Clarity Amid Chaos

by William McKeen

Copyright © 2023

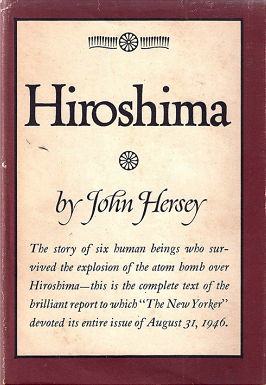

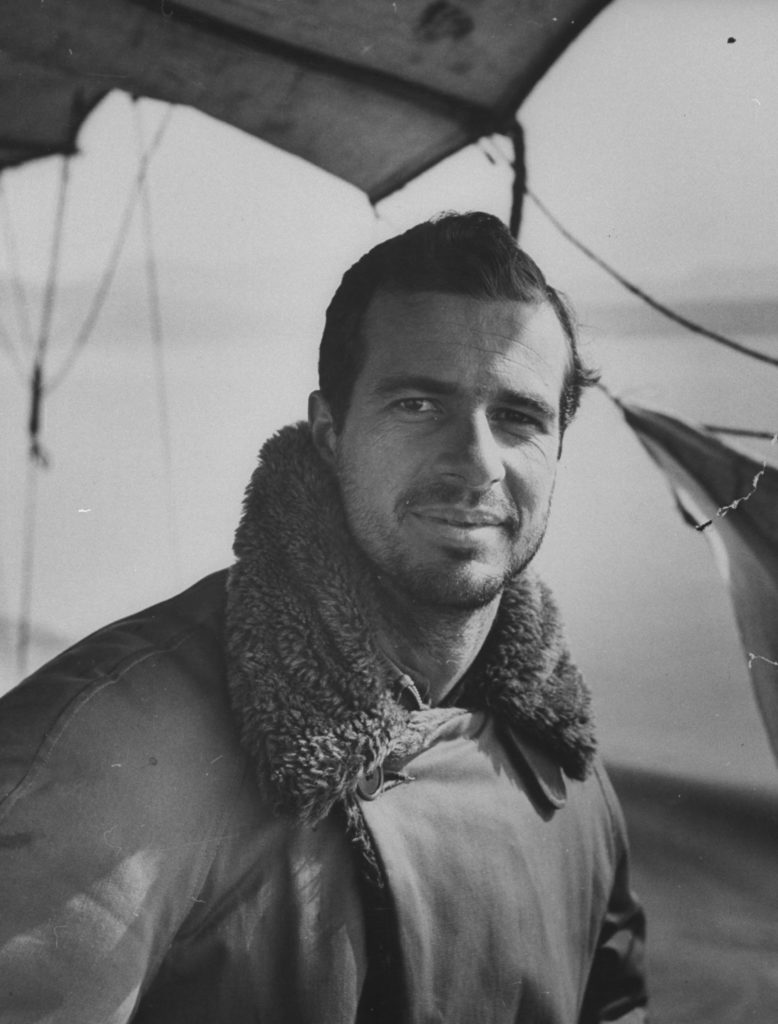

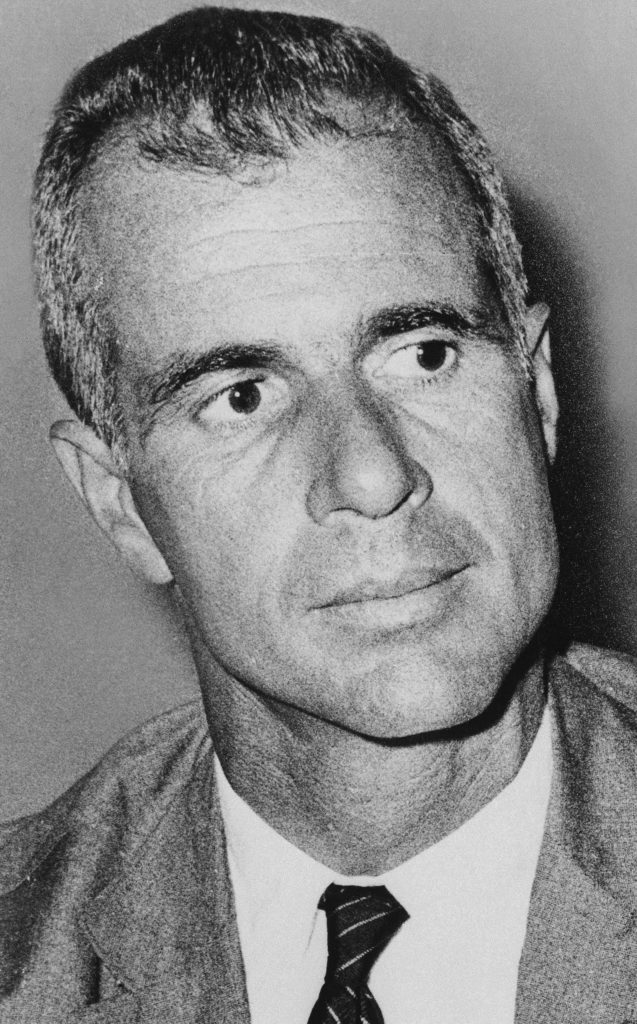

Reporter and novelist John Hersey created Hiroshima (New York: Knopf, 1946), cited as the greatest work of American journalism in the 20th Century. The book was a harbinger of the “new journalism” explosion of the 1960s, yet within a few years Hersey become a critic of the form. A prolific writer, his fiction and nonfiction were driven by a concern for social justice, and he served as one of the greatest practitioners and the brooding conscience of the literary journalism movement he helped inspire.

Born in 1914 in Tientsin, China, John Richard Hersey was the son of American missionaries Roscoe and Grace Hersey, who were posted overseas by the YMCA. John Hersey spent his early years in China but when he was 10 he returned to the States with his parents, to Westchester County, New York. He finished his secondary education at Hotchkiss School in Connecticut, then enrolled at Yale University.

At Yale, Hersey made the football squad and future president Gerald Ford was a teammate. Hersey also worked on The Yale Daily News and was a member of the secret society, Skull and Bones. As was the case for any Yale student who distinguished himself at the Daily News in that era, Hersey was offered summer work at Time magazine while still in college. Henry Luce, founder of the Time-Life empire, had a nearly identical life to Hersey’s — born to American missionaries in China, Luce’s educational and career path followed the same trajectory, a quarter century before. At Yale, Luce had worked alongside classmate Briton Hadden at the Daily News and they partnered to create Time magazine in 1923. A decade later, Hadden was dead and Luce had turned the company he started with a classmate into an empire that included Fortune and Life magazines.

Luce regarded Hersey as something of a protege, but Hersey and Luce diverged radically on politics. Luce’s inherent conservatism was offensive to Hersey, who bespoke classic liberal values. At first, Hersey resisted Luce’s efforts to bring him into the Time-Life fold. After college graduation in 1936, Hersey studied at Cambridge for a year, then returned home to become personal secretary to Sinclair Lewis, the first American writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Working for Lewis was a trial. The elder writer was in decline, and his early triumphs, including Main Street (1920) and Babbitt (1922), were in the rear-view mirror. His writing was skidding downhill and Lewis often was drunk. Hersey’s duties included mixing drinks and driving for the old man. Yet there was value in this difficult apprenticeship. “I was exposed to someone who lived for his writing,” he told an interviewer in The Paris Review.

Eventually, Hersey joined Time magazine, where his dispatches were printed without his byline, which was the magazine’s style. The magazine’s prospectus had vowed that the contents would appear to readers as if written by one person, for one person. There was no room for a writer’s voice or ego. This meant that Hersey and other reporters for the magazine were subject to the editing of Whitaker Chambers, whose position at the magazine gave him license to revise the copy of liberal reporters to reflect Luce’s conservative worldview.

In 1940, Hersey married Frances Ann Cannon, whose previous suitor had been John F. Kennedy, giving the writer another close encounter with a future president.

Posted in Asia as the Second World War began, Hersey’s ambition to write substantive nonfiction surfaced with his first two books of reportage, Men on Bataan (New York: Knopf, 1942) and Into the Valley (New York: Knopf, 1943), which was a hybrid of reporting and memoir. Written while employed by Time, Hersey worked herculean hours to make publishing deadlines. The stateside audience sought stories from Bataan and Guadalcanal — though fellow journalist Richard Tregaskis beat Hersey to the publishing punch; Guadalcanal Diary (New York: Random House, 1943) came out nearly a month before Into the Valley.

Eager to serve his country, Hersey was disappointed that the only commission offered him by the United States Navy was for a public-relations position. It was pointed out that Hersey could best serve his country by covering the war. He chose to follow that advice.

Both of Hersey’s books had been best-sellers and he and Frances had two children, which caused future President Kennedy to whine. “He’s sitting on top of the world at this point,” he wrote his sister, noting that Hersey had “a best seller — my girl, two kids — big man on Time — while I’m the one that’s down in the God damned valley.”

After a return to the states, Hersey was deployed to the European theater by Time and covered the assault on Italy. This time, he produced a work more substantial than his slim nonfiction books from the Pacific. As he reported for the magazine, he felt a growing fictional narrative inside drawn from his experiences. He produced A Bell for Adano (New York: Knopf, 1944) quickly, producing what critic Diana Trilling called “our first fiction of the American government of Italy.” Janet Flanner, The New Yorker’s Paris correspondent, wrote him a complimentary note: “To have turned reality into fiction, in form, demonstrates your talent and heart.”

The book was soon adapted for the Broadway stage and for film. Celebrated journalist Damon Runyon, then hospitalized and silenced by throat cancer, passed a note to one of his bedside visitors, New York Post columnist Leonard Lyons. “Do you know Hersey?” Runyon wrote. “He is the best writer that has come out of the war so far.”

Hersey’s reputation was growing and the warm reception for his first novel — which would win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1945 — made him ponder his future in journalism. He was with Time, of course, and was being courted by The Saturday Evening Post. But if he wanted to write journalism and build a literary reputation, the publication that made the most sense for a professional alliance was The New Yorker.

Luce was dangling the prospect of a major job — maybe even the top job — at Time. Ben Hibbs, editor of the Post, wined and dined the writer and his wife. But it was Hersey’s experience working with the celebrated editors at The New Yorker that helped make up his mind.

Hersey and his bride met with her old boyfriend, Jack Kennedy, in New York. Kennedy was back from the Pacific, where he’d lost his command, PT-109, one of the small wooden patrol-torpedo (hence PT) boats in the South Pacific. Kennedy’s craft was sunk, and he and his crew had made it to a nearby island, Kennedy towing an injured crewman using a rope through his teeth. It was a three-mile swim in treacherous water and, sitting in a New York nightclub months later with Hersey and his former girlfriend, he shrugged off the accomplishment. Hersey, however, smelled a story. Kennedy was embarrassed by the episode — he’d lost his boat, after all — but was willing to talk to Hersey for a story, as long as the reporter talked to all of the other survivors to get a fuller picture. Hersey tracked down the crew and got the story but found Time magazine disinterested. Hersey had earlier done a feature for Life about PT boats and Luce wanted something new.

So Hersey took the story to The New Yorker. One of its top editors, William Shawn, had been at the nightclub when Kennedy first unfurled the story to Hersey. Shawn impressed Hersey with his meticulous editing of “Survival,” as the story was titled in the magazine. Not long afterward, when John Kennedy’s older brother Joseph Jr. was killed in a plane crash, father Joe, the family patriarch, seized upon “Survival” as the foundation for the hero-narrative that would lead his second son to the White House.

The experience working with such precise and careful professionals as Shawn and New Yorker founding editor Harold Ross so impressed Hersey that he determined that magazine would be his new home. He withdrew from an exclusive relationship with Time-Life and foresaw a future as a novelist with ties to America’s pre-eminent literary magazine.

The war ended in Europe and then in the Pacific, after the annihilation of two Japanese cities in August 1945. From the moment Hersey learned the horrifying news, he knew he wanted to write about the devastation. Though he still felt an allegiance to Time-Life and all that Luce had done for him, he knew that whatever he wrote about the use of atomic weapons for Time, the editors would pervert his article into a testament of American might. Telling this story for The New Yorker made more sense. Luce put the full-court press on his protege, telling Hersey it was time for him to step into management. To Hersey, of course, this made so sense, as he was becoming recognized not just as a journalist but as a literary figure. Nonetheless, Luce agreed to co-finance (with The New Yorker) a Hersey trip to China and Japan, sneering at The New Yorker all the while.

To make himself morally and contractually free, Hersey resigned from Time-Life immediately after the war ended, but there was an understanding that he would remain a contributor. Indeed, from China he filed stories for both magazines. But he was on a trajectory for Japan and the aftermath of the bombing.

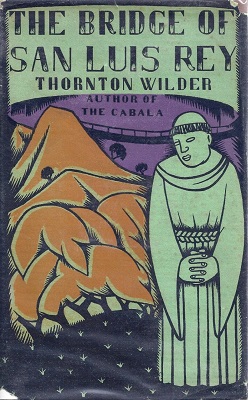

On the journey from China to Japan, Hersey read Thornton Wilder’s novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1927). It told of six people, five of who are killed when a rope bridge in the Andes collapses in 1714. The characters are all connected in some way. The sixth character, a priest, sees the tragedy and is left to muse on the nature of a God who would allow such a thing to happen. Hersey claimed that Wilder’s book gave him the narrative structure he would use for the story he had not yet reported, the story of Hiroshima survivors.

He arrived in the decimated city in May 1946 and began interviewing somewhat indiscriminately. He needed the six characters, and the first people he found were the Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto and Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge, a Jesuit from Germany. These two clergymen led him to others who would become Hersey’s primary characters: a clerk, a widow and two physicians. Whether his characters were a good demographic representative of the survivors a was not the issue. They all had compelling stories.

In part to set up the drama — but also to fit into the methodical, slow-to-reveal style of The New Yorker — Hersey introduced them all in the first paragraph, dwelling on their names, not readily familiar to American readers: Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk; Masakazu Fuji, a physician; Hatsuyo Nakamura, a widow; Wilhelm Kleinsorge, a German priest; another physician, Terafumi Sasaki and Kiyoshi Tanimoto, a minister.

Already a novelist, Hersey knew how to build dramatic tension. After introducing his characters, he cross-cut between them as a screenwriter would, building tension. Though he was describing the most chaotic moments in human history, he wrote with detachment. Instead of instructing readers how to feel about the death and destruction, he presented the narrative in clinical language. He wrote of horrific events — of flesh slipping off of bone, of humans vaporizing … just disappearing — and yet never once did the language rise to the level of hysteria. His goal was not to insulate readers by feeling for them, but in forcing them to feel. Paradigms seemed to present themselves. For example: Miss Sasaki, the clerk, is saved when she turns her head from the window at the moment of the bomb’s noiseless flash. She is thrown to the floor and a bookcase collapses on top of her. To conclude the opening portion of the narrative, he presents the young woman’s plight to demonstrate the realities of the world that has just irrevocably changed. The bookcase right behind Ms. Sasaki collapses on top of her, horribly twisting her leg. The irony is not lost on Hersey. As he wrote at the end of the first segment of Hiroshima: “There, in the tin factory, in the first moment of the atomic age, a human being was being crushed by books.”

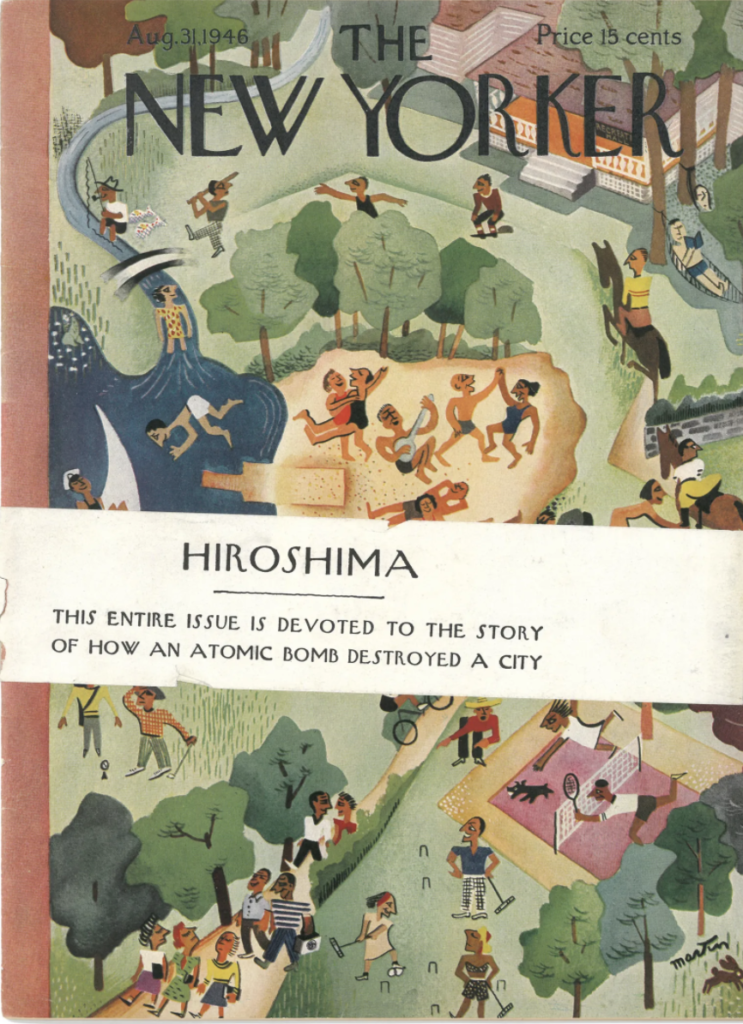

Hersey wrote quickly, starting on the manuscript while returning from Japan by steamer. The New Yorker editors realized that to serialize the work might dilute its impact or trivialize it, shoehorning it into the magazine with its regular fare. Ross and Shawn decided to make it the entire editorial content of the magazine’s August 24, 1946 issue. It was published in book form that fall by Alfred A. Knopf and has never been out of print.

In 1999, New York University polled historians, educators and journalists and the conclusion was that Hiroshima by John Hersey was the greatest work of journalism in the 20th Century.

Hersey began a long and prolific career as a novelist. He revisited the key elements of his life, including the Second World War — The Wall (Knopf, 1950), about the Warsaw Ghetto; The War Lover (Knopf, 1959), about a pilot who thirsts for battle — the role of American missionaries in The Call (Knopf, 1985); and relations with Asia in A Single Pebble (Knopf, 1956) and White Lotus (Knopf, 1965). His occasional forays into journalism included Aspects of the Presidency (Knopf, 1980), in which Gerald Ford, his former football teammate, gave him unprecedented access to the White House.

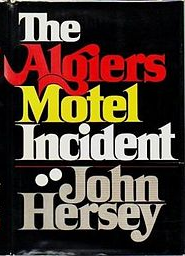

His other major work of journalism was The Algiers Motel Incident (Knopf, 1968), which was — to borrow a marketing phrase from Truman Capote — a “nonfiction novel” about the killing of three young people during racially-charged riot in Detroit in 1967. Unlike Hiroshima, Hersey did not withhold his feelings about the injustice in the story and the killings, carried out by police.

With Hiroshima, Hersey had created a template for the “new journalism” (or literary journalism) revolution that would be inaugurated in the 1960s. However, at the end of that decade, he felt that too many writers had played fast and loose with the facts. In “The Legend on the License,” which appeared in The Yale Review in 1986, Hersey took many practitioners of literary journalism to task — primarily Tom Wolfe, whose book on the space program, The Right Stuff (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979), had irked Hersey with its errors and inventions. The legend on the license — the imaginary license borne by journalists — was that “none of this is made up.” Hersey thought his descendants had gone too far.

Hersey divorced his first wife in 1958 and married Barbara Day Addams the following year. In addition to his writing career, he served as master of Pierson College at Yale and had five children.

He died March 24, 1993, in Key West, Florida. He is buried on Martha’s Vineyard.

Nonfiction Works by John Hersey

Hersey, John. Men on Bataan. New York: Knopf, 1942,

_____. Into the Valley. New York: Knopf, 1943.

_____. Hiroshima. New York: Knopf, 1946. [New edition with additional chapter, 1985]

_____. Here to Stay. New York: Knopf, 1963.

_____. The Algiers Motel Incident. New York: Knopf, 1968.

_____. Letter to the Alumni. New York: Knopf, 1970.

_____. Aspects of the Presidency. New York: Knopf, 1980.

_____. Life Sketches. New York: Knopf, 1989.

About John Hersey

Blume, Lesley L. L. Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2020

Lemann, Nicholas. “John Hersey and the Art of Fact,” The New Yorker, April 29, 2019

Sanders, David. John Hersey Revisited. Boston: Twayne, 1991.

_____. John Hersey. Boston: Twayne, 1967.

Treglown, Jeremy. Mr. Straight Arrow: The Career of John Hersey, Author of Hiroshima. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019