Serendipity

Appeared in the Tampa Bay Times, March 26, 2006. Reprinted by the New York Times as part of its Times Education site.

There’s an art to finding something when you’re not looking for it.

In my freshman class, I require the 240 students to subscribe to the New York Times Monday through Friday. I haven’t even finished announcing this in class the first day, when the hands shoot up. “Can’t we just read it online?” they ask, the duh? implicit.

“No,” I say and the eyes roll. They think I’m some mossback who hasn’t embraced new media.

“Why not?” Challenging, surly, chips on the shoulders.

“Because then you would only find what you’re looking for.” Appropriately weird, elliptical, professor-like response.

I’m just doing my job: being baffling and obtuse, trying to make people think. By the end of the semester, I hope they get it. An online “front page” offers maybe a half-dozen stories and teasers for a few more – all in all, a poor substitute for the splendor of a good daily newspaper. Readers need someone to sift through the news and decide what’s significant enough to go on the front page. That’s how editors earn their big bucks. But it’s the other stories, the secret stash in the business section, the sports section or on the obituary page, that stop you and make you read.

How many people put “injustice,” “bigotry,” and “suffering” into search-engine windows? We don’t go looking for stories that anger us and make us want to change the world. But we find them when we turn the page. I wasn’t looking for it, but then I found it.

Nuance gives life its richness and value and context. If I tell students to read the business news and they try to plug into it online, they wouldn’t enjoy the discovery of turning the page and being surprised. They didn’t know they would be interested in the corporate culture of Southwest Airlines, for example. They just happened across that article. As a result, they learned something – through serendipity.

Serendipity is a historian’s best friend and the biggest part of the rush that is the daily magic of discovery. It’s one of those small things that make life worth living, despite all the torment, pain, tragedy and stifling Interstate traffic.

Serendipity is defined as the ability to make fortunate discoveries accidentally. There’s so much of modern life that makes it preferable to the vaunted good old days – better hygiene products and power steering leap to mind – but in these disposable days of now and the future, the concept of serendipity is endangered.

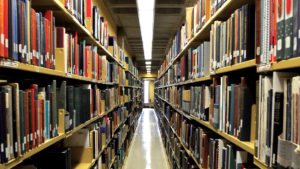

Think about the library. Do people browse anymore? We have become such a directed people. We can target what we want, thanks to the Internet. Put a couple of key words into a search engine and you find – with an irritating hit or miss here and there – exactly what you’re looking for. It’s efficient, but dull. You miss the time-consuming but enriching act of looking through shelves, of pulling down a book because the title interests you, or the binding. Inside, the book might be a loser, a waste of the effort and calories it took to remove it from its place and then return. Or it might be a dark chest of wonders, a life-changing first step into another world, something to lead your life down a path you didn’t know was there. Same thing goes with bookstores. We can shop online so easily, but there’s still the shipping thing for those of us who are impatient, and so a lot of bookstore traffic is made up of those who can’t wait for UPS. Or heck – maybe it’s the coffee. Those modern book supermarkets bring coffee and pastries into the equation, something Amazon.com hasn’t quite figured out how to duplicate, though I suspect they’re working on it.

It’s all about time. So many inventions save us time – whether it’s looking for information, shopping for clothes or checking what’s on television. Time is saved, but quality is lost. When you know what you want – or think you do – you lose the adventure of discovery, of finding something for yourself.

In another context, Thomas Paine once wrote: “The harder the conquest, the more glorious the triumph. ‘Tis dearness only that gives everything its value.” Too true, Tom! You may have been talking about the struggle for basic human rights and maybe I’m talking about sorting through the bargain table for boxer shorts that don’t ride up and instead finding socks with Stratocasters embroidered on the ankle, but we are on the same philosophical page.

Looking for something and being surprised by what you find – even if it’s not what you set out looking for – is one of life’s great pleasures, and so far no software exists that can duplicate that experience. (I get hectored a lot when I talk about this. But what about stumbleupon.com? That duplicates serendipity! Sure, Bud — once again, you’re allowing an algorithm to think for you instead of your own handsome melon.)

Technology undercuts serendipity. It makes it possible to direct our energies all in the name of saving time. Ironically, though, it seems that we are losing time – the meaningful time we once used to indulge ourselves in the related pleasures of search and discovery. We’re efficient, but empty.

Except for matters of life and death – and shopping at Wal-Mart – there’s an emptiness in finding something quickly. (We all want to minimize time in Wal-Mart, don’t we? Life is too short to spend too many of its precious moments in that particular hell.)

Serendipity has enriched my life intellectually and emotionally. It’s even stepped in and surprised me, giving my career new trajectories.

Years ago, when I was a part-time Ph.D. student, writing a historical dissertation on campus riots after the Kent State shootings, I was focusing on a particular antiwar demonstration at the University of Oklahoma. Interviewing my sources nearly 20 years after, I found some of their recollections sharp and others uncertain.

I was talking this over with a couple of friends when our conversation was interrupted by a rarely seen colleague who happened to drop into the lounge at that moment. “Say,” he said. “Excuse me for interrupting, but that riot you’re talking about – did anyone tell you that I filmed it?”

And indeed he had, as a young photojournalist. He gave me a copy of his film, and it confirmed those memories and gave me a sense of the scope of the event. (Modern historians are a lucky tribe. What if Edward Gibbon had a home video of Caesar’s assassination when he was writing The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire? Maybe it wouldn’t have taken him 12 years to finish the damn thing.)

Serendipity has continued to play a part in my work. A few years back, I got a publisher’s contract for a book, Highway 61, to be based on a long road trip I planned to make along the famous highway that runs from from the Canadian border to the French Quarter. I kept meaning to spend the months before the trip doing research, getting prepared, efficiently setting up interviews with people along the road. But life intervened. I was busy with work and falling in love. So when my grown son and I hit the road with no plan at all, I was terrified. What if nothing happened? What would I write about? We took our free-fall trip, following the path of the Mississippi River, and serendipity intervened. People walked up and introduced themselves, as if part of a cast of lunatics required in the telling of a good road story. And the plot also presented itself, quite by accident: a long-distance divorced father helping his son bid goodbye to childhood. We were both a little startled by the moments of truth we shared in the front seat.

We made another discovery on that trip. The world of music – a world so important to both of us – suffers from a lack of serendipity. My son is a member of the download generation, which finds its music online. I grew up in a world dominated by that great and subversive force of the 20th century: radio. Fifty years ago, when we were just beginning to cast off the elements of American apartheid, it was relatively easy for our society to enforce racial barriers – separate schools, separate stores, separate neighborhoods.

But the music that traveled in the air, via radio waves, did not observe Jim Crow boundaries. White kids, alone in their rooms, tuned their radios at night and heard the music of black America. Black kids found The Grand Ole Opry and learned for themselves about that old, weird America.

The result in my childhood was a serendipitous exposure to music that no amount of downloading can duplicate. As a kid, I’d turn on the radio and hear Frank Sinatra, followed by James Brown, followed by the Beatles, followed by the Supremes – and lots of other people. Music could astonish me. But now, with downloading, it has lost that ability. We miss the element of the chance encounter with musical genius. We have to be told of such genius or hear about it second-hand. One effect is that it’s balkanized the audience. We don’t have the sense of community. My older children, in their 20s, envy my generation. “We’ll never get to fall in love to the great music you had,” my oldest daughter once told me.

It’s an odd paradox. The audience today is larger and the choices are enormous – and yet more turns out to be less. We have hundreds of choices on television, but will we ever feel the moment of global community we felt staring at that box, watching a man named Armstrong walk upon the moon? Or will we ever, en masse, have a moment like that time the world met the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show? Will the world ever shed so many tears as we did watching the funeral of President Kennedy? We had three choices then and have 2,000 now. Likewise, in music: We are so formatted now that stations stratify the market, making it unlikely you will ever hear music you do not expect to hear.

The modern world is conspiring against serendipity. But we cannot blame technology. I’ve met this enemy, and it is us. We forget: We invented this stuff. We must lead technology, not allow technology to lead us. The world is a better and more cost-effective place because of technology, but we’ve lost the imperfections inherent in humanity – the things that make life a messy and majestic catastrophe.

We must allow ourselves to be surprised. We must relearn how to be human, to start again as we did as children – learning through awkward and bungling discovery. Otherwise, when it’s all over and we face the Distinguished Thing, we will have led extremely efficient but monstrously dull lives.

Some years back, Tom Wolfe came to my university and I hosted him for a week. I don’t drop his name merely for effect (though it’s only two syllables and shouldn’t hurt much). It’s just that I’ll never forget something he told me. On the last night of his visit, we found ourselves alone together at dinner, talking about our children. Though he’s 20 years older than me, we were at the same stage: ushering our children into adulthood. I told him that I didn’t really understand the profound depth of love until I became a father. And he said that he had married late (at 50) and had children soon after. He said, “And I think, ‘My God, I could have missed this.’ They opened up a door in my heart that I didn’t even know was there.”

And I realize that serendipity has also been lost in matters of the heart. Now, we plug a list of characteristics into a Web page in search of our True Love. We no longer allow for the chance encounter at the bookstore (we’re shopping online, remember?) or sitting next to someone new in church or simply looking into someone else’s eyes and feeling the eureka of discovery. We check off the qualities of this idealized other half, as if ordering from a Chinese menu. Matchmaking Web sites have replaced human conversation. (I tried the online thing once, and all I got in return was a stalker. She even wore camouflage.)

Not long after that conversation with Tom Wolfe, a door opened in my heart. I was living my dull, directed and orderly divorced-guy life and one day looked up and was struck by the thunderhammer of love. I wasn’t looking for her, but I found her. I had long since given up on the concept of remarriage. Yet, five years later, I am remarried and I am again waist-deep in the adventure of fatherhood. I now have a messy, aggravating and utterly inefficient life – and every day is a bouquet of surprises. I wake each morning, put on my socks and shoes, and face a new day of wonder and discovery. Why deny or refuse such a gift? If I had been looking for it, I would not have found it. It was serendipity, that ability to make fortunate discoveries accidentally, that opened that door in my heart.

And to think: I could have missed this.