Doing Time on the Proud Highway

Appeared in Hunter S. Thompson, a critical biography (Twayne, 1991)

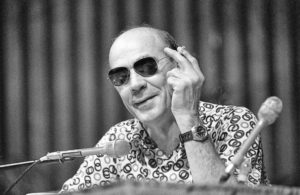

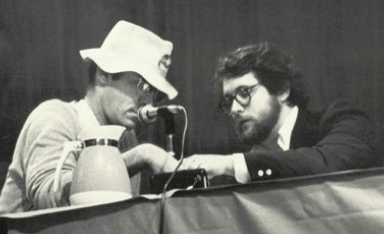

I interviewed Hunter Thompson twice – in April 1978, onstage at Western Kentucky University, and again in March 1990, when I was in the agonies of completing my first book on him. That second interview follows.

Thompson used portions of his answers to my questions in Songs of the Doomed (Summit Books, 1990) and reprinted a larger part of the interview in Kingdom of Fear (Simon and Schuster, 2003). The complete interview appeared in my book and also in Conversations with Hunter S. Thompson, edited by Beef Torrey and Kevin Simonson (University Press of Mississippi, 2008).

I’ve edited the interview slightly to make it more readable, and tweaked a couple of my questions in the name of clarity but no words have been changed. My questions are in boldface, and Thompson’s answers are in regular type.

………

Your North American articles for the National Observer in 1963 seem so much more sedate than your dispatches from South America in 1962 and early 1963.

When I came back from South America to the National Observer, I came as a man who’d been a star — off the plane, all the editors met me and treated me as such. There I was, wild and drunk in fatigues and a Panama hat. I said I wouldn’t work in Washington. The National Observer is a Dow Jones company so I continued to write good stories, just without political context. I drifted west.

Were there problems in dealing with the Observer when you were closer to the editors?

The National Observer became my road gig out of San Francisco. I was too much for them. I would wander in [to the Dow Jones bureau] on off hours, drunk and obviously on drugs, asking for my messages. Essentially, they were working for me.

They liked me, but I was the bull in the china shop – the more I wrote about politics the more they realized who they had on their hands. They knew I wouldn’t change and neither would they.

Berkeley, Hell’s Angels, Kesey, blacks, hippies . . . I had these connections. Rock and roll. I was a crossroads for everything, and they weren’t making use of it. I was withdrawn from my news position and began writing book reviews – mainly for money. The final blow was the [Tom] Wolfe review.

I wrote this strongly positive review of Wolfe’s Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby. The feature editor killed it because of a grudge. I took the Observer’s letter and a copy of the review, with a brutal letter about it, all to Wolfe. I then copied that letter [to Wolfe] and sent it to the Observer. I had told Wolfe that the review had been killed for bitchy, personal reasons. I left to write Hell’s Angels in 1965.

What was the nature of the conflict with the Observer over the coverage of the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley?

The Free Speech Movement was virtually nonexistent at the time, but I saw it coming. There was a great rumbling – you could feel it everywhere. It was wild, but Dow Jones was just too far away. I wanted to cover the Free Speech Movement, but they didn’t want me to.

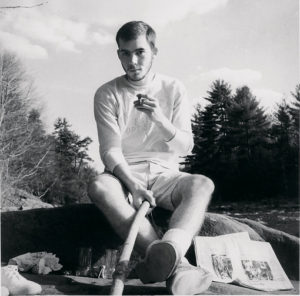

Earlier, you’d spent some of your time at Time, Inc., retyping the works of Faulkner, Fitzgerald, and other great writers in an effort to understand their style.

I would type things. I’m very much into rhythm – writing in a musical sense. I like gibberish, if it sings.

Every author is different – short sentences, long, no commas, many commas. It helps a lot to understand what you’re doing. You’re writing, and so were they. It won’t fit often – that is your hands don’t want to do their words – but you’re learning.

What writers have had the greatest influence on you?

Conrad, Hemingway, Twain, Faulkner, Fitzgerald . . . Mailer, Kerouac in the political sense – they were allies. Dos Passos. Henry Miller, Isak Dinesen, Edmund Wilson, Thomas Jefferson.

Did writing sports have an effect on your writing?

Huge. Look at the action verbs and the freedom to make up words – as a sports editor, you’ll have twenty-·two headlines and not that many appropriate words. At the Air Force base [he was sports editor of the Command Courier at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida in the late Fifties], I’d have my section: flogs, bashes, edges, nips, whips – after a while you run out of available words. You really get those action verbs flowing.

I’m curious, because some of the best American writers – Lardner, Hemingway, even Updike – covered sports in one way or another.

I put it all together once with my farewell to sports writing, but I always come back to it under odd circumstances: Ali, the Kentucky Derby, even the Mint 400.

What caused the rift with Rolling Stone? Was it something that was building for a while?

Wenner folded Straight Arrow Books shortly before the Saigon piece [Thompson’s 1975 assignment to cover the end of the Vietnam War]. I had to write that piece because the war had been such a player in my life for 10 years. I needed to see the end of it and be a part of it somehow.

Wenner folded Straight Arrow at a time when they owed me $75,000. I was enraged to find that out. It had been an advance for [The Great] Shark Hunt. I wrote a seriously vicious letter – finally saying all I was thinking as I was taking off for Saigon.

While in Saigon, I found I’d been fired when Wenner flew into a rage upon receiving the letter. Getting fired didn’t mean much to me. I was in Saigon, I was writing – except that I lost health insurance. Here I was in a war zone, and no health insurance.

So, essentially, I refused to write anything once I found out. I found out when I tried to use my Telex card and it was refused. I called to find out why. I talked to [managing editor] Paul Scanlon, who was sitting in for Wenner [who was] off skiing. He told me I was fired, but fixed my Telex card.

The business department had ignored the memo to fire me because it’d happened too many times before. They didn’t want to be bothered with the paperwork, so Wenner’s attempt had been derailed.

Anyone who would fire a correspondent on his way to disaster . . . . I vowed not to work for them. It was the end of our working relationship, except for special circumstances.

About that time, they moved to New York. Rolling Stone began to be run by the advertising and business departments and not by the editorial department. It was a financial leap forward for Wenner and Rolling Stone, but the editorial department lost any real importance.

You shouldn’t work someone who would fire you en route to a war zone.

I got off the plane [in Saigon] greeted by a huge sign that said, “Anyone caught with more than $100 U.S. currency will go immediately to prison.” Imagine how I felt, with $30,000 taped to my body. I was a pigeon to carry the Newsweek payroll and communication to those in Saigon. I thought we’d all be executed. It was total curfew when we got off the plane so we were herded into this small room with all these men holding machine guns. There I was, with three hundred times the maximum money allowance. We got out and leapt on a motor scooter and told the kid to run like hell. I told Loren [Jenkins, of Newsweek] I wouldn’t give him the money until he got me a suite in a hotel. Not an easy task, but he came through.

Was [the break with Rolling Stone] directly related to the “Great Leap of Faith” article [which editor Jann Wenner promoted as Thompson’s endorsement of Jimmy Carter for president in 1976]?

I had already picked up on Carter in ’74. It was a special assignment, as everything was after Saigon. I was still on the masthead: it was an honor roll of journalists, but the people on it – well, all of them were no longer with Rolling Stone. I didn’t like that they put on the cover that I endorsed Carter. I picked him as a gambler. Endorsing isn’t something a journalist should do.

Essentially, the fun factor had gone out of Rolling Stone. It was an outlaw magazine in California. In New York it became an establishment magazine and I have never worked well with people like that.

Today at Rolling Stone, there are rows and rows of white cubicles, each with its own computer. That’s how I began to hate computers. They represented all that was wrong with Rolling Stone. It became like an insurance office with people communicating cubicle to cubicle.

But my relationship had ended with the firing. The attempt was enough.

Your use of drugs is one of the more controversial things about you and your writing. Do you think your use of drugs has been exaggerated by the media?

Obviously, my drug use is exaggerated or I would be long since dead. I already outlived the most brutal abuser of our time – Neal Cassady. Me and William Burroughs are the only other ones left. We’re the only unrepentant public dope fiends around, and he’s seventy years old and claiming to be clean. But he hasn’t turned on drugs, like [Timothy] Leary.

How have drugs affected your perception of the world and/or your writing?

Drugs usually enhance or strengthen my perceptions and reactions, for good or ill. They’ve given me the resilience to withstand repeated shocks to my innocence gland. The brutal reality of politics alone would probably be intolerable without drugs. They’ve given me the strength to deal with those shocking realities guaranteed to shatter anyone’s beliefs in the higher idealistic shibboleths of our time and the “American Century.” Anyone who covers his beat for twenty years, and that beat is “The Death of the American Dream,” needs every goddamned crutch he can find.

Besides, I enjoy drugs. The only trouble they’ve given me is the people who try to keep me from using them. Res ipsa loquitur. I was, after all, a literary lion last year. [Referring to a 1989 honor from the New York Public Library.]

Does the media portrayal of you amuse, inflame, or bore you?

The media perception of me has always been pretty broad, as broad as the media itself. As a journalist, I somehow managed to break most of the rules and still succeed. It’s a hard thing for most of today’s journeyman journalists to understand, but only because they can’t do it. The smart ones understood immediately. The best people in journalism I’ve never had any quarrel with. I am a journalist and I’ve never met, as a group, any tribe I’d rather be a part of or that are more fun to be with – in spite of the various punks and sycophants of the press. I’m proud to be a part of the tribe.

It hasn’t helped a lot to be a savage comic-book character for the last fifteen years – a drunken screwball who should’ve been castrated a long time ago. The smart people in the media knew it was a weird exaggeration. The dumb ones took it seriously and warned their children to stay way from me at all costs. The really smart ones understood it was only a censored, kind of toned-down children’s-book version of the real thing.

Now we are being herded into the nineties, which looks like it is going to be a true generation of swine, a decade run by cops with no humor, with dead heroes, and diminished expectations, a decade that will go down in history as The Gray Area. At the end of the decade no one will be sure of anything except that you must obey the rules, sex will kill you, politicians lie, rain is poison, and the world is run by whores. These are terrible things to have to know in your life, even if you ‘re rich.

Since that’s become the mode, that sort of thinking has taken over the media as it has business and politics: “I’m going to turn you in, son – not only for your own good but because you were the bastard who turned me in last year.”

This vilification by Nazi elements within the media has not only given me a fierce joy to continue my work – more and more alone out here, as darkness falls on the barricades – but has also made me profoundly orgasmic, mysteriously rich, and constantly at war with those vengeful retro-fascist elements of the Establishment that have hounded me all my life. It has also made me wise, shrewd and crazy on a level that can only be known by those who have been there.

Some libraries classify Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas as a travelogue, some classify it as non-fiction, and some classify it as a novel. You refer to it as a failed experiment in gonzo journalism, yet many critics consider it a masterwork. How would you rate it?

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is a masterwork. However, true gonzo journalism, as I conceive it, shouldn’t be rewritten.

How would you characterize the book?

I would classify it, in Truman Capote’s words, as a non-fiction novel in that almost all of it was true or did happen. I warped a few things but it was a pretty accurate picture. It was an incredible feat of balance more than literature. That ‘s why I called it Fear and Loathing. It was a pretty pure experience that turned into a very pure piece of writing, It’s as good as The Great Gatsby and better than The Sun Also Rises.

I would classify it, in Truman Capote’s words, as a non-fiction novel in that almost all of it was true or did happen. I warped a few things but it was a pretty accurate picture. It was an incredible feat of balance more than literature. That ‘s why I called it Fear and Loathing. It was a pretty pure experience that turned into a very pure piece of writing, It’s as good as The Great Gatsby and better than The Sun Also Rises.

Your stint as a newspaper columnist [for the San Francisco Examiner] was successful, but do you have further ambitions within journalism?

I’ve never had any real ambition within journalism, but events and fate and my own sense of fun keep taking me back for money, political reasons, and because I’m a warrior.

Do you have an ambition to write fiction?

I’ve always had and still do have an ambition to write fiction.

For years your readers have heard about The Rum Diary. Are you working on it, or on any other novel?

The Rum Diary is currently under cannibalization and transmogrification into a very strange movie.

I am now working on my final statement — Polo is My Life, which is a finely muted saga of sex, treachery and violence in the nineties, which also solves the murder of John F. Kennedy.

I haven’t found a drug yet that can get you anywhere near as high as sitting at a desk writing, trying to imagine a story no matter how bizarre it is as much as going out and getting into the weirdness of reality and doing a little time on the Proud Highway.