Thoughts on a Horny Poodle

The preface to Rock and Roll is Here to Stay: An Anthology (W.W. Norton, 2000)

The preface to Rock and Roll is Here to Stay: An Anthology (W.W. Norton, 2000)

In the summer of 1965, when I was 10, my family moved from Miami to Fort Worth, Texas. It was a hell of a caravan: a moving van, two cars, five people and five dogs. My father and teen-age brother were up ahead in the Triumph, packed into the tiny sports car with all of the house plants healthy enough to make the trip. My mother, my 16-year-old sister Suzanne, five poodles and I followed in the Cadillac, trying to keep up with the little red car and managing our own internal crisis. I sprawled on the back seat with the four female poodles, all of whom were in heat. My mother and sister comforted the remaining poodle, Walter, up front.

It was August, and well over a hundred degrees. We managed, for the four days of that epic journey, to keep Walter away from the girls. At rest stops, my sister held Walter while I struggled like some low-budget Ben-Hur, with four females straining their leashes. Walter moaned and tugged at his collar. His teeth chattered like typewriter keys.

Picture the view from the back seat: There was my mother, driving, pretending not to notice my sister, who was riding shotgun. Though Suzanne was seated, she was moving, doing whatever dance was popular that summer. Music came in a steady beat from the AM radio – and what great music: Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” the Beatles’ “Ticket to Ride,” James Brown’s “Papa’s Got a Brand-New Bag.” There was also Herman’s Hermits’ “Henry the Eighth,” but still … if the summer of ’65 wasn’t the high water mark of rock’n’roll radio, then I’ll eat my Chevy.

That summer was kind of like the Continental Divide in popular music. We could look back one direction and see the matching suits, the well-scrubbed faces and the kind of rock and roll innocence we’d never see again. Looking the other way, we could see the patched jeans, the dope-smoking, the songs about war and injustice that would reach the top ten, and a weariness underneath the thrashing power chords. And they started calling it simply rock.

That was a great summer on the radio.

Now that all of that great music is playing in your head, think of poor Walter staring at the back seat mournfully, machine-gun fire emanating from his teeth, watching and waiting for the moment I would doze and he would make a move on the four females. But I was a determined guardian of doggie virtue.

And what song, of all the great songs on that radio that summer, was the soundtrack of Walter’s frustrations?

It was a song by England’s self-proclaimed “newest hitmakers” that twanged out nearly every hour on the hour. As Suzanne writhed in the front seat and my mother pretended to passing motorists that she didn’t notice her daughter’s seizures, Walter gazed longingly at four sets of nubile poodle thighs, and an adenoidal wail blared from the tinny speakers, voicing the hound’s lament:

I … can’t … get no … I … can’t … get me no

No sat-iss-fack-shun

Over the years, when American mothers and fathers feared for the well-being of their children and regarded Michael Phillip Jagger as rock and roll Lucifer, corrupter of youth, leading the nation’s children down the path toward carnalities too bizarre to imagine, I could never see the grounds for their fears. Whenever vice-presidents or members of congress (or their spouses) prated about pop-music vulgarity and lascivious lyrics, they offered as evidence the Jagger-Richards song catalog.

When others conjured visions of evil too horrifying to mention, all the fault of the Rolling Stones, all I could think of was that horny poodle with the chattering teeth.

In spite of the poor dog’s frustration, that trip remains one of my favorite memories of childhood and, like so much of my life, it is informed by rock and roll. It’s as if my whole life has a soundtrack played by two guitars, bass and drums.

I was born the summer that Elvis Presley recorded “That’s All Right (Mama),” and so I am a true rock and roll baby, and I date myself with the use of that term: ROCK AND ROLL. It’s a wonderful name, isn’t it? The fact is, no one seems to know what to call this music anymore, but only aging diletantes such as myself employ the old rock and roll term. Rock and roll came into fashion in the 1950s. It became rock in the 1960s, then split into so many factions and divisions, that it’s hard to keep track. But I want to use rock and roll in this book. It’s such a wonderful thing to say. Go on, say it loud: ROCK AND ROLL. As Jerry Lee would say, “MMMmmmmmmmmmmmmm … feels good!”

When Elvis and his peers took over radio in the 1950s, the Hillbilly Cat and other early rock and rollers – Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and others – were condemned from pulpits across America and vilified by the press.

Nearly a half century later, rock and roll (in my broad definition: all popular music aimed at the youth market) still makes people mad. Rap has been drawing heat for a decade and the adjectives that used to be carted out for Elvis were dusted off and refitted for the 1990s: obscene, immoral, disgusting … high praise, of course, in the world of rock and roll. Tipper Gore tried to crusade against the bat-eating, blood-spitting headbangers in the early 1980s and rapper Ice T felt the Time Warner corporate squeeze when he produced a song called “Cop Killer.”

But there’s nothing really new about all of this. Ice T and the headbangers and the gangstas went from the magazine covers to the annals of rock and roll history pretty fast, seeming quaint just these few years later. If modern music was simply making people happy, it wouldn’t be rock and roll.

Rock and roll’s importance goes beyond radio playlists and album sales because it established itself in American culture as a forum for anger and rebellion. And that’s one of the reasons it’s in college classrooms as the subject of legitimate study.

I teach rock and roll history and defend my job with a straight face. As any other rock and roll professor will tell you (and we are legion; watch your back), Rock and Roll History is not a puff course. It’s nothing less than a far-ranging cultural history of America. We don’t offer the class to pander to the student audience and draw big enrollments. The course exists for a good reason: more than any other form of popular music, rock and roll has embraced social commentary. It has real historic value. From the start, the music made statements about culture. Its very sound – the raucous, anarchistic guitar, the pounding drums, the pulsing, subversive bass – was a protest against the smoother tones of mainstream popular music.

Elvis Presley isn’t thought of as a “political” artist, but his first single was a Statement because it combined the music of black America with the music of white America. Radio was segregated in 1954, but when Sun Records released that single, Elvis’s reinterpretation of rhythm and blues led listeners to the original sources. Those liberating radio waves didn’t recognize whether listeners were black or white. The air did not honor Jim Crow laws.

These musical walls began tumbling down the same year that the Supreme Court outlawed classroom segregation in Brown v. the Board of Education. The next year, when Martin Luther King began organizing the Montgomery Bus Boycott, rock and roll saw its first major performing songwriter, Chuck Berry, trying to consciously knock down racial barriers. Using a narrative style that borrowed a lot from country and western music – and combining that with a love of the blues – Berry created a distinctive syllable-crammed style with songs about experiences he knew both black and white kids shared. Berry’s songs were about things rarely considered fodder for pop songs: divorce from the kid’s-eye-view (“Memphis”); unappreciated Army veterans (“Too Much Monkey Business”) and statements of black pride (“Brown-Eyed Handsome Man.”). Berry wanted to entertain, but like a lot of rock and rollers to follow, there was a message in those chords.

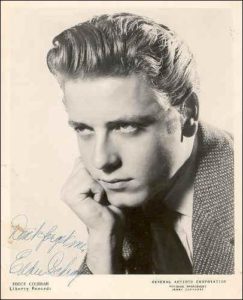

Whenever there’s talk of rock and roll’s social consciousness, it often centers on Bob Dylan, who did not begin recording until the 1960s. Yet before Dylan came along, the songs of Chuck Berry and Eddie Cochran made statements about teen-age angst. In “Summertime Blues,” Cochran played both kid and tormenting adult (lowering his voice an octave) in this famous passage:

I asked my congressman and he said (quote),

“I’d like to help you son but you’re too young to vote.”

So Dylan did not invent social commentary on popular music. That goes back to the beginning. It’s just that rock and roll embraced the idea more than any other strain of music except folk, and after Dylan came along in the early 1960s, things were never the same in rock and roll. Dylan knocked down walls between folk and rock and upped the ante for songwriters.

Dylan came into rock and roll from the folk music subculture and brought along an understanding of that genre’s long tradition of topical songs. He gained notoriety by singing epic ballads about racial murders and social injustice. When he began playing electric guitar in 1965 and hired a bar band to back him up, his songs – those unyielding demands for truth and honesty – put him at the top of the charts.

But Dylan and other performers of the mid-1960s had an advantage over artists here, at the turn of the century. They had an audience. Back then, radio was not as segmented as today, and listeners could hear rock and roll and soul and pop on the same station, one song right after the other. The Beatles followed by James Brown followed by Bob Dylan followed by Smokey Robinson followed by Frank Sinatra. Today, radio is so format-split that it’s a lot like the pre- rock and roll era of radio segregation.

In the 1960s, Dylan used music to chronicle two social movements. His finger-pointing songs about racial injustice were sung at scores of civil rights rallies, and his anti-war ballads were the soundtrack for the get-us-out-of-Vietnam campus demonstrations (oddly, though, Dylan didn’t use the word “Vietnam” in a lyric until 1985).

In the 1970s, the frightening and rebellious music of the Sex Pistols and the other punk bands was another wave of insurrection – this time, in part, against rock music that had become too corporate. Johnny Rotten and his band raged against the fat, happy rock stars who had once symbolized youth and swagger, but who then committed the sin of aging. Now Johnny and his gang are pot-bellied middle-agers.

In the 1980s and the 1990s, we again heard rock as an expression of anger with social conditions. The music asked whose cultural values were at stake. Rappers inspire the same outrage that got Chuck Berry in so much trouble back in the 1950s. (Berry was persecuted by the white establishment and did two years in prison.) Forty years later, rappers brought ghetto anger into white homes. The rappers’ words, delivered in machine-gun cadence, revive all the old rock and roll fears: Obscene … immoral … disgusting … Devil’s Music.

That means rock and roll is still on the job, working for you. If the music isn’t making people mad, it isn’t rock and roll. At least once a decade, rock and roll eats itself, and that process of reinvention is one of the things that makes it so much fun.

This book is not a definitive history of rock and roll. I doubt that such a thing could be done and make any real sense. To do a book like that, you’d need a shovel, not an editor.

What we do have here is testimony from some of the creators of rock and roll, some serious historical research, some brilliant criticism and a few artifacts. We have greatest hits (Tom Wolfe’s profile of Phil Spector, Jules Siegel’s tracking of Brian Wilson), some historical accounts (Peter Guralnick’s meticulous recreation of Elvis in mid-1950s Memphis, Alan Lomax’s memoir of song-hunting in the Deep South), some rock and roll reminiscences (Chuck Berry, Bruce Springsteen, Patti Smith) and some essays by great critics (Dave Marsh, Greil Marcus, Lester Bangs).

I recognize that not all of the great artists are discussed in detail. Alas, we had to leave out that favorite killer profile of Lothar & the Hand People. I wish that all the great rock and rollers could have been mentioned in this book. My guide in selecting the pieces was to walk the line between what was good history and what was good writing. And there had to be significant amounts of fun.

Rock and roll has always been about attitude. This book also has an attitude. The selections were made with an attempt to cover most of the significant developments in rock and roll, but beyond that general plan, I offer no guarantees. The music has inspired dogma, devotion and doctrine. These passionate pieces reflect that. One of the great pleasures of rock and roll has been reading all of the superb writing the music has inspired. We may question some of the writers’ judgments, but we have no doubt about their passion.

Copyright © 2000, 2020 William McKeen