Jerry Jeff Brings Jimmy to Key West

From Mile Marker Zero (Crown, 2011)

Copyright © 2020 William McKeen

‘Murphy’ is the name assigned to a key character in Mile Marker Zero. She is a young woman who played a critical role in the Key West arts community of the 1970s. At this point in the book, she has already become intoxicated by the southernmost city and, with Jerry Jeff Walker, brings young Jimmy Buffett face-to-face with the town that would become his muse.

* * * *

Florida was that reservoir tip at the eastern edge of the country and people came floating down from Provincetown, from Ohio, from way up North, even from Miami.

And somewhere along the way, Murphy met Jerry Jeff Walker.

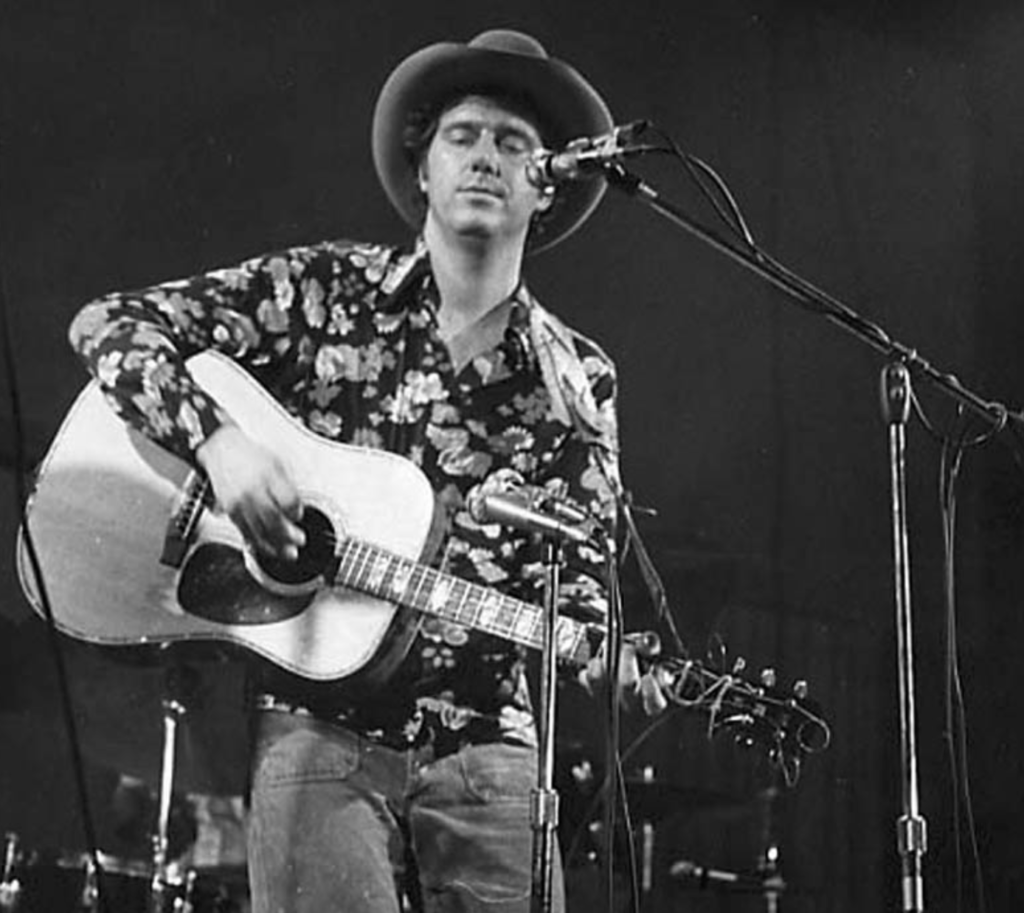

Jerry Jeff Walker was the perfect name for a country-folk-bar singer. It was perfect because it was made up after he read the job description for Sixties Singer-Songwriter.

He was Ronald Clyde Crosby and he was born in upstate New York during the early days of the Second World War. By the time he hit his teens, he was in the throes of Elvis love, like most everyone else in his generation. Elvis got girls, so Ronald Clyde Crosby wanted to be like Elvis. He learned to play the guitar and soon was in The Tones, a rock’n’roll band in Oneonta, New York. Dreams of stardom foundered. The Tones didn’t pass the audition for “American Bandstand.” A recording deal put professional musicians in the studio as The Tones, cutting Crosby out of making a record. He joined – and soon left – the National Guard and drifted down to New Orleans, where he played for change on street corners.

“Ronald Clyde Crosby” wasn’t filling the halls as a stage name, so he came up with the “Jerry Jeff Walker” persona and things soon began to turn around.

Jailed for drunkenness in New Orleans, he shared a cell with an old tap dancer he soon immortalized in his song “Mr. Bojangles.” He earned a recording contract with Vanguard, a safe haven for renegade folk musicians, but he recorded “Mr. Bojangles” for Atco, a revered independent rock and soul label, and he had a modest hit. Recorded two years later by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, the song sold a million copies. Then it was fair game for every singer on earth to have a whack at it and most of them did, from Neil Diamond to Bob Dylan to Sammy Davis, Jr.

So Walker was now living the life and one night that life took him to South Florida. There was a modest and interesting folk music scene there, presided over by Fred Neil. Neil was one of music’s great what-might-have-beens. He always bubbled under the surface and never achieved fame as a performer, though his songs were much admired and recorded. Around the same time the Dirt Band had a hit with “Mr. Bojangles,” the singer Nilsson had a million seller with Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’,” used as the theme in the film “Midnight Cowboy.”

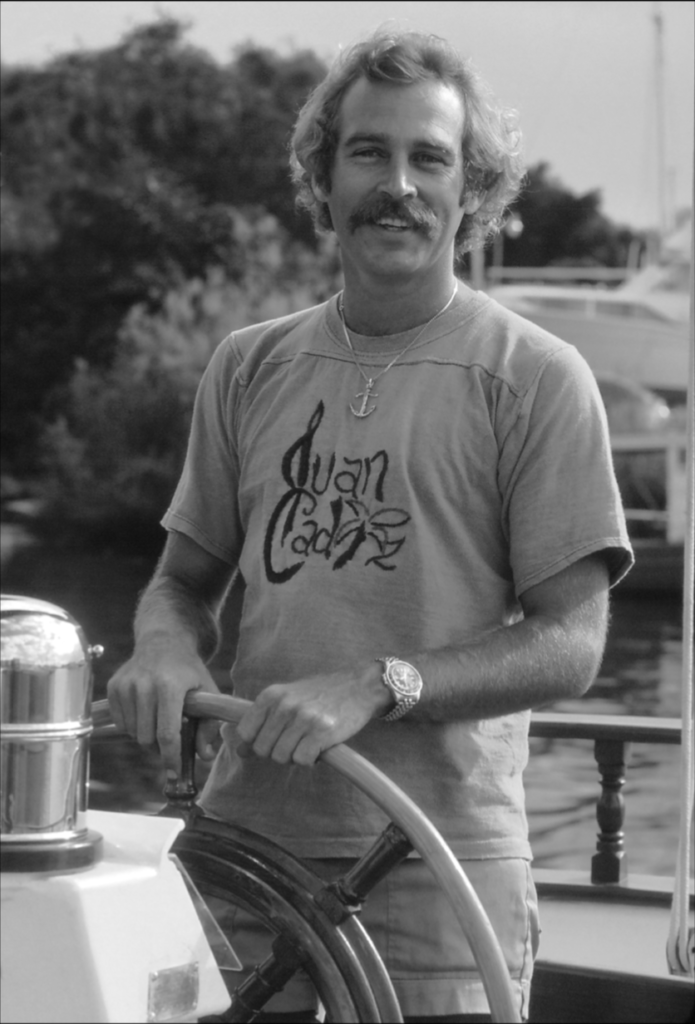

At that moment, Florida was perfect for Neil and for Jerry Jeff. It was a good, warm-weather place to gig. And on a swing through Key West, Jerry Jeff Walker met Murphy.

“He had just recorded a live album in Coconut Grove,” she recalled, “and he moved to Summerland Key. He’d just broken up with his wife.”

Summerland was just 30 miles up U.S. 1, easy driving distance from Key West, even with a snootful. He met Murphy and before long, they were together.

“I got in trouble,” Murphy said, “and I had to go home and have a baby.”

Walker settled with Murphy and now the baby boy, Justin, in Coconut Grove, to be near Miami’s one real folk club, the Flick. It was a regular gig for Walker. He still traveled the folk circuit, sometimes taking Murphy with him (mom or friends watched the baby), but he always returned home to Coconut Grove.

Nashville was as inevitable as the clap for a folk or country musician in that era. It was still the Old Nashville, with wavy toupees and Nudie suits and the Grand Old Opry at the Ryman Auditorium. Folk singers and younger country performers were looked down upon as grubby hippies, though that was beginning to change. Bob Dylan, furry-headed symbol of American Youth, had been recording in Nashville for half a decade. Some of the studio musicians, the “Nashville Cats,” as they were known, began growing their hair. Though things were changing, Nashville was still seen by younger musicians as unavoidable and inevitable.

Walker was in Nashville, kissing rings and paying dues, when his music-publishing rep said he wanted to take him out on the town, for wine and dine. The rep brought along another one of his clients, a young kid with the worst luck in the world.

Walker and the kid hit it off. The kid looked up to Walker – by God, he’d had a hit song – and they spent most of the night drinking and talking, losing the publishing rep somewhere along the way. Walker saw to it that the kid got back to his home, a somewhat primitive little cabin on the west end of Nashville. Walker told the kid to look him up sometime “whenever you’re in the mood to come to Coconut Grove.”

The kid went inside the cabin, trying like hell to not wake his wife, because it was nearly dawn and that would be reason No. 4,032 to leave him. So he stood there in the laundry room of his rickety cabin, looking down as this matched avocado washer and dryer and wondered what in the hell he had done to deserve this life. He’d finished college and even tried his hand as a journalist, writing for Billboard magazine. But he wanted to be a performer, he wanted to be a singer and songwriter like Jerry Jeff Walker and live in a place with a name like Coconut Grove, instead of here in Nashville with the avocado appliances and a woman in the next room who hated the air he fucking breathed.

Face it, he thought to himself. You’re a failure.

And that’s when Jimmy Buffett decided to make a change in his life.

* * * *

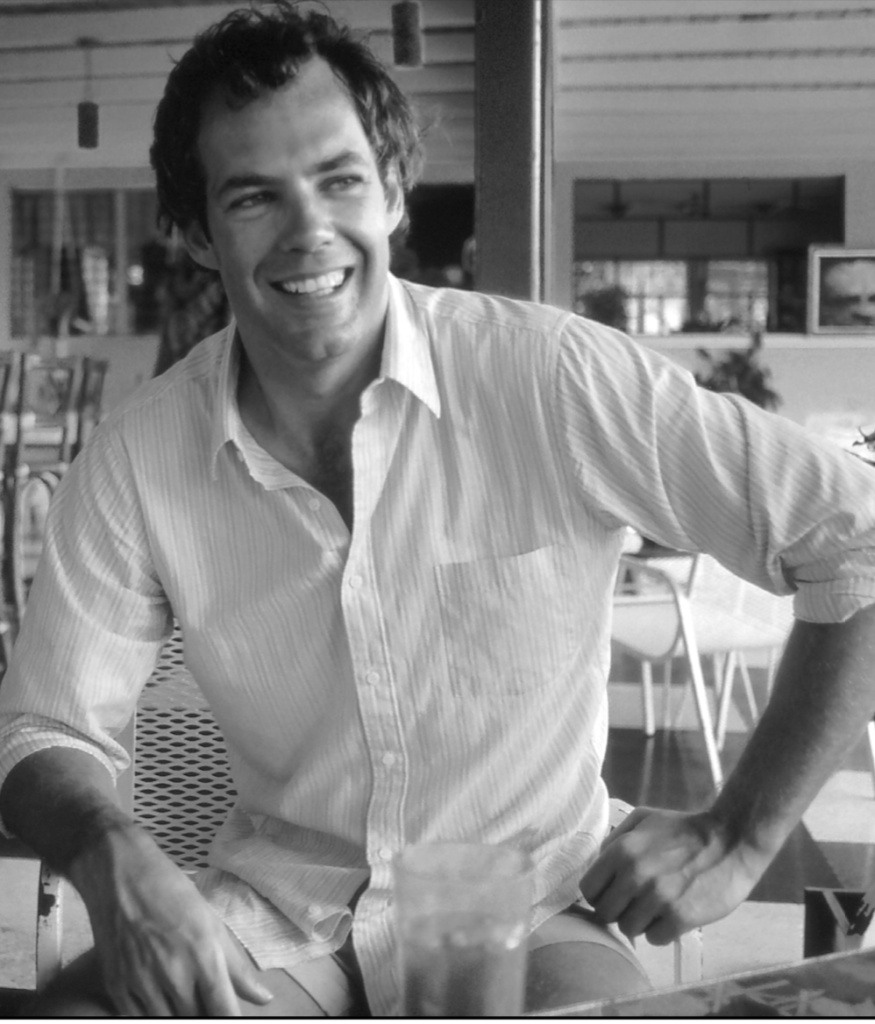

James William Buffett was born in Pascagoula, Mississippi, on Christmas Day 1946. He grew up in Mobile, Alabama, served as an altar boy, and attended Catholic school. He went to Pearl River Community College before transferring to Auburn University and finally graduating from the University of Southern Mississippi, where he earned a degree in journalism. But he had something other than newspaper work on his mind.

“I started out wanting to be a Serious Southern Writer,” he wrote. “My mother had made me a reader and stressed the legacy of my family’s Mississippi roots. William Faulkner, Walker Percy, Eudora Welty, and Flannery O’Connor were household names – Mississippians who had made people take notice.” He was off a bit on O’Connor’s geography – she was born in Savannah, Georgia – but he was raised with a reverence for the great southern writers and an appreciation for the power of language used well.

He began playing guitar while in college and performed at coffee houses. He played for change on New Orleans street corners. “I was in college at the time, a freshman at Auburn University,” he said. “I was a shy, awkward kid from Mobile, kind of a wallflower. My roommate had a guitar, and even though he knew only three chords, he always he always seemed to be the center of attention with women. I said, ‘Teach me those chords.’ So I learned the guitar and started hanging around folk clubs, watching the bands. . . . and the women – all the time, women – were hanging out with the band. I thought, ‘This is the job for me.’”

He decided that music was a quicker path to getting laid than literature, so he headed for Nashville, the closest music mecca. “The only reason I went to Nashville was because I didn’t have the money to buy enough gas to get to L.A.,” he said. Because of his background in journalism, he was able to get a job with Billboard, the bible of the music industry. Though the magazine was headquartered in Los Angeles, it had significant bureaus in New York and Nashville. Buffett turned out to be a pretty good reporter and in his short career reported one considerable scoop. He broke the story of the breakup of the celebrated bluegrass duo, Flatt and Scruggs.

But being on the periphery of the music business was not enough to satisfy him. “I got into music basically to meet girls,” he said. “It looked like the greatest job in the world.”

He lucked out, getting a foot in the door not long after his arrival. His career as a recording artist seemed off to a good start when he secured a deal with Barnaby Records, an independent label owned by smooth-voiced and well-sweatered singer Andy Williams. The label rose from the demise of Cadence Records, which had been successful as the first home of the Every Brothers in rock’n’roll’s golden era. Williams took the assets of Cadence and established Barnaby with the reissued recordings by the Everlys, then in vogue with the late Sixties rock’n’roll revival. Barnaby began looking for new talent and scored with novelty singer Ray Stevens’ serious ballads, “Mr. Businessman” and “Everything is Beautiful.” Williams signed his then-wife, French chanteuse Claudine Longet, to a contract. Buffett was one result of the label’s search for new talent.

He signed with Barnaby in 1970 and was pitched by the company as a country-and-western entertainer. It was the middle of rock’n’roll’s first real exploration of its country-music roots. Two years before, the most important player in popular music, Bob Dylan, had begun recording country-tinged albums in Nashville. Dylan’s former backing band emerged from his shadow and, known simply as The Band, had recorded two influential albums that drew on the roots of country music. The Band was even featured on the cover of Time magazine as “The New Sound of Country Rock.” A bonafide rock band. The Byrds, switched directions, played country music and soon spawned the full-tilt county band, the Flying Burrito Brothers. Soon, Good Old Boys were springing up everywhere as cosmic cowboys and Times Square shitkickers.

So it made sense for Barnaby Records to position its newest artist as the latest Nashville longhair. With his drooping desperado moustache, Buffett even looked the part. The music industry geniuses at Barnaby agreed that Buffett was perfectly cast.

Buffett disagreed. “They assume if you come from Alabama, you listen to country music,” he said. “I didn’t really like it much. All my early influences were out of New Orleans. . . . So it was a gumbo type of musical experience. I’d listen to the radio from New Orleans – Benny Spellman, Irma Thomas and great old black New Orleans artists.

But country was hot, Buffett was white and it was Nashville. Barnaby teamed him with a novice producer Travis Turk – who would follow another path to a long and successful career as a voice actor – to create the album, Down to Earth. Buffett wrote all of the songs (two in collaboration), but they were not standard country fare. The lead track, a song called “The Christian?” was an indictment of hypocrisy. Johnny Cash could get away with songs like that, but not an unknown kid from Alabama. The cover showed Buffett looking out the window of a car, half buried in the mud by the Cumberland River. He looked miserable.

The album went nowhere. It sold 324 copies on its release. Three singles were issued, but they all died on the vine. “The Christian?” upset some of the country disk jockeys and they made it clear they weren’t really interested in hearing anymore from Jimmy Buffett. Still, Buffett supported the album by playing the usual gigs on college campuses and at coffee houses and folk-music clubs. “It was a bad time,” he recalled. “Yelling at the college kids to shut up so I could hear myself play.” He’d wished to be successful overnight, but didn’t really expect it. So he stayed on the circuit and he and Turk began moving toward making another album.

The second effort, High Cumberland Jubilee, was recorded in 1971 but was not released for several years. Barnaby Records claimed the master tapes had been lost, but there was grumbling from Buffett that “lost master tapes” really meant “your album stiffed and we want to bury you.”

One of the girls who had liked Buffett’s guitar playing was Margie Washicheck, and they had married in 1969, moments before his expected stardom. Now it was 1971 and the High Cumberland tapes were lost and Jimmy Buffett was in the laundry room of his cabin and Margie was sleeping a couple of rooms away, dreaming about how unhappy she was in her marriage. And that was when Jimmy Buffett had his Jerry Jeff Walker epiphany.

Buffett had been playing the usual assortment of clubs in throughout the South, but had never gotten the most-desired booking on the circuit: The Flick in Miami. Everyone wanted to play the Flick, mostly because of the weather. Artists lined up asshole-to-bellybutton for a chance at a January or February booking there. But it was a significant venue, weather aside. It regularly drew Joni Mitchell, Fred Neil, John Sebastian and other established artists.

Buffett was popular with the club owners in St. Augustine, Florida, and Athens, Georgia, and the other stops on his never-ending tour. He asked all of them to call Warren Dirken and put in the good word for Jimmy Buffett. Dirken was the persnickety owner of the Flick and he didn’t return a lot of phone calls. But finally, owning to Buffett’s persistence, Dirken gave in and offered to put Buffett on the bill.

Buffett called Walker immediately. “Sure, man,” Walker said, confirming that the offer was still good for a free place to stay in Coconut Grove.

“I was flat broke at the time,” Buffett recalled, “and left the Mercedes with Margie. I had bought it as a status symbol and then couldn’t afford to fill it up with gas. It was the only thing of any value that we had, and she deserved it for putting up with my rather shallow and immature attempt at being a husband.”

During his Billboard days, the magazine had given Buffett a company Diner’s Club card. It was long since expired, but Buffett held it up to the cute girl at the TWA ticket counter at Nashville International Airport. His thumb covered the car’s expiration date, as she typed the numbers into the system for a one-way ticket to Miami, He had the grin and the charm hitting her in the face full blast, hoping she wouldn’t ask him to move his thumb. It was a rainy and miserably cold day in late October 1971 when Buffett got on the 727 headed south.

* * * *

Jerry Jeff Walker was waiting for him at Miami International. After the back slaps and how-are-yous, Walker drove him to Coconut Grove in his candy-apple red 1947 Packard sedan with “Flying Lady” on the car’s front vanity plate.

To Buffett, Miami was paradise. He’d left behind cold drizzle, a failed marriage and a career going nowhere. Here, at least there was sunshine, good weather and Jerry Jeff, who seemed incapable of unhappiness. At home, Buffett met Murphy and the baby, and got settled to his room at the back of the house. That afternoon, he sat in a lawn chair and beheld the beauty of tropical Florida.

“I was sitting under a cluster of royal palms with a breeze coming off of Biscayne Bay,” he recalled. “I was barefoot, in shorts and a T-shirt, eating lobster salad and drinking ice-cold beer, laughing and listening to Murphy’s stories of Key West.”

Buffett showed up at the Flick the next day, surprised to find it in a non-descript strip mall. It was well before the place opened. He brought his guitar, planned to introduce himself to owner Warren Dirken, and check out the setup for that night’s show.

Dirken was unimpressed with the scruffy kid. He was arguing with a produce seller and made Buffett cool his heels. Finally, he told Buffett he was two weeks early for his booking. Are you sure? Buffett asked. Dirken glared. “Bullett, you open in two weeks. See you then.” Buffett knew this was the right day, but swallowed the correction. No reason to piss off the owner of the most coveted gig on the circuit. OK, Mr. Dirken, he said. See you in two weeks.

So he slunk back to Casa Jerry Jeff and told his sad story. The host shrugged. “Asshole club owners” was all the said. Buffett was wondering what he would do with himself for the next two weeks. He didn’t want to outstay his welcome.

It was the irrepressible Murphy who had the aha moment that altered the trajectory of Jimmy Buffett’s life and the course of American popular music.

“Hell, Jerry Jeff,” she said, “Let’s go to Key West.”

In the interlude before the road trip, Buffett served as an assistant mechanic for Walker’s Flying Lady. Walker took the car into Hank & Bill’s Garage and Buffett earned his keep by helping to install a new fuel pump and a new carburetor. They had to order a brake drum and it didn’t arrive for a week, so finally they were ready for the trip down U.S. 1. With Jerry Jeff driving, Murphy riding shotgun and Buffett and baby Justin in back, they set off on a trip that would include a stop at all of the major bars in the Keys. Buffett let the little boy strum his guitar.

“This was Kerouac stuff, and I loved it,” Buffett said. He recalled his first trip to Key West as a “tropical Fellini movie.”

Off of Card Round Road – the route through Key Largo used by residents, not tourists – they stopped at Alabama Jack’s, an open-air seafood place barely a stone’s throw from the blacktop. Mosquito repellant required. Crab cakes, shrimp, cold beer, bullshitting with the locals, who were, by all accounts, crazier than shit. It beat the hell out of Nashville.

Then the trip continued as they merged back on Highway 1. They crossed the bulging bridge at Jewfish Creek and rolled into Islamorada. Buffett had made it that far once before, during a college Spring Break trip. South of Lower Matecumbe Key, on toward Marathon – all of that was virgin territory.

The water was mixture of emerald and blue and the sun made it shimmer. Buffett couldn’t take his eyes off of it. The sky was huge, with nothing to block it. The world was a thousand shades of blue and green.

Walker kept stopping, wanting to show off all of the bars, all the way south of Marathon and into Big Pine.

It’s a 155-mile drive from Coconut Grove to Key West, and even with two-lane traffic on U.S. 1, it’s usually three hours at most. That day, it took the Flying Lady eight hours to make the trip, mostly because of the stops to knock back a few. After Big Pine came No Name Key and the No Name Bar.

Finally, they hit town in time for the nightly spectacular.

“Let’s go right to sunset,” Murphy said excitedly. “Buffett has to see sunset!”

Buffett was perplexed. They were talking about “sunset” as if it was a place, not a thing that happened.

But when he got to Mallory Square and saw the crowds gathering for the nightly ritual, he understood. Sunbleached guitar strummers played some James Taylor, old rummies blew conch shells to call the sun home, hippies did the free-form arrhythmic Grateful Dead dance, and an old man on a bicycle sold homemade conch salad. It was a working pier of creosote and concrete, but every evening, people flocked there for the best view in town. They’d all watch for that moment when the sun slipped beneath the horizon with a green flash.

Buffett soaked up the spectacle. The last beers from No Name were wearing off, so Walker suggested they hit a new bar as soon as the sun slipped behind the Gulf of Mexico.

It was a short walk to The Chart Room.

Damn! It’s Jerry Jeff!

They got the standard greeting when they walked in the door. “Hey, boy – how are you?” Back slaps and hee haws.

“Hey, everybody,” Walker announced to the crowd. “This is my friend, Jimmy Buffett. This is his first time in Key West.”

Walker guided him to the bar, to introduce him to the bartender.

“Nice to meet you, Jimmy,” Tom Corcoran said, handing him a beer. “The first one’s free.”