Brothers

From Everybody Had an Ocean: Music and Mayhem in Los Angeles (Chicago Review Press, 2017)

This is the preface to the book, about the first meeting between Dennis Wilson and Charles Manson.

. . . . . . . . . .

From the world of darkness

I did loose demons and devils

in the power of scorpions

to torment.

CHARLES MANSON

It was there in his face, loss and doubt behind hollow eyes. Once, he’d been unstoppable, one of the most successful young men of his generation. He was the reclusive king of California rock’n’roll, ruling from the background as a music industry was transformed around him and, in some ways, because of him. But at the key moment, when the whole world was watching, he abdicated and withdrew into his cocoon.

That was last year. Now, it had reached the point where Brian couldn’t let go of anything. He was intimidated, gun-shy, pathologically apprehensive, and much too afraid to let his songs out into the world, where they would be played and heard and judged by others.

No matter how great the songs, no matter how much everyone told him he was a genius, Brian Wilson was afraid of the criticism that came after he shared the music in his soul. So he kept adding superfluous fractions of melody to the recordings until he worked the musicians, and especially his brothers, up to a plateau of exhaustion and impatience. As long as we are all working, he thought, then we never have to finish. Thus was the state of Brian’s mental illness in the spring of 1968.

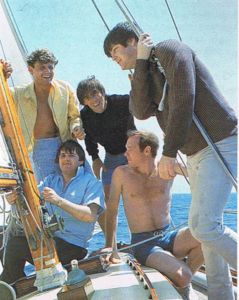

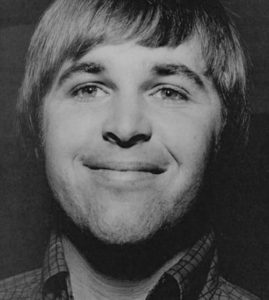

Difficult as it was now, in the middle of the night, and bleary at the end of a long recording session, Dennis Wilson still couldn’t help but admire his big brother. At that point in their history, the Wilson brothers (including younger brother Carl) had spent five golden years as America’s pre-eminent rock’n’roll band, The Beach Boys. They’d begun recording in 1962, when Carl was just fifteen and still in high school. Brian, nineteen then, was responsible for writing, producing and arranging all of the group’s recordings. It was a lot of responsibility for a guy who wasn’t yet old enough to vote.

The Wilson brothers came from modest beginnings in Hawthorne, California, cheek by jowl with Los Angeles, but, as they bragged in one of their hit songs, they’d “been all around this great big world.” Not bad for five boys from the suburbs.

Most rock’n’roll artists, up to that point, had been subject to the whims of Svengali-like record producers or music-business executives serving as masterminds behind the scenes, telling the young artists what to record, how to record it, and what musicians to use on the recording.

The Beach Boys were among the first to have its Svengali as a member of the band. Dennis once said of his older brother, “He’s everything. We’re nothing. We’re just his fucking messengers.” Those messages had sold millions of copies and made The Beach Boys famous. But now, detractors were stepping forward to knock the great Brian Wilson off his pedestal.

All evening and into the cracks of morning, Dennis had watched Brian, in his home studio, go through more than 20 takes of a new song called (for the moment) “Even Steven.” Instruments had been recorded the week before and the track had a vague sort of bossanova sound that would have been hot stuff ten years ago, but which seemed monstrously out of place in the uber-hip late spring of 1968.

The lyrical highlight of “Even Steven” was the verse in which Brian Wilson, once America’s most famous rock star of the decade, gave listeners directions to his house. In another verse, he sang of sharpening a pencil.

Dennis didn’t agree with it, but he understood where the criticism was coming from. The year before, after months of buildup in the press, Brian had decided not to release the experimental album he’d written and recorded for the group. Smile was full of odd and delightful musical ideas, but then arose that problem of his: the incessant tinkering, the fear of letting go, of giving the music to the world.

Brian had become monumentally nervous. When he was 19 and 20, churning out the band’s hits about surfing and hot rods, Brian was invincible. The hits kept on coming: “I Get Around,” “Fun Fun Fun,” “California Girls,” and a dozen others. He’d capped off that era in 1966 with the Pet Sounds album, a relatively somber meditation on lost love and aging, and then tied everything up with “Good Vibrations,” a number-one record that seemed at once as sweet and innocent as anything else in the Beach Boys’ candy-striped all-American canon, and, at the same time, very hip.

“Good Vibrations” was also when the not-letting-go began to be a problem. It took him six months and four recording studios to finish the record, and at the end of all that frustrating studio time, the finished record didn’t sound that much different from the first take.

“Good Vibrations” was such a wondrous, worldwide success that expectations were high for what was to be the follow-up album, a work to be called Smile. Brian referred to it as his “teenage symphony to God.” Magazine writers and admiring musicians made the pilgrimage to Brian’s home or to Western Recorders to see where the world of music was going next. New York Philharmonic maestro Leonard Bernstein put Brian on one of his television specials. Brian sat alone at a piano, playing an oblique, severely intellectual song called “Surf’s Up,” which, of course, had nothing to do with surfing:

A blind class aristocracy

Back through the opera glass you see

The pit and the pendulum drawn

Columnated ruins domino

But then, nothing. Brian couldn’t or wouldn’t finish Smile, so the other members of the group intervened to produce an album – long overdue under their contract with Capitol Records – made out of salvaged fragments and quickly recorded and innocuous ditties. Smiley Smile was lightweight, “a bunt instead of a grand slam,” as Carl Wilson so eloquently put it. Significantly, the credit “Produced by BRIAN WILSON” was replaced with “Produced by THE BEACH BOYS.”

In the dragging months he had tinkered with the album under relentless media scrutiny, Brian had been passed by. Before he could finish Smile to his satisfaction, his cross-Atlantic rivals, The Beatles, had released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The world anointed the British group as the undisputed heavyweight champs and the world soon forgot Brian Wilson. The Smiley Smile release was another nail in the coffin of Brian Wilson, Musical Visionary. He’s a fool, the critics said, thinking he can compete with The Beatles. Despite his gentle exterior, Brian was enormously competitive and the criticism stung.

What hurt worse was that some of the criticism came from within his group. His older cousin, Mike Love, was lead singer and often the lyricist for Brian’s lavish melodies. Mike liked the recipe that had worked so well a few years ago: benign songs about summer, cars, girls and young love. Mike had hated the turn Brian made with Pet Sounds. “Don’t fuck with the formula,” he told Brian during the vocal tracking for that album. Grudgingly, Mike recorded his parts, feeling vindicated when the album did not become a huge hit. Furthermore, Mike was irritated that Brian had gone outside the group and employed lyricists Tony Asher for Pet Sounds and wunderkind Van Dyke Parks for Smile. In addition to the rebuff, Mike knew he’d lose the significant songwriter royalties that boosted his income above others in the band.

A month after Pet Sounds, Capitol Records released a greatest-hits anthology called Best of the Beach Boys, which went to the top of the Billboard album charts. That’s what they want, Mike told Brian. But when “Good Vibrations” became a huge hit later that year, it was Brian’s season of vindication.

Then came the Smile catastrophe and now, a year after that ambitious project imploded, the group put out two pleasant but aggressively insignificant albums, Smiley Smile and Wild Honey. It was the era when each single or album from rock’n’roll heavyweights (The Beatles, Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones, The Byrds and, up to now, The Beach Boys) was supposed to be infused with great meaning and offer clues to deciphering the mystery of life.

Now, here was Brian, looking broken and confused, doing 22 takes of a song about sharpening a pencil.

Dennis and Carl were loyal to Brian, though they recognized he was losing what remained of his tenuous grip on reality. He’d turned the dining room of his Bel-Air mansion into a sandbox and moved his piano into the room, so he could wiggle his toes in the sand when he composed.

The living room was draped with canvas and stuffed with pillows, so he could have friends over to his Bedouin tent. That proved impractical because the fabric blocked the air conditioning vents, making the tent stifling.

Brian amused. Because he was deaf in one ear and not suited for travel, he had retired from touring with his group at the beginning of 1965. He promised to stay home, write songs and make records (using an immensely talented group of session musicians), while the remaining members of the group kept a rigorous concert schedule. When the group came off the road, Brian would steer them to the studio with a score of songs needing only to be finished with the Beach Boys’ lush harmonies.

Away from the group, at home or in the studio, Brian’s eccentricities multiplied. He went beyond amusing and fell into a chasm of paranoia. Marilyn, his patient young wife, could handle the sandbox, though she hated that the family cats shat there. She put up with the tent and the meetings held in the drained swimming pool. She even thought it was kind of funny when Brian refused to speak at a meeting with Capitol Records executives, instead playing recorded tape loops with such sayings as “That’s a great idea,” “No, let’s not do that,” or “I think we should think about that.”

But then he began to fear the outside world. He once bolted from a movie theater when one of the onscreen characters addressed a “Mister Wilson.” They’re after me, he thought. So he became a recluse, a rock’n’roll Howard Hughes. The other members of the group, which also included friends Alan Jardine and Bruce Johnston, were fine composers and singers in their own right. But they needed Brian for the extra touch of magic. He was the goose with the golden ear. “Jesus, that ear,” tough-to-please Bob Dylan once said. “He should donate it to The Smithsonian.”

So the group had built a recording studio in Brian’s Bel-Air home. It didn’t have the sonics of Gold Star or Western, where he had recorded the Beach Boys classics. It was small, with a well-worn beige sculptured carpet and a pink door with “Studio” spray painted on it in green in Brian’s balloonish script. Engineer Jim Lockert handled the nuts and bolts of building the mixing board and outfitting the room. It was homey and it would do, the group figured, since rock’n’roll was on a back-to-basics movement in the summer of 1968.

Young Marilyn gamely went along with having a recording studio directly below her bedroom. It meant constant traffic at odd hours, but it also meant that Brian, her lumbering beast of a husband, the tortured artist of rock’n’roll, had a reason to get out of bed. Work, she knew, might be his salvation. In the weeks since the carpenters had finished, though, she discovered that the studio’s existence did not always lure Brian from his room or out of his bathrobe.

But tonight, the studio held his attention. Marilyn heard the thumping of bass and drums from the room below, a monotonous unfurling of melody. So here they were, working on the song about sharpening a pencil, while Marilyn struggled through a fitful sleep upstairs.

During the golden days, no one questioned Brian or his judgments. If they did, they were immediately shot down.

“This sounds like shit, Brian,” Carl told his brother while recording “Little Honda” in 1964. Brian had instructed him to play a distorted guitar line to open the song. “Brian, I hate this.”

“Would you fucking do it?” Brian said. “Just do it.”

Later, Carl would tell this story as a way of saying he learned never to doubt his big brother. “When I heard it, I felt like an asshole,” he said. ”It sounded really hot.”

But that was on-top-of-the-world Brian, at twenty-one. Now he was an insecure frightened twenty-six-year-old.

Dennis still believed in him, but knew his brother’s issues would not be easily solved, which is why he was at the session, supporting him.

Dennis was not integral to the great harmonic blend of The Beach Boys. His voice was rougher, sometimes lurching toward off-key. When the performing group did “Their Hearts Were Full of Spring” onstage — a cappella, of course – Dennis sat behind his drum kit, silent, arms crossed. His presence was not urgent in the vocal tracking tonight, but he knew that Mike would try to work the room into some expression of disaffection with Brian and the scattered, unsure ways he labored these days in the studio. Dennis was there to support his big brother and help tamp down a rebellion, should one occur. It had been a quiet session, though, and now, discontent was yawning in the wee hours.

Brian had lived for years under pressure to make the records that lit up the radio. A lot of people depended on him: The Beach Boys, their families, their accountants and road managers. A lot of people needed Brian to write, produce and arrange two or three albums of material each year.

Don’t fuck with the formula.

But now his productivity had slipped and the pressure was doubled. At the home studio, at least he wasn’t tying up thousands of hours of expensive time at Gold Star or Western Recorders. The session musicians enjoyed working with Brian, but they were paid an hourly rate, so if he demanded unending takes of a song, or wasn’t sure how he really wanted to do the song, it became an onerous expense. At home, they had Jim Lockert as their on-call engineer, and they contracted with individual outside musicians on an as-needed basis.

Dennis and Carl both had grown up in Brian’s shadow. They had shared a room and, as the eldest, Brian was the natural leader, though he lacked Dennis’s sexual magnetism and Carl’s precocious diplomatic skills.

In childhood and adolescence, Brian had been particularly close with Carl and the two brothers and their parents spent hours harmonizing around the piano. Dennis, the extrovert, usually missed the family sessions in favor of hitching a ride to the ocean for a day of surfing. He was the handsome golden-boy athlete, the opposite of shy Brian and overweight and insecure Carl. But when Brian and Carl decided to start a musical group with their cousin Mike and a friend, it was Audree Wilson who told her sons they had to include the middle brother in the group. Thus did Dennis Wilson become the drummer of The Beach Boys. He did not take lessons and never became revered as a rock’n’roll drummer. But he pounded his drums with fury. He attacked them, the way he attacked everything in his life.

Hands down the best looking of the band, Dennis gave the group a sex appeal it sorely lacked. He also gave the group its identity. He was the only member of the group who actually surfed and he came up with the idea to write songs about surfing. He even supplied Brian with the language of the sport and the names of the best surfing spots up and down the coast. In one of their first hits, a Chuck Berry rewrite called “Surfin’ USA,” Brian name-checked some of the spots Dennis had mentioned:

At Haggerty’s and Swami’s, Pacific Palisades

San Onofre and Sunset, Redondo Beach, L.A.

Brian and the others ran with Dennis’s idea, even though it was false advertising. They weren’t surfers and Brian, the composer, was not the confident, strutting character embodied in his songs. They weren’t even the first artists to produce surf music. Guitarist Dick Dale, who recorded piercing instrumentals heavy on reverberation, had carved out that musical territory on the beach. But what Brian did with his songs and with his recordings with the group, was to take the music beyond the beach-rat subculture of Los Angeles and bring it to teen-agers in Des Moines, Columbus and Topeka. Kids in Omaha, taking The Beach Boys’ cue, strapped makeshift surfboards to the roofs of their old Impalas and pretended they were heading to the beach. “Surfin’ USA” even opened with Brian’s benevolent wish for his landlocked friends:

If everybody had an ocean across the USA

Then everybody’d be surfin’ like Californ-I-A

The Beach Boys were not a one-trick pony, despite their name (which was selected by a promotion man at their first record company). They did not confine themselves to surfing, but instead moved on to songs about cars, school, love and the joys of summertime. Again, it was Dennis Wilson who lived the life The Beach Boys sang about, but because his voice didn’t always fit in the harmonic blend, he was excluded.

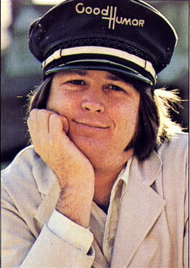

But now, as Brian’s star was beginning its descent to uncertainty, Dennis stepped forward.

For the new album, he’d written and produced two songs. Brian guided him through these maiden compositions, which were as idiosyncratic as anything Brian had ever written. Dennis inherited Brian’s fascination with celebrating small moments of joy (such as pencil sharpening). With “Little Bird,” Dennis exulted in the sensuality of nature, imagining that he had a bond with a bird he’d seen singing in a tree. Filled with strong images (“the trout in the shiny brook”) and arranged with chugging cellos, it was clearly a standout track. His other composition, “Be Still,” was a delicate lover’s prayer arranged for organ and voice. Dennis’s voice barely rose above a choked whisper, but the track was as deeply affecting as the more complex “Little Bird.”

Still – no way in hell would either of those songs become a concert sing-along like “Fun Fun Fun” or “California Girls.”

Brian was proud of Dennis’s accomplishments, but there was still much to do if they were to complete an album. Brian was still writing, but now needed help from Mike, Carl and Alan, as well as Bruce, who’d stepped into the group when Brian had quit touring. Brian was no longer the confident mastermind. Now the others held their breath in an unconscious effort to help get him through a session. He’d become so fragile.

“Again,” Brian said.

“Take 22,” Lockert said, and the tape rolled.

Though a lightweight confection, “Even Steven” was a window into Brian’s state of mind. This was his life: an unanswered phone call, sharpening a pencil, a lonely young man asking for someone to come visit.

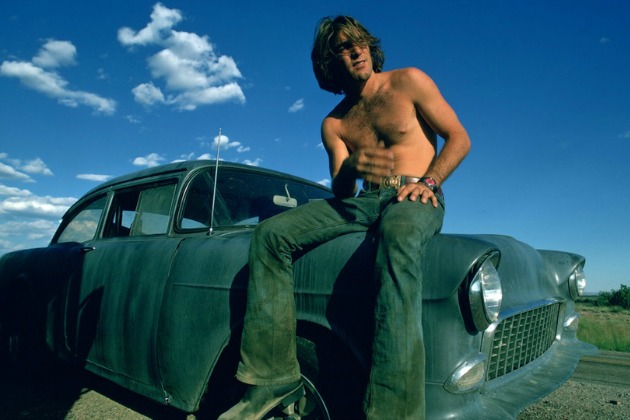

The session ended at three in the morning, not unusually late, but Dennis decided to go home rather than hit a club. It was a fifteen-minute winding drive down Sunset Boulevard between Dennis’s home and Brian’s studio, but in the middle of the night, in his Ferrari GTB, Dennis could easily make the drive in twelve.

Depressed and somewhat disturbed by the sight of his awkward and unsure big brother stumbling through a session, Dennis decided to seek respite in his usual manner. He’d spend the rest of the night sportfucking.

The other members of the band called Dennis “The Wood,” because he claimed he was always hard. Mike Love, the only real competitor for heartthrob in the group, was the front man who picked girls out of the audience and, unknown to the young women, signaled the road manager to make sure the prettiest ones got backstage. Despite a receding hairline and the inconvenience of marriage, Mike rarely had problems finding a woman for a one-nighter while on concert tour. He was handsome, looking much like actor James MacArthur, the young swain of Disney’s Swiss Family Robinson. Gifted with athletic stamina and, by all reports, a significant sexual organ, he gave Dennis a run for the money with the prettiest of the girls.

There was a natural and not entirely good-spirited rivalry between Mike and Dennis. Mike often saw himself as the leader of the band and, as commanding officer, looked upon Dennis as a surly buck private who was there only because of the insistence of his mother. And it also aggravated Mike when Dennis took the best-looking of the backstage girls to his room.

Dennis had his share of backstage girls and young starlets. He nightly pleasured himself at the trough of Hollywood’s most beautiful young actresses. He had been married and truly loved Carol, his wife, but he was addicted to sex. His love for Carol and for her two children, whom he had adopted, was genuine. But he had an addictive personality and could not stop doing the forbidden polka with other women, taking drugs, drinking booze and reveling in danger. He was reckless; his record of maimed cars spoke to that. He was fearless when he surfed. He seemed to live at only one speed: full throttle.

Carol had finally had enough of his serial adultery and moved out, filing divorce papers. Though they would always love each other, they could not live together.

So now Dennis was one of Southern California’s most eligible and sought-after bachelors. The record sales of The Beach Boys might have been in eclipse, but that didn’t make Dennis Wilson any less handsome or charming.

He’d leased an impressive estate befitting a good-looking rock star with voracious appetites, and he’d lost track of how many young women he’d brought back to the log-cabin mansion with its swimming pool in the shape of California. Humorist and film star Will Rogers had built the home back in the thirties as his hunting lodge, and though it had a Sunset Boulevard address, it was at the end of a long driveway, somewhat isolated by deep woods and adjacent to Will Rogers State Park. Here, Dennis could revel in his bacchanals with young women and they could luxuriate nude by the pool, hidden from prying eyes of neighbors.

Dennis figured that when he got home, those two girls would still be there. He’d seen them hitchhiking a few days before on the Pacific Coast Highway and stopped to pick them up. He showed off the silver Ferrari, bragged about being Dennis Wilson, laughed and joked and let them off at their destination. They said their names were Yellerstone and Patty.

Then he ran into them again, in the hours before the night’s recording session. They were hitchhiking on Sunset and Dennis pulled over when he recognized them. He had time before the session. Would you like to come back to my place for milk and cookies? This was no lame pick-up line; it was a genuine Dennis Wilson offer. The girls giggled. It’s raw milk, the only kind I drink. How could the girls resist?

He took them back to his home and showed off his gold records, the rustic mansion and the pool. Yellerstone and Patty liked Dennis but didn’t care too much about his celebrity or his music. The Beach Boys were already passé and not the kind of stuff they listened to. But Dennis was genuinely nice and deeply generous. He’d be a soft touch.

It was a beautiful, clear California day. Dennis slipped out of his clothes and the girls followed. He fucked both of them, then excused himself for the recording session.

I’ll be back late, he’d said. Make yourself at home.

They were both tall, with long hair parted down the middle. He was a rock star and had dated doe-eyed starlets and ingénues and though these girls didn’t have movie-star genes, they were attractive enough for what he wanted. He asked the polite questions but got only vague answers, oblique references to where they come from, their home now out in the desert and the man who ran their commune, a man they called The Wizard.

Yellerstone and Patty liked Dennis because he was handsome and athletic and friendly and solicitous. They were not beautiful and Dennis knew he could do much better. Hell, he’d always done much better. But these girls giggled, enjoying his jokes, fawning respectfully as if everything he said was some insight to Holy Writ.

They were willing. He was an addict and so he went after any fuck in a storm.

As he dressed for the session, Dennis noticed that the women were in no hurry to cover up. He liked that. Their bodies weren’t what he was used to either. They were both modestly built, thick through the middle, and not groomed like some of the starlets he’d dated. But he found a lot of those starlets to be tedious. He’d once had a date with actress Yvette Mimieux, but she was brittle and tiresome. He didn’t even try to fuck her. He left her at the door of her apartment with a thunderous explosion of gas in place of goodbye. He loved to tell that story.

Yellerstone and Patty were not beautiful, but they also didn’t come with the bullshit that came with show-business girls. Some of those types had dated him, he figured, because they thought it was good for their career to go out with a rock’n’roll drummer. These girls wouldn’t be like that. Hell, they’d be grateful.

He’d been doing 75 down Sunset and didn’t slow for the turn into his long driveway. As he drove up, he worried that the girls might have gotten bored and left. Instead, it looked like something was going on.

Dennis pulled up the lane and turned to park on the concrete driveway adjacent to the pool. The outside spotlights were on; he was certain he hadn’t turned them on before leaving. He looked to the house and saw that it glowed with electricity; he hadn’t left those lights on either.

He warily got out of the car. Judging from the noise, there was a hell of a party going on in his house. Through the windows, he could see a half dozen, maybe more, people in silhouette, and they all appeared to be girls.

He walked slowly toward the house, uncharacteristically nervous. He was a few yards from the back door when it opened and a man emerged. Dennis stopped, taken aback.

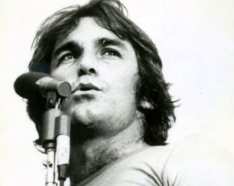

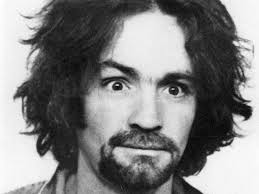

The man was short – a half-foot shorter than Dennis – with long hair to his shoulders and a patchy, unkempt beard. In the yellow glow of the porch light, Dennis could see that his clothes – a work shirt, blue jeans and moccasins — were well worn and filthy. He waved Dennis toward the house, toward his own house. The little man was acting as if he was lord of the manor.

Though he was small, to Dennis, the man looked menacing. Dennis stood still, but the man continued coming toward him, getting so close that Dennis took a step back. The craziness jellied in the man’s eyes frightened Dennis.

“Are you going to hurt me?” Dennis asked suddenly. He had no idea where that came from. It was unlike him to show fear.

“No, Brother,” the man said. He beamed, flashing yellowed teeth. “Do I look like I’m going to hurt you?”

Suddenly, the man dropped to his knees, leaned over, and kissed Dennis’s tennis shoes. When he stood up, the man again grinned at Dennis.

“Who are you?” Dennis asked.

“I’m a friend,” the man said.

Come on in, Brother, the man said. The women await.

The man’s smile was welcoming, though his eyes held menace. But as Dennis walked into his house, he saw that there were several nude young women walking around, comfortable and friendly in their nakedness. His stereo was turned up to maximum volume and was blasting Magical Mystery Tour, the latest album from The Beatles.

Dennis saw Yellerstone and Patty, who came to greet him like a long-lost friend. They tugged at his shirt, urging him to join them in what was minutes away from become an orgy. Patty unbuttoned Dennis and nodded toward the strange man. “This is the guy we were telling you about,” she said.

Dennis turned and looked at the man again, who smiled, baring his teeth.

“This is Charlie,” Patty said.

And that was how the friendship of Dennis Wilson and Charles Manson began.

Discographical note: “Even Steven” was retitled “Busy Doin’

Nothin’ ” and appeared on the Beach Boys album Friends, released June 24, 1968.