Monologues with the Maestro

by William McKeen

Copyright © 2023

Novelist Ernest Hemingway, winner of the Nobel Prize for literature, began his writing career as a journalist and continued writing nonfiction — dispatches, long-form pieces and memoir — for the rest of his career. Though he occasionally made derisive comments about journalism and its practitioners, he also acknowledged the role his reporting played in forging his distinctive and oft-imitated style.

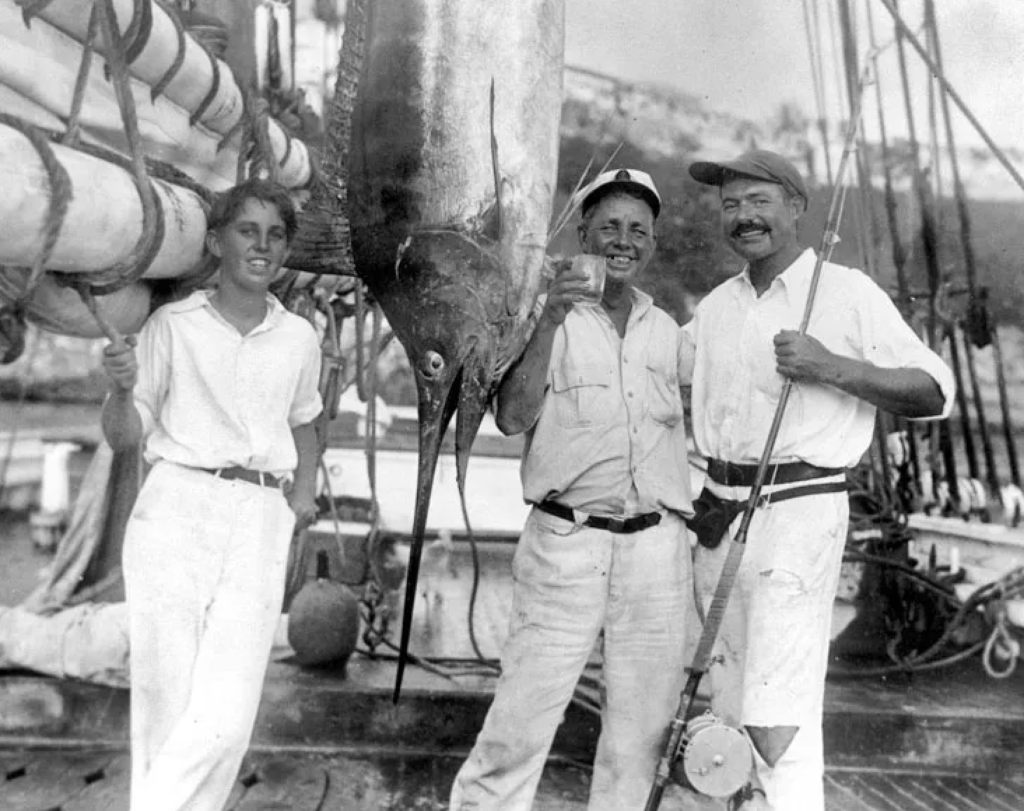

Born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, Ernest Miller Hemingway was the son of a physician, Clarence Hemingway, and Grace Hemingway. He was the second of six children and grew up as the only male child until his brother was born 16 years later. He was thus his father’s companion on regular hunting and fishing trips to Michigan, adventures which fed some of his early short stories.

He worked on his high school newspaper and yearbook, which gave him a taste for journalism. After graduation, he sought escape from his suburban life with his parents and went to work for the Kansas City Star, where he was swaddled in the practices of professional journalism.

He looked to the Star as a way of furthering his education. As biographer Carlos Baker wrote, “He counted on the Star to polish his prose and on Kansas City to educate him in the seamier sides of human experience.” The inverted-pyramid style — which began to develop during the Civil War and which required that the most important elements appear first in the story — was taught by the Star’s editors and Hemingway was a quick learner. He cited the Star’s terse style guide for reporters as a lifetime influence on his writing. He followed the guide’s instruction to write using short vivid sentences and to omit superfluous details.

He left the job after six months to enlist as an ambulance driver during the First World War. After two months in Italy, he was injured in a mortar attack, and hospitalized, recovering from injuries so serious that doctors considered amputating his leg. Back home, he found that his war experiences created a gulf between himself and his parents and left home for a job in Toronto, before returning to Chicago.

But while in Canada, he had made an alliance with the Toronto Star, and was summoned to return to journalism. Soon after his marriage to Hadley Richardson, he returned to Europe as the Paris correspondent for the Toronto Star Weekly.

As European correspondent, Hemingway proved himself as a reporter, covering war in Greece and witnessing the incineration of Smyrna. He covered hard-news stories, but also published comic tales of the French for the amusement of Canadian readers.

Here he strayed a bit from the rigors of the style drilled into him by the Kansas City editors. He became part of the expatriate literary crowd — Ford Maddox Ford, James Joyce, Scott Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein — and so he wanted his writing to rise above the conventions of everyday journalism. He developed a dry, comic style for his lifestyle pieces about Europeans.

Soon he began to pursue a more literary career, publishing a chapbook of poetry and a slim volume of stories with a lower-case title, in our time. Fitzgerald became his champion and recommended Hemingway to Charles Scribner, who had published Fitzgerald’s first novel, This Side of Paradise. Fitzgerald held a lot of promise for Scribner, so he listened and by 1926, Hemingway had joined Fitzgerald as a Scribner author, working with gifted editor Maxwell Perkins (who would also guide Thomas Wolfe and James Jones). Hemingway’s first novel, The Torrents of Spring, was a minor work, but later that year, The Sun Also Rises, his first major novel, appeared.

Hemingway began to publish his novels and story collections that comprised one of the most significant bibliographies of 20th Century American Literature. After The Sun Also Rises came A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea. But despite those occasional derisive comments about journalism, Hemingway never fully left non-fiction — or rather his personalized version journalism — behind.

He published his second major novel, A Farewell to Arms, in 1929, but then came his first two book-length nonfiction: Death in the Afternoon in 1932 and Green Hills of Africa in 1935. Both were memoirs concerning two of his major occupations: bullfighting and hunting.

He had written about Spain before, in The Sun Also Rises. That was also when Hemingway fell in love with bullfighting. By the time of Death in the Afternoon, six years later, he was an evangelist for the sport and it served as his treatise on its history and what he saw as the beauty of the sport. Green Hills of Africa told of a safari with Paulette, his second wife, that served as much as a seminar on world literature as much as a hunting expedition.

Stalking wild beasts was interrupted by lectures on reading and writing. In one of his soliloquies, Hemingway delivers his famous comment on the writing from his home country, that modern American literature was derived from Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. The quality of the reporting was discounted by some critics, one of whom — in the New York Times — said that all of the real people quoted in the book sounded like characters in a Hemingway novel. Neither was considered a major work at the time, nor in later critical assessment.

Simultaneously with those books, Hemingway began contributing his personal reportage to Esquire, a new magazine founded by Arnold Gingrich. As Baker wrote in his Hemingway biography, “The magazine would attempt to do for American men what Vogue was doing for American women.”

Hemingway’s celebrity was such that he could write about nearly anything in his life and there would be an audience for it, particularly in this new men’s publication. Gingrich. urged him to stick to stories of hunting and fishing, in line with the testosterone theme of the magazine. The “letters” (as they were called) were often like diary entries.

One of the most successful of these pieces was “Monologue to the Maestro,” in which a young acolyte from Minnesota — dubbed the Maestro because he plays violin — treks to Key West to sit at Hemingway’s feet to learn about Writing. It’s comic, but it also contains a telling comment when the protege asks the older (all of 35 at that point) writer about the uses of imagination in writing. What, the Maestro wants to know, differentiates serious writing from mere reporting? “If it was reporting,” Hemingway lectures, “they would not remember it.”

He tells the Maestro that what makes writing live is the ability to describe action and events in such a way that readers then visualize what the writer is describing, becoming a collaborator in the storytelling. The reader’s imagination, Hemingway lectures, will complete the picture. The element of immediacy – vital to daily reporting – is soon lost and in order for a piece of writing to endure, it must be “round and whole and solid,” as Hemingway says.

Even when he was ostensibly back in the world of reporting, he was stalked by his image and celebrity. Case in point: Hemingway’s coverage of the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance. By the time he left for Spain as a correspondent in 1938, Hemingway had made it clear that he would not be an impartial reporter. He had signed on to produce a documentary to raise money for the cause of the rebellious peasants.

The news agency clearly hired him for his star power. By the time of the war in Spain, Hemingway was already a popular novelist, having published The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms. But his journalistic credibility was compromised by his role as a fund-raiser for one of the warring sides in the conflict.

Hemingway’s fiction had by that time showed itself to be obsessed with evidence of masculinity, with laconic, aloof and heroic protagonists. He had created and image and his I-was-there reporting style watered and manured that image.

His reporting from Spain seemed to require that he emphasize his closeness to danger. There’s a good example of this in “A New Kind of War,” North American Newspaper Alliance dispatch, April 14, 1937. Hemingway writes in direct address, a style he often employed. He puts the reader in bed, listening to rifle fire all night long, and then the horrifying sound of an approaching mortar. Having survived the night, Hemingway – and, by address, the reader – takes solace in survival. Unfortunately, Hemingway clumsily imitates the sound of gunfire – rong, cararong, rong rong. It’s jarring and unintentionally comical.

Aside from providing a cautionary tale about how not to use sound effects, the dispatch is notable for Hemingway’s need to place himself at the center of his story. He was coming off a decade-and-change of celebrity and knew that he was his own best character, that what sold his stories to readers was his fame and his image as the most masculine of men, nonchalant in the face of death.

Continuing, in that same dispatch, Hemingway recounts strolling down to the square, outside the hotel, and inquiring about the dead and wounded. He’s still in his bathroom and bedroom slippers when he witnesses a police officer covering up a torso separated from his head. He is immediately seized with thoughts of breakfast. Hemingway’s reporting is fecund with macho.

Much of his reporting from Spain emphasizes his proximity to battle, as if needing to prove his manly credentials. Others would be taken aback by the horror just described; to him, it’s a brief episode before breakfast. He opens another war dispatch with further accounts of gunfire, noting that if one hears the sound of a bullet, it’s too late because “if you hear them, they are already past.”

Other dispatches continued to craft his persona as a celebrity journalist. His finest writing about the Spanish Civil War was not found in his journalism but in his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Much like one of his devoted acolytes later in the 20th Century — Hunter S. Thompson — his fame as a journalist became so great that he was unable to function as a reporter.

Thompson like Hemingway before him became more famous than the people he covered. Thompson dealt with this by turning every piece he wrote into an exercise in process. No matter what he was assigned to cover, he wrote about Hunter Thompson trying to write an article, creating a form of metajournalism.

Metajournalism didn’t originate with Thompson. A few years before Thompson’s arrival in the national consciousness, Terry Southern published a work of journalism about journalism called “Twirling at Ole Miss” in Esquire in 1962.

But when both those younger writers were still in knee-pants, Hemingway used his celebrity as a central feature of his journalism. His stories from Spain often delve into his gathering of information, allowing readers to see the under-the-surface levels of his storytelling.

He carried his notoriety as Marley’s Ghost bore his chains.

In fiction, Hemingway was minimalist, but in journalism was verbose, often with superfluous detail.

In his journalism, Hemingway often resorted to direct-address. At times, this felt as if he was a patient parent explaining a story to a child. Even in his dispatches from the Second World War, he resorts to the explanatory tone and shows that editors were reluctant to edit a celebrity correspondent.

Hemingway survived two plane crashes in two days during the period he was covering the war, which he did for the experimental no-ads-allowed newspaper PM early in the war and for Collier’s later in the war.

He returned to journalism in his last years to write “The Dangerous Summer,” a series for Life magazine about the son of the bullfighter who had inspired a character three decades before in The Sun Also Rises. Hemingway produced a huge manuscript, which the editors spread over three issues. It was not published in book form for a quarter century.

A Moveable Feast (1964), his memoir of Paris in the 1920s, was filled with stories of his colleagues Fitzgerald, Stein and others. A collection of his journalism dating from Toronto Star days, Byline, appeared in 1967. A later collection, Dateline: Toronto (1985), collected previously unpublished pieces. Under Kilimanjaro (2005), though a memoir, was the complete manuscript of a book that had been published in 1999 as a novel, True at First Light.

He was married four times — three times to journalists: Pauline Pfeiffer worked for Vogue in Paris, Martha Gellhorn was a celebrated war correspondent, and Mary Welsh, whom he met in London while they were both covering the Second World War. He had three sons: John, known as Jack, with first wife Hadley Richardson; and Patrick and Gregory, with Pauline Pfeiffer.

His most fecund years were in Key West, where he finished A Farewell to Arms and wrote most of For Whom the Bell Tolls. In the decade between the appearance of those books, he published those two nonfiction works mentioned earlier (Death in the Afternoon and Green Hills of Africa), a novella (To Have and Have Not) and two story collections (Winner Take Nothing and The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories, which also contained the script for a play). He produced two documentaries about the war in Spain intended to raise money for the revolutionaries. This is also the era when he contributed regularly for Esquire. He was remarkably productive, yet also maintained an active life as a sportsman and tavern raconteur. He made friends with fishermen, handymen and others, reveling in the live-and-let-live ethos of the village at the end of the road.

He later moved to Cuba but left for his final home, in Idaho, in 1959. It was there, in the village of Ketchum, where he took his life by gunshot on July 2, 1961.

Nonfiction Works by Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway, Ernest. Death in the Afternoon. New York: Scribner, 1932.

_____. Green Hills of Africa. New York: Scribner, 1935.

_____. A Movable Feast. New York: Scribner, 1964.

_____. Byline: Ernest Hemingway. Edited by William H. White. New York: Scribner, 1967.

_____. Ernest Hemingway, Cub Reporter. Edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1970.

_____. The Dangerous Summer. New York: Scribner, 1985.

_____. Dateline: Toronto. Edited by William H. White. New York: Scribner, 1985.

_____. Under Kilimanjaro. Edited by Robert W. Lewis and Robert E. Fleming. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2005.

Works About Ernest Hemingway

Baker, Carlos. Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Scribner, 1968.

Bradford, Richard. The Man Who Wasn’t There: A Life of Ernest Hemingway. New York: Tauris, 2019.

Dearborn, Mary V. Ernest Hemingway: A Biography. New York: Knopf, 2017.

Hemingway, Gregory. Papa: A Personal Memoir. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

Hemingway, Mary Welsh. How It Was. New York: Knopf, 1976.

Hotchner, A.E. Papa Hemingway. New York: Random House, 1966

Reynolds, Michael. The Young Hemingway. Oxford, England: Blackwell, 1986.

_____. Hemingway: The Paris Years. Oxford, England: Blackwell, 1989. • . Hemingway: The 1930s. New York: Norton, 1997.

_____.Hemingway: The Final Years. New York: Norton, 1999.

Ross, Lillian. Portrait of Hemingway. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1961.

Rovit, Earl. Ernest Hemingway. [Revised edition] Boston: Twayne, 1986.