The Scribner Encyclopedia

of American Lives

Edited by Arnold Markoe

Gale, 2006

This volume of the semi-annual update on dead people included my essay on the death of Hunter S. Thompson.

This volume of the semi-annual update on dead people included my essay on the death of Hunter S. Thompson.

Here is the text of my entry:

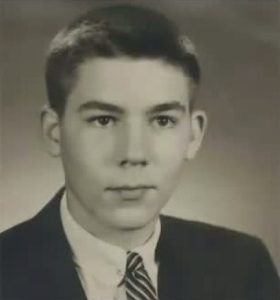

Thompson, Hunter S(tockton) (b. 18 July 1937 in Louisville, Kentucky; d. 20 February 2005 in Woody Creek, Colorado), iconoclastic writer, self-described doctor of gonzo journalism, considered one of the greatest comic writers of the late 20th Century.

Thompson was born to a Louisville insurance salesman and his librarian wife, the oldest of Jack and Virginia Thompson’s three sons. He began writing for his neighborhood newspaper, the Southern Star, when he was 10 and developed interests in sports and literature. As a teen, he joined Louisville’s prestigious Athenaeum Literary Society, an honor usually reserved for the children of Louisville’s elite, but Thompson was distinguished mostly by his considerable charm and not his ambitions as a writer.

Thompson was 15 when his father died and the family was deeply affected by the loss. Work took Virginia Thompson away from home and her eldest drifted toward a career as a juvenile delinquent. He missed his high school graduation because he was jailed on a robbery charge and, upon release, enlisted in the United States Air Force. While stationed in the Florida Panhandle, Thompson began working as sports editor and columnist for the base newspaper, the Command Courier, and working off base for a civilian newspaper. Enjoying both the power (primarily the access to events) and the audience of the journalist, Thompson believed he had found his niche. After leaving the service, he ran through a few jobs on small newspapers and served a brief stint as a copy boy for Time magazine. While living in near-poverty in New York, he began writing his first novel, the still-unpublished Prince Jellyfish.

A job with a sports magazine in Puerto Rico took him to the Caribbean, the setting for his second novel, The Rum Diary (finally published in 1998). He began freelancing for the New York Herald-Tribune and The National Observer. The Observer, conceived as a Sunday edition of the Wall Street Journal (though published on Mondays), was a feature-heavy paper that gave Thompson space and license to develop his journalistic vision. He wrote about tin miners, smugglers and renegades – not the usual sort of material in most American newspapers. The editors admired his insights and storytelling, but when Thompson returned to the United States after his years in the Caribbean, his working relationships with Observer editors soured.

Thompson married Sandra Dawn and moved to San Francisco, where he supported himself as a day laborer while his wife worked as a motel maid to supplement his meager freelance income. Their son, Juan Thompson, was born in 1964. Thompson’s luck changed when a piece he wrote for The Nation on the Hell’s Angels motorcycle club, “Losers and Outsiders,” caught the attention of publishers. He signed a deal with Ballantine Books for Hell’s Angels (1967), published after he spent a year riding with the club and, eventually, being stomped by them.

He moved to Woody Creek, Colorado, near the jet-set resort town of Aspen, and spent the remainder of his career at Owl Farm, which he called his “fortified compound.” He got involved in politics at the local (running for sheriff) and national levels (covering the 1968 campaign, including an exclusive interview with the press-shy Richard Nixon). Still, he fell back into the hand-to-mouth existence of most freelance writers. Eager for a followup to Hell’s Angels, Thompson signed a deal with Random House for a big book on the death of the American Dream, but beyond a series of visionary letters to his editor, never seemed to get a grasp on the concept or on the story he wanted to tell.

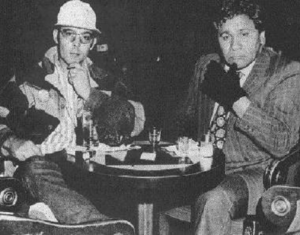

His made a series of breakthroughs as the 1970s began, beginning with an association with the short-lived magazine Scanlan’s Monthly, edited by Warren Hinckle. Hinckle sensed that Thompson’s eye on American culture would provide a unique vision and sent him back home to Louisville to cover the Kentucky Derby. Hinckle teamed Thompson with British artist Ralph Steadman, whose chaotic drawings matched Thompson’s over-the-top prose. It was not just a horse race, in Thompson’s eyes. The Kentucky Derby was an orchestrated clash of cultures – youth against the establishments, haves against have-notes. He conceived the article on a grand scale but, frustrated by a relentless deadline, Thompson was unable to put together the lucid and coherent report on the Derby he assumed the magazine wanted. He began faxing unedited pages from his notebook to the editors and assumed he would never write for a major magazine again. To his surprise, the magazine printed “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” verbatim and it was hailed as a breakthrough in American journalism. One friend, Bill Cardoso of the Boston Globe, congratulated Thompson, calling it “pure gonzo.” The name – derived from a term used to describe the last man standing at a bar – became the description for whatever Thompson wrote. He embraced “gonzo journalism,” sometimes referring to himself as a “doctor of gonzo journalism.” Asked to define gonzo, Thompson was usually elusive with a straight definition. He called it “free lunch, final wisdom, total coverage.” The best definition of gonzo was simply “whatever Hunter Thompson writes.” His style was so distinctive that other writers appeared ridiculous trying to copy it.

Thompson still labored on his “Death of the American Dream” project, but had little luck. It was while running for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado, that Thompson got to know Jann Wenner, editor of Rolling Stone. Thompson went to San Francisco in 1970, hoping the editor of America’s most popular youth magazine would be interested in a story on the campaign. Wenner solicited Thompson for an article on the campaign, then gave him a few other assignments.

Thompson’s major work drew from two failed magazine assignments in Las Vegas. In 1971, Sports Illustrated assigned him to cover the Mint 400 motorcycle race. Since he was already in Las Vegas on another magazine’s expense account, Wenner assigned Thompson to cover a law-enforcement conference on drug abuse for Rolling Stone. Though he had been at this point stymied for years on the American Dream project, Thompson was able to take some of his concept and meld it with the two failed magazine stories into the book that became his masterwork, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1972). The book appeared first as a two-part article in Rolling Stone, illustrated by Steadman

After the success of Fear and Loathing Las Vegas, Wenner agreed to have Thompson cover the 1972 presidential campaign for the magazine. Thompson’s reporting included occasional flights of fancy and healthy doses of skepticism and opinion. The more traditional reporters from major newspapers and networks at first derided him because of his unconventional manner and controversial habits (he rarely worked without a drink in his hand). But soon those reporters began to admire him, once they read his dispatches in Rolling Stone. Wenner gave Thompson license in his reporting to say the sorts of things the other reporters thought but could not write. Thompson saw that the reporters were merely being used by the politicians and that the press traveled in a pack, basically reporting the same story, with only slight variation. He pointed out this tendency toward pack journalism to his traveling assistant from Rolling Stone, Timothy Crouse, and encouraged him to write a book on the political press. The result, The Boys on the Bus (1973) became a highly regarded analysis of the weakness of modern journalism. Thompson’s own reporting of the campaign was collected in the book Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail (1973).

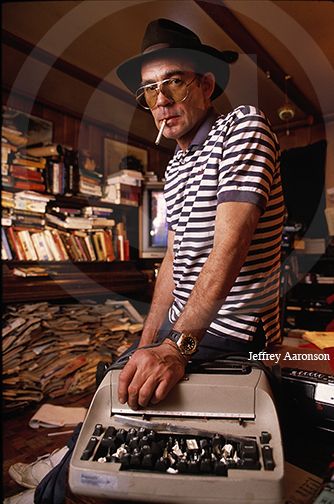

The Watergate scandal brought down Thompson’s nemesis, President Richard Nixon, but it was not Thompson’s kind of story. He had made his name as a writer by avoiding the standard conventions of journalism, including the requirement of objectivity. Thompson was the opposite. He played the largest role in his stories and no matter what subject he was assigned to write about, he ended up writing about himself. He’d built his reputation with Hell’s Angels, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail – three books that allowed him to indulge in first-person narrative. He made the process of getting-the-story into the subject of his writing.

Watergate was not a Thompson-style story. The story was driven by Congress, as the U.S. government did its own laundry, moving deliberately toward impeachment. There was no place for Thompson inside the story and though he wrote about it, these efforts at political commentary were not his strength. He was not comfortable to merely be an observer.

After Nixon’s resignation and exile, Thompson faded from the scene for a few years. In some ways, Nixon had been his muse. With Nixon gone and a man Thompson admired (Jimmy Carter) in the White House, his output slowed. He covered the fall of Saigon for Rolling Stone in 1975, but negotiations over pay and benefits with Wenner angered Thompson his complete story was not to be published in the magazine for another 10 years. Thompson stayed in the forefront of American culture, though, with a collection of his early writings, The Great Shark Hunt (1979). Occasionally a magazine assignment would turn into a lengthy manuscript – hence The Curse of Lono (1983), a book-length collaboration with Steadman that grew from an article on the Honolulu Marathon.

Now divorced, Thompson took occasional assignments but it was not until his signing as a columnist with the San Francisco Examiner in the mid-1980s that he increased his output. Generation of Swine (1988) was a collection of Examiner columns. Though he was still the mad-dog gonzo reporter he had been for Rolling Stone, he toned down some of the language and lifestyle references since he was writing for a mainstream newspaper.

Starting with Generation of Swine, Thompson’s production increased and he began publishing regularly near the end of the 1980s, inspired in part – so he claimed – by the ascent of the first President Bush. He’d finally found someone to replace Richard Nixon as his muse.

Songs of the Doomed (1990) contained sections of Prince Jellyfish and The Rum Diary and generous helpings of memoir. It also included a long section devoted to a 1990 run-in with the law. Local authorities had raided his home, suspecting that an assault had occurred. That charge did not hold, but police did find trace amounts of drugs. Thompson fought this “lifestyle bust” (his term) and was acquitted.

Better Than Sex (1994) focused mostly on the 1992 presidential campaign but it seemed the most thrown together of his books, with several of the pages reproductions of Thompson’s faxes. One of the characteristics of his journalism was his involvement in the stories he covered. For the Fear and Loathing book on the 1972 campaign, Thompson was in the middle of the story. This time around, he covered the 1992 presidential campaign mostly by watching CNN’s coverage.

He still experimented with the boundaries between fiction and fact with Screwjack (originally published in a limited edition in 1991, published commercially in 2000). He also toiled on another novel, Polo is My Life, portions of which were published in Rolling Stone.

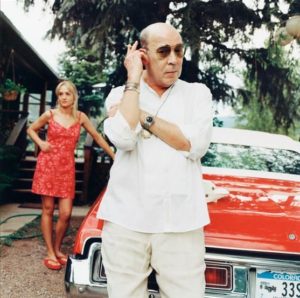

A tireless correspondent, Thompson saved a copy of nearly every letter he ever wrote. He filled three huge volumes with his correspondence – The Proud Highway (1997), Fear and Loathing in America (2000) and The Mutineer (2007), forming a loose autobiography. Kingdom of Fear (2003) filled in a few gaps in his life story. He signed with the Web site of sports network ESPN to write a column. Although ostensibly about sports, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, turned Thompson back to politics. His columns were collected in Hey Rube (2004).

Thompson married Anita Bejmuk in 2004. Portrayed twice in films – by Bill Murray in Where the Buffalo Roam (1980) and by Johnny Depp in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) – Thompson was also (to his chagrin) the model for the character of “Uncle Duke” in Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury comic strip.

Thompson committed suicide on Feb. 20, 2005, in his home at Woody Creek. A memorial on his farm the following summer featured Thompson’s ashes blasted from a tower modeled after Thompson’s trademark Gonzo fist, while Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” played, echoing through the mountains.

On Thompson’s death, writer Tom Wolfe compared his friend to Mark Twain, suggested that Twain was the 19th Century’s gonzo writer. Thompson, he said, was the 20th Century’s “greatest comic writer in the English language.”

Bibliography: William McKeen’s Hunter S. Thompson (Twayne, 1991) is a study of Thompson’s career through Songs of the Doomed. Three biographical works appeared in the early 1990s: Hunter by E. Jean Carroll (1993), Fear and Loathing by Paul Perry (1992) and When the Going Gets Weird by Peter Whitmer (1993). Gonzo: An Oral History by Corey Seymour (2006) is a tribute to Thompson that grew from Rolling Stone’s memorial issue to its most famous contributor.

Books by Hunter S. Thompson: Hell’s Angels (1967); Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1972); Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72 (1973); The Great Shark Hunt (1979); The Curse of Lono (1983); Generation of Swine (1988); Songs of the Doomed (1990); Screwjack (1991, 2000); Better Than Sex (1994); The Proud Highway (1997); The Rum Diary (1998); Fear and Loathing in America (2000); Kingdom of Fear (2003); and Hey Rube (2004).