Pandemonium With a Big Grin

This is another abandoned project. I intended to weave together the stories of the great literary journalists. Alas, this never took off. I couldn’t even think of a title for it. For a while, I called it Members of the Tribe, and later it was High Tide. Alas, another misfire.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Copyright © 2024 William McKeen

I’m brilliant, Newman thought, totally fucking brilliant!

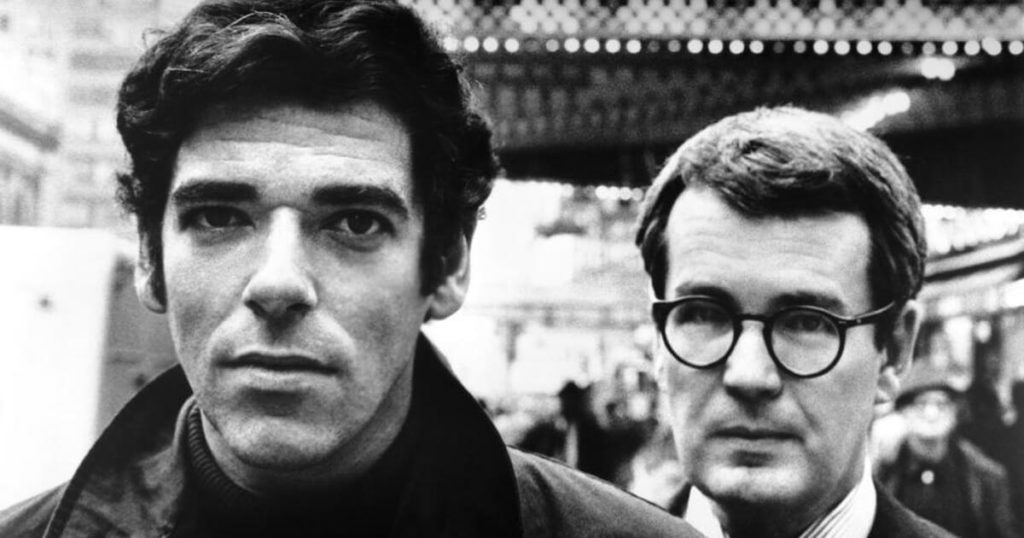

Inside his head: He’s the master of soft-core, the Tolstoy of the nymphet — Terry Fucking Southern — and he’s working for us now, and he’s fucking perfect for this story.

David Newman congratulated himself on his thundering intelligence. He was a down-masthead staff editor at Esquire, but still! — a semi-big deal he was, a concoctor of the magazine’s annual “Dubious Achievement Awards,” a writer in his own right, holder of screenwriter dreams (to be realized with Bonnie and Clyde), but right now, on this early summer day in 1962, he was pleased with himself — oh hell, let’s not undersell it, he was chortling — because news had just crossed his desk about an event that was perfect for the Terry Fucking Southern Treatment.

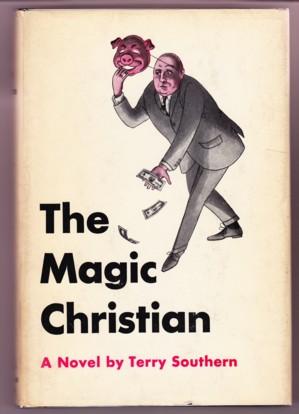

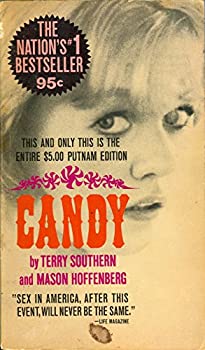

Southern was slumming, sort of. He was a big deal, author of two above-ground novels, Flash and Filigree and The Magic Christian, as well the recently outed co-author of the underground classic, Candy. That had been published under a pseudonym in 1958, but now everyone knew it was Terry Southern who wrote it, with a couple-chapter assist from his pal, Mason Hoffenberg, It was Terry’s work, no doubt about it.

Candy was published in Paris and banned in the Puritan America of the late Fifties. It had fans at both ends of the spectrum: literary types recognized it as brilliant porn parody, and chronic masturbators who saw it as the perfect fuck book.

Candy was a sensation, no matter which crowd held the contraband paperback in sweaty paws. To people like David Newman, Southern was a hero. Newman would soon earn one of the nicknames Southern bestowed.

Southern loved abbreviations — he would’ve called them abbreves — using a cleaver to shorten words. Fabulous became fab and literature was lit. Dave Newman would soon become Dave New, usually said with an exclamation point. If Southern was wired or riding a high, the young editor was Big Dave New.

So Big Dave New picked up the phone. Terry Southern worked for Esquire from his Connecticut farmhouse, employed as a temp, filling in for Esquire’s fiction editor, Rust Hills, who was off for the summer. Big Dave New had an idea of how best to tap that Terry Southern talent — the perfect story for a man with such esteemed porn-parody credentials.

. . . . . . . . . .

No matter where he was, Terry Southern was always the hippest guy in the room, but he didn’t start out on a particularly hip trajectory. He was born in Alvarado, Texas, “the crossroads of Johnson County,” as it called itself. During his childhood, it was a resume-speed town of only 1,200, a rural community without much to offer. It was a bland and desperate beginning for the man who would become the world’s pre-eminent black humorist by the time the Sixties arrived. The nearest cosmopolitan outpost was Cowtown — Fort Worth, which beckoned from 40 miles up the road.

His father, Terrence Marion Southern Sr, was Alvarado’s town druggist and, as the Depression ground on through the early Thirties, he uprooted his small family and moved to Oak Cliff, a small suburb of Dallas that had been incorporated by the city. After Alvarado, Oak Cliff was massive. It was later known mostly as the home of the Texas Theater, the movie house into which Lee Harvey Oswald ducked to cool his heels after he did or did not single-handedly kill the president of the United States.

But when Terry Southern spent his childhood and adolescence in Oak Cliff, there was no such drama. The village soon became the place from which Southern needed to escape. Reading gave him big dreams and as soon as he could, he vowed, he would be gone.

His mother fed these dreams, giving him the books on which he gorged. He schooled himself with Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Rimbaud, James Joyce, Franz Kafka and William Faulkner. He thirsted for more of the world and — with mom and pop’s consent — spent the summer after his junior year at Sunset High hitchhiking to Los Angeles and then boomeranging to Chicago.

He longed to leave Texas, but after graduation, began at North Texas Agricultural College, up the road in Denton. The school bored him and he soon transferred to Southern Methodist University, back in Dallas. By this time, President Roosevelt had declared war and Southern’s education — and his festering dream of becoming a Great Writer — was put on hold while he served in the Army, stationed at Reading, a largish town on the Thames, 40 miles west of London.

His platoon was deployed to the Continent after D-Day and Southern served in the Battle of the Bulge, witnessing prolific and horrifying death. Later, he spoke little of his military experience. When asked, he muttered that he planned to save his stories for his writing. Yet he never wrote about the war.

The larger effect of the war was to the show the world to the Texas boy. Hitchhiking to LA and Chicago had given him a thirst for anyplace without a twang. Seeing London and Paris showed him that world and transformed him.

Back in the States after the war, he used the GI Bill to enroll at the University of Chicago, home of the Great Books curriculum. What better way to trod the path to the world of Great Writing, he thought. But soon he transferred to Northwestern, on the other side of the City of Big Shoulders, for decidedly non-academic reasons. “One day I visited the campus of Northwestern,” he said, “and saw all these beautiful blue-eyed blondes in their yellow convertibles, or taking the sun by the lake, and I transferred to that school pronto.”

Southern finished his English degree in 1948, then moved to Paris to study at the Sorbonne. The Texas boy was suddenly sharing airspace in lecture halls with Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Jean Cocteau. He stayed in France, and fell in with the crowd that started The Paris Review — George Plimpton, Peter Matthiessen — and, like those other young lions, began pursing a serious writing career, careening into what he came to call (with his penchant for abbreviations) the Quality Lit world.

He was an ex-patriate, hanging in Paris with all of his fellow junior-varsity Hemingways. Literary glory seemed imminent, but he needed money. He concocted a scheme to write an upscale dirty book. He’d studied the form — “db’s” (dirty books) came from Olympia Press in Paris — and was a brilliant parodist. He mimicked the sweaty prose of the genre, but added a sly, conspiratorial literary voice. He wrote the story of a young girl, a pure innocent, and her early carnal adventures. Fellow exiled American Mason Hoffenberg wrote a couple chapters and soon Candy was ready for publication. Since Southern still sought literary legitimacy — and had a non-db manuscript under consideration on a Random House desk in New York — he and Hoffenberg credited the book, finally published in 1958, to “Maxwell Kenton.”

Southern launched his Quality Lit career with two novels, Flash and Filigree the same year as Candy, and The Magic Christian in 1959. He’d fallen in love, and with his new bride, Carol, he returned to the States in time to preside over Magic Christian’s publication. Within a year, he and Carol had a son, Nile.

As the author of two small-but-important novels, Southern would seem to be established in the Quality Lit Game. The safe move was to buy a sportscoat with elbow patches and begin life as a creative-writer professor at a small liberal arts college, somewhere in the gravitational pull of New York.

But Southern didn’t see himself as classroom-ready, so he and Carol (and then Nile) sponged off of friends, overstaying their welcome with a few, until he managed to scrape together enough to buy a dilapidated farmhouse in Connecticut. Southern eked out a modest living. Quality Lit, as it turned out, didn’t pay by the wheelbarrow and Trash Lit did.

He seemed almost ready to pick the path toward that academic career when he edited an anthology called Writers in Revolt, which collected the works of Allen Ginsberg, Jean Genet, Henry Miller and other oft-banned writers.

But then, using his Candy skills, he wrote for a few sex mags (Nugget was one), published a few things in Esquire, got a piece here and there in mainstream publications such as Glamour, as well as some nouveau-naughty rags, such as The Olympia Review, and political journals like The Realist and The Nation.

Desperate for money, he began a push to publish Candy in America under the Southern-Hoffenberg byline. But because of poor copyright registration, he’d see no money for that. Still, word was out: that book … that nasty, funny book passed around surreptitiously … that was the dark work of Terry Southern.

So there he was, that early summer day in 1962, surrounded by a pile of manuscripts (the slush pile!) that had been sent to Esquire, then forwarded to Southern’s Connecticut home. With the regular fiction editor gone for the summer, the magazine asked Southern to sit in. The job was a great gift. It’d be steady money, $125 a week, and get the small Southern family through a couple of months without the usual financial miasma. The job was good, if a little boring, and it allowed Southern enough security to maintain a holding pattern, plotting his next move in the Quality Lit world.

He was gazing at this growing pile of manuscripts when the call came from Big Dave New.

David Newman called Southern at his home and told him he’d love to have him do more than sift through the slush pile. Would he write something for the magazine?

“Grand idea, Big Dave,” Terry barked into the receiver. “Dave New!”

A visit to the office was arranged.

“He came to the magazine for lunch,” Newman recalled. “Meeting Norman Mailer, William Styron, Robert Lowell and all this was very impressive, but meeting Terry Southern was a major event in my life because I never thought I would get to meet the guy. We immediately hit it off.” Newman had read The Magic Christian while in grad school at the University of Michigan. Hired by Esquire after commencement, he loved the access his job gave him to share airspace with his literary heroes, including, now, Terry Southern.

Southern came into the city and went to lunch with Newman. After ordering, Newman made his pitch. He’d come across a brief news item — his desk was fecund with magazines , out-of-town newspapers and press releases begging for attention.

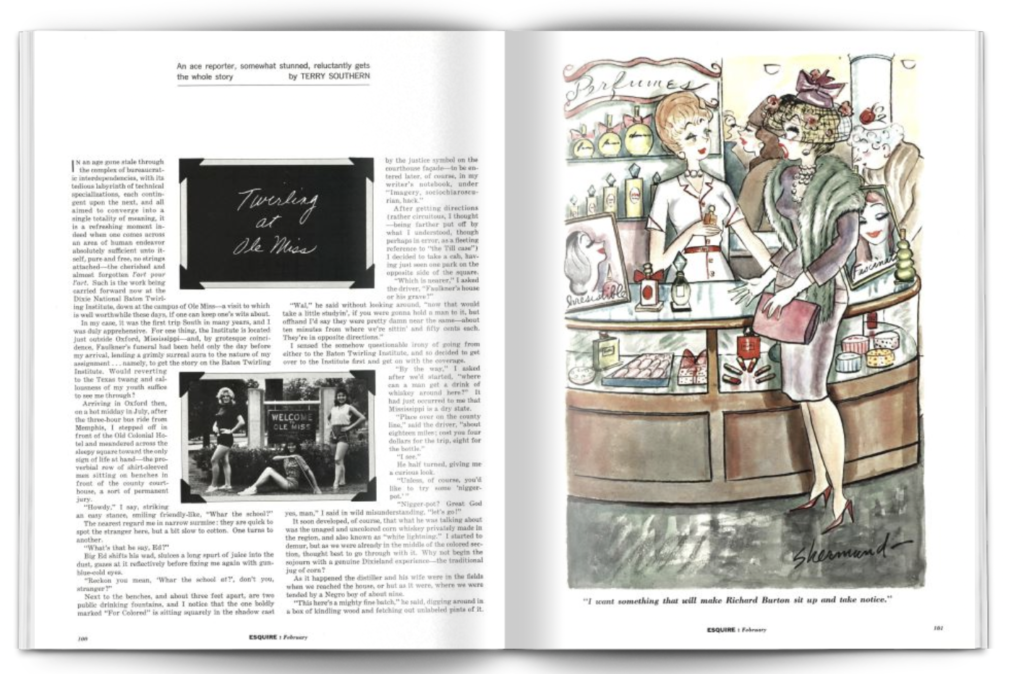

Somewhere in that acrid pile of stool, Newman saw an item about a baton-twirling school on the campus of the University of Mississippi.

Perfect! Brilliant! Newman was struck with a moment of magazine-editor genius. Who was the first writer for a story about a hundred barely-clad teenage girls? Yes! Of course! Terry Southern! Terry Southern: author of Candy, and chronicler of all things nymphet. Imagine: all those pre-pubescent girls in their barely-there baton-twirling outfits, and Terry Southern on hand to observe and report.

“I thought this was so in-and-of-itself instantly satirical,” Newman said, “the idea that only in America would you go someplace to learn to twirl a fucking baton. It seemed so quintessentially American.”

Newman laid out his vision and Southern smiled, immediately accepting the assignment.

William Faulkner, Nobel Laureate in literature and disdainer of conventional punctuation, died on July 6, 1962, and was buried the next day. The funeral was on a Saturday, and businesses around the courthouse square of Faulkner’s hometown, Oxford, Mississippi, closed early in honor of the town’s most celebrated resident. The sidewalks were crowded as the townsfolk gathered to watch the motorcade pass, as the procession moved through the main part of the town to St Peter’s Cemetery.

Southern saw a “grotesque coincidence” that he arrived the following day on the Memphis bus, not for the funeral of a the distinguished Lit Figure, but to watch pubescent girls toss batons into the air. As a Man of Letters, he was of course fascinated by all things Faulkner. He’d missed the funeral, although a true Quality Lit man, novelist William Styron, had attended the funeral on assignment for Life magazine.

Southern had taken the baton-twirling assignment for proximity as much as money. He had hoped to meet Faulkner and gaze upon one of the people who made him want to pursue the lonely trade he now practiced. But now old Bill was dead. At the very least, Southern wanted to see where the Great Man had lived.

Oxford’s courthouse square was, like most of the town, cinematically beautiful. Back at the end of the Forties, Hollywood had come to town to make the film adaptation of Faulkner’s racial-injustice drama, Intruder in the Dust. The classic domed Lafayette County courthouse played a supporting role. Faulkner’s funeral procession had just majestically rolled over these streets the day before, but the next day, as Terry Southern stood there, it was as if nothing had ever happened here, in Oxford, Mississippi. Not a goddam thing.

It was hotter than boiled dog piss. The town square was desolate, Hiroshima-after-the-blast. Southern approached the courthouse, where human life was absent save for a group of local gents, gathered together on a bench — “kind of a permanent jury,” as Southern called them. He withdrew his Texas youth from his gut, and addressed the assembled citizenry in a suitable accent.

“Howdy,” he said, nearly liquid from the humidity and heat — 91 degrees as he faced the jury. “Whar’ the school?”

They gazed at him appraisingly. As he later wrote of the encounter, “They are quick to spot the stranger here, but a bit slow to cotton.”

Finally, one of the old men addressed another of his group. “What’s that he say, Ed?”

Ed (presumably) chewed as he studied Southern. After a short pause, he spewed a saucy jet of tobacco juice, regarded its landing in the dirt of the worn courthouse lawn, then gave Southern the full benefit of his gaze. Finally, he corrected Southern: “Reckon you mean, ‘Whar the school at?’ don’t you stranger?”

He’d been too far gone from his homeland. He could affect the accent but had forgotten the significance of word choice, cadence and other subtleties and nuances involved in communicating with redneck aristocracy. He scolded himself internally: How could he expect to get by in the Deep South long enough to infiltrate this culture and do this story?

The official name of the camp was the Dixie National Baton Twirling Institute and, as Southern approached the campus following a short cab ride, he heard the campers before he saw them. There is something Biblical to the sound of seven-hundred teenage girls shrieking as one, as if they are locusts trebling on the horizon in advance of a divine plague. If not Biblical, then perhaps like the sound of a high-pitched Mongol horde.

The cab had let off Southern on a street bordering campus, and he walked toward the sound, which emanated from the famous Old Miss grove, where the whiskey gentry of Mississippi gathered on football Saturdays with highballs and Rebel regalia.

Southern took pause and beheld the scene. It was as if he’d stepped inside a beehive where the participants weren’t insect but human — young and all female — but working with the frenzy and energy of a flying crew on deadline for a honey harvest.

For a moment, he was stunned mute. Great mother of constipated Christ, he thought. How am I going to write about this?

. . . . . . . . . .

Assuming it was a crow making the trip, Rio de Janeiro was 4,975 miles south of Oxford, Mississippi, and it was there, that same summer of 1962, where another young writer faced Terry Southern’s dilemma: How am I going to write about this?

Unlike Terry Southern, this guy hadn’t published a book. He’d barely published anything except a magazine article here and a newspaper article there. But then he hooked up with Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal company, and was finally seeing his name in print.

But he didn’t see it in print that often. The paper didn’t circulate in Rio.

The thing he wrote for was called the National Observer, which had begun life earlier that year as a Sunday edition of the Wall Street Journal. It eschewed much of the financial reporting of the mothership and instead focused on the sorts of slice-of-life stories that railed the left-hand side of the Journal’s front page daily. These were little-person/big-picture stories, a form of writing the Journal had more or less patented. Stories often began with one person, hooking readers with their travails or triumphs, then pulling back — in a film terms, from a close-up to a long-shot — to show this little person as endemic of some big-picture issue in the country.

Barney Kilgore, the Journal’s editorial czar, had liked those stories and thought he could exploit the talent of Journal staffers who produced those, and build a whole publication around them. Since it would appear on Sunday, the National Observer would have long, leisurely pieces that ambled around until they made a point, much like the casual-essay form that E.B. White had crafted during his years at the New Yorker.

The Observer’s staff soon learned that Kilgore’s big dreams were not matched by a big budget, and they found it hard to produce the high-quality publication Kilgore so desperately wanted. The payroll included only a few Observer-only editors and even fewer Observer-only reporters. Mostly, the staff was rewriting stories from the mound of local newspapers that arrived in the daily mail, or injecting style into dry Associated Press reports. What they needed, they mused, was a dedicated army of reporters.

Kilgore tried to put lipstick on this journalistic pig. “We don’t need more people telling us what has happened, as much as we need people who can put together events and explain them,” Kilgore told investors. Time magazine started out forty years before using much the same approach — rewriting the reporting of others. If it worked for Henry Luce, Kilgore reasoned, it could work for Dow Jones.

Easily said, not easily done. Jerry Footlick was one of the in-the-trenches editors when the National Observer started up. “In the beginning, there was a lot of reprinted stuff,” he said. “It was all written in the newsroom for the first year or two, with a lot of reprints.”

It struggled along, an interesting experiment that earned some attention in the press, and caught the eye of a young, failed freelance writer who sent a letter to Clifford Ridley, the Observer’s features editor.

The letter was an extended boast — all hat and no cattle — but the writer said he was going to South America and would be sending a screed now and then that he expected to be published in the Observer. He also expected, he informed the editor, to be paid at the highest freelance rate.

Ridley was amused by the young writer’s cojones. In his head, he’d been mulling a response to the kid, something on the same level of pride and whimsey. But before he could respond, the kid sent in his first piece. It was a semi-political essay, certainly worth publishing, and almost immediately something else arrived in the mail, a much-smudged envelope with an exotic postmark: Aruba.

Inside the envelope was a story that unfolded with dramatic leisure, fully drawing in Ridley.

The story began: “The Trocadero Bar on the Caribbean island of Aruba is spacious, sunny, and breezy, with slated doors and a long white porch that faces the sea. It’s the kind of place where you might discover Somerset Maugham, or the ghost of Humphrey Bogart eyeing you sullenly from the other end of the black marble counter.”

Ridley was charmed. Beats the hell out of rewriting the Los Angeles Times, he thought.

He wrote back to the kid, asking for more, and the stories came in, each accompanied by a letter to Ridley that told of the madness and menace behind gathering information for each story. After Aruba, the envelopes came Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, Paraguay, and, finally, Brazil.

Ridley’d never met this guy, but through his stories and especially through the cover letters that came with each piece, he began to feel kinship with this Hunter S. Thompson kid.

Hunter Stockton Thompson was born in Louisville during the Great Flood of 1937, the son of insurance man Jack Thompson and his much-younger wife, Virginia. They lived in the middle-class enclave of the Highlands, a nice suburb soon outpaced by other, nicer suburbs. Still, it was a good if unexciting life for the three Thompson boys, Hunter, Davison and James.

But when Jack Thompson died suddenly, life changed. Fatherless, teenage Hunter Thompson was set adrift, often staying out all night and committing small acts of delinquency. Louisville was a one-stop center for vice, since it produced both tobacco and alcohol, including most of the world’s bourbon supply. Free from fatherly disdain or punishment, Thompson indulged in all available vices and was, by 13, already a chain smoker and a functioning alcoholic.

The pressure of managing three boys was too much for Virginia Thompson, as she struggled to keep the family financially afloat. She went to work at the reference desk of the Louisville Free Public Library, which shamed her eldest son. None of the mothers of his posh friends worked (though not from an affluent background, he ran with the scions of the city’s wealthy class), so he was appalled not only that she worked, but that she worked so publicly, in view at the main desk of the downtown library.

For her part, Virginia Thompson worried about her eldest son’s prolific bad habits and his late nights. She’d stay up sometimes into the fissures of dawn, deep in the sauce, worrying about her errant oldest son. It was as if he became someone else when his father died. Virginia asked her mother to help manage the family. Memo (pronounced mee-mow) moved in and did her best to wrangle the boys.

Thompson missed his high school graduation because he was serving a two-month jail term for attempted robbery. He was released after a month for good behavior and was encouraged by the court to enter the military. He enlisted in the Air Force, thinking he’d become a pilot. Instead, he was told he would be trained as an electrician.

But then he discovered journalism. Eglin Air Force Base in the Florida panhandle had its own newspaper, the Command Courier, and it needed a sports editor. Thompson lied, telling the editor that he’d covered sports as a freelance for his hometown Courier-Journal, the family-owned Louisville newspaper often ranked as one of the country’s five-best dailies. After learning of the opening at the Command Courier, Thompson had gone to the base library and found the lone book about journalism in the collection. He memorized the key jargon of the trade and fooled the editor during the interview. He got the job.

Thompson was not a good match for the United States Air Force. He didn’t care for waking up early, disdained discipline and routinely questioned authority.

Being sports editor was the closest he could get to being a civilian. He got to set his own hours and, since he’d moved off base, he didn’t have to wake with the other cattle in the barracks, and he got to travel a lot.

Eglin had basketball and football teams. During the Suez Crisis in 1957, several professional football players serving in the reserves were assigned to Eglin, including Green Bay Packers quarterback Bart Starr and his prime receiver, Max McGee. Wherever the base football team (or basketball team or baseball team) went, their devoted chronicler, Hunter S. Thompson, followed.

He moonlighted for the local civilian newspaper, the Playground News, and when he was encouraged to leave the Air Force — it was an honorable discharge, despite the urging of his commanding officer — he began his career in journalism.

It was a terrible start. He left the Jersey Shore Herald (despite the name, it was in a landlocked and dreary part of Pennsylvania) after totalling a colleague’s car and pissing off an advertiser. He worked at the Middletown Daily News in New York and was fired for destroying a vending machine. He spent a winter in an unheated cabin in upstate New York, beginning work on what he thought would be the Great American Novel, his autobiographical story of high school days in Louisville, Prince Jellyfish. He’d also worked as a Time magazine copy boy, but spent most of his time in his cubicle retyping books by Hemingway and Faulkner and Fitzgerald. He didn’t change a word; he just retyped the books, to try to understand the genius behind the writing. “I’m very much into rhythm — writing in a musical sense,” he said. “I like gibberish, if it sings.”

But he spent too much time retyping books and not enough funneling copy for his editors. He also abused his food-and-drink privileges during the magazine’s weekly after-deadline buffet and booze blast. Thompson invited friends and they drank nearly all of the alcohol before the magazine’s heavy hitters could make it to the bar.

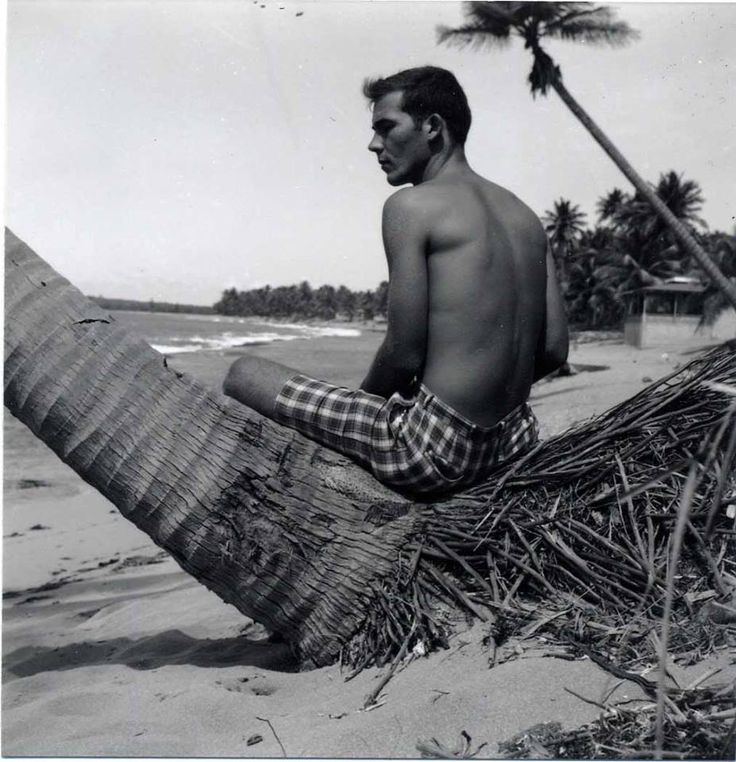

Paradise beckoned at the dawn of the Sixties, when Thompson saw an ad in Editor and Publisher magazine. Someone was looking for writers for a start-up magazine that would be “the Sports Illustrated of the Caribbean.” With a small amount of money left to him by his recently deceased grandmother, Memo, he set off for Puerto Rico.

The new magazine, Sportivo, couldn’t even be the Sports Illustrated of East McKeesport, Pennsylvania. It was a wretched and horrifyingly dull publication, focused mostly on bowling. Thompson’s job was to cruise the San Juan alleys each night and get names — lots of names — so that the editor could fill Sportivo with exploits by local bowlers. The theory was that people would buy the magazine to see their names in print.

Thompson rebelled. The work was beneath him, he told the editor, and he quit. Fortunately, he’d lured a high school friend to Puerto Rico and he had a job at the San Juan Star. Paul Semonin first allowed Thompson and then his girlfriend, Sandra Conklin, to move in with him. Thompson set out to write the Great Puerto Rican novel, The Rum Diary, toiling away at the beach shack the three of them shared.

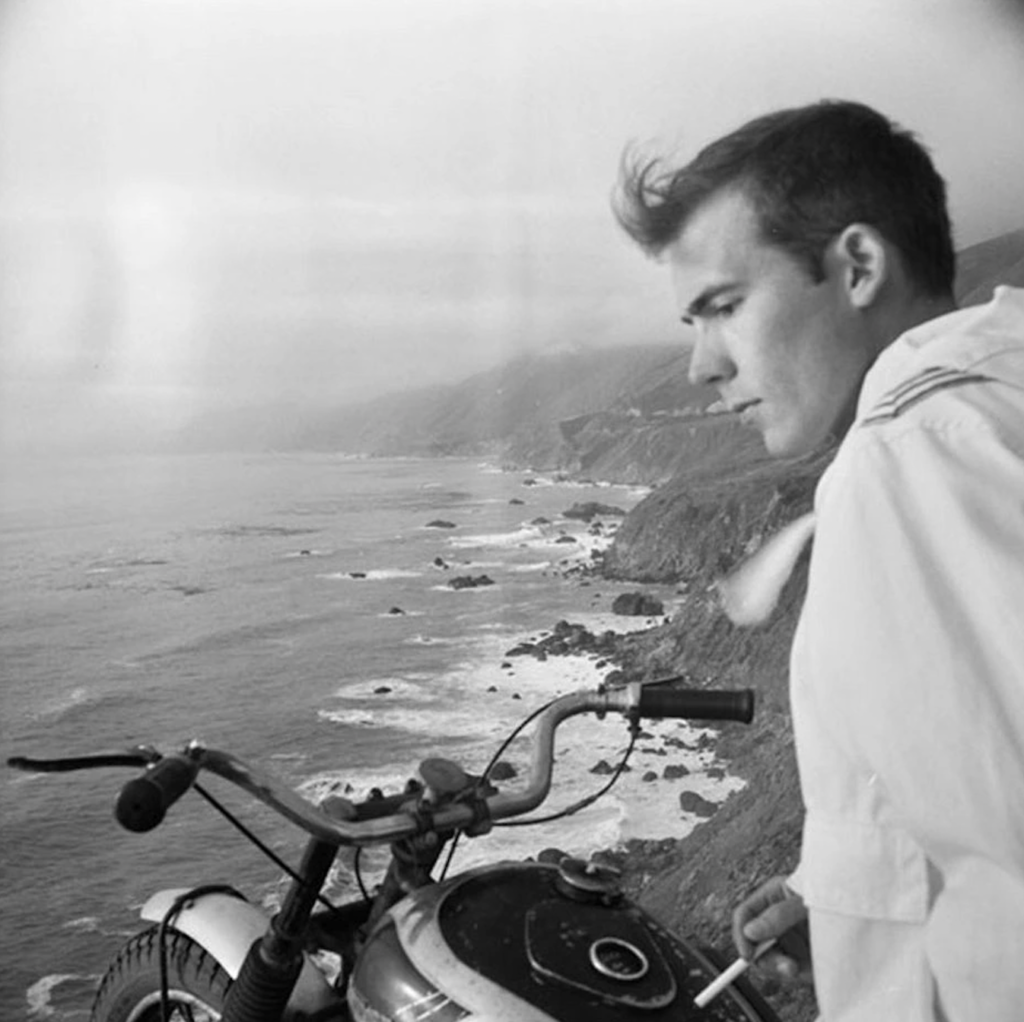

Eventually, Hunter and Sandy escaped to the States via a long stopover in Bermuda. They lived for a year in Big Sur, on the rocky coast of California, serving as caretakers for an estate.

Thompson sold his first magazine article to Rogue, a lower-level Playboy imitator. “Big Sur: The Garden of Agony” told of the libertine life in Big Sur, centered on a local resident, the writer Henry Miller. Known for his erotic novels, Miller’s books had been long banned in America. Thompson yearned to meet him and took to waiting at the group mailboxes at the head of the road, hoping Miller would come for the post. He never did, and they never met.

The Rogue article offended the clerisy of Big Sur and Thompson residents encouraged to leave, with a ferocity one step below using torches and pitchforks. From there, Thompson moved again — first to New York, then for points south. He read about this new thing, the National Observer, looked up the name of the features editor, Clifford Ridley, and sent him a letter, promising brilliant, analytical writing in return.

Thompson’s collaboration with Ridley became a fulcrum in the young writer’s career. When the first smudged envelope arrived from Aruba, Ridley showed the piece to Bill Giles, the Observer’s managing editor. Giles was impressed.

“Bill gave Hunter a contract for six pieces at $1,000 apiece,” staff editor Jerry Footlick said. “That was a lot of money in the Sixties. There were some other staffers, old Wall Street Journal types, who were Bill’s top editors beside him, who thought Thompson was a total kook. Yes, a good writer, they said, but you couldn’t trust him. But Bill had great faith in Hunter from the start.”

It was a right-place / right-time moment for both sides of the equation. Thompson needed the money and legitimacy as a real goddam Dow Jones journalist. And the Observer, which had been struggling to establish its voice and did not have a clearly defined style, relished its new, flashy correspondent and his far-flung adventures.

“One complaint we heard about the Observer was that it was too dull,” Footlick said, “Well, Hunter was not dull.”

As a freelance, Thompson had sold the occasional feature article to newspapers such as the New York Herald Tribune or the Baltimore Sun, but his writing was generally too loose and ragged for most mainstream newspapers and not slick enough for America’s major consumer magazines.

Thompson’s sojourn south began with a return to Puerto Rico, where he commiserated with rum and friends, then hopped a boat for a ride to Colombia, paying smugglers forty dollars for passage. In Aruba, he did a semi-conventional piece illustrated with a self-portrait (he identified himself as “an American tourist”) lounging on the beach with a book and a brew. Nobody at the Observer had laid eyes on Thompson, so they didn’t know he served as his own model.

The trip with smugglers helped the young writer find the meat of his first major Observer piece, “A Footloose American in a Smuggler’s Den.” As was his practice, the story featured Hunter Thompson as its central character.

After three paragraphs of imitation Hemingway, the story turned into comic misadventure. Upon arriving in a tiny village as “the first tourist in history,” Thompson is greeted by the entire population “staring grimly and without much obvious hospitality.” In this village, Thompson learned, men wore neckties knotted just below the navel, and nothing else. To make himself welcome among the villagers, Thompson concocted a plan. “I decided at the first sign of unpleasantness, I would begin handing out neckties like Santa Claus — three fine paisleys to the most menacing of the bunch, then start ripping up shirts.”

Readers ate it up. Because he wrote in the first person and in such distinctly American cadence, subscribers found an easy entree to the foreign world. After Aruba and Colombia, he was off to Peru, then Ecuador, Bolivia, Uruguay and, finally, Brazil.

Though the thousand-bucks-per-article rate was good for the times, Thompson’s travel cut into his wallet. He thirsted for each Observer envelope and lived paycheck to paycheck, sometimes finding too much month at the end of the money.

At each stop, he spun off his adventures, always in the first person — the only way he knew to tell these tales. His writing was tethered to Dow Jones, so despite his wallowing in the first person, he had to remain somewhat conventional in his storytelling.

It was like math without numbers. With each story, Thompson indulged in problem-solving: how do I write about this, and how do I write about this. He was in virgin territory. Few reporters found themselves in caves with tin miners or sitting across a campfire from a smugglers.

How am I going to write about this?

Each dispatch to the Observer office in suburban DC was accompanied by a cover letter to Ridley, which Thompson wrote in an intimate and conspiratorial just-between-us tone. About Ecuador, he wrote, “I could toss in a few hair-raising stories about what happens to poor Yanquis who eat cheap food, or the fact that I caught a bad cold in Bogota, because my hotel didn’t have hot water, but that would only depress us both. As it is, I am traveling half on gall.”

Ridley loved the letters and Thompson, encouraged, continued to speak to Ridley — a man he’d yet to meet — in a friendly and decidedly non-Dow Jones voice.

“I no longer give a fuck,” Thompson wrote from Rio de Janiero, “but don’t translate as evidence that I am getting soft & fat & I only want to do the easy stories. At the moment, in fact, I don’t want to do any stories.” After a brief discussion of logistics, Thompson continued: “It ain’t the stories, Clifford. Those are easy. It’s the goddam awful reality of life down here…. Hell, I can’t even deal intelligently with your letter. I can barely do anything. All I know is that I have a ticket from Rio to New York; that is a tremendous factor in my thinking. As a matter of fact it is all I can really think about.”

Ridley was a company man, steeped in Dow Jones culture. Wall Street Journal writing was suit, necktie and Florsheims. Thompson’s Observer pieces were no-jacket, loosened collar. But this voice in the letters was different — shirts of wild blue swirls on egg-yolk backgrounds, khaki shorts and Chuck Taylor All-Stars. The letters were not Observer-ready in their full form, but Ridley loved the voice they carried and wanted to share them.

He knew that Thompson, certified square peg, could never fit in the round hole that was Dow Jones. He could try to write company copy, but it would be like putting on an ill-fitting suit. One of Thompson’s friends, Bob Bone, saw the disconnect between his pal and the world of straight journalism. “During the Rio days,” Bone recalled, “Hunter talked a wild game, but he was writing pretty straight copy. He had to get published by the National Observer to pay the rent. But he discovered his success later, when he began to write just like he talked.”

Or wrote stories the way he wrote letters.

Each envelope came with the no-jacket loosened-tie voice Thompson put on for the Observer. But the cover letter was tucked in, a here’s-how-I-got-that-story account from writer to editor. These were often hilarious, because Thompson didn’t write them for publication. He knew he couldn’t write like that for Dow Jones, so he was uninhibited and free. It was iceberg stuff, all the below-the-surface stuff that readers didn’t see, but was essential for keeping the story — tip of the berg — above the water.

When a Thompson envelope arrived, Ridley ripped it open and sat at his desk, cackling. The enclosed story was good, but the letters, hilarious and profane, were some of the best stuff Ridley’d ever read. He saved them in a drawer. Each new story carried another wild tale intended for an audience of one. Ridley kept them handy, so he could re-read them for a hoot now and then.

Then Ridley had an idea. The Observer was still finding its way and needed something to set it apart from the other weeklies, slick magazines or otherwise (the blanket-sized newsprint Observer being otherwise). Maybe this correspondent, Hunter Thompson, could provide that difference.

Ridley picked his favorite passages from the letters and assembled them, using ejaculations of type (@#$%^&*) in place of the profanity. He first ran it by his colleagues up the ladder. A few of them were dubious, but Ridley was passionate and he offered the ultimate argument in favor of publishing excerpts from a correspondent’s copy: It was essentially free content.

That won the day and, with Thompson’s permission, “Chatty Letters During a Journey from Aruba to Rio” was published on New Year’s Eve 1962.

The collection brought readers into the tent, to see how their stories were discovered, chronicled and eventually merchanted. “Chatty Letters” showed Thompson informing Ridley of the agonies and indignities that beset him during the reporting and writing. The story there in Ridley’s paws was there despite the frenzy that spawned its creation: “Some S1/2&?& has been throwing rocks at my window all night and if I hadn’t sold my pistol I’d whip up the blinds and crank off a few rounds at his feet. As it is, all I can do is gripe to the desk. The street outside is full of thugs, all drunk on Pisco. In my weakened condition I am not about to go out there and tackle them like Joe Palooka. It is all I can do to swing out of bed win the mornings and stumble into the showers, which has come to be my only pleasure. I am beginning to look like the portrait of Dorian Gray; pretty soon I am going to have the mirrors taken out.”

Ridley recognized the distinct voice Thompson used as he related his tales of reporting. The finished articles were good — different from the usual Dow Jones fare, certainly — but well above the norm of everyday journalism. But these letters — Ridley saw in them something their author didn’t yet see: a different, and original voice.

It would be at the end of that decade when Thompson came to the realization that getting the story could be the story.

. . . . . . . . . .

Three-thousand miles north, in humid, clammy-underarm Oxford, Mississippi, Terry Southern wondered what he’d gotten himself into. There’s no way he could write about this, this baton-twirling camp, with these girls in their skimpies. He was a grown-ass man, a husband, a father, a professional writer. How could he write about this?

He couldn’t, of course, and what came out when he sat down at the Underwood was a confession, a blood-letting, an admission that while being sent down South to get a story he had failed to get that story. What he got was a different story: a story about trying to get a story.

Terry Southern issued no manifesto, but in the wake of his visit to the Ole Miss campus to watch young girls toss batons, he wrote one of the first examples of a form that would within a few years become considered the sole intellectual property of Hunter S. Thompson.

Gonzo journalism — Thompson’s name for his style of writing — didn’t have its name when Esquire published “Twirling at Ole Miss.” Though he would continue to dip his toes in the waters of journalism at key moments in cultural history, Southern soon left the Esquire slush pile behind and went off to write some of the classic films of the decade: Dr Strangelove, The Loved One and Easy Rider.

Southern made no pact to cede this approach to journalism to the young writer living hand-to-mouth south of the equator. It’s likely they were unaware of each other. Southern might’ve been reading the Observer. Thompson, fan of wicked, funny literature such as JP Donleavy’s The Ginger Man, admired Southern’s Magic Christian. But in the early sixties, getting copies of Esquire in remote South American outposts was difficult.

Yet they were taking tentative and simultaneous steps toward the same goal — to a metajournalism, journalism about journalism.

In New York, a Yale-minted PhD sat at his desk in the offices of the New York Herald-Tribune. He’d gone straight through school, following the road of American education all the way to its end, to an Ivy League doctorate. Academia beckoned, breaching before him like a white whale. Yet he took another path, thirsting as he was for the vaunted Real World, after so many years in the wilderness of institutional education.

He became a newspaper reporter. What could be more real-world than that?

He covered zoning-board meetings in his first job at the Springfield Union in Massachusetts, then arrived at the Washington Post in 1959, where he was mostly misunderstood by the too-conventional editors. By 1962, he was in the newsroom of the Herald-Tribune, the premier writers’ paper in the city.

From his desk, he beheld the landscape of journalism, with some of the greatest reporters of his generation a couple seats away. Still new to the Trib, he was trying to figure out how to stand out, how to be different.

Southern and Thompson might not be aware of what the other was doing, but Tom Wolfe, sitting at his newsroom desk, was watching. When he read “Twirling at Ole Miss,” he saw a breakthrough. “It was the first example I noticed of a form of journalism in which the writer starts out to do a feature assignment,” Wolfe later wrote, “and ends up writing a curious form of autobiography. It is not autobiography in the customary sense, because the writer has put himself there for no other reason than to write something.”

Southern was sometimes credited with making the key breakthrough to what became “New Journalism.” (Later, when it was no longer new, it became known by stodgier terms like “literary journalism” or “creative nonfiction.”) “Twirling at Ole Miss” was unlike anything a mainstream magazine had published before, and was a shot across the bow of the Sixties. This new iteration of the magazine, now edited by a North Carolinian named Harold Hayes, was not your father’s Esquire.

Gifted not only as practitioner but also as an analyst of American journalism, Wolfe was one of the first to acknowledge Terry Southern’s role in breaking the silly rules of that era’s journalism, and also one of the first to consider Thompson, the outlaw journalist, a maestro of the form.

In the end, it didn’t matter who was there first or when or how the revolution erupted, but that it happened at all. There were strict rules of journalism that had been evolving over the grand sprawl of the Twentieth Century. Now those rules were crumbling and everything was fair game. Now the fun was about to kick in.

Let the weenie roast begin! The Sixties yawned ahead, and craziness loomed. But, as Tom Wolfe liked to say, it would be pandemonium with a big grin.