To Live and Die in Dixie

Appeared in The Satellite, 2001

Being a reporter is a great life. In a way, it’s like having many lives because you spend your time writing about other people and you absorb their experiences.

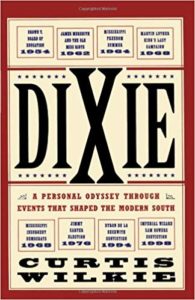

Curtis Wilkie has had a great life and, in Dixie, he intertwines his story with those of the people whose stories he’s told over the years as the Deep South reporter for the Boston Globe. This is no Rick Bragg rags-to-riches memoir of triumph over a hard-scrabble childhood (see All Over but the Shoutin’). Wilkie’s childhood was comfortable. But he grew up in the South a half-generation before Bragg and therefore witnessed most of the changes brought to the country in the aftermath of the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

In his simple, eloquent style, Wilkie recalls his growing up in Mississippi and how he went from accepting the status quo to fighting for change. This all took time – and the guidance of Wilkie’s fiercely admired mother, the wisdom of a good, decent stepfather who helped guide the boy after his father’s death, and the counsel of friends he made as a reporter who opened up his mind to social revolution.

Wilkie is a great reporter (he was one of the journalists profiled in Tim Crouse’s classic book The Boys on the Bus 30 years ago), but he’s also lucky. Great stories unfurled before him.

He was at Ole Miss when James Meredith enrolled as the university’s first black student. He palled around with some of the northern civil rights workers who came south to take part in Mississippi Freedom Summer. As a fledgling political reporter, Wilkie followed the story of the Mississippi Freedom Democrats challenging the old guard at the 1968 national convention.

Martin Luther King, George Wallace, Lester Maddox – they’re all here in Wilkie’s book. So is Sen. Robert Kennedy. Visiting a shack, Kennedy finds a young black child whose only food is a spoonful of molasses. The boy crawls over the floor of the family shack in his soiled diaper, picking at chunks of cornbread scattered on the floor. “Flies were swarming,” Wilkie writes. “Kennedy knelt by the child and gently stroked his face for two minutes without saying a word. The boy just looked at him with wide eyes.”

These small moments show the big truths, as the South changed during Wilkie’s life. He tried to leave the South as he moved up the newspaper food chain – he went from the paper in Clarksdale, Miss., to national-political-reporter heaven with the Boston Globe. Yet even up North, he couldn’t escape the South. He covered the Carter years and discovered a strange, unexplained antagonism with his fellow Southerner. Even when Wilkie was assigned overseas to cover the wars in Lebanon, the scent of magnolia still lingered. He saw so many parallels with his experience that his nickname for the Middle East was “Dixie.”

The inevitable homecoming followed. Wilkie nows covers the South from a homebase in New Orleans and burns up the road to Oxford for all of the Ole Miss home games. Of all the stories he’s told in his career, perhaps his story was the best. And of all the places he’s lived, the South still feels like home.