Woodstock Without Tears

Appeared in the Tampa Bay Times, August 14, 2009

It’s a good thing we didn’t have Twitter feeds or live blogging 40 years ago. If we had, then the Woodstock festival would have lost much of its mystique. More than 400,000 fans were there. The rest of us just have to wonder what it was really like.

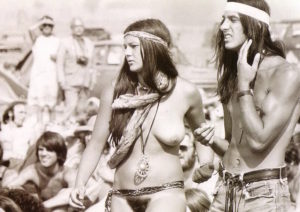

Even though the iconic documentary film that came out in 1970 gave the rest of us the illusion of being there, there’s only so much you can fit into a movie — even a three-hour film that deified rock stars. Lots of artists were left out. Theater patrons could easily use the restroom, unlike actual festivalgoers, and film does not allow for scratch and sniff, which would offer a fuller Woodstock experience.

Back to the Garden, Pete Fornatale’s celebration and oral history of the event, won’t give us the you-were-there feeling. Face it, friends — nothing will. If you weren’t there, you weren’t there. And if you value good hygiene and the concept of personal space, maybe it’s a good thing you stayed home (or, more likely, weren’t born yet).

But with the event’s 40th anniversary this weekend and the inevitable media orgy, this book makes a pleasant companion. Watch the movie, play the music, read the book. You still weren’t there (unless you were), but maybe you can understand the festival a little better.

When music impresario Bill Graham died, some of his friends put together an oral history of his life. The chapter on Woodstock was the most fascinating, riveting part of that book. Fornatale doesn’t quite measure up, partly because of the disjointed nature of oral history. The jerky stops and starts of group storytelling undercut the nature of narrative. (Now, a narrative of Woodstock — there’s a concept.)

Fornatale organizes the story around the order of performances, so it starts with Ritchie Havens and ends with Jimi Hendrix. Friends and fans step forward to offer remembrances of the artists and their sets. It’s all strung together with Fornatale’s agreeable if somewhat cliched comments. (Of Janis Joplin, he writes: “The ‘little girl’ [in Janis] never went away. Buried deep inside of her, that vulnerability undermined every relationship in her all too brief life.”)

Despite these flaws, any fan of rock music probably needs — and will enjoy — this book. Pick up the new and expanded DVD of the documentary, swathe your body in patchouli and have a good old time pretending you were there.