The News in Black and White

Appeared in the Tampa Bay Times, December 17, 2006

Journalism is an odd business. Disaster, catastrophe and heartbreak make good news stories for those who practice this unusual craft. “Your worst day is our best day,” as journalist-turned-novelist Michael Connelly likes to say.

So it follows that the nation’s supreme tragedy – the systematic degradation of African-Americans – turns out to have been one the greatest stories ever told by the press.

The Race Beat, the saga of how the press reported the civil rights movement, is a long-overdue testament to the reporters who covered this domestic war story. Howell Raines, former executive editor of the New York Times, stepped into this territory three decades ago in My Soul Is Rested, an oral history of the civil rights movement. The section of his book devoted to journalists hinted at the rich stories these veteran reporters had to tell.

Yet their stories remained mostly unheard. The colors of memory faded. Some of the key reporters died. The press was too distracted by following the celebrity herd to look to the past for the story of its finest hour.

Finally, this epic is pulled together, and the stories could be in no better hands. Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff are respected journalists with experience on the civil rights beat, yet their book is not a venture into memoir. It uses the great-sweep historical approach to cover 60 years of American history that make anyone with a conscience cringe.

The authors avoid the pitfall of resorting to the great-man theory and turning this into another telling of Martin Luther King Jr.’s life. They recognize that the story has hundreds of heroes and even more villains.

Roberts and Klibanoff are wise enough to build much of the story around the experiences of the African-American press. The nation’s first black newspaper – Freedom’s Journal, founded in 1827 – was edited by two men that the Constitution denied rights as human beings but guaranteed rights as journalists. Throughout America’s separate-but-equal era of apartheid, journalists for such black-owned papers as the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier and the Baltimore Afro-American were telling an alternate history of the country, covering the stories the mainstream press ignored.

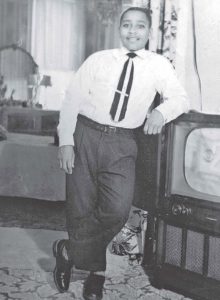

The 1955 torture and murder of Chicago teen Emmett Till during a visit to relatives in Money, Miss. – accounts differ, but apparently he spoke to a white woman – was the place where the black and white press crossed. To the black reporters, the Till trial, truly a mockery of justice, was part of a larger, continuing story. To the white reporters, it was an awakening, and soon, many of them had carved out a career covering the civil rights movement. White reporters learned a lot of lessons from reporters from black newspapers.

Starting with the Montgomery bus boycott, which used economic pressure to force the city to change its segregated public transportation policy, the story took on a stunning velocity. The boycott also catapulted the 26-year-old King to the front pages, giving the movement an identifiable superstar.

Student organizations staged marches and sit-ins at segregated lunch counters. Even within the movement, there was disagreement about how to achieve the goal of integration. The press reported the story with the same skill it would use to cover a military operation.

The spring of 1963 in Birmingham might have been King’s finest hour. He used schoolchildren as demonstrators, and when they were met with blasting firehoses and attack dogs set on them by the police commissioner, the resulting press coverage shocked the world. The stories and the pictures of children being abused by the authorities explained institutional racism as nothing had before.

King’s philosophy of nonviolent resistance played into one of the basic news values: conflict. When a nonviolent demonstrator was met with irrational, over-the-top violence from police, it made for a shocking story. King knew this and understood how to feed the news machine.

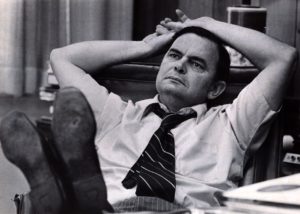

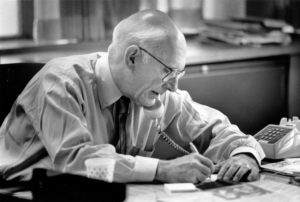

The Race Beat tells a compelling story, featuring portraits of great reporters such as John Popham, Claude Sitton and Roy Reed of the New York Times, as well as some of the major television reporters, including John Chancellor, Frank McGee and Richard Valeriani of NBC. Valeriani was clubbed with a baseball bat while covering the 1965 march in Selma, Ala., and delivered a TV report from his hospital room with his head heavily bandaged.

But Roberts and Klibanoff don’t focus only on the big-city reporters. They wisely fold in the story of the homegrown press. The civil rights story and the way it was covered by the national press forced the Southern press, which had helped maintain the segregated status quo, to take a hard look at itself and begin the long, painful process of change.