State of Emergency

Another abandoned project. This was for a. book to be called The Politics of Weather, and I can’t really tell you what that title meant. I just wanted to write about the weather. I spent some of my growing up in Florida and lived through several hurricanes. As an adult, back in Florida, I lived through that year when we (north central Florida) got hit by an assload of hurricanes. At least, I helped conceive a son out of the deal. Hurricane Charley begat son Charley, though he was named after a plethora of Charlies/eys on both sides of the family and, of course. Charley Patton, founding father of rock’n’roll.

. . . . . . . . .

Copyright © 2024 William McKeen

They called it “God’s waiting room,” and during those years when the chamber of commerce kept such statistics, it had more park benches per capita than any other city in the United States. The green benches symbolized the town’s reputation as the geriatric capital of the world. Men and women worked their whole lives in Findlay, Ohio, and Moorhead, Minnesota, dreaming of retirement to the orange-blossomed heaven of Florida, only to end up in a used single-wide on a grid street in St. Petersburg, Florida.

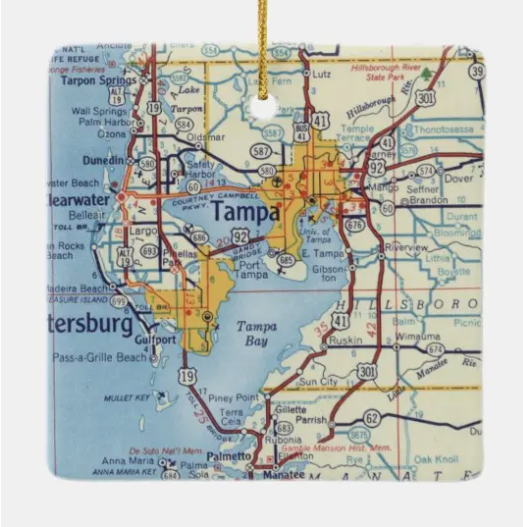

St. Petersburg is on the lower half of the Pinellas Peninsula, a bulbous beak along the Gulf Coast, forming the westward rim of Tampa Bay. It connects to South Florida by a spectacular bridge called the Sunshine Skyway. On the north, a narrow tube of land links St. Petersburg and its neighboring city, Clearwater, with the bucolic horse country of North Florida. Three causeways, the Gandy, the Frankland and the Courtney Campbell, tether St. Petersburg to Tampa, across that shining bay.

Pinellas County was out there on that knuckle of land. Like the rest of the state, which resembles a dormant penis dangling from the southern coast, Pinellas was geographically vulnerable.

The fragile exit to the south, the Sunshine Skyway, was five and a half miles long and 431 feet above the water. A freighter hit the original Skyway in 1980, knocking down one section of the bridge, sending 10 cars and one Greyhound Bus into the water. Thirty-five people were killed.

Even rebuilt, the Skyway is not the sort of road to inspire confidence. In the middle of the bridge, stiff wind blowing, you fight to keep your car in the right-hand lane. No matter what the traffic, you’re out there alone, and helpless. You can’t drive over that bridge without imagining that busload making the big plunge.

Going north on Highway 19 is only a little better. The road is notorious for bumper-to-bumper traffic even on a slow day, even in the middle of the night. It quilts together miles and miles of strip malls, fast-food joints, liquor stores, in exactly the sort of landscape for which the term “urban blight” was coined.

The three routes across the Bay are often used car lots, even on beautiful, cloud-free days, with tailgating drivers, honking horns and cell-phone jabber, all the elements of another traffic nightmare.

Every summer, the St. Petersburg Times, the fine local newspaper, does its civic duty by warning the city of its vulnerability to nature. Hurricane Season begins each June 1st with the same warning across the Southern United States, but the Times speaks with a particular urgency about its community. With so few ways off the peninsula, and with so many residents elderly and dependant on others, the jeremiahs of weather forecasting said the city was one Category Four away from an apocalypse.

For St. Petersburg, there were only five major escape routes in the event of an evacuation order ahead of a killer hurricane.

The hurricane season that started June 1, 2004, would become one of the most deadly since statisticians began keeping records. With that fragile road out to the south, and the vile asphalt miasma up Highway 19 to the north, exits were limited. Most of those fleeing St. Petersburg and the wrath of a biblical storm would be stuck on those causeways that ribboned Tampa Bay. It was, as the Times annually said, a nightmare waiting to happen.

The season’s first storm became Hurricane Alex at two in the morning on August 3rd. As a Category Two tropical depression, it flirted with Florida’s Atlantic coast, finally moving north and skirting the Outer Banks of North Carolina.

In Florida, the storm barely got notice. Ho-fucking-hum.

The second tropical depression did cartwheels in the southern Caribbean for a week before becoming Tropical Storm Bonnie. It traveled straight up through the gut of the Gulf of Mexico, but by the time it made landfall in the Florida Panhandle at Apalachicola, it had piddly 45-mile-per-hour winds. Killer hurricane, my ass.

The third tropical storm had formed the week before and had been steadily acquiring strength as it became Hurricane Charley on the afternoon of August 11th.

By this time, residents of St. Petersburg and Tampa were laughing off another near miss by piss-poor Bonnie, leaving the Bay Area only slightly brushed. As Bonnie made landfall, Charley was slamming the southern coast of Jamaica, then preparing to hit Cuba.

After it rolled over Cuba and came back out over water, Hurricane Charley was a Category Three storm with 120 mile per hour winds.

In Key West, the southernmost city in the United States, the townsfolk took notice. Even St. Petersburg could not feel as vulnerable as the residents of the two-mile-by-four-mile rock island at the end of Highway 1. Some residents evacuated, pointing their Bonnevilles up the two lanes north, where they’d stop-and-go it all the way to Miami. But a cadre of hard-core Key Westers stayed put, hunkered down, and prepared to ride out the storm with margaritas in hand. They were a tough bunch.

They lucked out. As Charley left Cuba, the storm made a wide loop around Key West and into the Gulf, where it gathered strength from the warm waters of the tropics. It didn’t even give the Keys a glancing blow.

And then the storm took a bead on St. Petersburg. By early afternoon on August 13th, Hurricane Charley was a Category Four storm bearing down on the fragile Pinellas Peninsula.

The apocalypse is arriving from the west.

Television and radio begin the bug-out mantra. For God’s sake LEAVE – but if you don’t, board up and get some bottled water.

Orderlies gas up the vans for the assisted living centers. In the lounges, the residents circle their walkers, muttering darkly about the storm and whether there is time to get on the highway to get out of harm’s way.

Moms and dads pack up their mini-vans and their children, make calls to aunts and uncles in South Georgia, and join the flood of humanity going north on the clogged arteries of the Bay Area.

The traffic jam begins as cars head east, across the Bay, to Tampa and the interstate north. It’s bumper-to-bumper, as usual, up that foul stretch of Highway 19 to the rolling hills of Pasco County.

Thousands of lunatics adopt that Key West bonhomie and plan to ride it out, but as the news reports become grim and clench-jawed serious, even they wonder if this might be it.

It was that day the newspaper had been warning about for a generation: The Big One is here, knocking at the door.

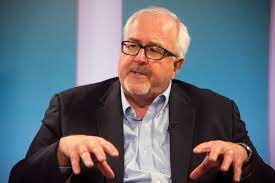

Two-hundred-and-fifty-seven miles up Highway 19, Craig Fugate sat at his desk, wondering what it might take to get the people of his home state to take nature seriously.

It wasn’t an idle concern. As the head of the state emergency management agency, Fugate directed all things hurricane related from his office at the state capital in Tallahassee. Forty-three miles inland, residents of the capital felt relatively safe. Folk wisdom held that once these big-bastard storms hit the coast, they died quickly and that towns that far from the coast were secure.

Fugate had heard that sort of folk wisdom all of his life, since he was a Florida boy from the village of Alachua, smack-dab-in-the-middle of North Central Florida. Relatively equidistant from the water – 71 miles to Cedar Key on the Gulf, 85 miles to Crescent Beach on the Atlantic – Alachua had the sense that it was immune from the yearly threats of hurricanes that had ravaged the coastal parts of the state ever since the Calusa Indians inhabited Florida during the prehistoric era.

Fugate knew otherwise. He’d spent most of his career out in the field, pulling people from their wrecked homes, retrieving bodies, and telling mothers that their children were dead. He was not a career bureaucrat and, if there was one thing chafing him right now, it was this desk, this fine mahogany where he’d been put by Governor Jeb Bush. He had his paperwork to do, and his phone calls to make, to be sure that all of his people were in place for when the storm made landfall. He’d be in the field then himself, to oversee operations. But for now, there was that last bit of paperwork.

Fugate had been an unusual pick for the Republican governor. A life-long Democrat, he didn’t fit the profile of most of Governor Bush’s appointees.

Fugate had the reputation of a no-bullshit go-to guy. He was a soft-spoken mild-mannered embodiment of the motto of Larry the Cable Guy: Git ‘er done. You want something done, you get Craig Fugate on the line.

And this fall was an election year for the governor’s brother. Bloggers watched the hurricane season with delight expecting some massive clusterfuck from Governor Bush, something that would tarnish his big brother, the President of the United States.

“Forgive me,” one blogger gleefully wrote on August 12, as the storm prepared to make its first landfall, in Cuba, “this is macabre. However, with Charley poised to hit the Florida Westcoast [cq] head on, we have the makings of a huge POLITICAL story. The Bush Brothers had better be there for the aftermath of the storm. There will be a huge disaster if the storm hits where the projections predict. There is little doubt that President George H.W. Bush lost Florida in 1992 because of poor execution of Federal response to Hurricane Andrew the year before. . . . The Gov. and the President better have rubber boots, parkas and better be prepared to live alongside people in shelters. If they fail to respond it will be lights out in Florida for Bush-Cheney and possibly the election as a whole.”

To much of the press, who painted the pictures for the general public, the governor had an arrogant, aloof, standoffish aura. Where the hell was he from, anyway? These Bushes . . . were they from Maine or Texas or Connecticut or what? They had a geographic identity crisis. Then one of them turns up in Florida and becomes governor, sort of a green-room job until his brother hands him over the White House.

So there was a lot riding on this as Hurricane Charley churned toward that fragile finger of St. Petersburg. The governor’s future, if not the presidential election, all depended on how well Fugate did his job.

Fugate was born in 1959 at Jacksonville Naval Air Station, where his father, a Navy veteran, was stationed. When he was 10, his mother committed suicide. His father was overwhelmed and since he was still in the service, couldn’t cope with a family without a wife. So Craig and his two older sisters were sent to live with grandparents in Alachua.

When Fugate was 15, his father died.

Life continued in Alachua, and Fugate grew up with his grandmother, a clerk at the Alachua Post Office. “She was great,” Fugate said. “Everybody knew her both as my grandmother and a surrogate grandmother to everybody.”

While he was still attending Santa Fe High School, Fugate became a volunteer firefighter, and that set him off on his life’s course. He would eventually attend Florida State Fire College, just down the Interstate in Ocala, then become a fire department lieutenant for the Alachua Fire Department. That led to 10 years as the emergency management chief for Alachua County, which included the much larger town of Gainesville, the home of the University of Florida.

He worked out of a cramped basement office when he ran the emergency agency, and adopted the two-minute manager style of leadership. He called what he did “thunderbolt” exercises: he’d walk into an employee’s office and say, “OK, there’s a fire in the building and you have to evacuate. What do you do?”

Fugate’s scarred childhood could have embittered him, and he could have become one of those angry, tattooed yeehaws cruising Highway 441 in a battered F-250, tossing his Bud Light empties out the window, pissed off at the world that things didn’t go his way. Instead, he who grew up needing help, decided to make it his life mission to help others.

“I just do stuff,” he shrugs, characteristically modest. “Everybody tries to attribute it to something in my background, something in my family. I’m more Zen-like. I don’t know if there’s a reason.”

In 2001, Governor Bush asked him to run the state’s emergency management agency.

And now, three years later, as the storm closed in on his home state, Fugate finished with the paperwork and phone calls, pulled himself out from behind the mahogany desk, and got into his truck in the state capital garage. With his convoy of colleagues, he headed south, toward Tampa Bay.

It’s a forty-foot oak, but it’s doing an approximation of a discothèque dance from the 1960s. Look at it move: it’s upright, then it slams its upper branches down to the ground, like a lanky Twiggy wannabe doing the frug or the jerk. Then – boom – it’s upright again. There’s a lull, then a repeat. Again the frug.

Watching the writhing tree out the window, Fugate marveled at the endurability of this magnificent creation. As a child, he used to lie on his back in his grandmother’s yard and look up at the sky, his view bordered by the massive live oaks shooting from the ground, arching into the sky like rockets, then held in place against the iridescent blue.

Sometimes he’d lie there and see the trees as if he’d never seen things like them before. They looked extraordinary and alien from that angle.

He never lost that ability to see things with those eyes, and with those virgin sensibilities. Even in the middle of this natural disaster, he had to pause a moment to admire the strength of these creations.

He was in Fort Myers. At the last moment, the storm had made a turn to the east, sparing St. Petersburg and Tampa. Fugate was happy that the massive hurricane wasn’t going to be ripping through one of the most populated parts of the state, but he also knew that this near-miss gave all those folks in Tampa Bay that dangerous feeling of invincibility.

He’d been putting out his usual message: evacuate; board your windows; hoard bottled water; pack lots of peanut butter. And now those hearty fools who didn’t listen to those evacuation orders or make any preparations laughed again at caution. Sure, they might be inconvenienced by short-term power outages, but nothing would make them bug out.

Fugate worried that to a lot of those foolhardy Floridians, he was like the little boy who cried ‘wolf.’ They got used to it and paid no attention, so when the wolf was finally at the door, they wouldn’t be prepared.

For three days, he didn’t sleep, monitoring both his crews of state workers and local agencies. Because he’d come from the trenches, from being a volunteer fireman, and not from some management program, Fugate was enormously popular with the rescue workers on the ground. He knew where they were coming from and in turn, they respected him.

As he snaked through the streets of Fort Myers, avoiding the splintered trunks of those weaker trees that couldn’t maintain the dance, he listened to the constant squawk of his intercom, as it told of men trapped under debris, power lines down, cars stuck in ditches.

The day after Charley came through was beautiful: a cloudless sky and a warm, beautiful sun. It was another sign of God’s sense of humor, Fugate thought. I will rein great agony upon you, and then will reward you with locusts and wild honey. People came from the shelters, blinking like moles in the over-bright day, the better to see the disaster visited on all of their worldly belongings.

It was Fugate’s job to make sure that everyone was accounted for and in a safe place. Some wanted to be in their homes, no matter what their condition. They didn’t care about navigating the downed and dangerous power lines or the fact that they no longer had running water. The instinct to nest, to be home, was strong.

Charley had cut a diagonal across the state, giving Orlando – that sprawling urban mess right in the middle of the state – a severe shock to the system. For a day, Disney World closed. No one could ever remember Disney World closing.

So much for the folk wisdom. With a hurricane this powerful, inland towns and cities were not spared.

But something about disasters brought out the best in people, Fugate thought. He knew there would be looters. Down the way, there would be contractors and roofers who would prey upon the victims, but as he drove through the streets of Fort Myers and Port Charlotte, he saw random acts of kindness: one family sharing a jug of bottled water with neighbors who weren’t prepared. There was a lot of sharing – of food, of shoulders to cry on, of stories to tell about Hurricane Charley.

Fort Myers was a wealthy community, with a lot of retirees and two northern Major League teams each March for spring training – the Boston Red Sox and the Minnesota Twins. By contrast, Port Charlotte was much more of a working-class community, 20 miles south and without the culture and retiree night life of Fort Myers.

It was a small town with a lot of continuity. The same family, the Dunn-Rankins, had owned the local newspaper for 37 years. The boss of the paper, then in his late seventies, was the spry, crew-cut Derek Dunn-Rankin. His son David, though nearly fifty, was still the No. 2 in command.

With the newspaper at first unable to distribute in its normal way, the Dunn-Rankins took to the air, broadcasting non-stop all of the information the community needed about shelters and places to find bottled water. They gave out cell phone numbers and directions on the air, and opened the airwaves for people to call in and tell their stories.

And when other publishers in their position might suspend publication to cut their losses, Derek Dunn-Rankin got the presses working and increased the press run so that everyone in the circulation area got the paper, whether they paid for it or not.

Like all public officials, Fugate had the occasional run-in with the press. He was always careful in dealing with journalists because he knew what an important role they played in getting safety messages out to the people.

But inevitably, they got it wrong.

As he paged through the thin issue of the Sun-Herald the day after Charley hit – there was hardly any advertising – Fugate admired what the Dunn-Rankins had done.

They got it right.

Hurricane Charley ripped the guts out of Florida’s southern Gulf Coast. It made landfall at Cayo Costa, just north of Sanibel Island, the idyllic vacation destination. Upon impact, it had 150 mile per hour winds. When it hit the mainland, across the channel at Punta Gorda, the winds were still significant, at 140 miles per hour.

For Charlotte County, the storm was deadly. It would eventually be ranked as one of the worst hurricanes in world history, falling just outside the “top ten” of weather catastrophes.

Fort Myers and Port Charlotte were beaten nearly beyond recognition. Before Charley’s run across Florida was through, the storm caused $13 billion in damages and ten deaths. After the hurricane hit Orlando, it spit itself back out into the Atlantic near Daytona Beach.

Charley was nothing if not thorough.

St. Petersburg and the rest of the Tampa Bay area were again spared the promised meteorological apocalypse. Despite the fact that the governor, on Craig Fugate’s urging, had issued an order urging two million people to evacuate, few of the 380,000 in the Tampa Bay area chose to do so.

Before the state could recover from Charley, Hurricane Frances attacked the other side of the state, coming ashore at Palm Bay, meeting the last gasp of Charley’s destruction in midstate.

And now, within the same month of that one-two punch, a Category 5 storm named Ivan was churning through the Gulf of Mexico, heading for the Redneck Riviera, that expanse of cheap motels and sleazy bars that stretched across the Florida Panhandle and into the beaches of Alabama and Mississippi, which were modest in size but truly full-service in terms of booze and babes during the season.

As the relentless storms battered Florida and the Gulf Coast that fall, Jim Cantore was one of the most-watched men in America. He was on the Weather Channel nightly, his black T-shirt stretching tight to contain his roiling biceps. The dude was buff . . . ripped . . . yeah, man. The Weather Channel demographic tilted largely female in the evening and the network’s brain trust figured that Cantore — heaving pectorals and an iron jaw, cool and confident — was the main reason. Middle-aged women, married or not, curled up with their glasses of pinot noir in the living room and watched Cantore, standing tall in the mother-loving wind, talking about millibars and beach erosion and miles per hour. They melted when he looked into the camera with those strong, Sicilian eyes. Bald by choice and middle-aged, he still managed to draw the swoons. They had a name for him, these women. They called him the Hurricane Hunk.

Television celebrity or not, he still had to sludge through the vagarities of life in an evacuated vacation community. He’s shooting his stand-up cut-ins tonight on the balcony of his second-floor Days Inn room in Panama City, Florida.

This is the town that Spring Break made. Each March, Panama City was wall-to-wall hormones and vomit. Each night, young men groped young women in bars, got laid, and drank until they puked (after the consummation of the nightly relationship, if possible). The next day, the ritual was unfurled again, usually with a new partner. Rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat.

And then, after a week of debauchery, the vanloads of young scholars headed up Highway 231, back north to Michigan State, Colgate or Sarah Lawrence. On the way out of town, they’d see the next week’s army of spring breakers on the way down for their week in the low-rent paradise.

The townsfolk tolerated the month of college-kid revelry and massive inconvenience because it propped up the Panama City economy for a full year. A lot of locals scheduled their vacations to coincide with the arrival of the Spring Breakers, but they went the other direction: to Breckenridge or Telluride or Sun Valley. The best way to deal with the carnal atrocities was to be gone.

There were some fine hotels in Panama City and, not far down the coast, Destin beckoned with resorts and room service and full-service spas.

But here was Cantore, the Hurricane Hunk, ogled by millions of women at just this moment, and he was standing in a buffeting wind on the balcony of a dog-ass Days Inn in the capital of the Redneck Riviera.

“You can look behind me here and see the rain bands coming in,” he said, doing the Ed Sullivan sweep with the arm. “This thing is still a long way away from us. But once it makes that turn, it could start to speed up. We’ll continue to track Hurricane Ivan as it heads closer. And we’ll keep you posted.”

Cantore had been on the air for a brain-fagging run of 8- to 12-hour days. Five weeks of this so far. He hadn’t made it home for a weekend in all of that time, seeing his wife and kids maybe one night a week in the last month. Unlike the typical married-to-the-job father, Cantore was eaten away when he couldn’t be with his family.

His wife, Tamra, suffered early-onset Parkinson’s disease and his two children had what’s called Fragile X Syndrome. Their X chromosomes don’t work. It’s a mental impairment mimicking Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

They discovered Tamra’s Parkinson’s — the type for which there is no cure — when they first took their son in for testing when he was 18 months old and still hadn’t started walking. The storm was on them quickly. Tamra, and Christina and Ben needed him desperately, but his job and his duties were as volatile as the weather.

That fall’s hurricane season had been a killer. After he finished his stand-up at the Days Inn, he bypassed the cold pizza still left on the dresser — the crew got first pick — and called his home in Atlanta.

Keeping his voice low, he stole a few minutes alone with Tamra. It was the best he could do to catch a shred of privacy, but there were four men crammed into a muggy room overlooking a hellish scene out in the Gulf.

“You had salmon Alfredo for dinner?” Now he was talking to Christina, his 11-year-old. “That sounds yummy.” Pause. “No, I haven’t had dinner yet.”

Then Tamra got on the line to say Ben wanted to talk. Alert the media! Ben doesn’t do phones. A conversation with Ben usually lasted 10 seconds and was mostly hi and bye, but tonight Ben yammered like any other nine-year-old, going on about video games, the Yankees and cabbages and kings. The boy’s days were collections of highs and lows and Cantore was giddy, catching the kid at a Himalayan peak. Cantore’s so happy, he feels tears at the corner of his eyes. For a moment, he smiled. He was a father again, doing the back and forth with his son. They share a love of baseball and Cantore longed to take his boy to a Yankees game, but he can’t. Ben has meltdowns in crowds.

Then Ben asks The Question and Cantore’s face darkened.

“I’m still waiting for this storm,” he said wearily. “I’m going to be home . . . Well, I hope on Friday, Buddy.” He closed his eyes. That’s four more days, Buddy told him. “Yep,” Cantore said. Four more days.

When they dined together, Cantore had to cut up his wife’s food in order for her to eat. When he was on the road, he had someone stay with his family, but that didn’t keep him from worrying.

Cantore’s first job out of school — he graduated from Lynden State College in Vermont, class of 1986 — was at the Weather Channel. He met Tamra his first day on the job. She worked in the Weather Channel’s sales and marketing department, and her assignment was to make Jim Cantore a star.

She did, and also made him her husband four years later.

They both worked on the road – him as the storm-chasing hunk, her as the person marketing the network to cable systems around the country – but she slowed down once the children were born. After the diagnoses were made, life changed at home but for Jim Cantore, the demands on his time, and his life as a storm chaser, were still ramping up.

He was outside now, on the Days Inn’s tiny beach, talking to millions as the horizontal rain whipped his face and the wind tried to tug his “Storm Stories” hat from his head. He’ was not above plugging his weekly documentary show. Now he was swaddled in his specially made Gore-Tex Weather Channel windbreaker and speaking clearly to be heard over the tugging wind.

“The good news is that any potential landfall won’t come here until Wednesday.” His dark Sicilians gazed resolutely into the camera. “That means you’ll have plenty of time to prepare.

He couldn’t help that he was good looking or that middle-aged women drooled over him. He was serious about his work, hammering home on every set-up the need for preparation, for evacuation, if necessary, and that once the storm blew through, there’ would still be a lot of other stuff to worry about, such as beach erosion and long-term ecological damage.

When the Channel went to break, Cantore didn’t refresh himself, but instead intently studied the radar for further clues. The storms had done so much damage inland, he wondered what would happen if one of these big bastards hit the Georgia coast, then beelined for the sprawl of Atlanta. Would he be able to help his family or would he be needed for another one of those live 12-hour air shifts?

“Hey Cantore! Up here!” He looked up from the radar screen and saw a fan, someone outside his demographic. It wa a big guy with a belly the size of a Firestone, and he was waving at him from a fifth floor balcony. “We love you man!”

Cantore waved back. “Who’s winning the Broncos game?” he yelled.

“We don’t know,” the man yelled back. “We’re watching you.”

Two days later, Ivan was declared a Category Five storm and was the approximate size of Texas, circling menacingly out in the Gulf, taking his time coming ashore.

Cantore was back on the air. He tried to slog through the celebrity and the show business part of his job and fulfill his mission as a meteorologist.

“All right, folks, here’s the deal,” he started. “This thing is coming. It’s going to be making big waves in the Gulf here soon. This is a tremendously dangerous hurricane, people. If it stays at five, we’ll be under water, even on the second story of this motel.” He lets that sink in. “For now, I’m meteorologist Jim Cantore, reporting live from Panama City Beach, for the Weather Channel.”

Five of the named storms of the 2004 hurricane season made landfall in Florida. There were 3,132 deaths attributed to the hurricanes, three thousand of them alone in Haiti, where Hurricane Jeanne tortured the impoverished island before hitting the United States. In the aftermath of the hurricanes, flooding in the South was at record levels.

Hurricane Ivan veered westward from Jim Cantore’s Weather Channel crew, eventually making landfall in southern Alabama. But after hitting Alabama, parts of the storm spun back out over the Gulf of Mexico and made another landfall in Southern Florida, though as a much smaller storm.

Ivan caused $18 billion in damage to the United States and was ranked the 10th worst hurricane in American history.

Craig Fugate acquitted himself well. The state had been horribly battered by an unprecedented series of hurricanes. No one area of the country had ever been so brutalized by severe weather, it was as if Mother Nature was pissed, and she was pissed at Florida.

Fugate couldn’t even breathe a sigh of relief when the hurricane season ended on November 30. A late tropical storm named Otto was causing trouble when all the hurricanes were supposed to be upstairs in bed. Otto kicked up a fuss and made a nuisance of himself, but was nearly a comic relief after the tragedies of the fall.

He could congratulate himself after getting through the season of hell, but Fugate had no idea that the frenzy of that fall would end up being but a dress rehearsal for the nightmare to come with the killer hurricane the following year. Again Fugate would acquit himself, and show leadership that brought him to national attention and earn him a seat at the table in the next presidential administration.