The Prince of Gonzo

by William McKeen

Copyright © 2023

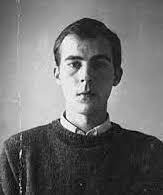

Hunter S. Thompson arrived in Louisville, Kentucky, the same time as the devastating flood of 1937. Unlike the flood waters, Thompson never receded and remained after his death a force in American letters — at least in the nonfiction division.

Thompson’s literary creation, known as gonzo journalism, endured despite attempts by other writers to dilute its style and voice with imitation. Though many tried to define gonzo, it is best described as whatever Hunter Thompson wrote.

Thompson was the eldest of three sons of Jack and Virginia Thompson. His father was older and on his second marriage (there was a child from the first, but he remained distant from his younger half siblings) and was not the sort of young hands-on father that young Thompson saw guiding his childhood pals. Jack Thompson was an insurance salesman, chain-smoker and observer of his son’s life, not a participant. He was soon dead and young Thompson’s mother, a researcher at Louisville Free Public Library, retreated into a haze of alcoholism as her eldest son ran roughshod.

Though firmly entrenched the city’s lower middle class, Thompson was the mascot of the city’s burgeoning social set. Louisville attracted new businesses in the post-Second World War era and the young executives raised their children in a cloistered society modeled on the classic rules of Southern civility and custom. The children, however, did not care for the genteel; they wanted to flirt with danger. This brought young ruffian Hunter Thompson into their circles, as a token bad boy. Thompson was thus ushered into the upper-crust Athenaeum Literary Society as a high school student. Just prior to graduation, however, he learned the realities of the haves and have nots. With two of his society friends, he attempted to rob two couples making out in a car in Louisville’s Cherokee Park. When charges were brought, the two other swains got them dropped, owing to their parents’ political connections. Absent such connections, Thompson was sentenced to 60 days in jail, missing the graduation ceremony.

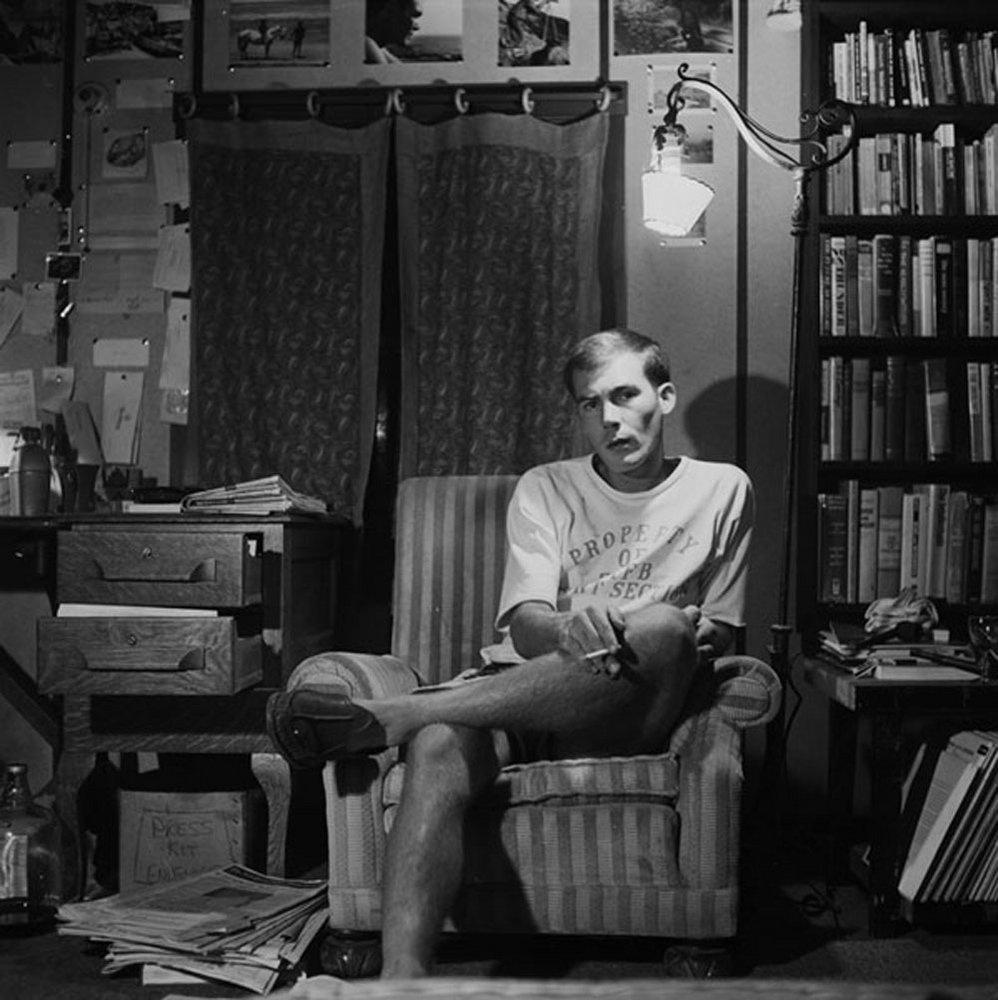

After jail, Thompson enlisted in the Air Force, he began his professional writing career as sports editor of the Command Courier at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida’s Panhandle. After leaving the service, he floated around the bowels of journalism at newspapers in rural Pennsylvania and upstate New York. These jobs were all short-term and filled with drama. He left one job after wrecking a colleague’s car. At another newspaper, he was let go for destroying a vending machine. Thus unemployed, he lived in upstate New York with friends and in an abandoned, unheated cabin, vowing to become a writer “until the dark thumb of fate” crushed him into nothingness.

He drifted through the Caribbean and South America, eventually finding the freelance role worked well for him. Considering his unorthodox style, his venue was a mismatch: The National Observer, conceived as the Sunday edition of The Wall Street Journal. But Thompson’s honest prose and his ability to find unusual stories everywhere caught the eye of an editor who encouraged the young writer to deliver literate, personal narratives of a fish out of water.

Back in the states, however, he thought it best to keep his distance from the cubicled office and, with his new wife, Sandra Dawn, he ended up in San Francisco as the Observer correspondent for the birth of the counter culture in the mid-1960s. A disagreement with editors soon ended his relationship with the Observer and his main contribution to his family’s income came from donating blood. He did get an assignment to do apiece on the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang for The Nation. He introduced himself to the Angels — which no previous reporter had done — and wrote a piece called “Losers and Outsiders” that brought a lot of attention when it appeared. Soon, Thompson’s mailbox was stuffed with offers from publishers who wanted him to expand the article into a book. A self-described lazy hillbilly, he chose to go with Ballantine, which wanted a paperback original. It didn’t require a prospectus or other examples of salesmanship the other publishers asked for.

Thompson rode with the motorcycle gang for a year, though not on a Harley Davidson. He trailed them in his Rambler, observed their lifestyle and earned their confidence. Eventually, however, they turned on Thompson and beat him. Angels leader Sonny Barger maintained that Thompson provoked the beating in order to give himself an ending for his book. By the time the book was published, Ballantine’s editors considered it too good to be a paperback original, and it was published in hardcover — Hell’s Angels (Random House, 1967).

The editors wanted something else from Thompson and he sold them on the concept on a book about the “death of the American Dream.” But after three years of research, he was unable to come to terms with the ponderous project. He did find his distinctive style while ripping through a series of pay-the-bills assignments for small magazines. In one of the pieces, he described his homecoming to Louisville for the Kentucky Derby and ended up giving editors his unedited notes to complete the story. When the magazine published this straight-from-the-brain prose, it was hailed as the next step in the evolution of journalism. A friend of Hunter’s called it “gonzo.”

Thompson and his wife and son had moved to Woody Creek, Colorado, outside of Aspen, and he ran for county sheriff. He sought out Rolling Stone magazine, in San Francisco, to publish a story about his campaign for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado. He ran on the Freak Power ticket, an effort by Aspen-based hippies to take control of their community. Hair was a political statement then, and so while running against the crew-cut incumbent sheriff, Thompson shaved his head so he could refer to “my long-haired opponent.”

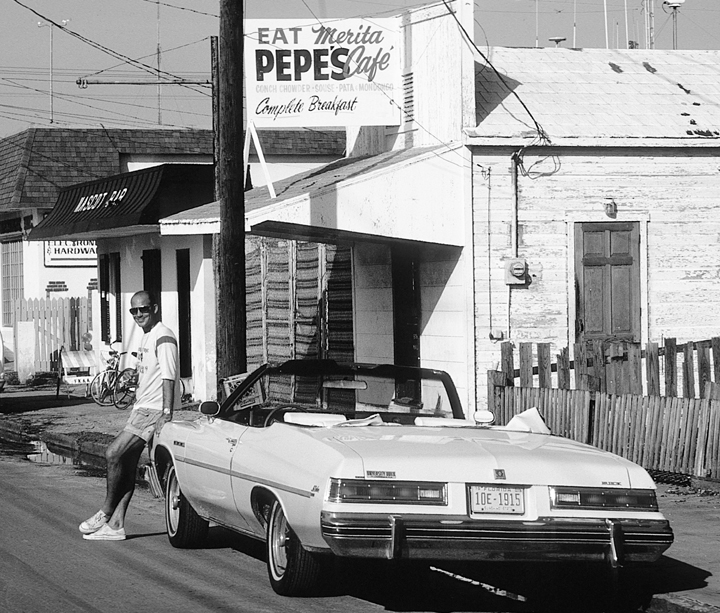

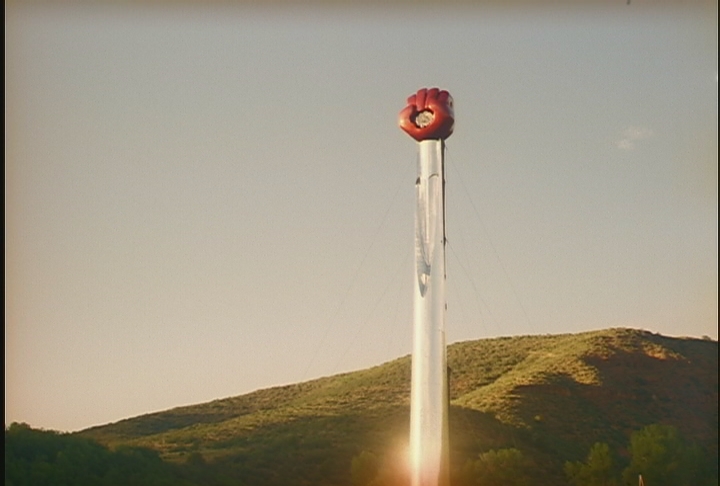

Photo by Tom Corcoran

Thompson lost the election, but he had made an important professional connection. The Rolling Stone alliance was a fourth-quarter effort to raise awareness of the Freak Power philosophy. The campaign failed, but thus began Thompson’s longest professional association, with Jann Wenner, founder and editor of Rolling Stone. The next year (1971), while doing a serious assignment on the murder of a Chicano reporter for the magazine, he interrupted his work to take his key source to Las Vegas to accompany him on his Sports Illustrated assignment to cover a motorcycle race. That aborted assignment led to Thompson’s creative nonfiction masterpiece, published in the magazine in November 1971. When it appeared in book form the next year — as Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Random House, 1972) — Thompson was in the middle of covering the presidential campaign for the magazine, resulting in Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72 (Straight Arrow, 1973).

Thompson’s utter revulsion for President Richard Nixon fueled some of his best work. He wrote that Nixon represented everything that was wrong with the country and his denunciations of Nixon fed some of his greatest work. When Nixon resigned, it appeared that Thompson’s muse had left him. His blessing-and-a-curse fame made it difficult to navigate the world as a reporter.

Thompson’s active career as a journalist was curtailed by his fame. When he attempted to cover the Senate hearings on Watergate in 1973 or the beginnings of the 1976 presidential campaign, he discovered that other journalists surrounded him, asking for autographs, making it impossible for him to work. He was also divorcing his wife and had discovering cocaine, the one drug that seemed to hamper his writing ability. He laid low for a few years, spending much of his time in Key West, and published little, other than his career omnibus, The Great Shark Hunt (Summit, 1979). A few years later, another attempt at recapturing his early fire — The Curse of Lono (Bantam, 1983) — fell flat.

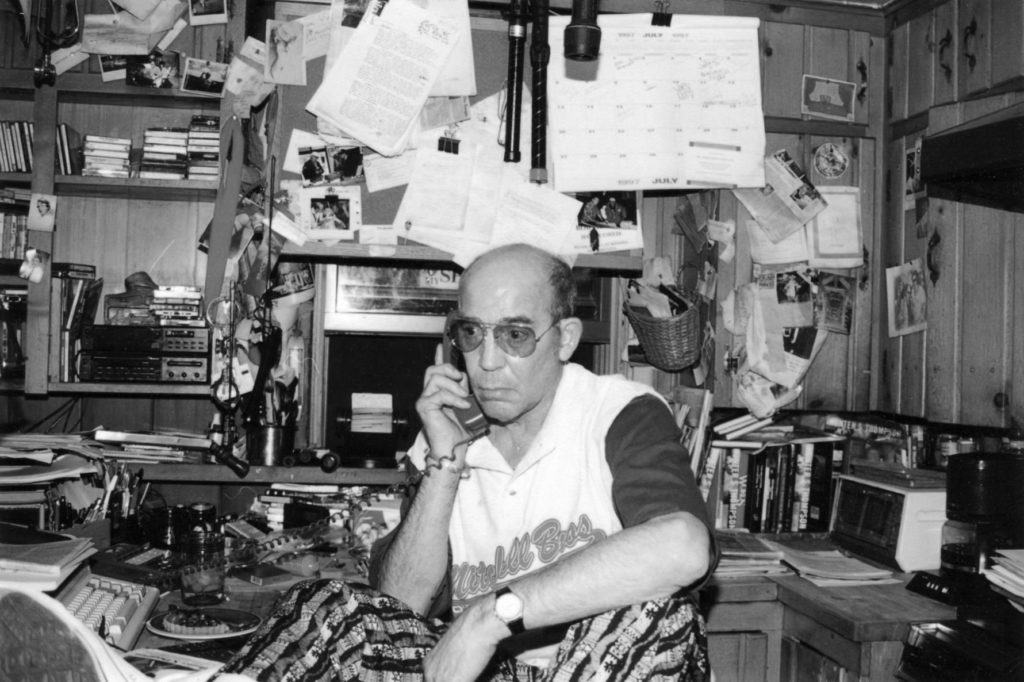

He gave up being a reporter and became instead a reactor. Back in Woody Creek, he discovered satellite dishes and cable news and spent the rest of his career reacting to the news he saw on television. His screeds found an audience of devoted fans and filled several books: Generation of Swine (Summit, 1988), Songs of the Doomed (Summit, 1991), Better than Sex (Random House, 1994) and Kingdom of Fear (Simon and Schuster, 2003). His continuing commercial success allowed him to publish his 1959 novel The Rum Diary (Simon and Schuster, 1998).

The pop-culture caricature of his personality – as a drug-gobbling and drunken madman – soon eclipsed his offstage personality as a serious writer. As a lazy hillbilly, however, he began to realize that he could make a living with self-parody and he did so. He watered and manured his image and allowed filmmakers turn him into the subject of a comic film, Where the Buffalo Roam (1981). Despite the film’s faults, it contained Bill Murray’s terrific performance as Thompson. Later, actor Johnny Depp, another Thompson acolyte, played him in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) and The Rum Diary (2012).

Thompson’s fortuitous meeting with historian Douglas Brinkley led to two collections of Thompson’s correspondence, both edited by Brinkley: The Proud Highway (Villard, 1997) and Fear and Loathing in America (Simon and Schuster, 2000). He wrote columns for ESPN’s website, collected as Hey Rube (Simon and Schuster, 2004).

Divorced since the early 1980s, Thompson had a series of romances, including a long relationship producer Laila Nabulsi, who managed to do the impossible, translating his supposedly unfilmable book, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, into a film (directed by Terry Gilliam.) Thompson met Anita Bejmuk when he became one of his editorial assistants. They wed in 2003.

Despondent over failing health and the nation’s political direction, Thompson committed suicide by gunshot on February 20, 2005. His high-profile funeral – during which his ashes were blasted from a cannon, accompanied by fireworks – was attended by the clerisy of Hollywood and Washington.

His observations about the nature of American politics remain undiminished in the years since his death, and his comments continue to resonate decades later, an astonishingly long shelf life for the work of a journalist. In recent years, his screeds devoted to Nixon have been dusted off and the eloquence of his powerful outrage feed a new generation.

NOTES

- “until the dark thumb of fate”: William McKeen, Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson (New York: Norton, 2008), p. 50.

- “my long-haired opponent”: Sophie Gilbert, “When Hunter S. Thompson Ran for Sheriff of Aspen,” The Atlantic, June 26, 2014.

FURTHER READING

- Brinkley, Douglas, Terry McDonnell, and George Plimpton. “The Art of Journalism I: An Interview with Hunter S. Thompson and His Journal Notes from Vietnam,” Paris Review, Fall 2000.

- Feehan, Rory. The Genesis of the Hunter Figure: A Study of the Dialectic between the Biographical and the Aesthetic in the Early Writings of Hunter S. Thompson (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Mary Immaculate College, 2018)

- McKeen, William. Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson (New York: Norton, 2008)

- Steadman, Ralph. The Joke’s Over: Gonzo, Hunter Thompson and Me (New York: Harcourt, 2007)

- Thompson, Hunter S. Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga (New York: Random House, 1967)

- _____. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream (New York: Random House, 1972)

- _____. Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72 (San Francisco: Straight Arrow, 1973)

- _____. The Proud Highway: The Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman (New York: Villard, 1997)

- _____ Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000)

- Thompson, Toby. The 60s Report (New York: Rawson, Wade, 1979)

- Vetter, Craig. “The Playboy Interview: Hunter S. Thompson, Playboy, November 1974

- Wenner, Jann, and Corey Seymour. Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson (Boston: Little Brown, 2007)