Southern Exposure

Not sure where this memoir came from. Al Satterwhite asked me to write something for his book of photos of the South, mostly in the 1960s and 1970s. The photos are brilliant. My prose is far from that. I think this unfinished piece was an effort to provide an introduction to his book-in-progress. So here are some thoughts and memories of a nomadic kid in the South in that era.

. . . . . . . . . .

Copyright © 2025 William McKeen

I got my own way of talking, but everything gets done

with a southern accent where I come from

TOM PETTY

I began to get the questions not long after I moved to Boston. “What part of the South are you from?” they’d ask.

I was at first startled. “What makes you think I’m from the South?”

Then came the indulgent smile. “Your accent, of course.”

But I don’t have a Southern accent. I grew up as a child of the United States Air Force and moved every three years. I lived in England and Germany … and Nebraska. I happened to live a couple of places in the South — in Florida on Texas, not the Deep South — but my back-pedaling and explanation does no good with these so-sure so-smug Bostonians.

And perhaps they are right: once of the South, always of the South.

Maybe they mistake my Midwestern Nasal Twang for a southern accent. If I have a home, it’s Indiana, not the South.

But no, they tell me, I hear the South in you.

And it is of course nothing of which to be ashamed. It’s just that as a nomad, a constant traveler without a true home, it’s hard to claim an identity with the South, a place of such tradition and folly and majesty. It seems presumptuous of me to claim kinship with a land of such rich heritage. Us nomads know little of southern customs.

If I dissect my life, I realize I’ve spent most of it in portions of the South — Texas for three years, Florida for three years as a child and 24 as an adult, Kentucky (the northern South?) for five years.

And there is no doubt that the South — at the time I lived there and traveled through it — shaped me. My family’s epic migration from one end of the South to the other was a definining moment of my life, not just my childhood.

In the summer of 1965, when I was 10, my family moved from Miami to Fort Worth, Texas. It was a hell of a caravan: a moving van, two cars, five people and five dogs. My father and teen-age brother were up ahead in the Triumph, packed into the tiny sports car with all of the house plants healthy enough to make the trip. My mother, my 16-year-old sister Suzanne, five poodles and I followed in the Cadillac, trying to keep up with the little red car and managing our own internal crisis. I sprawled on the back seat with the four female poodles, all of whom were in heat. My mother and sister comforted the remaining poodle, Walter, up front.

It was August, and well over a hundred degrees. We managed, for the four days of that epic journey, to keep Walter away from the girls. At rest stops, my sister held Walter while I struggled like some low-budget Ben-Hur, with four females straining their leashes. Walter moaned and tugged at his collar. His teeth chattered like typewriter keys.

Picture the view from the back seat: There was my mother, driving, pretending not to notice my sister, who was riding shotgun. Though Suzanne was seated, she was moving, doing whatever dance was popular that summer. Music came in a steady beat from the AM radio – and what great music: Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” the Beatles’ “Ticket to Ride,” James Brown’s “Papa’s Got a Brand-New Bag.” There was also Herman’s Hermits’ “Henry the Eighth,” but still … if the summer of ’65 wasn’t the high water mark of rock’n’roll radio, then I’ll eat my Volkswagen.

That summer was kind of like the Continental Divide in popular music. We could look back one direction and see the matching suits, the well-scrubbed faces and the kind of rock and roll innocence we’d never see again. Looking the other way, we could see the patched jeans, the dope-smoking, the songs about war and injustice that would reach the top ten, and a weariness underneath the thrashing power chords. And they started calling it simply rock.

That was a great summer on the radio.

Now that all of that great music is playing in your head, think of poor Walter staring at the back seat mournfully, machine-gun fire emanating from his teeth, watching and waiting for the moment I would doze and he would make a move on the four females. But I was a determined guardian of doggie virtue.

And what song, of all the great songs on that radio that summer, was the soundtrack of Walter’s frustrations?

It was a song by England’s self-proclaimed “newest hitmakers” that twanged out nearly every hour on the hour. As Suzanne writhed in the front seat and my mother pretended to passing motorists that she didn’t notice her daughter’s seizures, Walter gazed longingly at four sets of nubile poodle thighs, and an adenoidal wail blared from the tinny speakers, voicing the hound’s lament:

I … can’t … get no …

I … can’t … get no

No sat-iss-fack-shun

Over the years, when American mothers and fathers feared for the well-being of their children and regarded Michael Phillip Jagger as rock and roll Lucifer, corrupter of youth, leading the nation’s children down the path toward carnalities too bizarre to imagine, I could never see the grounds for their fears. Whenever vice-presidents or members of congress (or their spouses) prated about pop-music vulgarity and lascivious lyrics, they offered as evidence the Jagger-Richards song catalog.

When others conjured visions of evil too horrifying to mention, all the fault of the Rolling Stones, all I could think of was that horny poodle with the chattering teeth.

In spite of the poor dog’s frustration, that trip remains one of my favorite memories of childhood and, like so much of my life, it is informed by rock and roll. It’s as if my whole life has a soundtrack played by two guitars, bass and drums.

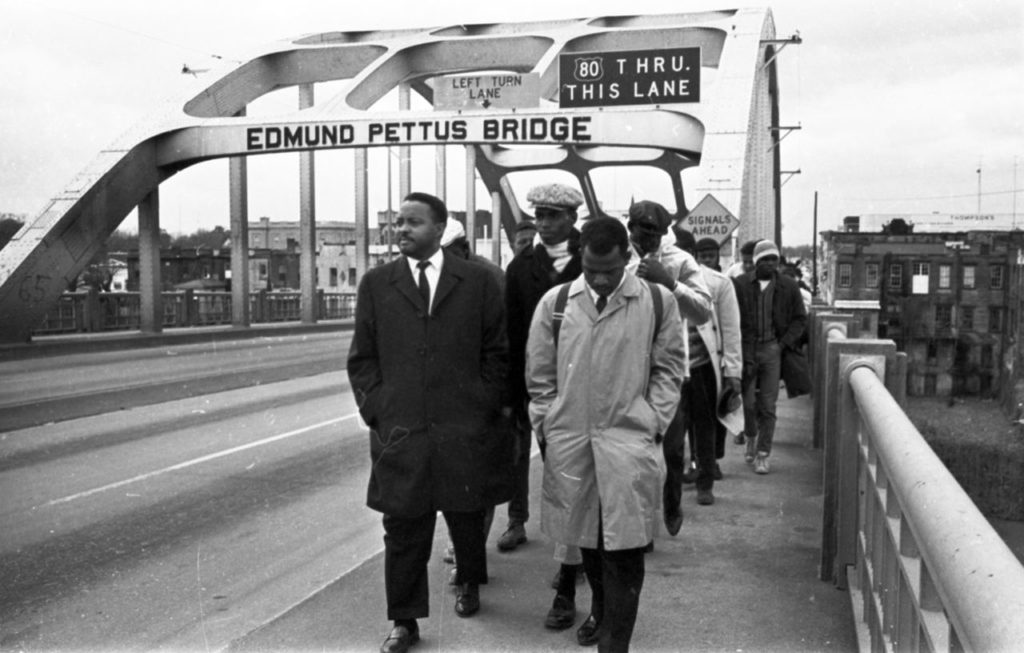

But that summer was far more memorable — and historic — for other reasons. That summer, we drove through the heart of the South, up through Georgia and across Alabama, right through Selma, and across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which four months before had been the site of one of the bloodiest confrontations in America’s war for civil rights.

Looking back, I see that I was a strange boy in lots of ways. I’d developed the habit of reading newspapers — the local daily for the last three years had been the Miami Herald, but my father also had next-day delivery of the Chicago Tribune and we got the National Observer weekly. I was also a regular viewer of nighly news programs — we were a Huntley-Brinkley house, though I’d occasionally get to see Walter Cronkite. We were a news-obsessed family. The dinner table discussion was often about the news. The news was often on during dinner.

So even as a kid trapped in the backseat with four dogs in heat, I knew the importance of where we were when he drove into Selma. I remember the silence. Suzanne turned off the radio for the only time I remember on the trip. “This is it,” I heard her whisper, and our radials reverently crept over the bridge. It was so quiet. Did we think we would wake the ghosts of Bloody Sunday? Up ahead, my father and brother crept along in the Triumph at motorcade pace.

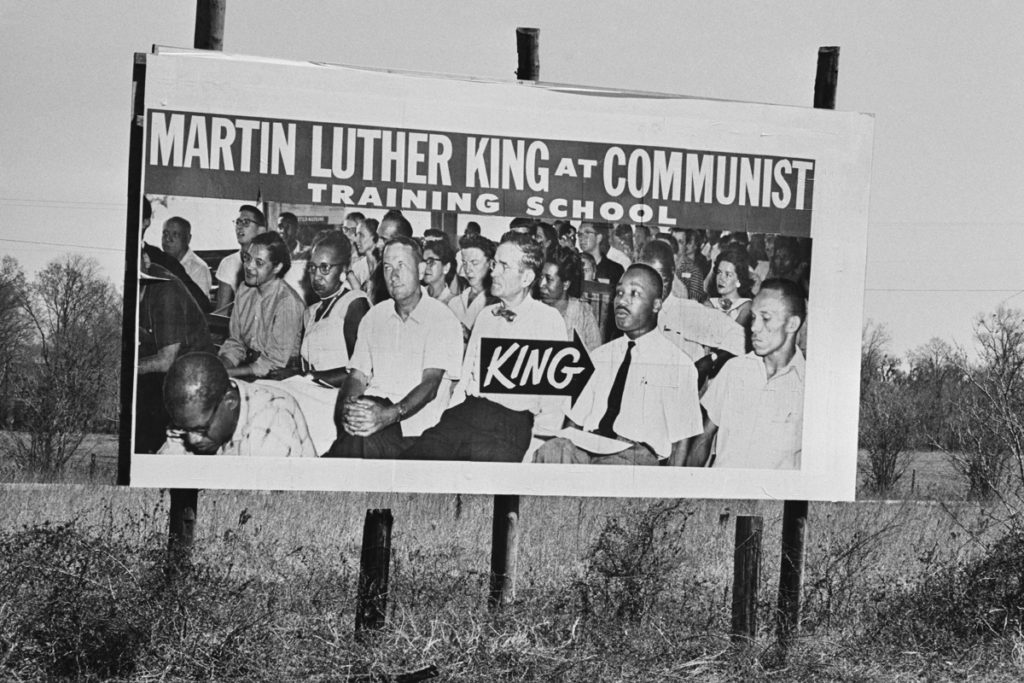

To that point, I had been denied — spared is most like it — one of the defining experiences of the South: segregation. The military maintained its own schol system for service children. My classmates and our neighbors were fully integrated. I had trouble reconciling the reality I saw on the Air Force base with the pictures we saw from out there, in the civilian world. The integrated world of the military base on which we lived was so foreign from the black-and-white footage we’d seen from Selma or from the fire hoses that pelted the street protesters in Birmingham.

I had been protected from the black-and-white world we saw from the kitchen table, but now that was about to end.