Man in a White Suit

I published a book on Tom Wolfe back in 1995. I’d always admired him. (Click here for a reminiscence of helping him research for one of his novels.) After his death, I wanted to expand that earlier book into a full-blown biography, in my mind a companion to Outlaw Journalist. Alas, that never worked out. Here’s something I wrote while researching the book. Consider this a sort of “Literary Journalism: The Early Days.”

. . . . . . . .

Copyright © 2024 William McKeen

Pete Hamill is sniffing around, doing a piece for Nugget, of all things. Seymour Krim is the new editor, trying to turn the skin mag into something respectable, something in the Zip Code of mid-brow lit. It’s a hard slog for Krim, a real up-from-booty journey (Recent Nugget cover lines: “Manhattan and the Promiscuous Girl” and “Pornographic Art Comes of Age.”), but he’s determined to make the rag respectable. Still, no shaking in the boots at Esquire.

As part of Krim’s perversion conversion, he decides he wants an article about what’s going on with journalism in New York, something serious that recognizes the strange pyrotechnics in the newspapers and magazines. We have Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese and Jimmy Breslin and just about anyone else who knows how to type doing some weird things in print. This, he figures, is the thing to bring Nugget out of the vast below-the-waistland.

Krim assigns Pete Hamill, a New York Post guy just back from Europe, where he wrote for the Saturday Evening Post. That magazine, the epitome of respectable, modestly calls itself “an American Institution.” But the Post is nowhere near hip, and hip is important to a young buck like Hamill in 1965. On that respectable-to-hip continuum, Nugget is pretty far down the scale from the Post, so Hamill grabs the assignment from Krim. It’ll be easy, he thinks. After all, he’s writing about his friends.

So tell me about it, he says to Wolfe when he calls, tell me about the New Journalism.

The what?

As far as he could remember, that was the first time Tom Wolfe heard those words together. Immediately, he felt dread. Anything with a “new” tag, he thought, was doomed to failure. All this stuff he was doing and watching and seeing explode all around him, it would be over before it began. Once someone called it new, it was doomed.

Yet not only did the term catch on, it held on for a decade before it assumed a new name. Along the way, it got capitalized and when Wolfe wanted to create an anthology of this kind of writing, he called it The New Journalism. That book began with forty pages of Wolfian manifesto, followed by a selection of key examples from Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, Barbara Goldsmith, Hunter S. Thompson, Wolfe’s hero (Gay Talese), as well as two selections by Wolfe his own bad self.

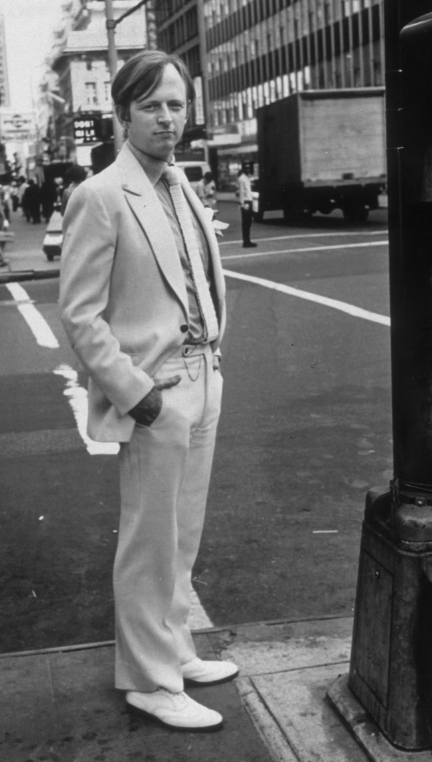

By default, in those early days, Tom Wolfe became Mister New Journalism. Because of the white suit and his well-mannered loudmouth ways, he was the most prominent figure. He was the well-coiffed talking head called on for the television shows and for magazine features. His wardrobe was a good interview. He was a one-man instant-publicity machine.

And besides: Gay Talese didn’t go in for self promotion. Joan Didion was pathologically shy. Terry Southern was too busy churning out screenplays and Truman Capote wanted to call what he did something else entirely.

So whether he wanted to or not, Tom Wolfe served a dual role in the world of New Journalism movement of the 1960s: he was at once its most celebrated and prolific practitioner and its reluctant historian.

As it turned out, Wolfe’s scholarly training had not been for naught. A decade after he landed on the national table, he produced the New Journalism anthology, acquitting himself as an essayist and anthologist, with a book that was both a history of the form and a collection of some of the best literary journalism to that date.In that great look back — published in 1973 — Wolfe talked about the early days and fumbling around, trying to find his voice, and what he drew from his colleagues. They weren’t colleagues in the usual sense in that they worked the next desk over. (Though the next-desk-over at the Herald Tribune was likely to be occupied by Charles Portis, the future author of True Grit, or sports laureate Dick Schapp or the criminally underrated Jimmy Breslin.) To Wolfe, his colleagues were those writers who were — to use a phrase he would later introduce to American grammar and usage — pushing the envelope.

When he published The New Journalism, Wolfe took the opportunity to gaze upon his earlier self and thank those other envelope pushers who had inspired him and helped him slip a joy buzzer to the world of newspapers and magazines.

After Wolfe, the major characters were Gay Talese, Capote, Gloria Steinem, Norman Mailer, Joan Didion and Hunter S. Thompson. Others – primarily Breslin and George Plimpton – also played a part. Yet there was little unanimity among even this small group of writers.

Capote and Plimpton were bona fide members of the literary establishment already inflamed over Wolfe and his “bastard form,” still seething over the New Yorker parody / takedown Wolfe published in 1965. Plimpton was so gifted in diplomacy that it’s a shame he never was asked to broker peace in the Middle East. He stayed in the New Journalism fray while remaining a card-carrying literary figure, owing to his role as Paris Review editor.

Capote also kept himself distant from Wolfe, though he was a true journalism revolutionary. Capote saw himself as rescuing the craft and creating a new art form, so he forged ahead, rarely glancing Wolfe’s way.

Nevertheless, this small but disparate group was redrawing the lines in the literary turf wars.

In the essays in The New Journalism and the introduction to The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby – along with the frequent speeches he made on the subject – Wolfe was not falsely modest in describing his role as the man who was shaking up both the journalism and literary establishments, but he was always lavish with praise of these others and their experiments.

In 1972, Wolfe turned journalism historian with the publication of articles on the early days of New Journalism that appeared in New York and Esquire in 1972. These four pieces were sewn together for his text in The New Journalism and allowed him a pulpit from which to rail against the writers of fiction whose self-indulgence had forced fiction to lose its mass audience and forfeit the role as the pre-eminent form in American letters.

Although he cited many 19th Century examples of what was he thought was bogusly known as “new” journalism, Wolfe said the form came to the forefront in the 1960s because modern novelists tossed aside realism in favor of an inner-circle contest to write for an audience comprised almost entirely of other writers.

Wolfe’s idols didn’t live in his century. His journalism, he said, was inspired by Charles Dickens, James Boswell, Honore de Balzac and William Makepeace Thackeray. Wolfe often Dickens’ Sketches by Boz as an example of the use of fictional techniques — reliance on dialogue, using scenes rather than exposition to propel readers through the story — in the telling true stories. So you see, Wolfe often said, there was nothing at all new about New Journalism. These journalists, these proles, merely scooped up what the novelists had discarded, the tricks of the trade.

One of the more modern antecedents for the writing that exploded in the 1960s was John Hersey’s 1946 book, Hiroshima. Hersey, a Yale graduate and part of the Time magazine machine, broke from the dictatorial confines of Henry Luce’s publishing empire after the war, when he visited the decimated Japanese city after the atomic bomb was dropped and wrote about the weapon’s effects on eight residents of the city. Hersey did not even attempt to publish the piece in Time.

There was a basic difference of opinion on the meaning of the atomic bomb. To Henry Luce – and, therefore, to Time, Inc. – the bomb symbolized American superiority and technological genius.

To Hersey, the bomb represented the most horrifying manifestation yet of murderous technology. He wanted to take the abstract (faceless victims of the destruction) and make it concrete (six people we come to know in the course of his book). Hersey, with the skills of a fine novelist, described what Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the East Asia tin works, was doing when the bomb was dropped:

Just as she turned her heard away from the windows, the room was filled with a blinding light. She was paralyzed by fear, fixed still in her chair for a long moment (the plant was 1,600 yards from the center [of the blast].) Everything fell, as Miss Sasaki lost consciousness. The ceiling dropped suddenly and the wooden floor above collapsed in splinters and the people up there came down and the roof above them gave way; but principally, and first of all, the bookcases right behind her swooped forward and the contents threw her down, with her left led horribly twisted and breaking underneath her. There, in the tin factory, in the first moment of the atomic age, a human being was crushed by books.

Hiroshima appeared first in The New Yorker as the entire editorial content of one issue. Published in book form in 1946, it remained a perennial English-class text and steady seller. No one employed the term “new journalism” to describe it in 1946, but Hersey did all of the things that were in vogue twenty years later: he wrote non-fiction as if it was fiction. Except for the fact that the scenes described were true, Hiroshima read like a smartly done, darkly fascinating novella.

The New Yorker was a showplace for much of the writing that later years would reveal as having been New Journalism.

Lillian Ross was hired by the magazine’s founding editor Harold no relation Ross. Novelist Truman Capote was interested in writing non-fiction and in 1955 accepted an assignment from the magazine to accompany a troupe of the Gershwin brothers’ Porgy and Bess tour, with State Department sanction, behind the Iron Curtain.

With a tremendous ear for unintentionally funny dialogue and a novelist’s gift for selecting detail, Capote stayed out of the action and watched as this puzzled troupe of actors wondered why these great Gershwin tunes were getting no reaction from the Russian audiences. Finally, they realized the problem: Since few in the audience spoke English, the performance was incomprehensible. Capote’s account appeared first in the magazine and then in 1955 as the book, The Muses are Heard.

So there were many precedents before that momentous day in 1962 when Wolfe opened Esquire on his desk in the Herald Tribune new room and beheld Gay Talese, star writer of the competing New York Times, writing a story about a real person as if he was a fictional character. But Talese’s role in inaugurating the New Journalism movement is never undervalued by Wolfe. Talese had the ability to transcend the confines of daily journalism and offer an original view of the world. For example:

New York is a city of things unnoticed…. [It] is a city for eccentrics and a center for odd bits of information. New Yorkers blink 28 times a minute, but 40 when tense. Most popcorn chewers at Yankee Stadium stop chewing momentarily just before the pitch. Gum chewers on Macy’s escalators stop chewing momentarily just before they get off – to concentrate on the last step. Coins, paper clips, ballpoint pens and little girls’ pocketbooks are found by workmen when they clean the sea lions’ pool at the Bronx Zoo.

Each day New Yorkers guzzle 460,000 gallons of beer, swallow 3.5 million pounds of meat and pull 21 miles of dental floss through their teeth. Every day in New York about 250 people die, 460 are born and 150,000 walk through the city wearing eyes of glass or plastic.

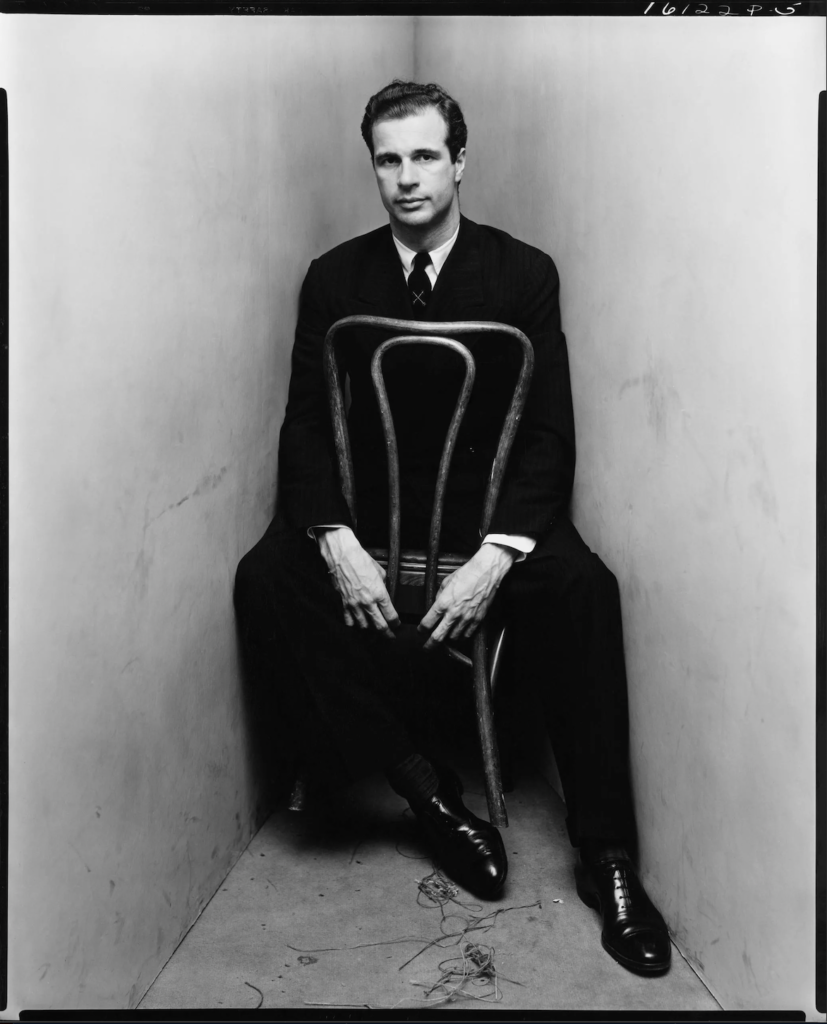

What Talese learned to do with the standard totem feature article was to adopt the mood and tone of fiction. He wrote nonfiction as if it was fiction. He advanced the story through a series of dramatic scenes, visualizing the piece as if it was comprised of characters of his creation whom he could move about on a fictional stage. But it was not fiction. In the Joe Louis article and is a number of stunning and innovative Esquire profiles of Joe DiMaggio, Frank Sinatra and others, Talese showed an ability for adopting the fictional structure, using the timing and pacing of a good short-story writer. Talese, like any journalist, was bound by a commitment to truth. He could gather all of the information he needed only through hours upon hours of observation.

Talese was a model. His meticulousness is legendary in the field of journalism. He was known for creating a file folder for each interview he conducted. Even if he interviewed the same subject several times, Talese created a folder for each session and included as much background – notes about weather, clothing, food consumed – so that he could later recreate the experience more fully. He also eschewed pens and notebooks and would not even consider a tape recorder. He trained his mind and produced stories so rich and detailed with regard to quotations that he was never challenged on the points of accuracy.

Talese’s Esquire profile “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” is perhaps the best example of the writer’s mastery of the New Journalism form. Talese accumulated more than 200 neatly typed pages of notes along with a $5,000 receipt for expenses.

The resulting article contained no interview with the singer, no one-on-one between Talese and the entertainer known as “the Voice.” Instead, Talese observed Sinatra as he tried to tape a television special while battling a cold, a disturbing set of circumstances for a singer. Readers learned more about Sinatra from the scenes related by Talese than they would have through any extensive exchange of questions-and-answers. Talese made no judgments about the singer. He merely showed Sinatra, annoyed with his infirm voice, as he bullied those around him.

Talese spent much of the 1960s crafting the magazine articles that embodied the best of New Journalism, and he later came to decry the decline in the quality of magazine journalism after he and Wolfe and the others began concentrating on longer projects. In Talese’s case, he began studying American institutions – the New York Times in The Kingdom and the Power, the Mafia in Honor Thy Father, the sex industry in Thy Neighbor’s Wife – and withdrew from the world of magazine writing.

Yet it was Talese who inspired the great rush toward New Journalism in the early 1960s. Wolfe said Talese’s Esquire articles were “so much better than what he was doing (or was allowed to do) for the Times. Jimmy Breslin, Wolfe’s colleague at the Herald Tribune, was another writer experimenting with the techniques of fiction in the form of journalism. Breslin had labored facelessly in the vineyards of magazine freelancing until his book about the New York Mets’ disastrous first season, Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?, caught the eye of Herald Tribune publisher Jock Whitney. Whitney wanted to offset the “snoremongers” (Wolfe’s term) on his newspaper’s editorial page with a column that was more lively and loosely defined. In that era, the newspaper columnist was a character like Arthur Krock of the Times or Walter Lippmann of the Herald Tribune, who — in Wolfe’s view — stepped back from the reporting that had given them stature and mulled over the reporting of other reporters and decided “what it all meant.”

These sorts of columns made editorial pages the very essence of a “vast wasteland.”

Breslin’s column was different. It dealt, more often than not, with a news event. He worked with the city editor to find what sorts of assignments were on the budget for reporters and then he would go along with that reporter — to the police station, the courthouse, the mayor’s office or wherever else the news was happening. Back at the office, the reporter would write a totem account of the event and Breslin would write one of his columns. These columns often employed the techniques that Talese used on a larger scale in his Esquire pieces: Breslin often started with a scene and allowed the dialogue to reveal character. In the space of a 500-600 word column, Breslin could speak volumes. The editors realized this brilliance could easily be lost on the editorial pages, so Breslin’s column often started on the front page.

Talese’s experiments and the proximity of great talents such as Breslin and other Herald Tribune writers (Dick Schaap and Charles Portis among them) in the same newsroom inspired Wolfe to plunge into the game of being the best feature writer in town. Wolfe’s frenetic style attracted a level of resentment that Talese and Breslin appeared to be immune from. Although Talese’s writing rarely contained the sorts of verbal gymanstics Wolfe used as a matter of course, it was the amount of detail and the rabid accumulation of raw material that set his work above that of the typical magazine writer. He was well beyond the conventions of journalism.

Of course, Wolfe drew the ire of the literary establishment largely because of the controversial New Yorker articles, but also because of his strong, nearly baiting statements about the New Journalism. “I had the feeling,” he wrote, “that I was doing something that no one had ever done before in journalism.”