His Back Pages

From The Satellite Magazine, November 2004

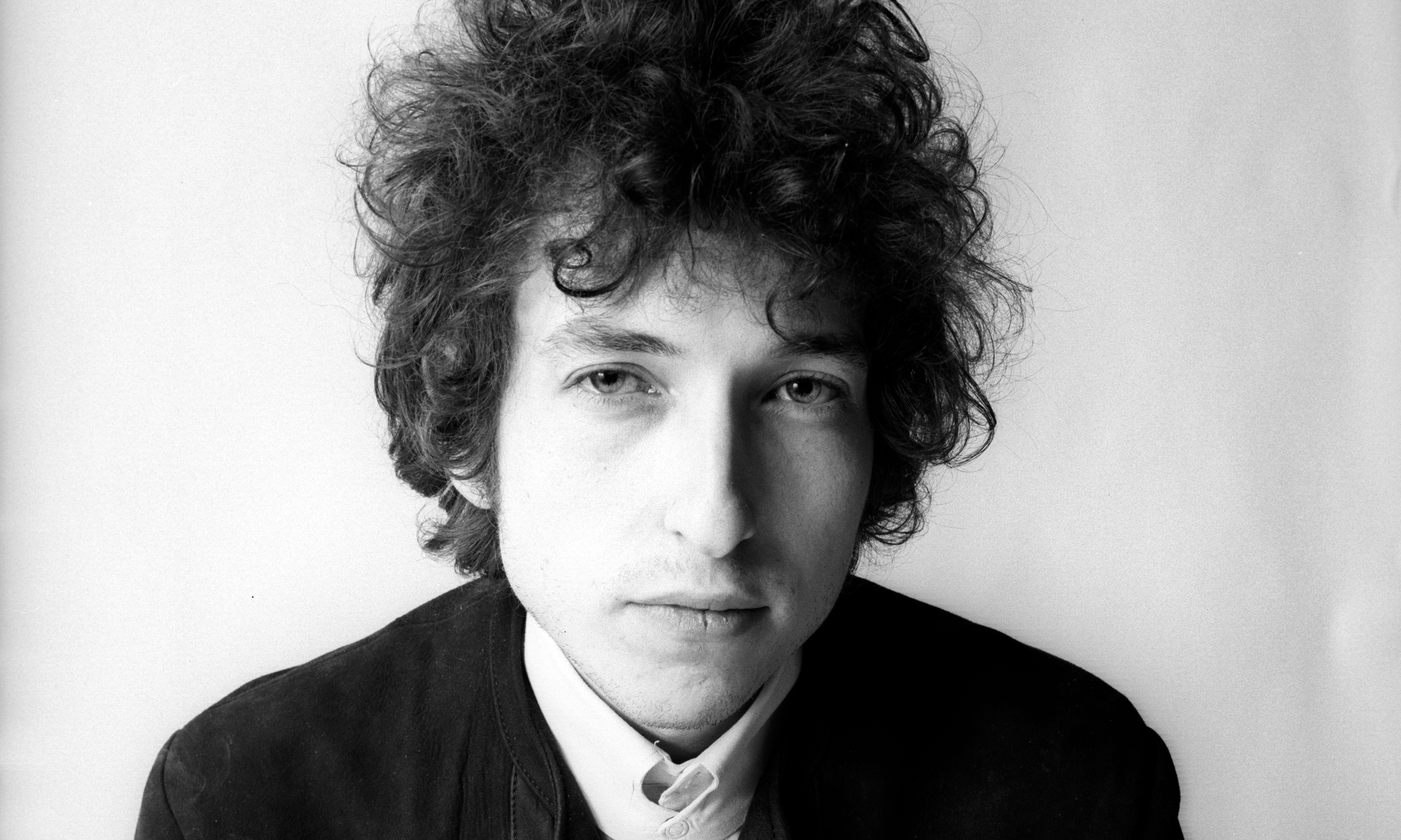

We’re all haunted by the past, but few of us have a past like Bob Dylan’s. At 63, His Grand Exalted Mystic Bobness is not going gentle into that good night. From a concert stage somewhere on the planet tonight, he will rage against the dying of the light. Yet his ghost – the younger man with the exploding hairstyle, jackboots and magnificent whining voice – is all around us: on film, in books and, of course, on our stereos. In his autobiography (Chronicles, Vol. 1, out in paperback this month), Dylan regards his earlier, younger self as “that other guy,” as if he was some long-lost acquaintance. Fitzgerald said there were no second acts in American lives. Yet Dylan, in his third act, seems comfortable in his skin and not afraid that he left all of his best performances in that stunning first act.

He couldn’t allow us all to revel in his past so much if he wasn’t so content in the present. His last two albums, Time Out of Mind and Love and Theft are among his best work: rich, full of humor, apocalyptic imagery, brilliant musicianship and that ragged and dirty rasp that one writer described as sounding as if it came out of a broken speaker. Old Bob, this third-act Bob, is still a brilliant creative artist. He’s also confident, and so he doesn’t mind sharing stage time with “that other guy.”

Hence the weenie-roast of Bob Dylan books and CD’s in the wake of Martin Scorsese’s massive documentary, No Direction Home, that aired on PBS’ “American Masters” series in September and has been released in an extended version on DVD.

Hence the weenie-roast of Bob Dylan books and CD’s in the wake of Martin Scorsese’s massive documentary, No Direction Home, that aired on PBS’ “American Masters” series in September and has been released in an extended version on DVD.

The Scorsese film is the centerpiece of the Banquet of Bob, and it’s worth all the fuss. Dealing mostly with five years (1961-66) of Dylan’s life, it’s as focused as it can be, considering the subject is a moving target. Reflective, thoughtful and often funny, the interview segments with AARP Dylan looking back allow him to continue the process of self de-mystifying that began with Chronicles. But Dylan’s off-the-cuff, spoken comments are those of a man with an uncanny ability to draw poetry from common speech. Talking about a couple of his high-school girlfriends, he looks straight into the camera and nearly winks. “Those girls brought out the poet in me,” he says.

Those die-hard Dylan fans who still haven’t forgiven Dylan for “going electric” in 1965, eschewing work-shirt political songs for polka-dotted rock’n’roll, will be interested in Dylan’s reflections on that era. “You can be supportive of a cause and still not be political,” he says, after Pete Seeger and several other dedicated activist/artists tell of their disappointment in him. Indeed, Scorsese uses Dylan’s step into the rock arena as the central theme in this nearly four-hour film about artistic growth. Abruptly flash-forwarding from baby-faced Bob the “protest singer” to rock star Bob on tour with the Hawks in 1966, Scorsese builds dramatic tension in the confines of what is basically a straight-forward chronological tale.

Dylan’s old friends from high school, his Greenwich Village pals and former lovers also show up. Joan Baez, still radiant and philosophical, sips coffee in her kitchen and laughs her way through the heartbreak that was her one-sided love affair with Dylan. He also addresses that period with wistfulness: “It’s hard to be wise and in love at the same time.”

The performance footage, much of it more than 40 years old, is startling. Dylan plays “Mr. Tambourine Man” for the first time in public at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival as Seeger sits next to him, visibly impressed by what he hears. No scratches, no scars, no sprocket holes – the film has the clarity of an Ansel Adams photograph that moves. (The DVD contains full-length versions of performances excerpted in the film.)

The images from the 1966 World Tour with the Hawks (who later became famous as the Band) are steeped in the chaos of that confrontational tour, as European fans turn up at the shows to respectfully cheer Dylan solo and to boo him when he takes the stage for the second half with the rock band. Even in this bleary, amphetamine-fueled madness, Dylan still shows his humor, telling the stage manager as he leaves that he wants the names of every member of the audience who booed.

The film as shown on PBS stands, but the DVD extras make No Direction Home especially valuable for Dylan fans. In addition to the full-length performances, there are performances of Dylan songs by some of his friends, filmed during the interviews: Liam Clancy sits at a bar with a beer the size of a space shuttle and whispers “Girl from the North Country.” Baez, still in the kitchen, plays that song Dylan never finished, “Love is Just a Four-Letter Word” and simultaneously breaks your heart and makes you laugh (with her long-voweled Dylan impersonation). And Maria Muldaur closes her eyes and gospelizes Dylan’s little-known “Lord, Protect My Child” – a truly glorious performance.

The companion double-CD set, No Direction Home: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 7, has several of the performances in the film but adds to it with recordings that even serious Dylan bootleg collectors might not have heard, such as a ramped-up “Visions of Johanna.” One disc focuses on acoustic Dylan and the other on mostly studio outtakes form the electric period. Those interested in the creative process will be fascinated by the outtakes. This is what it sounded like 10 minutes before genius and inspiration arrived.

Long so protective of his life and privacy, Dylan’s Chronicles came as a revelation and surprise, but he did not deal with the same part of his life Scorsese does in the film. Chronicles is in four distinct sections – before fame, after fame and suffering writer’s block, suffering writer’s block again 20 years later and finally flashing back to his life before fame. With this remarkable structure, Dylan leaves out the focus of Scorsese’s film – the artist-in-transition period of 1961-1966. Dylan’s life is rich enough to support all of these autobiographical treatments.

Long so protective of his life and privacy, Dylan’s Chronicles came as a revelation and surprise, but he did not deal with the same part of his life Scorsese does in the film. Chronicles is in four distinct sections – before fame, after fame and suffering writer’s block, suffering writer’s block again 20 years later and finally flashing back to his life before fame. With this remarkable structure, Dylan leaves out the focus of Scorsese’s film – the artist-in-transition period of 1961-1966. Dylan’s life is rich enough to support all of these autobiographical treatments.

And it’s rich enough to support an odd collection called The Bob Dylan Scrapbook, focused on Dylan’s life until 1966 and featuring, among other things, a reproduction of a page from Hibbing High School’s yearbook with his ambition to “join Little Richard” listed under Robert Zimmerman’s goofy senior picture. Dylan has also allowed Starbuck’s to release his long-bootlegged coffee-house recordings as Live at the Gaslight, 1962 and those who order from Dylan’s Web site get yet another new / old disc, Live at Carnegie Hall 1963. Both collections are excellent.

And he gets the semi-serious academic treatment as well. In the aftermath of last year’s Dylan’s Visions of Sin by scholar Christopher Ricks, Greil Marcus – perhaps the finest writer to study rock’n’roll and its place in American culture — focuses an entire book on Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” which was anointed by Rolling Stone (but of course) as rock’n’roll’s greatest song. As with his other fine books (Mystery Train and Invisible Republic among them), Marcus’s Like a Rolling Stone anticipates that in a hundred years, scholars will still be combing through Dylan’s words looking for meaning. In No Direction Home, Joan Baez laughs over her coffee cup, and says that when they were together 40 years ago, Dylan would show her his writing then ask what she thought it meant. When she confessed she didn’t know, Dylan would say he didn’t know either. But then he would laugh, thinking about all of the meanings that scholars would hang on his words and he loved confounding people. Way back then, in 1963, Dylan had a pretty good sense of who he was and what he would become.

So he has no problem reveling in this ancient history, because he has nothing to fear from his past.