Hunter, Behind the Shades

Appeared in Creative Loafing, August 13, 2008

Interviewed by Wade Tantangelo

Hunter S. Thompson biographer William McKeen recently returned to Florida from the first leg of a book tour that included his most feared stop: Aspen, Colorado. For decades, the late Gonzo god wrote, detonated explosives and maintained an around-the-clock buzz at his Owl Farm, a “fortified compound” outside the ski resort town.

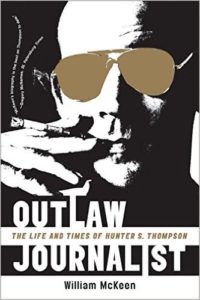

McKeen, author of the excellent new hardcover Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson, figured he might be dragged into the mountains and mauled if the good doctor’s old pals and conspirators felt the book wronged their flawed hero, who blew his brains out in 2005.

“If I survived Aspen I think I’m OK,” McKeen says from his office at the University of Florida in Gainesville, where he’s a professor of journalism. “That was the toughest audience. All his close friends were there.”

Those friends included Pitkin County Sheriff Bob Braudis, who was one of Thompson’s most trusted allies. (He’s quoted extensively in Outlaw Journalist.) “[Braudis] put his arm around me and said, ‘Great fucking book, kid,’ McKeen says.

“I want critics to like the book but it’s more important to me to get positive feedback from people like that. Even [Hunter’s widow] Anita Thompson — who is very difficult to please, she’s very protective of his legacy — gave me a great shout-out on her blog.”

McKeen’s cradle-to-grave bio of the journalistic badass doesn’t sidestep the “fear and loathing” that Thompson inspired even in friends and family. Nor does it overlook the alcoholism and cocaine addiction that many Thompson watchers — including Rolling Stone chief Jann Wenner — feel robbed the genius of his talents by the mid-1970s.

“I knew that he was not a perfect human being,” McKeen says. “But I hated learning about his abuse of women and friends. You could be his best friend in the world, but in his reckless desire of women, he’d take your wife home. It didn’t matter that you were his best friend. That’s disturbing to me. But I really admired his commitment to the struggle of being a writer in the early years when he received no positive feedback.”

Thompson’s classic 1970 Rolling Stone article “The Battle of Aspen” seduced a young McKeen. The piece chronicles the city’s 1969 mayoral election and the rise of the region’s Freak Power movement, which Thompson mobilized the following year in a bid for sheriff that he nearly won.

The biographer first met Thompson years later, after 1966’s Hell’s Angels had made him a darling of the literary world and 1971’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas catapulted the Gonzo journalist into a realm of celebrity typically reserved for screen and sports stars. The encounter took place when McKeen was teaching at Western Kentucky University in the late 1970s. The professor interviewed Thompson on stage at a speaking engagement.

“I suppose, like others, I expected a mad-dog character,” McKeen says. “In fact, he was a polite, quiet, soft-spoken, almost shy guy.

“Walking up to the stage, his body changed. He became this loping figure, jerking his head around, trying to play up to the role. Like all Hunter speaking engagements, it was a disaster. But he had to do them. He made more money from those than writing. I discovered how he lived from paycheck to paycheck. Even when he was at the top of his game, he lived hand to mouth.”

McKeen’s bio smartly focuses on Thompson’s singular writing style, his mastery of invective and the lengths he went to make sense of a world gone wrong. McKeen adroitly dismantles the Raoul Duke persona exploited by uppity doodler Garry Trudeau, as well as Hollywood and Thompson himself. The book addresses the Gonzo journalist’s acts of brutality and self-destruction but keeps the emphasis on the writer and his ability to demonstrate the “power of language when used well.”

Unlike other Thompson tomes, Outlaw Journalist has the blessing of historian Douglas Brinkley, literary executor of the Hunter S. Thompson estate and editor of The Proud Highway and Fear and Loathing in America. Brinkley’s input led to some of the book’s most fascinating revelations, like the existence of a politically charged Fear and Loathing at the Gun Club manuscript, written pre-Vegas. “I think it will see the light of day,” says McKeen.

The biographer is clearly a Thompson fan, but he’s a scholar and critic first. In Outlaw Journalist, there’s an irreverent playfulness to his prose that echoes Thompson’s style without aping it. And at the end of the 428-page bio, even skeptics will likely agree that the Gonzo god belongs in the pantheon of top American writers.

“In my first Thompson book [Hunter S. Thompson, published in 1991] I put in a comparison to Mark Twain and an academic editor took it out. Editors win,” McKeen says. “In his obit for the Wall Street Journal, Tom Wolfe called him the 20th century’s Mark Twain. I was there first.”