The Children’s Crusade

From the Orlando Sentinel, 1998

In 1955, when David Halberstam graduated from Harvard and contemplated a future in journalism, he took a detour before setting off for New York Timesland, the Pulitzer Prize and best-selling books.

With his degree and a term as Harvard Crimson editor, Halberstam could have picked from any number of jobs at big papers on the East Coast.

But he was too smart for that.

First he went to a small paper in the Deep South, and by 1960 had moved on to The Tennessean in Nashville.

The Tennessean was one of those papers apparently edited by a shovel. Strange and bizarre news items freckled every page. It was an editor’s nightmare and a writer’s dream, because writers got a lot of space at The Tennessean.

Soon Halberstam was off to New York Times glory. (So was another Tennessean writer, Tom Wicker. The Nashville newspaper was sort of a Triple-A farm team for the Times.)

But Halberstam left a little of his heart in Nashville. He went on to revolutionary Africa, a controversial stint as a Vietnam war correspondent (he was the guy President Kennedy tried so hard to get canned) and a long career as a best-seller machine. But he left behind perhaps his greatest story.

But Halberstam left a little of his heart in Nashville. He went on to revolutionary Africa, a controversial stint as a Vietnam war correspondent (he was the guy President Kennedy tried so hard to get canned) and a long career as a best-seller machine. But he left behind perhaps his greatest story.

Back in Nashville, this city boy from that effete elite college worked alongside homegrown photojournalists Jack Corn and Joe Rudis. Back at Harvard, no one taught Halberstam that the smartest thing a reporter can ever do is hook up with a great photographer. Halberstam did that on his own. With Corn and Rudis to do some of the ice-breaking hard work for this city boy in rural America, Halberstam was free to sit back and do his job: observe.

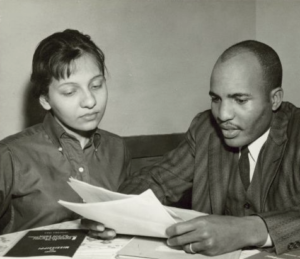

What he observed was one of the earliest successes of the civil rights movement. Under the guidance of James Lawson, an unheralded apostle of nonviolence, eight young students staged a series of sit-ins that led to the desegration of Nashville lunch counters. Sounds like a simple thing to us 40 years later. It was anything but.

Like any struggle, the victory was hard fought. But the eight students formed a bond that deeply affected the movement for the next several years. Among the eight were John Lewis, now a U.S. congressman, Marion Barry, Washington’s controversial mayor, and the husband-and-wife activist team of Diane Nash and James Bevel.

Halberstam has a place in the book, but does not step into the scene often. He gives us the story through the eyes of these participants, and readers have a new window through which to see the story of the social revolution.

In his recent Pillar of Fire, Taylor Branch included all of the same characters in his civil-rights history, but kept Martin Luther King as his focus. Most historians tend to do that.

But there were hundreds of activists engaged in the struggle and Halberstam succeeds in creating a gripping story of one small battle in an ongoing war.

And Halberstam knows it’s “gripping.” He likes words like “gripping” and sentences that go like this: “If there had ever been a more rural student arriving at an American college in the second half of the twentieth century than this young man determined to be a minister, who had practiced his spiritual calling by preaching to the chickens he was supposed to take care of on the small family farm in rural Alabama, it would be hard to imagine.”

Oh, David … still wordy after all these years.

But nobody reads David Halberstam books because of the beauty of the prose. We read them because he is a great reporter, and this may be his greatest story.