each other.

Couldn’t we keep them under glass, as an artifact of that more hopeful, innocent time when we were young? If we could do that, would we still be young?

Afraid not. America is a culture that sanctifies youth and we cannot stop that culture from devouring those who have served their purpose, to make way for the Newer and Younger. Newer isn’t necessarily better – in most cases, far from it. We try to hold on to youth with medicine and suture and with so much plastic surgery, some of our favorite performers look like perennially delirious reptiles. If our icons can’t hold back aging, what makes us think we can? Can’t we just celebrate what we are?

Sure, perhaps it’s hard to see Paul Rodgers, a man older than me, strutting around the stage in leather pants, belting out “All Right Now.” But if I had his talent and ability, wouldn’t I want to do that? Aging gracefully might be possible – with regular workout, a healthy diet and the right sort of leather pants.

On the 20th anniversary of the Summer of Love and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the BBC produced a documentary about that era. Using the Beatles’ song of that summer, “All You Need is Love,” as a starting point, the producers asked, “Is love all you need?”

No, said radical leader Abbie Hoffman, we need justice.

It’s awareness we need, said poet Allen Ginsberg, because love arises from awareness.

LSD guru Timothy Leary said we need much more than love – we need intelligence, precision and an absence of discrimination.

And then they asked the question of George Harrison. He arched his eyebrow, calmly reached for the Bible on his end table and read this, from Apostle Paul’s letter to the Corinthians: “Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast. It is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking. … It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.”

Then Harrison closed the Bible, looked in the camera and said, “We stand by our story.”

Creating art allows us to beat the odds and find immortality, without having to do the whole Doctor Faustus thing. Buddy Holly, though dead two generations, is still young and hiccuppy when he sings “Rave On.” When we hear “Baby, Let’s Play House” by Elvis Presley, he is still fresh and beautiful and undeniably the King. When dancers gaze into each other’s eyes, they still hear the Drifters’ yearning, soaring voices telling of the wondrous moments up on the roof or under the boardwalk. Somewhere, someone is falling in love to Otis Redding singing “Try a Little Tenderness” and somewhere else someone is hearing Jimi Hendrix for the first time and realizing that rules are for losers. All of those voices are dead, but when we hear them crackling out of a car speaker today, they are forever young.

We can’t blame our musical icons for aging – we should celebrate them and revel in the glorious spectacle of generations changing hands. They’re the lucky ones. Think of the alternative – our absent friends Hendrix, Redding, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, half of the Beatles, two of the Beach Boys … (Think of them, but if you start to sing “Rock and Roll Heaven” I will leap out of this page and strangle you.)

Maybe we can learn from those still with us. Some of them are aging pretty darn gracefully. The Stones, remarkably, continue to roll – and they do it quite well. Joni Mitchell continues to blend her varied musical influences into a seamless, idiosyncratic fabric. Bob Dylan recently turned 65 and still manages to do onstage nightly what that other Dylan (Thomas) suggested: “Do not go gentle into that good night / Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Perhaps those of us who have clung so long to our youth can continue to learn something from our musical icons. Maybe, if we’ll listen to them and what they are saying now, they can give voice to our disjointed thoughts as we step closer to the Great Beyond. In his 20s, full of fire and fury, Dylan asked us: “How does it feel – to be on your own, like a rolling stone?” Today, in his 60s, he sings in acceptance: “Some of these memories you can learn to live with – and some of them you can’t.”

Artists do what they have always done – take the burdens of life and explain them, ease them or simply ponder them. They carry that weight for us.

Take a load off Fanny

Take a load for free

Take a load off Fanny

And . . . and . . . and …

you put the load right on me.

Originally appeared in The Tampa Bay Times, June 11, 2006