The Taco Man

From Mile Marker Zero: The Moveable Feast of Key West

(Crown, 2011)

This is the first chapter of Mile Marker Zero, and it introduces Tom Corcoran, whose life intertwines with the book’s cast of characters — Jimmy Buffett, Tennessee Williams, Margot Kidder, Peter Fonda, Jim Harrison, Thomas McGuane, Elizabeth Ashley, Russell Chatham and the other artists featured in the book. Corcoran serves as the window for the narrative and here he illustrates the seductive power of Key West.

. . . . . . . . .

Tom, we had an active night tonight. I spent a lot of time talking with Buffett down at Nicholson’s house, and we both got very excited about the Key West years, the ‘missing years,’ the ones that you have so well documented. We’re going to reconvene down there and go back over the stories, the photographs, and maybe do a little boating. Let’s have ‘The Boys’ back – Chatham, McGuane, whoever’s alive. It’s going to be good. We’re going to have a little fun with this one.

Hunter S. Thompson, phone message for Tom Corcoran,

Christmas night, 2004

The open range, the open sea, the open sky, the open wounds of the heart, that’s where writers shine.

Thomas McGuane, Some Horses, 1999

I was in the face of a breaking wave in American culture. And I didn’t understand it, or really know what it was, but I knew something was going on, and I knew I was in the middle of it.

Thomas McGuane, interview, 1999

The best laid plans of mice and men go oft astray.

Robert Burns, “To a Mouse,” 1785

. . . . . . . . .

The plane banked, dipping its wing to make the turn and begin the approach, and that’s when Corcoran got his first good look at the island. Twice as long as wide, it was a bleached rock in the blue-and-emerald Caribbean. He saw neatly lined streets, an attempt to impose order on crushed shell and stone, but was struck by the relative absence of green. He hadn’t been sure what to expect, but he had assumed there would be trees, lush vegetation, palms and bananas and coconuts. It was Florida; it was the Tropics, for God’s sake. Yet as the plane descended, he saw himself being swallowed by a flat, blazingly bright, over-exposed world. He squinted as the plane came out of the blue and into the white.

This is it, he thought. Couple months here and I’m done.

He smiled, thinking about his post-college, post-Navy life. First . . . maybe graduate school, then maybe he’d settle down in elbow-patched glory as an English professor at some Midwestern liberal-arts college, writing small but important novels, embraced by wife, dog, 2.5 children, and throngs of adoring students. It would be a good, if unexciting, life.

Tom Corcoran was lucky. He was in the last year of his Navy stretch, and so far had avoided Vietnam. The war had not been center stage in America when he’d enlisted back in 1963, but to those who saw their student draft deferments slipping away with each low grade, Vietnam took on a newer, bolder role. After two disastrous years at Miami University of Ohio, Corcoran had decided to enlist, figuring he’d better beat the military at its own game. He could wait for the draft to take him and send him off in Army fatigues, or he could control his destiny. He wanted the Navy, the only logical choice for a boy from a Cleveland suburb. He also thought that if he was going to Vietnam, he might best serve his country from the relative safety of offshore. “If there was a war in the jungle,” he said, “I liked the idea of fighting the war from a steel bulkhead instead of hiding behind a bunch of leaves.”

He took a break from school in the summer of 1963, landing in San Diego, where he worked as a travel counselor by day and at night explored new frontiers of California bohemianism, soaking in the music and inebriants of the time. He figured this freedom was about to end, so he squeezed tight. He also figured his poor grades had sentenced him to the draft. So he skulked into the U.S. Navy Recruiting Office as if on the way to see the principal back at Shaker Heights High.

To his surprise, the officer behind the desk had some good news: Give us your summers and you can still go off and finish school, College Boy.

“What?” Corcoran asked.

“It’s your lucky day, Kid,” the recruiter said. “All you got to do is give us your summers. When you’re done with your degree, you’re ours for two years. You even get to come in as an officer.”

It was a revelation, a reprieve and a second chance for Corcoran to chase his dream of becoming a writer.

And so Corcoran returned to Oxford, Ohio, for the fall semester in 1963. His grades went through the roof. He spent his summers in the service, and by the time he graduated, he had aced Officer Candidate School and entered the real world as an officer and a gentleman.

Corcoran became expert in guiding drone helicopters that flew by remote control and fired torpedoes at imagined Russian submarines. They had those drones in Vietnam now, with spy cameras mounted on the hoods, using them as small, low-flying unmanned versions of U-2’s. But despite Corcoran’s skill – landing them easily on the pitching deck of the USS John Willis – he had still managed to avoid Vietnam.

So now it was late August 1968 and Corcoran was landing on six square miles of coral, on the downhill slide of his military career. Vietnam had taken more than 20,000 American lives. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated that spring. That very month, student demonstrators and reporters had been beaten – some nearly to death – by officers of the law in a police riot at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The world had gone insane. But Corcoran was untouched. He had become so expert with his drones that he was loaned out to other ships to teach his magic to new sailors. He was looking at ten more months of that duty, and then freedom.

The Navy wanted to wring all it could out of him, so he was being sent to this bleached rock for advanced courses in sonar. Though he had studied English literature and business and hoped to become a writer, he was also left-brain strong, which made him a natural in the worlds of sonar and radar. He was reassigned from the John Willis in order to run a 16-week training program. A natural teacher, his commanding officers figured he would be a good ripple in a pond. Give a man a fish; you have fed him for today. Teach a man to fish; and you have fed him for a lifetime. Corcoran was a good investment.

Corcoran didn’t care so much about sonar school. It was merely sixteen more weeks eaten out of his indenture to the Navy. After that, maybe graduate school. He didn’t really plan his life more than twenty-four hours in advance, and he was still flexible. Sometimes, he considered rediscovering his inner bohemian and getting back to California, and that hippie life he’d been reading about since he’d been wearing khakis. He’d don a new uniform of tie-dye and denim.

And then there was the decision about the women. He had yet to pick between the two girls he’d dated in college: Judy, the knockout who’d scored an ad-agency job in Boston right out of school, and Cornflake Susan, modeling in Manhattan. They called her Cornflake because the spray of freckles across her nose gave her a wholesomeness that Kellogg’s would kill to trademark. The body gave her something else, including a career as a fashion model.

Sixteen weeks, then a few months more on the Willis, and Corcoran was done. He’d worry about the women later. There were other women here, on this island, or so he’d been told. This was a plum assignment and the Navy ruled the little town. There had been a base here since 1823, and the locals were used to accommodating the officers and sailors, in all senses of the word.

He’d flown commercial all the way, but the last leg was on a sixteen-seat puddle jumper. He was the only military onboard. Most everyone else looked comfortable, despite the slight buffeting and the occasional sudden and unexplained drop. A tourist across the aisle blanched once, but Corcoran noticed that most of the passengers were blasé, probably locals coming back from a day trip to Miami.

As the plane descended, Corcoran saw the sun beginning its slow slide into the ocean. The airport was bordered by a canal on its left and Corcoran wondered if a poorly trained pilot ever over-corrected from the wide-banking turn and slid right into that open trench quarried out of the island’s rock. But this pilot was on mark. The landing gear dropped, the tires shrieked, the engines reversed – propelling the passengers forward – then the plane coasted, gloatingly, toward the terminal. As the pilot taxied up to the small, squat building, Corcoran gathered his belongings. The plane stopped at the gate, and he pulled himself out of his seat, towering over the other passengers in the aisle. Then they all marched, sheeplike, toward the open stairwell, down to the tarmac.

The blast of late-afternoon heat hit Corcoran’s face as if it had been thrown at him.

Sixteen weeks. He could do that, even if it was in a furnace. Sixteen weeks is four months closer to freedom, to grad school or hippiedom, to long hair, to solving the Judy–or-Cornflake dilemma.

Then again, there was that dream he had of being a writer and here he was, in this paradise with literary pedigree. And the Navy was paying him to be here. Yeah, he could do it. There were a lot worse things than being ordered to sixteen weeks in Key West.

* * * *

Originally Cayo Hueso (“island of bones”) when it was a Spanish city, Key West’s first white settlers found it littered with skeletons – from a battle or perhaps from a Calusa Indian burial ground. The name was anglicized into “Key West,” presumably because it is westernmost in the Florida Keys. Yet, for a brief period in its history, it was known as Thompson’s Island, a name chosen by Commodore Matthew Perry to honor Smith Thompson, the sixth secretary of the U.S. Navy. Perry had sailed into the harbor and claimed the rock for the United States in 1822. The following year, the Navy established a base, and ten years after that the Federal Army built Fort Zachary Taylor on the western edge. It was the southernmost military presence on United States soil.

Within a few years, Secretary Thompson was forgotten and Key West returned to its earlier name. By the middle of the 19th century, it was one of the country’s busiest ports. As the years passed, its proximity to Cuba, lax immigration laws and a friendly climate made it one of the centers of the cigar industry, which led to a boom in shipping.

The island’s literary history dates from that time. While the cigar workers diligently rolled tobacco, they listened to third-string actors read aloud. The Three Musketeers was a favorite. They loved Dumas, and Hugo. The cigar rollers, mostly Cuban, liked Spanish writers, but the reading of Shakespeare brought a reverent hush to the rolling room. It was entertainment and education. It helped the cigar workers learn the language and learn to get along in the English-speaking town.

The island remained a strategic port but was relatively isolated until developer Henry Flagler brought the railroad down the Keys from the mainland in 1912. He connected this westernmost key to Miami and the rest of his East Coast Railway. At the end of the line, he built the massive Casa Marina Hotel, which rose like a mirage from the green Caribbean at the south end of the island, the only shore with much of a beach.

But a devastating hurricane in 1935 wiped out much of the railway and killed hundreds, including nearly four-hundred veterans of the Great War who camped in the Keys, working on government construction projects. From the wreckage of the rail rose a new lifeline to the mainland. President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the construction of the Overseas Highway, a two-lane road piggybacking on the remaining track. It made for a long drive, but the trip to Key West was no longer the ordeal it had been in the days of island-hopping bridges and ferryboats. Soon it would be a destination for writers and artists hoping to work and play in this paradise.

Ernest Hemingway had come to town in the 1920s. Poet Robert Frost was there around the same time, and made nearly annual visits. Tennessee Williams moved down in the Forties and before long, the streets were thick with writers and wannabe writers.

Forty years later, the writers and artists and musicians were still coming. Seven years after Hemingway’s suicide, Tom Corcoran stood in front of The Old Island Inn, where Hemingway first stayed, back in the Twenties. Corcoran’s home was the room up front, overlooking Simonton Street. Years later, he would learn that he bunked in the same room as the Big Guy.

* * * *

Corcoran had lasted three days in Navy housing. There was a room shortage that summer and so the brass asked for volunteers to find apartments – the Navy would pay, of course – and ease the overcrowding in Bachelor Officer Quarters. Corcoran’s hand shot up. Sure, he said, I’ll be glad to move off-base.

“Suddenly,” he said, “I was living in Key West. And I just kind of fell into the mode. Nobody said, ‘You should get an apartment and buy a bicycle,’ but I did.”

And thus was his life derailed.

“I lived off-base but I didn’t mingle much with the townies at first,” Corcoran said. He didn’t find too many other officers to hang out with either. “In those days, if you were in a group of eight or nine or ten junior officers, you’d find there were some who were weasels. The weasel ratio was very high. A weasel was a guy who didn’t have a life and didn’t care and didn’t ever want one. No interest in anything, no sense of humor. There weren’t a lot of guys you’d want to have a beer with.”

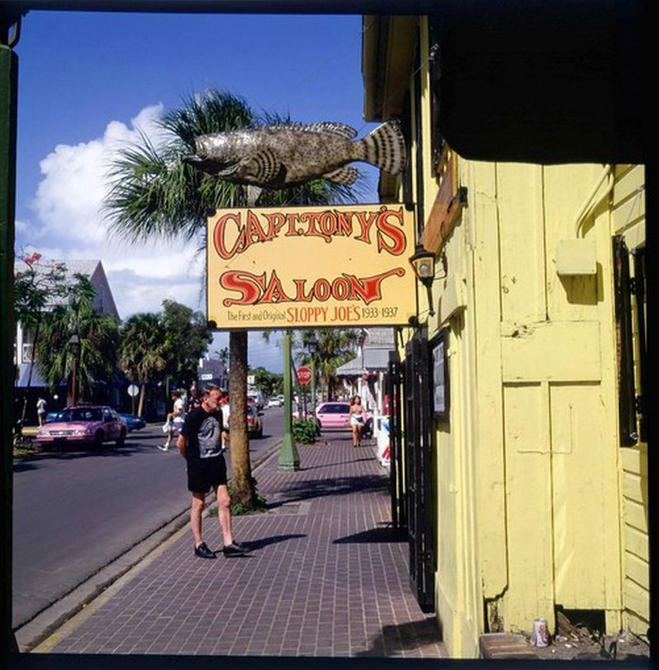

Lonesome for the women in his life, he figured it was easiest for Judy to come visit; Cornflake had high-demand photo shoots each week. So Judy came down for a month. They stayed in bed much of the time, but when they got up, they went to Captain Tony’s and tossed back a few. Corcoran found himself favoring Judy in the Judy-Cornflake war. Cornflake was a glamorous model, but her mother was an alcoholic and Corcoran believed genes influenced behavior. If he was going to share his life with one of these women, he wanted the one who wouldn’t turn out to be a drunk.

Soon, Judy had to return to Boston and Corcoran faced the last months of Navy life yawning before him. He found himself missing Judy, which struck him as extraordinary. He didn’t think he was ready to settle down yet. He was still unsure what post-Navy life would be like. These sixteen weeks on the bleached rock were altering his trajectory.

* * * *

Tom Corcoran was honorably discharged from the United States Navy at the end of September 1969. The world was still crazy. A half million longhaired kids had a mud fest in a farmer’s field near Woodstock in upstate New York, listening to three days of rock ’n’ roll. A return to Bohemian life seemed in order. Corcoran’s decommission had come at his home base in Newport, then he drifted back to Ohio to take stock and see old friends.

He hooked up with a college buddy named John Hilton. The two of them had met in 1964, working at the College Inn back in Oxford. Corcoran was just back from California and his Navy-recruiter revelation, dressed like a Beach Boy in huaraches, carrying a skateboard, and driving a beat-up old Dodge Dart decorated with Rat Fink decals. Hilton tended bar and Corcoran waited tables and took charge of the jukebox, stuffing it with house quarters when a gap between songs widened. “I had a pocketful of those things and I learned how to control a crowd,” he said.

Music helped Corcoran and Hilton bond. The house band at the College Inn was black, a venerable rhythm-and-blues outfit called Maurice and the Rockets. “Maurice looked like a car thief, like a wolf in a cartoon,” Corcoran recalled. “I don’t know that I ever knew rock’n’roll that was that pleasing ever again.”

Corcoran and Hilton shared a common goal during their college days: to “get fucked up for the least amount of money we could spend.” That was easy; at thirty-five cents a bottle, Budweiser was the premium beer. Schlitz on tap was a quarter.

They became close friends, but Hilton fell to the draft and Corcoran spun off into his Navy career.

Hilton had not escaped Vietnam, but he was back now and, like Corcoran, not sure what came next on his resume. They met up back in Ohio in the fall of 1969, pooled their money, and drove to Florida in Hilton’s Datsun 1600, ending up in Fort Lauderdale. They needed work, so they took construction jobs.

“By the time we got there, we were both broke and we dug ditches for beer money,” Corcoran said. They dug footers on a bridge site, lasted exactly one week by the watch, and lined up at payday and then turned their gaze south. “I got a paycheck and I said, ‘Well, that’s that career.’ ” Holding the money in front of Hilton’s face, he said, “I know where I want to drink this beer.”

They were caught in Captain Tony’s gravitational pull, managing to arrive at the bar a few weeks before the owner’s annual fishing vacation.

The little island had become the closest thing to home. Corcoran was a college graduate and a former Navy officer. But now, as he sat at the bar those afternoons, pissing away his money, he felt something else.

“Key West was peaceful, idyllic, tropical, and other-worldly,” he recalled. It also was sanctuary. “I wanted to shut out the mainland, the shitty mess that the Sixties had become. It was an alternative reality. And you could phone home from a pay booth and use American money.”

He decided to stay.

That first night at Captain Tony’s, a fellow sidled up at the bar and made conversation.

“Where you from?” he asked, nodding at Corcoran.

“Shaker Heights, Ohio.”

“Oh yeah? What’s your name?”

“Tom Corcoran.”

The guy’s eyebrows lifted. “You Marty Corcoran’s brother?”

Small-world-time. “Yep,” Corcoran said. “Marty’s my sister.”

The guy’s name was Mase Mason. Any brother of Marty’s was a friend of his.

They sealed their new friendship with a few more beers – on Mason – and Corcoran and Hilton marveled at how quickly you could make friends in paradise.

“Where are you guys staying?” Mason asked, after a bit.

Corcoran shrugged.

“Well, you can have my place,” Mason said, handing over the keys. “It’s the Fogarty House, apartment two. I’m going shrimping. I’ll be gone a couple weeks.”

What great luck, Corcoran thought. He’d cleaned out his small savings account back home, sold his Navy uniform and sword, and was coasting on the fumes in his wallet.

“Matter of fact,” Mason mused over his beer. “You can have my girlfriend, too. Her name’s Lee.”

Mason went off shrimping, and although both Hilton and Corcoran liked Lee well enough, neither took up Mason’s offer. Within a couple of weeks, when Mason came back, Corcoran and Hilton had moved to a small apartment on Simonton Street, within sight of The Old Island Inn, where Corcoran’s Key West life had started . . . where Hemingway’s Key West life had started.

Corcoran had made a couple of decisions. First, “I wanted to be the next Hemingway. I thought all I needed was a hammock and a nice tall frosty. I was in the right place.” Second, it was Judy over Cornflakes. Cornflakes was being squired around Manhattan by New York magazine editor Clay Felker, attending parties with Tom Wolfe and Norman Mailer. She’d never go for the quiet life on the island. And that was part of the deal now. Corcoran knew that much.

As for Judy, those four weeks from the year before had grown in her memory. At work, she’d found herself imagining the island, wondering what a cold miserable winter day in Boston felt like down in the tropics. She had hoped she’d get this call one day. She quit her job and moved to Key West with no promises.

Corcoran worked construction again, this time on the Navy base. It helped him pay the rent on this new apartment he got with Judy, over on Grinnell Street, near the Overseas Food Market.

Eventually, they drifted away from Hilton and became an insular couple. They had nodding friends, and there was Captain Tony’s, of course, but it was intense make-love-until-our-strength-is-gone time. They shut out most everyone else.

After a few weeks, Judy was pregnant. Corcoran was happy, but neither of them considered marriage. That was so Mainland.

As Corcoran would soon learn, living in Key West was different. The community was attracting a lot of other young people who were dissatisfied with the country and its status quo. Some came because they disillusioned, heartbroken or world-weary. Key West was a hideaway for some.

But there were also those who saw Key West as the place to experiment with their lives or their art. The lure of a no-holds-barred society on a rock in the blue water of the Caribbean was intoxicating, and so an extraordinary group of young people began the journey down Highway 1. When Tom Corcoran made the decision to stay in Key West, had no idea that a decade later, he would still be there, having befriended and collaborated some of the greatest artists of his generation.

* * * *

A postcard afternoon, one of those first weeks in 1970, still inhaling the aroma of the Sixties . . . .

Tom Corcoran sits on a barstool in Captain Tony’s. This is where Hemingway used to drink. It’s the original Sloppy Joe’s. That place across Duval that calls itself Sloppy’s . . . sure, it markets itself as Papa’s favorite bar, but the locals know Captain Tony’s has the vibe and the history.

Corcoran sits there, drinking this beer, when a hippie rides up on a three-wheeled bicycle. He’s a white guy but they call him Afro because of the mushroom cloud of hair that encircles his head. Corcoran gets off the stool, walks outside, and checks out Afro’s bike. In the basket are tacos, sauce, a bottle of soda, a handful of napkins. He’s seen Afro riding around on the thing, not sure what the deal was.

Afro’s just looking at him.

“I want your job,” Corcoran says suddenly.

Afro shakes his huge, hairy head. No way. He’s the Taco Man; he is The Shit on those languid afternoons in Key West when people get the munchies.

Corcoran doesn’t want to let go of this fantasy, no matter how small or fleeting. “If you ever get tired of your job,” he says, “I want it.”

“Sure, man,” Afro says. Then he gets on the bike and pedals away.

“Tacos! Right here, get your tacos!” They come from a place a couple blocks away, a place called Pancho’s.

Two days later, same time of day, same barstool: Corcoran’s sitting there, putting a beer in intensive care when he hears this horrible clattering noise.

He turns around and Afro is riding the three-wheeled bike into Captain Tony’s, right through the front door.

He gets off the bike and starts to walk away, nodding at Corcoran. “It’s all yours, man.”