Talking Hunter

Appeared on “The Book Show,” Australian Public Radio, 2008

The host is Ramona Koval and the other guest is filmmaker Eva Orner.

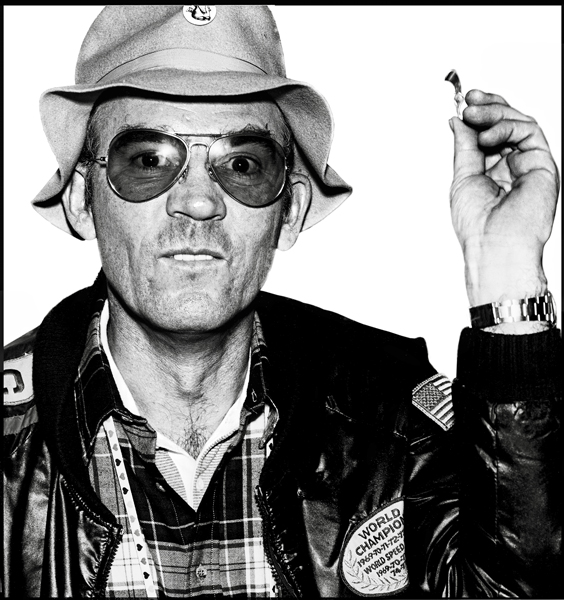

RAMONA KOVAL: There are some phrases and concepts that are forever enshrined in the mythos of a writer. For the iconoclastic Hunter S Thompson, it’s Gonzo journalism, freak power and fear and loathing.

Since his suicide in 2005, there have been many memoirs, many of them authored by his friends keeping the mythology of the cult writer alive. But when it comes to a subject as complex as Hunter S Thompson, there’s always room for more.

Adding to that legacy is Bill McKeen, a leading authority on pop culture and the author of what’s been described as the definitive Thompson biography, Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S Thompson.

And in Los Angeles we’re joined by Academy Award-winning Australian filmmaker Eva Orner, the producer of Gonzo, a new documentary on the life and work of Hunter S Thompson.

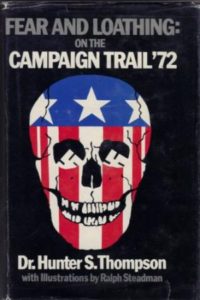

Bill McKeen and Eva Orner, welcome to “The Book Show.” In 1972 Thompson released what’s considered his most famous work, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream. Bill McKeen, what impact did that have at the time?

WILLIAM McKEEN: Well, I was a newspaper reporter then and I think all of us in the business suddenly had someone new to bow and scrape to. We just thought he was the most fantastic writer to ever work under the umbrella of journalism, and that kind of changed the way I think all journalism was practiced from that point. It was just such a different take on things, it was a monumental point of view, and as a book I put it in there with The Great Gatsby in that I think in American literature there are few books that can pass that test that you can read them and not want to change a single word.

RAMONA KOVAL: Eva Orner, you spoke to many people for the film who were influenced by Fear and Loathing which really cemented him as the inventor of Gonzo journalism. Who were they and what did they say about the effect it had?

EVA ORNER: Can I just say one thing before that, something that Bill just said that Hunter would have loved is the fact that he compared Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas to The Great Gatsby because that was one of Hunter’s favourite books and he in fact spent much of his early days retyping it by hand, which is how he said he learned to become such a great writer, just by following the flow and the rhythm of Fitzgerald’s work. So I think that was a great opening start to this conversation.

In terms of who’s in the film and who talks about Hunter and his influence, it’s so wide and so varied. When I think about that I think more about, obviously, friends and also people who were on the campaign trail with him in the early 70s on the book prior to Vegas. And obviously people like Johnny Depp had a huge life-changing experience spending time with Hunter and portraying him in the film.

RAMONA KOVAL: Let’s talk about some of the writing that you mentioned, Bill McKeen. You said he was a fantastic writer. What was it about the way he approached that work that was so different from how journalism had been done before?

WILLIAM McKEEN: Eva hit on something very important that I found out when I did an earlier book on Hunter back in the late 80s and that is that he taught himself to write by retyping the works of writers he admired, and I think that sounds insane, but what a great way to educate himself. He said he wanted to feel what it felt like to have those words pass through your system. I think that all that was a great exercise. He didn’t want to imitate them but he wanted to find his voice and I think he ended up having one of the most memorable voices in American literature. When I wrote that book…it came out in 1990, I put in the reference to him being the Mark Twain of our times and the editor took it out and, as you know, editors win. But when Hunter died, Tom Wolfe wrote an appreciation of him and called him ‘the Mark Twain of our times’, and everyone thought he was a genius. Well, I was there first.

RAMONA KOVAL: You were a genius first!

WILLIAM McKEEN: Yes, but I do think there’s an awful lot of Hunter that’s in the category of Mark Twain and of HL Mencken.

RAMONA KOVAL: Can we just focus right onto the words. What was it about his writing style that was so different from what had gone before? You said he had a way of turning a minor subplot involving him into an epic, that’s about the ebb and the flow of the piece as he was writing, but what about his language? What was it that was so shocking and so revealing about his style?

WILLIAM McKEEN: I don’t know that it was shocking but it was just he had a massive vocabulary, and I just think he was so attuned to the rhythm in the writing and the words and how they sounded, and it made sense when you think that he wrote with music blasting and he called the music his ‘fuel’. He thought of his writing as musical, and so it has a great rhythm and a structure to it. And he would read everything aloud before he would send it off because he wanted to hear how it sounded. So he was a great craftsman.

One of the things he’s known for, of course, is unfurling all of these wonderful invectives on people and his terrible insults, none of which I’m sure we can say on the radio. But the remarkable thing, after going through 50 years or so of his writing, he never really repeated himself. When it came to those sorts of build-ups of great crescendos or Wagnerian kinds of insults he’d throw at people, they were always different. I think the thing that I came away from this book feeling about his writing was that he was somebody who really enjoyed the act of writing when it was going well because there’s so much pleasure that comes out in his use of words.

EVA ORNER: I think also there was a huge amount of mischief that he found in his writing, and I so agree with everything that you’re saying, and I think also it was this mischievous, fun, kind of play that he had. And 40 years later…when you say his writing is unique and original, there’s no other voice like it. There are lots of people who have mimicked and come after, but when you read his stuff now…I’m 38 and I wasn’t aware of him when I was growing up until I was about 14, but you read his stuff now and it’s still shocking and just so original.

RAMONA KOVAL: And what shocks you, Eva, what is shocking about it?

EVA ORNER: Honestly, to me, that it’s so honest. I think because now obviously we’re all caught up in the crazy election campaign in America, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail written in ’72 is still the best campaign trail book ever written. It just cuts to the truth, and he did crazy things; he made things up, he spread rumours, and these things became part of the national media and people believed them and then they were reported in mainstream media. So he played with people and he had fun but he never pushed it too far. But he was this journalist who in a way was able to create some news and create stories.

EVA ORNER: Honestly, to me, that it’s so honest. I think because now obviously we’re all caught up in the crazy election campaign in America, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail written in ’72 is still the best campaign trail book ever written. It just cuts to the truth, and he did crazy things; he made things up, he spread rumours, and these things became part of the national media and people believed them and then they were reported in mainstream media. So he played with people and he had fun but he never pushed it too far. But he was this journalist who in a way was able to create some news and create stories.

RAMONA KOVAL: In fact he threw his support behind the Democratic nominee George McGovern. How influential do you think was his endorsement of McGovern?

EVA ORNER: I think he played a huge role because he was writing on the campaign trail for the Rolling Stone magazine. Jann Wenner, the editor, took a huge gamble with sending him up to be this political correspondent, which he was not, and he was writing these cult articles that everyone was reading and the mainstream press was following. And he also did the same thing with Jimmy Carter. Early on he endorsed Jimmy Carter for Rolling Stone articles, almost by chance, and he became a really pivotal player in the fact that Jimmy Carter became elected. I feel like now journalists are very proper and very careful and very cautious in this age of 24-hour news and the internet, and he was just this crazy Gonzo voice who…I think honestly he thought about the consequences of his actions after he did them.

RAMONA KOVAL: Bill McKeen, this idea of writing things that aren’t true in journalism, what’s your view of that and how did that function?

WILLIAM McKEEN: Well, the essential truth was there I think. I may have some issues with that, but when you think about what he did, he was writing about Hunter Thompson covering a campaign, so whatever he wrote about was his view of the world, so in a sense it was accurate. That’s how I’ll buy my way out of this.

RAMONA KOVAL: Why do you think you need to buy your way out of it, Bill?

WILLIAM McKEEN: I think because although journalists loved him and he was a great influence on a lot of journalists, he doesn’t pass the test to be a rank and file journalist in the classic sense of giving this guy equal weight to that guy. But he never wanted that anyway, so I don’t think that mattered to him. And I think we’ve all seen what kind of a mess the so-called objective press can get us into. You just have to look at Senator Joe McCarthy in the 1950s, you have to look at any other demagogue who knows how to use the media and you see that sometimes that whole concept of objectivity is kind of an inadequate notion, and it takes someone like Hunter Thompson to take society by the neck and say, ‘See what you’re doing here?’ and shaking us. With all the humour and joy and the great fun of Hunter’s writing, there was always a sense of outrage, and I think that’s the really thrilling thing about the Gonzo film is that…and this is the word I used to describe it when I saw it at the film festival, the audience was cheering and going ‘yeah!’ because we kind of miss that feeling. I think we’ve all been drinking Kool-Aid or we’re just comatose, we don’t pay attention the way we used to. That film really brings back the intensity of Hunter’s time and also his great emotional impact on the group of journalists from that generation.

RAMONA KOVAL: You mentioned drinking and we talked about fuel before. Eva, tell me about his legendary imbibing of everything.

EVA ORNER: I will say that when we started to make the film about Hunter…and I think when you do any project about Hunter the perception is it’s going to be sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll and a little crazy, and we were very, very careful and aware that we wanted to preserve and focus on his genius as a writer and his most prolific and successful years. But you can’t mention Hunter without talking about his legendary drinking and drug-taking. There are some wonderful stories that people like George McGovern tell. George McGovern is this wonderful southern senator and he was almost the president, and he tells stories about him and his wife going out to dinner with Hunter, and Hunter ordering six beers and four whiskeys and looking over and saying, ‘Well, you’d better take their order as well.’ It is true and it was legendary. It was amazing that he functioned the way that he did because everyone tells stories about him always, always drinking. And he talks about and often does it on film, imbibes various substances. So it’s no big surprise that he didn’t live to a ripe old age. In my mind it’s pretty amazing that he stayed in the shape that he did until he was about 60. And I think he corrupted people along the way, like Ralph Steadman his long-time illustrator and collaborator, and a bunch of people. I think they took on this Pied Piper-esque journey with him.

RAMONA KOVAL: Bill McKeen, Outlaw Journalist is your second book on Hunter S Thompson. The first one you said you wrote in 1991, which is more a study of his work than a look at his life. Tell us what he thought of your first book.

WILLIAM McKEEN: He wrote me a note that, again, I can’t quote on the air…

RAMONA KOVAL: I think you can quote. It’s okay, this is Australia, Bill, we can say words in context.

WILLIAM McKEEN: Oh you can? Well, he called me a shit-eating freak and said he was going to gouge my eyes out with spoons and urged me to learn Braille quickly, and of course I knew that meant he liked it.

The guy that was the cinematic Boswell who followed him around for 30 years, this filmmaker Wayne Ewing, who was very kind to me, told me that Hunter had kept that on his kitchen counter, one of the books that was readily at hand, and when he was depressed or when he’d gotten a bad review he’s ask Wayne to read aloud from it. I didn’t find that out until actually I was done with this book, and so I was very touched by that, to know that he appreciated it.

RAMONA KOVAL: And what made you write the second book?

WILLIAM McKEEN: It was my wife. When Hunter killed himself and all these people were calling to interview me because they had Googled academic work on Hunter Thompson and I came up, I kept talking about this wonderful writer, and the stories that were coming out in the press were all about this guy that was a clown who used drugs. And I thought, this is horrible, I hate to think of this fine writer, a great American literary figure being treated as a cartoon character. And my wife just said, ‘Honey, that’s your next book.’ And I said, ‘I already wrote one on him, I’m not going to do it again.’ But she was persistent and eventually I gave in, as I always do to her.

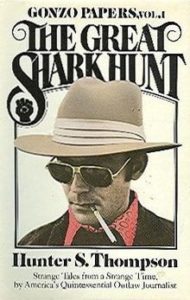

And I’m very glad I did it because I do feel that…of course Hunter did use drugs and he drank a lot, but so what? I think at a certain point those things get old and so many other people that write about him focus only on the craziness and the drug-taking and the alcoholism. And I just sort of say, for example, ‘in 1969 he began using mescaline’, which is sort of like saying, ‘at that point Rachael decided that broccoli wasn’t so bad’ and it just became part of the diet. I think that’s the good thing about the Gonzo film too is that it wisely focuses on the serious artist, which is what I wanted to do. I think we’re a double-barrelled assault on those who know Hunter Thompson only as being a clown. If you Google images of Hunter S Thompson you’ll get a lot of people wearing Halloween costumes, and I think he’s the favourite writer for a lot of people who don’t read. So I’m happy that this book and that film have brought attention to the more serious side of the work.

RAMONA KOVAL: Bill McKeen, I believe you actually tried to go Gonzo early on in your own writing career. How did you do?

WILLIAM McKEEN: I was very young, and I was under the influence of Hunter Thompson, it was about 1971 or 1972, and I decided I would go cover the Mr and Miss Nude America Pageant and do it Gonzo-style. When I came back to the newsroom and tried to write the story about the very disturbing event of going to the nudist colony…disturbing because I was only 18 years old and fairly innocent, I realised there was only one person in the world that could write like that, and that was a revelation to me. And even today 18-year-old students love Hunter Thompson, they want to write like him and I say, ‘Go ahead, try it,’ and then they fail and I say, ‘Well, only one person could write like him and only person can write like you.’ So I think his style just stands out. You could take one sentence out of something he wrote and see the DNA of Hunter Thompson in it.

RAMONA KOVAL: He was very courageous in his observation of what was really going on behind the scenes. He was pretty courageous by going deep into the Hell’s Angels territory really. I just wonder though whether…if you teach courage as a teacher of journalism, you might not have to involve substance abuse and getting very, very drunk and all the risks to your brain and all the risks to your health…can we teach courage without emulating the life?

WILLIAM McKEEN: I would hope so. Hunter himself said that famous statement ‘I don’t recommend drugs, alcohol and craziness to everyone but they work for me.’ I would be the opposite. I’m sort of cautioning students all the time about taking good care of themselves and not drinking and always being in control mentally and so on. That’s why I don’t want to have the focus be on his bad habits, I want them to be on the result of his life and work.

RAMONA KOVAL: Eva Orner, what happened to him after the 1970s? He continued to write, but what do you think…by the 80s, was his best work behind him?

EVA ORNER: That was definitely our feeling. I don’t want to pretend I’m a Hunter scholar, but I do feel like the best of his writing, Hell’s Angels, the two Fear and Loathing books, it was just this incredibly prolific time. And after that there was a bunch of books and there were definitely some great magazine articles that he did but it became a less and less prolific writing journey for him. We really skipped over the later part of his life for that reason because it just wasn’t the same fire and it felt almost like a bit of a caricature of Hunter was developing, and that happened with the Doonesbury character, the comic strip that was created about him, and he became more of a recluse. But what’s interesting is just shortly before he killed himself he wrote this incredibly moving piece…he was writing like a blog on ESPN’s website, and he wrote this incredible piece after 9/11 basically predicting what was going to happen and the craziness that was going to happen with George Bush and we started the film with that. I think that’s very powerful because it shows he still had a very relevant voice.

EVA ORNER: That was definitely our feeling. I don’t want to pretend I’m a Hunter scholar, but I do feel like the best of his writing, Hell’s Angels, the two Fear and Loathing books, it was just this incredibly prolific time. And after that there was a bunch of books and there were definitely some great magazine articles that he did but it became a less and less prolific writing journey for him. We really skipped over the later part of his life for that reason because it just wasn’t the same fire and it felt almost like a bit of a caricature of Hunter was developing, and that happened with the Doonesbury character, the comic strip that was created about him, and he became more of a recluse. But what’s interesting is just shortly before he killed himself he wrote this incredibly moving piece…he was writing like a blog on ESPN’s website, and he wrote this incredible piece after 9/11 basically predicting what was going to happen and the craziness that was going to happen with George Bush and we started the film with that. I think that’s very powerful because it shows he still had a very relevant voice.

Another thing that was amazing, just before we made the film there was a Vanity Fair article about a case he sort of adopted. There was a girl who was involved in a murder who was convicted, I think it was in Colorado, this woman called Lisl [Auman]. And he very quickly realized she was completely innocent and she was caught up in this crazy murder case and I think she got life in prison, and he started this “Free Lisl” campaign and she was ultimately let out of prison, and this was all spearheaded by him. It shows that even late into his life he was very much the pursuer of justice and he would stand up to things that he perceived as being wrong.

I think one of the things that makes the film so relevant now and that I’m so proud of is it’s almost a call to arms to people in the media today to say step up, tell the truth, find the truth, tell the story. His lifelong friend Jimmy Buffett says…when he reminisces he says, ‘You know, this is all fun and we’re all reminiscing about Hunter and laughing, but we really miss him and he could have wielded a pretty powerful sword against what’s going on America right now.’ So I feel like there’s just this hole, there’s this voice that’s no longer here that was part of the fabric of American media and society for such a long time.

And as our other guest says, it’s too easy to just bundle him up in this sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll image that clings very tightly to him.

RAMONA KOVAL: Eva Orner, what was available to you as a filmmaker of Hunter S Thompson on film?

EVA ORNER: We were so lucky. We were dealing directly with the Hunter S. Thompson estate and basically it was a warehouse that no one had had previous access to and it was just a thousand boxes of videotape and of photographs and manuscripts and things. So we had complete access to that. And he did a lot of television over the years and a lot of radio, so we had audio tapes. And he was a crazy collector and hoarder. He used to audio-record a lot of his conversations. So we had a ten-month period of a bunch of researchers going through everything meticulously, it was a really treasure-trove of material, we were incredibly lucky.

RAMONA KOVAL: Bill McKeen, why do you think he was such a documenter of his own life and his own views and his own telephone conversations?

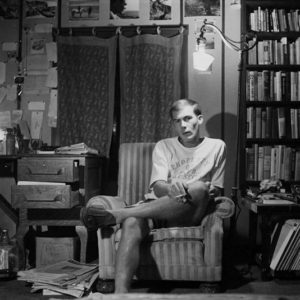

WILLIAM McKEEN: It’s funny you bring that up. It is strange that from the time he was 15 he kept a carbon copy of every letter. He would photograph the empty rooms where he lived, he would take pictures of where he worked, take a lot of self-portraits. He just had this unbelievable need to document himself.

His childhood friends that I got to know from the book, they all said he always knew that it was going to matter and that he was going to be famous. You were talking about the drop-off in his work, and I really think it was because he became famous, and I think fame is a terrible curse for a journalist because the first time he went somewhere, I think it was Watergate hearings, to cover it after all the Fear and Loathing stuff had come out, he couldn’t sit in the back of the room and cover the hearings because reporters were turning to him and asking for his autograph. I think that the real continental divide of his life was around that time when he stopped being a reporter and became more of a reactor in that he watched the news and then he would respond to it. So I don’t think it was a drop-off in quality as much as it was just a change in the way he looked at things.

Eva pointed out about that wonderful piece after the 9/11 attacks…I think one of the most brilliant things he ever wrote was in the last ten years of his life when he wrote the most brutal and hideous obituary for Richard Nixon you can imagine.

RAMONA KOVAL: Yes, he wasn’t a fan, was he.

WILLIAM McKEEN: No, but I think Nixon was, in a way, kind of his muse because he inspired Hunter to such levels of hatred that he was prolific.

RAMONA KOVAL: I think he said that Nixon could shake your hand and stab you in the back at the same time.

WILLIAM McKEEN: And he had a suggestion for the funeral…

RAMONA KOVAL: Yes, he said; ‘The casket should have been launched into one of those open sewage canals that empty into the ocean just south of Los Angeles. “He was a swine of a man and a jabbering dupe of a president.” He was an evil man, evil in a way that only those who believe in the physical reality of the Devil can understand.’

WILLIAM McKEEN: Isn’t that great?

EVA ORNER: Nobody can do that, nobody can imitate or replicate that language, it’s just so mellifluous and so gently mean.

WILLIAM McKEEN: No one has ever put the words ‘jabbering dupe’ together before, it’s perfect.

RAMONA KOVAL: Do you think he had a death wish? He used to ride his motorcycle at night without the lights on.

WILLIAM McKEEN: I do, yes. If you look back at the author’s notes to The Great Shark Hunt in 1979, it’s very clearly a suicide note.

RAMONA KOVAL: Yes, and you got the call late at night on February 20, 2005, that he had killed himself. Were you surprised and shocked or did you expect it?

WILLIAM McKEEN: I was, and looking back I don’t know why I was but I was. And the reporter asked me why and all I could think of was that he had a terminal disease and at that point I didn’t really realise how sick he was. I’d gotten a message from him a couple of weeks before but of course he didn’t leave his return number and so I just wrote him a letter back and I said ‘buddy, this works better when you give me the phone number, if you need anything just call me and let me know, but this time leave a number,’ and then I never heard back from him.

RAMONA KOVAL: Thank you both for being on “The Book Show” today.

WILLIAM McKEEN: Thank you.

EVA ORNER: Thank you so much.

RAMONA KOVAL: That’s William McKeen, author of Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S Thompson published by Aurum Press in the UK or Norton in the USA. And also Eva Orner producer of Gonzo: The Life and Work of Hunter S Thompson. And if you’re in Melbourne you can see at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image at Federation Square until Tuesday, November 4.

Broadcast 23 October 2008