Truth is Never Told in Daylight

From Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson (W.W. Norton, 2008)

This chapter shows us post-Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas Hunter S. Thompson, a writer on top of the journalistic pyramid. Jann Wenner, editor of Rolling Stone, was so pleased with his star reporter’s work that he gave him a blank check to write about whatever he wanted. Thompson chose to cover the 1972 presidential campaign from beginning to its foul end.

. . . . . . . . .

Hunter was still the new guy on the Rolling Stone staff. He’d done the self-indulgent piece on his sheriff’s campaign, then followed with the huge account of Ruben Salazar’s murder and its aftermath. But it was “Fear and `Loathing in Las Vegas” that gave Hunter carte blanche with Jann Wenner. Some of those in Wenner’s loft resented the strange new guy who so quickly became the editor’s favorite. Whatever Hunter wanted, Hunter got. Wenner recognized the power of Hunter’s voice and wanted more madness, more over-the-top craziness.

“We loved what Hunter did,” Charles Perry said, shrugging off the office carping as mere whining.

So Wenner opened the door. What do you want, Hunter?

What Hunter wanted was one of the things Wenner had tried to avoid: politics.

As soon as Hunter got the go-ahead from Wenner, he packed up a trailer, hitched it to his Volvo 174 and set off for Washington, to set up the National Affairs Desk, in the middle of a blizzard. “Driving across goddamn Nebraska with a huge Doberman, pulling a giant U-Haul trailer, driving through a storm,” Hunter remembered, “These big 18-wheelers looming up on me suddenly out of the white. I couldn’t go fast enough, couldn’t see, blind in the snow . . . .”

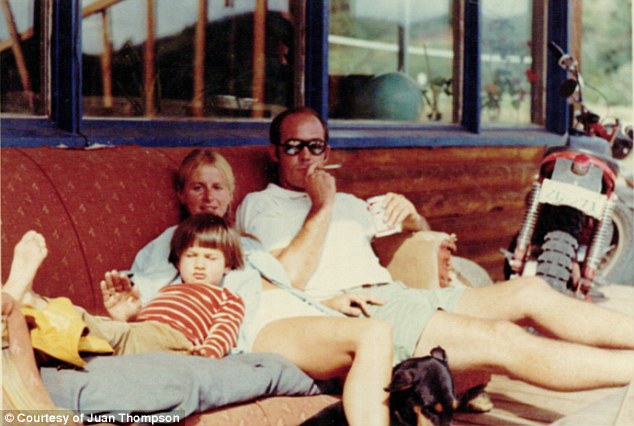

He also had serious doubts about what he was doing. Why politics? He was a neophyte who had been radicalized by Chicago 1968, but did he really want to give over a year of his life to this? Wenner had given him a telefax machine, the ancestor of the fax machine that Hunter had dubbed the Mojo Wire. Sandy and Juan had come along and at Rolling Stone expense they rented a two-story brick home in the Rock Creek section of the city, an established family neighborhood. It was on the less-fashionable side of Rock Creek Park and most of the movers and shakers were living in Georgetown, but to Sandy it was a step up. She felt that they were finally in the big leagues.

“I was pregnant again,” she said. “This was going to be my last shot. I asked the doctor what my odds were. He said, about twenty-five percent. I said, OK. I’m willing to do it. I wanted a child mostly because I wanted another Hunter. I wanted more of that energy on this planet.

The Thompsons rented out Owl Farm and took over the furnished home, maintaining its conventional appearance but for the dining room, which became Hunter’s de facto office when he was in town. As the campaign fever began to intensify that fall, the Rock Creek house became more office than home, as journalists dropped by to talk to the new sensation.

“He was dealing with The Heavies,” Sandy said. “He was playing with The Players. And he was even winning. But it was taking its toll.”

Almost as soon as Hunter settled his family into the Washington house, he flew cross country for a major Rolling Stone editorial conference. The editors were purely a boy’s club at the end of 1971. They met for the magazine’s first off-site editorial conference at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur in December. For Wenner, it was a power statement, as he had the bureau chiefs from Los Angeles, New York, and London fly in to romp nude in the hot tubs, get high and contemplate the future of his five-year-old publishing venture. No business types or women (other than Annie Leibovitz, the staff photographer there to document the event) were allowed.

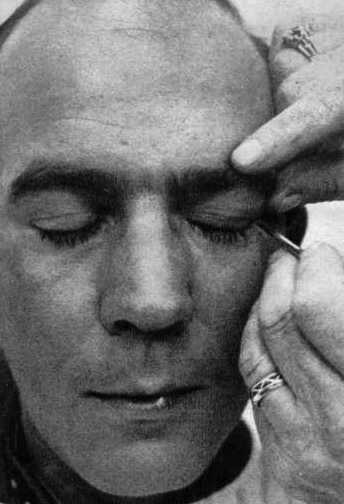

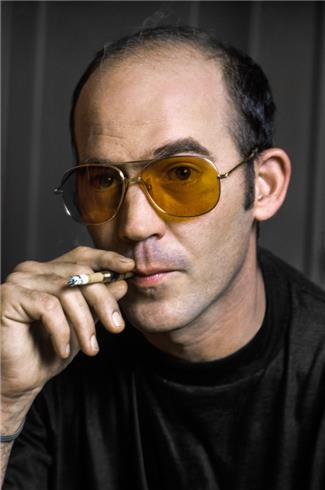

The whole Hee-Haw gang was there: Wenner, Thompson, Joe Eszterhas, Grover Lewis, Charlie Perry, David Felton, Ben Fong-Torres, Jon Landau … all of the major players on the staff, knee deep in testosterone. They were mostly there for partying, and at the editorial meetings, Wenner pontificated and lulled his charges to sleep. Editor Paul Scanlan said Wenner’s diatribes were “the most excruciating eight or nine hours I ever went through.” Hunter wore a hospital smock and a robe and drew heavily on his cigarette, inscrutable behind sunglasses. Sometimes, to liven up things, he pulled on one of his trusty blonde wigs. He also entertained the staff by screaming, yelling, and throwing furniture when he wanted Wenner’s attention. “Everyone egged Hunter on,” editor Robert Greenfield said. Alan Rinzler, who ran Straight Arrow, said, “There was almost a macho thing of who could keep up with Hunter, be the craziest, do the most drugs.”

The major worthwhile development at the conference was the tacit agreement that Hunter would cover the 1972 presidential campaign. He would do the whole thing, from the frozen-tundra New Hampshire primary though the sweltering political conventions, through the fall full-bore campaign, until the last ballot was counted on election day. “There was a lot of talent in that room,” Hunter said years later, “but when it came to politics, I was the only one that raised my hand.” Wenner did not have any trouble selling the idea to the rest of his staff, since earlier that year the 26th Amendment to the Constitution granted 18-year-olds the right to vote. The newly enfranchised voters formed the core of Rolling Stone readership. And although Wenner had avoided plying his magazine with radical politics and rhetoric and instead built circulation with serious and detailed music reporting, but he figured it might be time to test the magazine’s power with its audience. Educating the masses, and perhaps delivering the coveted Youth Vote to his favored candidate, was the sugar plum dancing in Citizen Wenner’s head.

Hunter was stoked about the campaign and if there was dissent among the staff, no one spoke at Big Sur. “When we decided to cover the 1972 political campaigns,” Perry said, “there was really no debate about it. Everyone was behind it. Hunter was never resented, because we all admired him so much. His writing was so good.” The magazine was already veering away from its bread-and-butter of music reporting, with long, cultural reporting by Joe Eszterhas and elegant profiles of mainstream celebrities (Robert Mitchum, Lee Marvin, Paul Newman) by Grover Lewis, all of which helped broaden the reader base.

But politics would really test the Rolling Stone audience. It was a fine line. Though the mainstream media lumped the magazine in with the underground press (The Berkeley Barb, The L.A. Free Press), Wenner had avoided that radical out-of-the-mainstream taint as the kiss of death. He hoped to make Rolling Stone into a tie-dyed Time magazine.

He also realized that he’d stumbled into finding a unique voice in modern journalism. Despite Hell’s Angels, Hunter wasn’t yet widely known in 1971. “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” had drawn raves when it appeared in the magazine and Wenner wanted to strike, to tie down Hunter with a contract. Hunter, who hadn’t drawn a regular paycheck since his days as a Time copy boy, came cheap: he got a $1,000-a-month retainer from Rolling Stone and a deal for a book on the campaign when it was all over. What he didn’t realize is that Wenner would take Hunter’s considerable expenses out of the money promised for the paperback sale of the book.

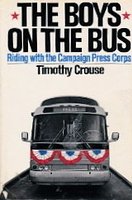

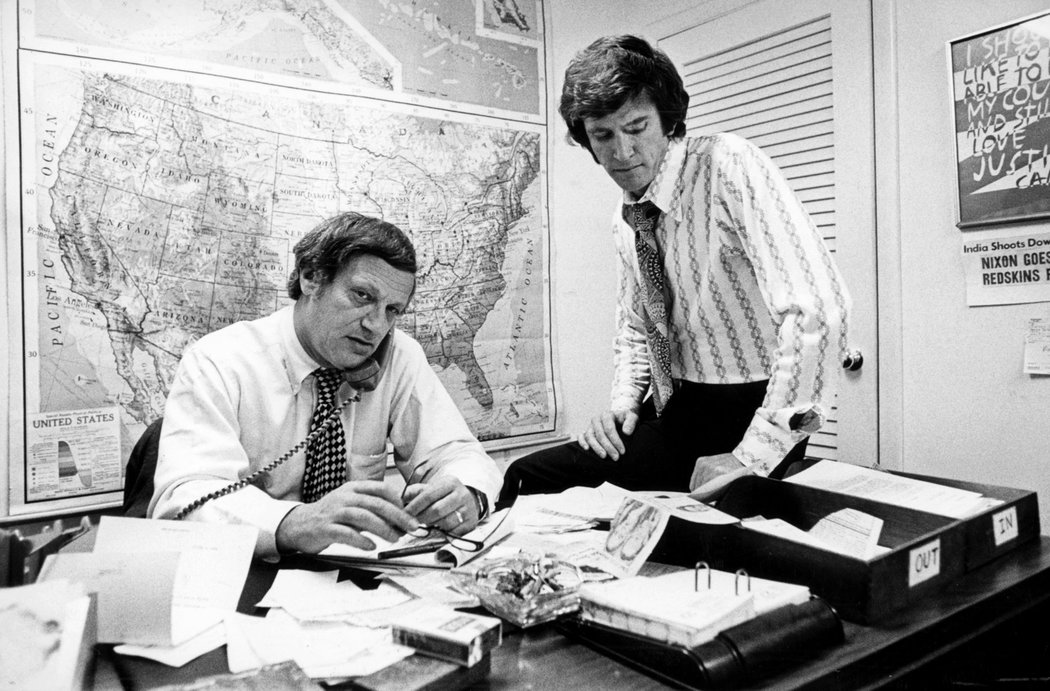

Wenner knew that Hunter, with his odd worldview and even odder work habits, might not be a reliable political correspondent, so he assigned Timothy Crouse to babysit him. The son of playwright Russel Crouse (winner of the 1946 Pulitzer for drama for State of the Union), Crouse was a Harvard grad with a couple of years on newspapers and a monumental stutter. The often-abrasive Wenner enjoyed exploiting weakness, which only amplified Crouse’s stutter. Because Crouse wanted to be a contributing writer on the staff, he was eager to help Hunter Thompson, hoping he might learn something. “I didn’t know what I was getting into,” Crouse said. He started the campaign as Hunter’s babysitter, and he ended up benefiting professionally from Hunter’s generosity and friendship.

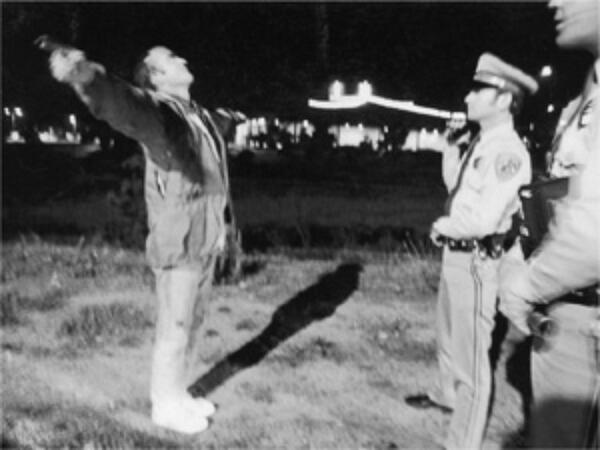

The highlight of the Big Sur conference came after hours. Hunter, Felton, and Leibovitz were speeding up Highway 1 when a state trooper pulled them over. Hunter was driving and he had a head full of mescaline. The officer decided to test Hunter’s sobriety and asked him to touch his nose with his finger. Hunter missed. He was on the brink of arrest when he suggested another test, a feat of daring. The officer agreed and watched, flabbergasted, as Hunter flipped his sunglasses off the back of his head and caught them behind his back. The officer let him go.

But the Esalen Institute had had enough of Hunter’s antics. After three days of drinking, screaming, and furniture throwing, the editors of Rolling Stone were ordered to leave.

Back in Washington, gearing up for the quadrennial masturbatory madness of a presidential campaign, Hunter took stock of his life and work. Still flushed with the success of “Fear and Loathing” in the magazine and awaiting the end of the legal wrangling that would hold up book publication for another six months, he found himself well outside his comfort zone. The hip young journalists knew who he was and some of them came by Rock Creek to kiss his ring, but as he imagined the next year and all of the simple logistical crises he would face, he realized how important Sandy had become to him – not only as his wife and partner, but as the one-woman support system who made it possible for him to be the raving beast Hunter S. Thompson.

“I’ve grown accustomed to letting her deal with my day-to-day reality and keeping the fucking weasels off my back,” he told Wenner. “I need a human buffer to keep well-meaning people from driving me fucking nuts.”

Sandy was the one who answered the phone and explained Hunter. He’s still sleeping . . . he’s soaking in the tub . . . he’s too upset to speak. She kept the world at bay. But Sandy would not be on the road with him; she was pregnant and she had a precocious seven-year-old at home. Out on the road, Hunter would have to exist without her.

And he would be an indentured servant to Wenner and Rolling Stone. Hunter was not a man who suffered authority gladly, and his relationship with Wenner, though fond, was also testy. The political stories appeared in the magazine under the “Fear and Loathing” headline. Hunter had given Rolling Stone an extremely valuable franchise, and he wanted Wenner to keep that in mind.

The frustration and the rupture in living arrangements and duties took a toll on Sandy. “I had taken up smoking – and drinking a lot,” she said. “Here I am pregnant, right? The doctor gave me a prescription for Valium. Hunter was just so much in his own thing, in his own world, that he wasn’t aware until I got really outrageous. He didn’t know that every single night I was drunk.”

Both the pressure of writing bi-weekly campaign reports and the political passions of the time kept Hunter on edge. Being on the road also led him astray. He’d never been entirely faithful. His visits to San Francisco were often marked by new liaisons with women on the Rolling Stone staff. Sleeping with Hunter raised them in Wenner’s eyes, made them more valuable employees. On the road, there were scores of young campaign workers and political groupies, and Hunter did not resist.

The politics and his up-close look at the people who were running his country into the ground were enough to drive Hunter insane. Add the deadlines, and Hunter was an impossible brute. “There was a lot of madness,” Sandy recalled. “Hunter had begun to get angrier. And more violent. His language was more violent. He was louder. He was tenser.”

The 1972 presidential campaign cranked into gear with Democratic hopefuls duking it out for the right to face Richard Nixon in the general election. In the early days of the New Hampshire primary, small clusters of reporters followed the candidates around.

To much of America and certainly those within the bubble of politics, Rolling Stone was still a mystery. Some political aides looked at the credentials dangling from Hunter’s neck thought Hunter was a member of the rock band (Noisy bastards, aren’t they?) or that Rolling Stone was a fan magazine for the group.

The other gentlemen of the establishment press weren’t any warmer to him. They saw him as the odd-looking, ill-attired writer from that Rolling Stone thing who was constantly late, delaying the press bus’s departure. He was noisy, often on something, and carrying a six pack.

Political reporting went through a major change in Hunter’s generation. When Hunter was growing up, it was difficult to maintain interest in politics. After 12 years – a lifetime – of Roosevelt, the nation was presided over first by a haberdasher, then a grandfatherly war hero, who faced the same bald Democrat in the elections every four years. The presidential election of 1960 was a watershed and offered a clear choice. John F. Kennedy drew political teeny-boppers into the mix. Clearly, a lot of the young people at JFK’s campaign rallies could not vote, but they turned out to cheer the candidate as if he were the new Elvis.

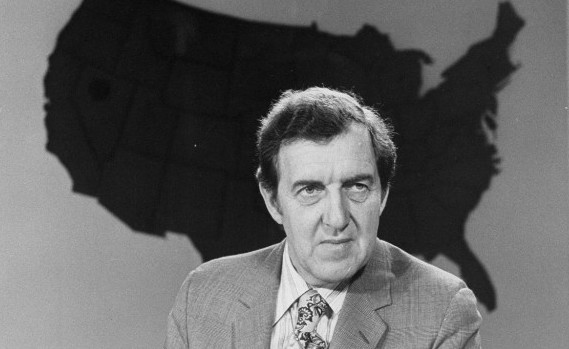

The Kennedy-Nixon election also was a turning point for press coverage of presidential campaigns. Television had stumbled into live coverage of the political conventions in 1952 and slowly gone from being a novelty to a major part of the political process. After the first night of live coverage of the 1952 Democratic convention in Chicago, CBS News producer Don Hewitt was finishing breakfast at a greasy spoon across from the convention hall, trying to figure out how to cure one of his big headaches. While showing someone on the convention floor on camera – Senator Stuart Symington, let’s say – how did he tell viewers that they were looking at Symington without interrupting the jabbering host, correspondent Walter Cronkite? At that moment, the gum-snapping waitress came up and asked Hewitt if there was anything else he wanted. Hewitt looked beyond her, to the sign announcing “Today’s Specials.” Sure, Hewitt said, I want to buy that sign. He’d figured out that if they could use the letters to put names of delegates on the sign, they could photograph it, drop out the black background and super-impose the name on the picture of the talking head, all without interrupting Cronkite. The lunch-counter invention revo- lutionized TV coverage for live events.

The 1960 campaign was made for television, with the tousle-hair Kennedy versus the stubbly Nixon, and the televised debates that fall were deciding factors for many voters, who responded to the image of the candidates as much as the content of their political platforms.

It was also the year that campaign coverage was re-invented by Theodore H. White. For generations, political reporting and commentary had been the province of chin-stroking columnists and snoremongers. The major decisions, according to lore, were made by stogie-puffing pols in smoky back rooms. White was a long-time reporter for Time and LIFE magazines, who wanted to explain the political process to the masses. He followed the candidates through primary season, then worked the hotel rooms and hallways during the party conventions, and followed Nixon and Kennedy up through election day. When it appeared in 1961, The Making of the President 1960 was an immediate best-seller, found on all the best coffee tables in America. No journalist had thought to bring average readers into the tent before and White’s innovation changed the way the press reported politics.

In 1960, White had a lot of face time with the candidates. By 1964, more reporters followed candidates through primary season. By 1968, when White was working on his third Making of the President book, the crowd was stifling. But White’s 1968 volume was surpassed by a book focused on political marketing by 26-year-old newspaper reporter Joe McGinniss. The Selling of the President was a book Hunter could easily have written, since his Pageant article on Nixon was about rehabilitating the image of a damaged-goods candidate.

By 1972, covering a political campaign had become near-routine; reporters were said to be Doing a Teddy White. With Hunter and Tim Crouse along for the ride that year, campaign coverage went through more changes and both Rolling Stone writers were to publish books with long shelf lives.

With a sitting president, the Republican nomination was a surety: Richard Nixon, who in 1968 staged the most remarkable political comeback in American history, was in.

The 1972 Democratic race was a free-for-all. First came the shadow candidate, Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts. As the next Kennedy in line for succession, he was wounded by a scandal – his actions following the drowning death of a young woman in his company in 1969. The Chappaquiddick incident, with its implicit infidelity and irresponsibility, damaged Kennedy politically, but he still had something the other candidates did not: the royal bloodline.

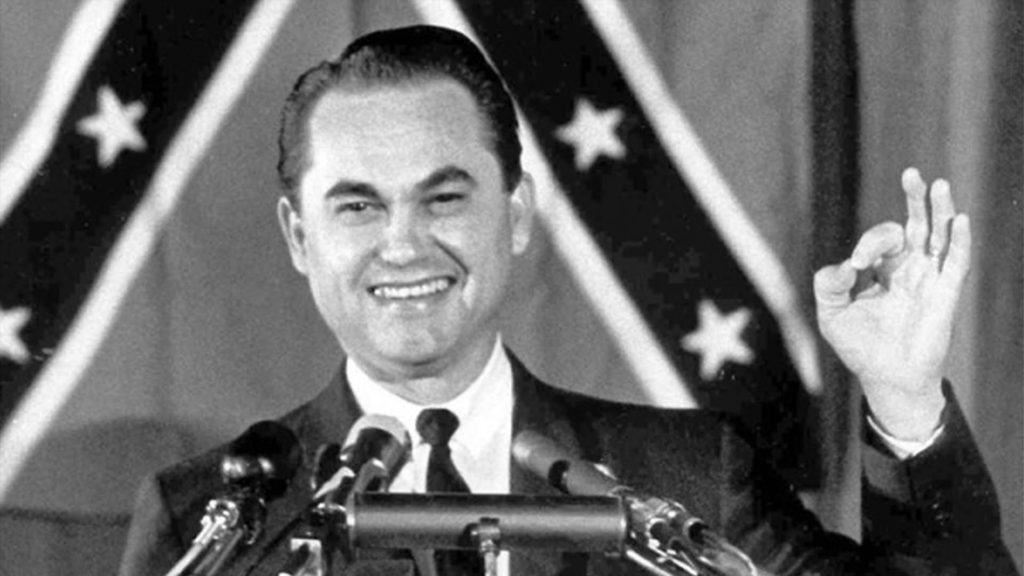

Edmund Muskie, the failed vice-presidential candidate from four years before, was the early favorite. There was also former vice-president Hubert Humphrey, the senator from Minnesota. Washington Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson was also in the mix. Alabama governor George Wallace, who had run on a third-party ticket in 1968, was back to preach his segregationist philosophy to the nation. There were others: Eugene McCarthy, 1968’s Quixotic peace candidate, making another try; Shirley Chisholm, the black congresswoman from the Caribbean, by way of Queens; John Lindsay, the smoothie mayor of New York; and Wilbur Mills, the Arkansas good old boy who ran the House Ways and Means Committee.

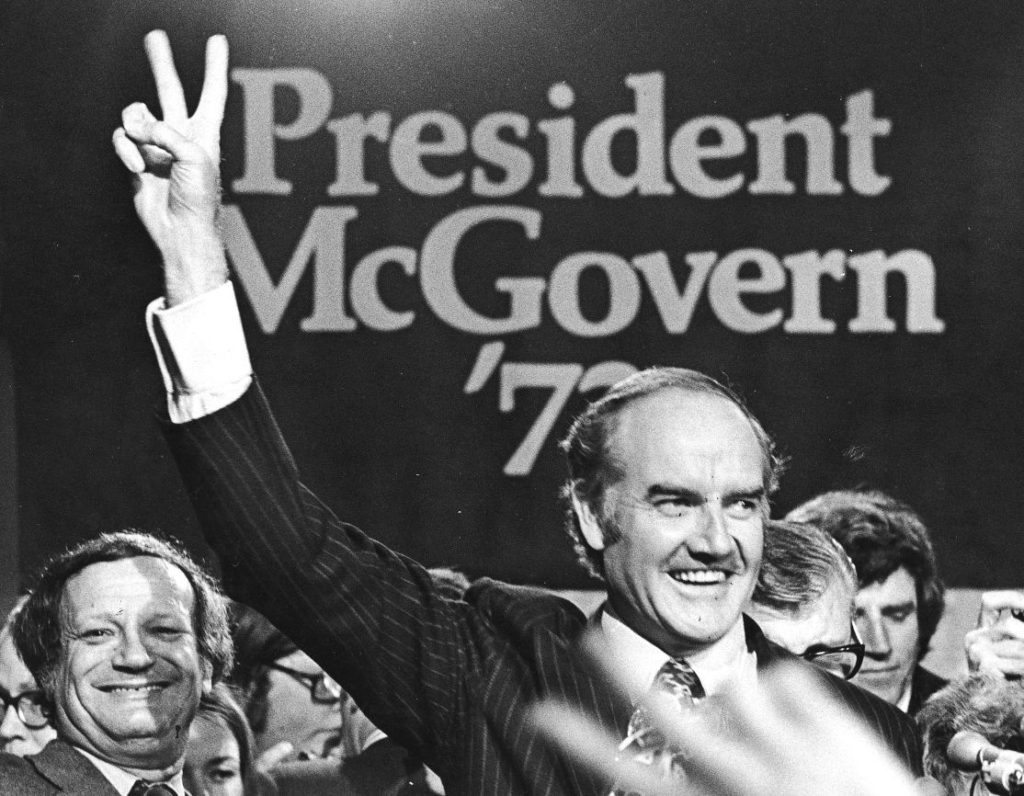

In that huge field, the genial and mild-mannered George McGovern did not stand a chance. In 1968, McGovern had picked up the fallen standard when Senator Robert Kennedy, the “peace candidate” had been assassinated. In 1972, McGovern’s campaign manager, Gary Hart, knew it would be an uphill battle because the candidate was from a small state and had the stage presence of an 11th grade social-studies teacher. “It was a complex and complicated time,” Hart said. “It was a long-shot presidential campaign in the middle of social revolution involving the Vietnam War, civil rights, gender rights, environmental movement – a lot of the social and cultural revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s.”

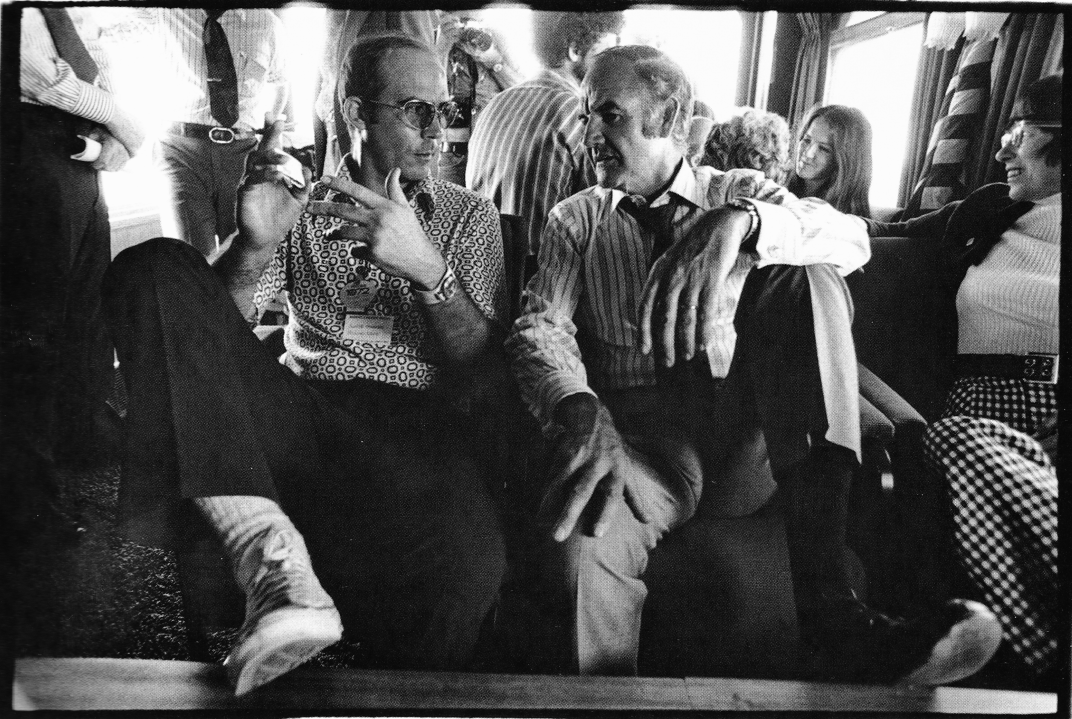

It was clear from the start, once Hunter’s “Fear and Loathing” political dispatches began appearing in Rolling Stone, that McGovern was the only candidate Hunter cared about. He admired both the man and his principled politics. Despite the wisdom that put the betting money on Muskie or Humphrey, in the early days of the New Hampshire primary campaign, Hunter followed around McGovern, the only man he felt had the integrity to do what he promised if elected: extricate the nation from the hell of the Vietnam War. Hunter would rather blow a dead dog than listen to a speech by Muskie or Humphrey. There were times, during the dark-winter-hand-shaking days at factory gates with McGovern when there were only four reporters covering the candidate, and two of them were from Rolling Stone.

Hunter could not fathom how the political reporters for the major papers could face a deadline every day, when having a story due every other week was killing him. Crouse, with his newspaper experience, turned out to be a useful and experienced hand-holder. Hunter worked hard, but on his own terms. Deadlines were chaotic, both for Hunter on the road and for the Rolling Stone editors in San Francisco. When the pages started spewing out of the telefax machine in San Francisco, they were rarely in coherent order. The first page might have “Insert K” scrawled at the top . . . and then the next page might have no relation to that first page. Spreading the papers over the floor of the Raoul Duke Room and then putting them together in some coherent order usually fell to David Felton or Charlie Perry. As copy chief, Perry had the final duty of packaging Hunter Thompson for readers. “A lot of Hunter’s stuff would come in in the form of inserts,” Perry said. “There would be no lead, no walk-off, just the inserts and we’d sort of have to shuffle them around until we came up with a mosaic we liked.”

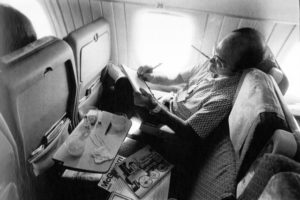

As the campaign grew, Hunter found himself on the press bus with the big-time reporters from the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe and other papers. They resented him from the start: Slogging to the bus, pre-dawn, to witness the candidate-of-the-day shaking hands at factory shift-change, waiting in the parking lot. Cold, impatient, inhaling bus fumes, anxious about deadline, wondering what-in-the-hell is the holdup. Finally, that noisy thug in the flop hat and the athletic shoes comes down the aisle, bumping the other reports with his baggage and his trailing six pack. In the back seat, still noisy and unrepentant. You mean, we were waiting for that?

That was Hunter Thompson, but few of the straight reporters knew who he was. Soon, though, some of the editors of the major dailies were reading Hunter’s dispatches and heckling their reporters on the road: How come you can’t write stuff like that? The reporters read what Hunter wrote about the candidates – things they thought, but could never write . . . not in a family newspaper . . . and developed a grudging respect for the noisy creature in the back of the bus.

So far, Muskie was the media-anointed favorite when the year began and he fulfilled his promise by winning the majority of delegates at the Iowa caucus in January and winning the New Hampshire primary in early March. The Florida Primary in the second week in March was to be a bigger test. Muskie hoped to continue the steamroller leading to his nomination in Miami. He planned a whistle-stop tour in a train called the Sunshine Special.

Monty Chitty was a 19-year-old student at the University of Florida who worked as a photographer on the school paper, the Alligator. Early in the winter, he’d applied to be one of two state college students to ride the Sunshine Special as accredited members of the press. Anything to get out of classes, Chitty figured, and so he made a deal (“either I traded pot to a faculty member, promised to give up my job as one of the editors, or wrote some idiotic essay”) to get one of the seats. He hitchhiked to Jacksonville the morning of the campaign run, obtained his credentials and boarded the train.

There were a lot of suits and a lot of media heavies on board (“There’s Frank Reynolds of ABC!”), all very friendly, quick to chat with the two college journalists, especially the “knock-out brunette” (Chitty’s term) representing another school. By noon, after four hours on the campaign train, Chitty was already jaded. He’d witnessed the “true underbelly” of network TV: unloaded cameras, orchestrated events in front of hand-picked crowds, loaded up and doing it again at the next stop. Everything was staged; even the arrival of the train was re-enacted for the cameras. Muskie read the same script at every stop.

Already weary, Chitty retreated to the open bars for press in one of the rail cars. “As I walk toward the rear through a deserted seating car, blocking the aisle is a 10 gallon galvanized tub filled with ice and four kinds of beer,” Chitty recalled. “In the adjacent seat sits this 30-something guy in shorts, Converse tennis shoes, a Guayabera shirt, safari hat, dark aviator sunglasses, pinching a long metal cigarette holder with cigarette. He’s looking up at me as I look down at his beer. After about 15 seconds of looks and silence, he breaks down and invites me to have a beer. I notice the press credential ‘Rolling Stone’ hanging from his neck. We hit it off. He had hash . . . I had Colombian pot.”

Hunter and Chitty were kindred spirits and although Chitty didn’t know Hunter’s work, seeing Rolling Stone on his press badge was a significant credential. Chitty played a supporting role in one of Hunter’s campaign adventures and eventually became his friend and neighbor for life.

The campaign allowed Hunter to show off his story-within-a-story style. His articles were about the agony of reporting and writing a story every two weeks and much of the folklore and language that would surround the character called Hunter Thompson (or the Uncle Duke caricature) came from this period, as Hunter constantly portrayed himself as a man tormented by deadlines lashing together a story, feeding twisted gibberish into the Mojo Wire under brutal deadlines, when he was at the mercy of savage and obscene editors on the other end of the line.

But his narrative device, in which getting the story became the story, fit perfectly his political reporting. It allowed him to present a scene then ask the questions readers asked. As he questioned his sources, readers were collaborators piecing together facts. Hunter presented himself as a manic and somewhat-inept reporter, a clever way to mask his shrewd style.

The episode with Monty Chitty, which appeared as “The Banshee Screams in Florida,” began with Hunter reading a story in the Miami Herald, learning he had apparently run amuck on the Sunshine Special and terrorized Senator Muskie and almost everyone else. He used the Herald story as an epigraph that hit him squarely between the eyes as he cut up grapefruit (with a machete, of course) for his room-service breakfast at the Royal Biscayne Hotel in Miami Beach.

So Hunter began the story at the end. He called some of his fellow reporters to figure out what had happened. He discovered the Muskie campaign had banned him for giving press credentials to a lunatic. Like a detective who knows the identity of a murderer but must find proof, Hunter worked backward, retracing his steps, figuring out how the mess had happened. It turned out that a thug identified on his press badge as Hunter Thompson of Rolling Stone had mercilessly heckled Muskie, pulling on the candidate’s pants legs at a campaign stop and shouting wild and obscene comments. After getting a reasonable account of the proceedings from his telephone source (in a conspiratorial note, he told his readers that his source’s name “need not be repeated here”), Hunter pieced together a chronology.

A couple of nights before, Hunter and Chitty had met Peter Sheridan, whom he dubbed the Savage Boohoo, in the lobby of a Ramada Inn in West Palm Beach. The Boohoo was drunk and angry, screaming gibberish, railing against Muskie to anyone who would listen. Normally, Hunter said, he would not have paid much attention to this sort of act, but the Boohoo had a special quality, “the Neal Cassady speed-booze-acid rap – a wild combination of menace, madness and genius.” The Boohoo’s behavior left Hunter with no choice but to invite him along for a ramble with Chitty. “Don’t mind if I do,” the Boohoo said in response to the invitation. “At this time of the night I’ll fuck around with just about anybody.”

Hunter, Chitty, and the Boohoo ended up spending five hours together. Again adopting a conspiratorial tone, Hunter declined to go into much detail: “I’d like to run this story all the way out here, but it’s deadline time again and the nuts & bolts people are starting to moan.” So he quickly wrapped up the story by confessing that when he heard the Boohoo’s sad tale of being trapped in West Palm Beach with no way to get to Miami, he had to intervene. He handed over his press pass for Ed Muskie’s Sunshine Special:

“It’s the presidential express – a straight shot into Miami and all the free booze you can drink. Why not? . . . [S]ince the train is leaving in two hours, well, maybe you should borrow this little orange press ticket, just until you get abroad.”

“I think you’re right,” he said.

“I am,” I replied. “And besides, I paid $30 for the goddamn thing and all it got me was a dozen beers and the dullest day of my life.”

He smiled, accepting the card. “Maybe I can put it to better use,” he said.

And, of course, the Boohoo could. Hunter’s closing line was worthy of O. Henry. At first look, the article seemed haphazard, but on subsequent readings artful. Much like Rashomon, the same story was told multiple times before a truth was revealed.

Thirty-five years later, Chitty recalled that the real ending of the story wasn’t quite so neat. There was a tacit agreement that Hunter would give Sheridan the credential, but he didn’t want to do it overtly. He left Sheridan in the hotel lobby in the wee hours, took the elevator up to his room, then sent his credential back to the lobby in the unoccupied elevator.

That was not the end of the story for Chitty. Three days later, back in his college apartment, Chitty was awakened by pounding on his door. Two faculty members and two fellow Alligator staff members were on his door step, telling him that the White House called the newsroom looking for him. A fellow member of the Alligator staff told him the White House had called, looking for him. “Of course, I believe they’re tripping on mushrooms,” Chitty said. He pulled on some clothes and, when he got to the Alligator office to talk to the White House assistant press secretary. Chitty was quick on his feet: “Yes, I met Hunter Thompson of the Rolling Stone magazine. No, that was not Hunter Thompson who boarded the hotel bus Saturday morning taking us back out to the train. Yes, I was with Hunter the entire night before, and I can only imagine this fellow lifted Hunters’ press credentials from his jacket that evening. No, that was not Hunter Thompson on the train that day. Yes, this fellow was threatening almost everyone with broken whiskey bottles. Yes, he was screaming lewd and profane language, grabbing every female by the ass aboard the train. No, it was not Hunter Thompson who grabbed Ed Muskies’ pants and attempted to pull him from the rear platform in the Miami train station during his final speech. I was standing ten feet away and can swear this fellow who went nuts was not Hunter Thompson.”

Nixon’s press secretary Ron Ziegler called Chitty again the next day to once again confirm the details. As Ziegler explained, Hunter’s White House press credentials hung in the balance. It would have been a crushing blow to his career as a political writer. “Both Hunter and I lied our asses off to the White House about Peter Sheridan,” Chitty recalled. Hunter was grateful, flying Chitty to Colorado to spend time at Owl Farm.

George Wallace, the segregationist candidate, was the winner in Florida, but Muskie still steamed ahead as the front runner until a Tuesday night in Milwaukee. The Wisconsin Primary was expected to provide the exclamation point for Muskie’s campaign. After a week of what he considered hellish exile in Milwaukee, Hunter contemplated life under President Muskie. Nixon was the anti-Christ, but even if Muskie could beat Nixon would he make any difference?

Just for fun, Hunter decided to use his Rolling Stone pulpit to spread a rumor about Muskie and his use of a “rare Brazilian drug” called Ibogaine. Even for a presidential candidate, Muskie had been acting a little weird. When conservative newspaper publisher William Loeb had criticized Jane Muskie, the candidate broke down in tears defending his wife. Hunter had also seen odd flashes of imperious temper as he watched Muskie deal with staff. Why not suggest that it was all the result of the candidate using a hallucinogenic drug?

“I never said that Muskie was taking Ibogaine,” Hunter wrote years later. “I said there was a rumor in Milwaukee that a strange Brazilian doctor had been showing up at his suite to administer heavy shots of some strange drug called Ibogaine. I never said it was true. I said there was a rumor to that effect. I made up the rumor…. I didn’t realize until about halfway through the campaign that people believed this stuff. I assumed that like the people I was around, and like myself, they were getting their primary coverage of the campaign from newspapers, television, radio – the traditional media.”

On Wenner’s orders, Hunter was stationed at Muskie headquarters the night of the Wisconsin primary and Crouse was at McGovern’s offices, to cover the candidate’s presumed concession speech. But when the numbers came in, a bizarre thing happened: McGovern won. After working nearly two years to build a significant political base in Wisconsin, McGovern scored his first victory of the 1972 campaign.

Wenner heard the returns on the network news and called Crouse immediately. “Don’t write a fucking word,” he told him. He then called Hunter and told him to go to the McGovern headquarters and file a story.

Instead, Hunter gathered several bottles of his usual supplies and went to sit with Crouse and coach him through his first major story for the magazine, a detailed and lucid analysis of how McGovern cleaned Muskie’s clock. Wenner had threatened to fire Crouse for disobeying his orders, but grudgingly admitted that he had another great reporter on his staff.

At that point in the campaign, after the Boohoo incident and the Ibogaine story, straighter members of the campaign press corps finally began to talk to the thug at the back of the bus. Thompson wrote all that great stuff in Rolling Stone that they wished they could write: that Ed Muskie “talked like a farmer with terminal cancer trying to borrow money on next year’s crop”; that Hubert Humphrey was “a treacherous, gutless old ward heeler,” who needed to be castrated, and that “getting assigned to cover Nixon [is] like being sentenced to six months in a Holiday Inn.”

“His caricatures were overstated,” said political reporter Curtis Wilkie, “but there was truth in them, especially in his portrayal of Muskie and his ferocious temper.”

“The brilliance of Hunter and his semi-hallucinogenic reporting was that it got to the truth about things,” said William Greider, who covered that campaign for the Washington Post. “You could read his account of Muskie, that he was on some strange Brazilian drug, and it spoke the truth about his odd behavior. He would describe these titanic struggles in the McGovern campaign, and maybe he was over the top, but the stories were true in a deeper sense. He was such a brilliant writer that he could leave you somewhat in doubt as to what he was actually describing (it may have been in his own head), yet nevertheless, it was wildly entertaining and on the money.”

“Reading Thompson obviously gave them a vicarious, Mittyesque thrill,” Crouse wrote. “Thompson had the freedom to describe the campaign as he actually experienced it: the crummy hotels, the tedium of the press bus, the calculated lies of the press secretaries, the agony of writing about the campaign when it seemed dull and meaningless, the hopeless fatigue.” As Wilkie said, “His work ethic was not the kind of thing any regular journalist practices. I don’t recall him taking copious notes, but he remembered things well.”

Now those reporters who had cold-shouldered him wanted to make nice, but Hunter did not suffer hypocrites gladly. He decided to hatch an elaborate revenge ploy and bring Tim Crouse into it. Study those other reporters, Hunter told him. “Watch those swine day and night,” he advised. “Every time they fuck someone who isn’t their wife, every time they pick their nose, every time they have their hand up their ass, you write it down. Get all of it. Then we’ll lay it on them in October.”

Crouse produced his next major Rolling Stone piece on the campaign press corps, which led to a book contract with Random House for The Boys on the Bus, published the following year. Again, Hunter’s instincts for what makes good books (Acid Test for Wolfe, Selling of the President for Joe McGinniss, and Boys on the Bus for Crouse) were acute.

For his part, Hunter did not want to be one of the boys on the bus. He was disgusted by the game. “Guys write down what a candidate says and report it when they know damn well he’s lying,” he told Newsweek. “Half the conversation on a press bus is about who lied to whom today, but nobody ever prints the fact that they’re goddamn liars.”

Crouse frequently visited Hunter in his unnatural habitat, the home-away-from home in Washington. “Sandy was an incredibly sweet person, devoted to what she saw as fostering Hunter’s genius,” Crouse said. She helped him develop his equilibrium each day he was home.”

As a novice writer, Crouse appreciated being the audience for Hunter at work:

I was in the guest room upstairs with him and saw how he would sit at the card table with a Selectric in front of him, his elbows out to the sides, sitting up very straight, and then he would get this sort of electric jolt and start to type. He’d type a sentence and then wait again with his arms out, and he would get another jolt and type another sentence. Watching him, I began to realize that what he was trying to do was to bypass leaded attitudes, received ideas, clichés, anything like that and go to something that had more to do with his unconscious and his immediate perception of things. He wanted to somehow get the sentence out before anything could interfere with it in the way of convention or preconception. The idea was that the story would function sort of like an internal-combustion engine, with a constant flow of explosions of more or less equal intensity all the way through.

Hunter became close friends with George McGovern’s campaign manager Gary Hart (later his senator from Colorado) and the campaign’s chief political adviser, Frank Mankiewicz. While in his dark period in Wisconsin, staying at a hotel he considered a shithouse, Hunter met attorney Bill Dixon, who helped mastermind McGovern’s primary victory. “Hunter showed up with a ten-foot long length of chain around him and an open drink,” Dixon said. “You knew who Hunter was immediately. He was the star of that campaign in the eyes of his fellow journalists.”

Frank Mankiewicz was the campaign veteran on the staff. He had run Bobby Kennedy’s doomed 1968 presidential run and despite his lofty principles, always reminded himself that politics was a game, an attitude Hunter admired.

Despite Hunter’s stories of massive drug-and-alcohol use and psychic ruptures under deadline pressure, Mankiewicz thought most of those stories were manufactured. “I always thought Hunter was sober and clean,” he said. “I assume there must have been episodes where he was wildly drunk or high, but I never saw it.”

Though of the same generation, Gary Hart approached Hunter with some caution. He liked him as a person, but was somewhat skeptical of his reporting and what it could do to help McGovern reach the coveted Youth Vote. “He brought the campaign to the attention of a certain sector of the audience, a lot of whom don’t vote,” Hart said. As campaign manager, Hart wanted the attention and endorsement of the New York Times, the Washington Post and all of the establishment papers. As much as he liked Hunter, he kept his work in perspective.

“He didn’t do journalism,” Hart said. “It was Hunter’s view of the world around him. That’s what made it so interesting and different. It required him to be in his own writing and he increasingly portrayed himself as wacko. When he would write about a political event, I couldn’t recognize it. Everything, even normal events, somehow had a back story that was unbelievable and over the top and bigger than life. Of course, that meant he had to be all those things.” Literary critic Morris Dickstein said Hunter’s stories were “wildly erratic yet [he] really gives the impression of having been there.”

Dixon said all the other reporters envied Hunter. “Reporters in those days couldn’t wait for Rolling Stone to come out to read what Hunter had written,” he said.

Mankiewicz said Hunter’s reporting was “the most accurate and the least factual” account of the 1972 campaign. Indeed, Hunter reported that at one point in the campaign, Mankiewicz leaped from behind a bush and tried to bash in Hunter’s head with a ball-peen hammer. Everyone knew that was a joke, right? Hunter thought he made it clear when he was going into flights of fancy. He wrote for his own amusement and if others came along for the ride, that was all right. Usually, he punctuated his fantasies with a line that was supposed to telegraph his fun to the masses: “Jesus, why do I write stuff like that?”

Dickstein again: “Hunter Thompson learned to approximate the effect of mind-blasting drugs in his prose style . . . . [And] in 1972 he affronted the taboos of political writing, and recorded the nuts and bolts of a presidential campaign with all the contempt and incredulity that other reporters must feel bit censor out. The result was the kind of straightforward, uninhibited intelligence that showed up the timidities and clichés that dominated the field. But in high gear Thompson paraded one of the few original prose styles of recent years, a style dependent almost deliriously on insult, vituperation, and stream of inventive to a degree unparalleled since Celine.”

Curtis Wilkie covered the campaign for the Wilmington News Journal in Delaware and met Hunter when one of his editors suggested that he seek him out and write a profile. They met around the time of the Wisconsin Primary and began a thirty-year friendship. As Wilkie calmly toiled to meet his daily deadlines, he noticed Hunter becoming frantic when he was on deadline. “His work habits were certainly different from mine,” Wilkie said. “Hunter lived by night and I’m a morning person. He showed up for things and did reporting, but much of what he was writing was impressionistic. His stories came to him in visions, not as the result of hard reporting.”

And his stories came to him in odd situations. When Iowa Senator Harold Hughes surprised McGovern by switching his endorsement to Muskie, Hunter tracked down McGovern as he was urinating, and got a candid statement of surprise and disappointment from him. “You never had a dull conversation with Hunter,” McGovern said.

“His work habits were as insane as he describes them,” said William Greider, a political reporter for the Washington Post. “He was extremely tense and serious and overwrought – and also very focused, in a way that only someone with that kind of an observer’s eye can imagine. He did drink a lot. He did do drugs a lot. That wasn’t imagined – maybe or maybe not exaggerated, but I doubt it. And yet he had a kind of earnestness as a reporter, which he sustained day after day in kind of excessive ways. You could never be quite totally sure – is he putting me on or is he putting himself on. I think it was probably a little bit of both. You have to be insanely sincere to behave the way he did and to write the way he did.”

Hunter knew he had to do things differently. “In Washington, truth is never told in daylight hours or across a desk,” he told writer Craig Vetter. “If you catch people when they’re tired or drunk or weak, you can usually get some answers.”

The frenzy of the spring ended and Hunter went West for the California primary. By this time, he was loose enough with McGovern and his staff to urge Hart to test-drive the new Vincent Black Shadow with him. (“It was as big as a small horse,” Hart remembered.) California marked the end of primary season and Hunter’s stomach turned as he watched McGovern shilling for votes. He was actively courting the old guard of the party, the same people who’d turned the police loose on the demonstrators in the streets of Chicago four years before. It was a political reality, but a personal betrayal.

“Thompson began to smell the fat cats latching on to the campaign,” Crouse wrote, and “had become wholly appalled at McGovern’s effort to woo the old party regulars.”

Primaries over, a long, hot summer and two political conventions, both in Miami, yawned before him. Washington was not home, though he enjoyed his new friends in politics. He amused them by zipping around town at 100 miles per hour and living up to the Hunter Thompson Legend, though in private he was the courtly Southern Gentleman that Virginia Thompson struggled to raise. Sally Quinn, the Washington Post reporter turned CBS News personality, remembered Hunter as a vulnerable, sweet and gentle person. “He was never anything but absolutely polite with me,” she said. “He was a gentleman. I always thought he was – vulnerable, sad, too.”

During that baking-hot summer and just by chance, Hunter was within a couple hundred feet of the biggest political story of the century. While the Democratic National Committee’s offices in the Watergate complex were being rifled by political burglars on June 17, 1972, Hunter was downstairs swimming laps in the pool and later enjoying a refreshing tequila at the outdoor bar. He had a knack for being in the right place at the right time.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was finally out in book form and the other political reporters bought the book and at campaign stops, sheepishly asked Hunter to autograph it for them. Suddenly, he was a celebrity on the bus.

“Hunter was beginning to be a cult figure,” Gary Hart said. “Other journalists followed him around like puppy dogs. It was like he had some magic that they wanted to capture.”

Ralph Steadman flew in from England because Wenner wanted to repeat the “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” magic. Steadman was miserable in the Miami heat, saying his hotel room was fit only for committing suicide. His attitude contributed to his art, as he created especially vicious portraits of the candidates: wheelchair-bound George Wallace spewing bile over an American flag; McGovern urging a convention hall full of lizards to “come home, America”; Nixon at the podium, farting through an ass that is Vice President Spiro Agnew; and the big boys of the press core all vomiting into their cocktails. The bitterness in Steadman’s drawings was reflected in Hunter’s prose, as he wrote off the possibilities of true political reform.

The egalitarian nature of the Democratic Party and its desire to be all-inclusive, left McGovern to address the nation with his acceptance speech at two in the morning. The Republicans, on the other hand, ran a slickly managed convention and President Nixon spoke to a prime-time audience and the chants of “four more years” were all heard before the late local news.

Hunter covered both conventions and tried to infiltrate a group of young Republicans heading into the convention hall to cheer Nixon. With his sporty attire and close cropped hair, he could pass as a conservative but for the McGovern button. He tried to rally some of the Nixon Youth to chant hateful slogans at the network television anchormen, in booths hovering over the convention floor. Unfortunately, he was outed by fellow journalist Ron Rosenbaum, who shouted his name when he saw him in the GOP throng.

Hunter felt a sense of doom about the Republican Convention. To him, the GOP convention chant of “four more years” had a master-race ring to it: Nixon Uber Alles.

Sandy delivered a son in Washington, and was surprised at how good the baby looked, considering all of her drinking. But then the child developed Hyaline Membrane Disease, the disease that had killed President Kennedy’s son Patrick in 1963.

“I didn’t hold him, but I looked at him,” Sandy said. The baby died after one day.

Sandy stayed in the hospital a couple of days to recover. She called Hunter when she was to be released. It was still morning, and he would be asleep. She told him not to worry, that she would take a cab. She wanted him to say, Of course I’ll come get you, but he didn’t.

After a season of Hunter’s relentless travel, the family was home at Owl Farm. But Hunter came home to crash, Sandy said, not to be her husband. He was also on the party circuit; he was a media star and everyone wanted him. The campaign kicked up again in earnest after Labor Day, and Hunter took Sandy and Juan on one of McGovern’s whistle-stop tours of the Great Plains, which proved to be good therapy. “It was the best thing,” she said. “He was very tender with me.” Getting back home was therapeutic – and she served as campaign manager that fall for a Democrat county commission candidate and made scores of the local phone calls that contributed to McGovern carrying Pitkin County, the only county in Colorado he won.

Hunter’s output slowed in the fall and his dispatches for Rolling Stone weren’t as frequent. On the Zoo Plane, the press plane following McGovern around the country, reporters got loaded on drink and drugs while accompanying the candidate to speeches in Des Moines, Sioux Falls, and Tacoma. Stuck with a bunch of sloppy drunks – something Hunter despised – he used his charm to woo some of the women aboard. He was not bold in his infidelity. One of his conquests said he approached her with a level of shyness she would expect in a high school sophomore.

Hunter spent the fall stalking McGovern’s campaign headquarters in Washington, looking for the villain who was killing the campaign. First, McGovern had taken on as running mate Senator Thomas Eagleton of Missouri, who did not tell McGovern about his history of mental illness and shock treatment. Embarrassed into removing him from the ballot – replacing him with Sargent Shriver, a junior-varsity Kennedy – McGovern never regained his momentum. As he continued to suck up to the party regulars, most of whom Hunter found loathsome, McGovern and his young idealists broke Hunter’s heart a little bit, day by day. McGovern was the best hope of his generation, the one man with a chance to take back his country from the greedy and the unprincipled. Finally, in a burst of rage, Hunter wrote the last article of his campaign coverage:

This may be the year when we finally come face to face with ourselves; finally just lay back and say it – that we are really just a nation of 220 million used car salesmen with all the money we need to buy guns, and no qualms about killing anybody else in the world who tries to make us uncomfortable.

The tragedy of all this is that George McGovern, for all his imprecise talk about “new politics” and “honesty in government,” is really one of the few men who’ve run for President of the United States in this century who really understands what a fantastic monument to all the best instincts of the human race this country might have been, if we could have kept it out of the hands of greedy little hustlers like Richard Nixon. McGovern made some stupid mistakes, but in contrast they seem almost frivolous compared to the things Richard Nixon does every day of his life, on purpose, as a matter of policy and a perfect expression of what he stands for. Jesus! Where will it end? How low do you have to stoop in this country to be President?

After the disappointing election and unhappy with All Things Wenner – particularly the editor’s niggling over expenses and Hunter’s being shuttled to the Zoo Plane for the last weeks of the campaign — Hunter resigned from the magazine. His alter ego, Raoul Duke, had been listed as sports editor on the masthead as well and Hunter demanded that both names be removed. This would not affect the upcoming campaign book, Hunter promised, but it opened the door for the more formal arrangement that he wanted: as a freelance writer with a contractual agreement with Rolling Stone. He did not want Wenner profiting on his image – though Wenner would not alter the names on the masthead.

Hunter took his family to Cozumel, Mexico, for a brief vacation to recover from the campaign and to fuel up for finishing the campaign book. For Christmas, Hunter got Juan a kitten and Sandy a mynah bird they named Edward. Hunter coached him to say, “Hi, I’m Edward. Birds can’t talk.” The important thing was being home. “It always felt good, going back,” Sandy said. “Always.”

The manuscript of his Fear and Loathing campaign book was due on January 1. Wrapped in bitterness and another nut-crunching deadline, Hunter was unable to work at home or in the Rolling Stone office on collecting his years-worth of campaign reporting into the book he’d promised Wenner. “I have a powerful aversion to working in offices,” Hunter admitted. “I am not an easy person to work with, in terms of deadlines.”

Wenner rented a suite for Hunter at the Seal Rock Inn, which advertised itself as “San Francisco’s Only Ocean-Front Motor Inn and Restaurant.” The suite had a small kitchen, which Wenner’s minions stocked with two cases of Mexican beer, four quarts of gin, a dozen grapefruit and “enough speed to alter the outcome of six Super Bowls.” Hunter carefully inventoried his supplies in the introduction of his book, another shot of gasoline on the fires of his image. As his editor, Alan Rinzler cracked the whip for two intense weeks; they were determined to beat The Making of the President 1972 to the book shelves.

It was mostly a matter of collecting the articles Hunter had written on the run and writing the connective tissue that would hold the book together. Here and there he had corrections to make, but mostly he was concerned with narrative flow. The collected pieces read as week-by-week journalism and he found himself early in the book, in February, making speculations about what would happen at the convention – which, of course, he already knew. But the book’s conceit, presenting the illusion of moment-by-moment coverage worked, conveying the hyper-rush of a presidential campaign witnessed on the run. He also employed the fake editor’s note device he’d invented back at Eglin Air Force Base. Since he hadn’t written much as the campaign wound down, he covered this section in a supposed transcribed dialogue between Hunter and Rinzler: “At this point, Dr. Thompson suffered a series of nervous seizures in his suite at the Seal Rock Inn. It became obvious . . . that the only way the book could be completed was by means of compulsory verbal composition.” The manufactured mayhem added to the book’s manic tone. “I would always say, ‘Let’s talk about the book,’” Rinzler said, “but he would disappear, hop in the car and go down to the local saloon.”

He missed his deadline, in part so he could include the Super Bowl in the book. He flew to Los Angeles for the January 14 game between Miami and Washington. He’d been leaning toward Washington, but once he heard that Nixon was for them and that the coach, George Allen, was televising prayer meetings with players, he decided that “any team with both God and Nixon on their side was fucked from the start.” The Super Bowl epilogue gave Hunter the elegiac device he needed to bring the story of the mad year home, in a cadence that owed much to Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms: “Around midnight, when the rain stopped, I put on my special Miami Beach nightshirt and walked several blocks down La Cienega Bouelvard to the Losers’ Club.”

By late February, the presses were rolling with the awkwardly titled Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72. Teddy White was left in the dust. With the prose smoothed out, the book gave a brilliant inside look at a presidential campaign. The decades haven’t dimmed the book’s relevance. It remains a full-scale portrait of the political process, one part of what Hunter called the American Dream, at work. “His book was just dead on,” Curtis Wilkie said. “It was very accurate.” Rinzler called it “his smartest book and his greatest intellectual accomplishment.” Hart enjoyed the book, but thought its political significance was overblown. “It wasn’t about the campaign,” he shrugged. “It was about Hunter.”

Despite – or because – of the Hunter-centric approach, the book had great influence. “It’s the moment we realized that traditional journalism is not sufficient,” said Carl Bernstein, who was uncovering the Watergate scandal for the Washington Post while Hunter was following the candidates around. “Hunter could not have existed in the mainstream press. The myth of objectivity is what holds us back the most.”

But the book was doomed. As a new publisher, Straight Arrow’s distribution was weak and most of the first printing was rejected by Wenner because Levison-McNally, the Reno printers hired to print the book, didn’t ink the pages sufficiently. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas had sold 18,000 copies in hardback and Wenner told Hunter he would be happy if Straight Arrow could push half that number of the Campaign Trail book.

But the Popular Library paperback of Fear and Loathing Las Vegas was taking off. The book was passed around the nation’s newsrooms and stuffed into college-campus backpacks. Hunter’s reputation grew with each battered paperback exchanging hands. It was a book devoured as much as read and the faithful committed passages to memory. Hunter’s people were paperback people. Eventually, the same thing happened with the Popular Library edition of the Campaign Trail book. By the time the Watergate scandal was in full eruption, Hunter was on his way to household-name status.

He was staying afloat. He had not written a best-seller, but he could be satisfied with his three books. He knew they were good and the critics generally liked them, despite huffing and puffing about his fast-and-loose attitude toward stenographic truth. Despite his critical success, he continued to exist the way he had for more than a decade: from job to job, from paycheck to paycheck. It was the lot of the freelance writer: Buy the ticket, take the ride.

And whether he wanted to be or not, he was famous.